Introduction: When Women Demanded to Be Seen

In 1989, the Guerrilla Girls plastered New York City with a provocative poster asking: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” Their research revealed a shocking truth: less than 5% of artists in the Modern Art sections were women, but 85% of the nudes were female. This single statistic exposed the glaring gender inequality that had plagued the art world for centuries.

The feminist art movement emerged in the late 1960s as a revolutionary force that fundamentally challenged who could be an artist, what subjects were considered worthy of artistic exploration, and how women’s experiences could reshape visual culture. These pioneering artists didn’t just create beautiful works—they dismantled institutional barriers, questioned patriarchal narratives, and proved that the personal is indeed political.

Today, the impact of feminist art resonates more powerfully than ever. From museum representation to market values, from #MeToo-era activism to intersectional perspectives, the artists you’ll discover in this comprehensive guide created ripples that became waves of lasting change.

In this article, you’ll explore:

- The historical origins and core philosophy of feminist art

- Revolutionary pioneers who launched the movement in the 1970s

- Artists who challenged institutional power structures

- Performance artists who reclaimed the female body

- Contemporary voices continuing the feminist art legacy

- The measurable impact on today’s art world

What Is the Feminist Art Movement? [Origins and Core Philosophy]

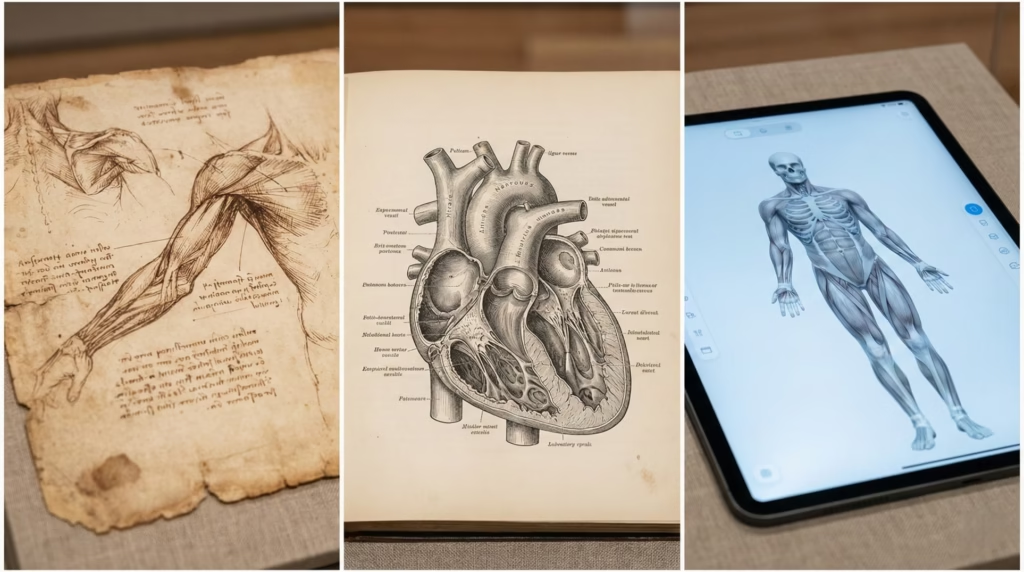

Historical Context: The Art World Before Feminism

Before the 1960s, the art world operated as an exclusive gentleman’s club. Women artists existed throughout history—from Artemisia Gentileschi to Berthe Morisot—but they were systematically marginalized, underpaid, and written out of art history textbooks. Major museums collected their work sparingly. Galleries refused to represent them seriously. Art critics dismissed their contributions as derivative or merely decorative.

The statistics were damning: in 1970, women comprised only 18% of artists shown in New York galleries despite representing nearly half of art school graduates. The Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection included works by fewer than 6% women artists. This wasn’t accidental—it was structural discrimination embedded in every institution.

Birth of the Movement (1960s-1970s)

The feminist art movement exploded onto the scene during the broader Women’s Liberation Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. As women marched for equal rights, reproductive freedom, and workplace equality, female artists recognized they faced similar battles in their professional lives.

The movement crystallized around several pivotal moments:

1970: Art critic and historian Linda Nochlin published her groundbreaking essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” She argued that the absence of celebrated women artists wasn’t due to lack of talent but systemic barriers—women were historically barred from life drawing classes, professional training, and institutional support that male artists took for granted.

1971: Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro founded the Feminist Art Program at CalArts in California, the first art program to examine art-making through a feminist lens.

1972: The creation of Womanhouse, an entire house transformed into feminist art installations, announced that women artists were claiming physical and conceptual space.

Key Principles and Goals

The feminist art movement wasn’t monolithic, but several core principles united its diverse practitioners:

Challenging the Male Gaze: Artists deconstructed how women had been objectified and sexualized throughout art history, creating alternative representations that centered female experiences and perspectives.

Reclaiming “Women’s Work”: Traditional crafts like quilting, embroidery, and ceramics—long dismissed as mere “craft” rather than fine art—were elevated to gallery spaces, challenging the artificial hierarchy between “high” and “low” art forms.

Making the Personal Political: Subjects previously considered too private or domestic for serious art—menstruation, childbirth, domestic labor, sexual violence—became powerful artistic material.

Institutional Critique: Artists demanded equal representation in museums, galleries, and art historical narratives while exposing systemic sexism through activism, protests, and alternative spaces.

Consciousness-Raising Through Art: Like the feminist practice of consciousness-raising groups, art became a tool for collective awakening about shared experiences of gender discrimination and patriarchal oppression.

The Personal is Political in Art

The feminist slogan “the personal is political” became foundational to the movement’s artistic practice. Women artists insisted that their individual experiences—of body autonomy, domestic labor, sexual harassment, or motherhood—weren’t merely personal complaints but reflections of systemic political issues.

This philosophy liberated female artists to explore subject matter that male-dominated art institutions had deemed unworthy. A painting about menstruation wasn’t just about biology; it challenged taboos and shame surrounding women’s bodies. A performance piece about domestic violence wasn’t merely autobiography; it exposed epidemic levels of violence against women that society preferred to ignore.

By centering women’s lived experiences, feminist artists expanded what could be considered legitimate artistic content and forced viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about gender inequality.

Revolutionary Beginnings: The 1970s Pioneers

Judy Chicago and “The Dinner Party” [Reclaiming Women’s History]

Credit: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/

No single artwork embodies the ambitions of 1970s feminist art more completely than Judy Chicago’s monumental installation “The Dinner Party” (1974-1979). This massive triangular table features 39 elaborate place settings, each honoring a significant woman from history or mythology—from Egyptian Pharaoh Hatshepsut to Georgia O’Keeffe.

Each place setting includes a hand-painted ceramic plate featuring butterfly and flower forms that abstractly reference female genitalia, challenging the pornographic male gaze by presenting female sexuality through women’s own artistic vision. The plates rest on intricately embroidered runners, reclaiming needlework as legitimate artistic practice.

The installation’s floor features the names of 999 additional women inscribed in gold, creating a comprehensive tribute to female achievement systematically erased from historical records. Chicago collaborated with over 400 volunteers over five years—itself a feminist statement about collective rather than individual artistic genius.

When “The Dinner Party” first exhibited, it sparked intense controversy. Critics called it vulgar, propagandistic, and crude. But over 100,000 people viewed it in San Francisco in 1979, with many women moved to tears seeing female history and bodies celebrated rather than objectified or ignored. The work demonstrated that feminist art could be ambitious, technically masterful, and emotionally powerful while remaining unapologetically political.

Today, “The Dinner Party” holds permanent residence at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art—evidence of how far the movement shifted institutional attitudes.

Miriam Schapiro and Womanhouse [Creating Feminist Spaces]

Miriam Schapiro co-founded the Feminist Art Program at CalArts with Judy Chicago, but her most influential contribution may be the Pattern and Decoration movement, which celebrated decorative traditions historically dismissed as feminine.

Schapiro coined the term “femmage” to describe her collage works incorporating fabric, buttons, rickrack, and other materials associated with women’s domestic craft traditions. Her “femmages” were bold, large-scale abstractions that demanded to be taken as seriously as any Jackson Pollock drip painting.

In 1972, Schapiro and Chicago led students in creating Womanhouse, transforming an abandoned Hollywood mansion into a labyrinth of feminist installations. Each room addressed aspects of women’s domestic experiences: a “Menstruation Bathroom” filled with feminine hygiene products, a “Bridal Staircase” where a mannequin bride appeared trapped in flowing fabric, a “Nurturant Kitchen” with breasts morphing into fried eggs on the walls.

Womanhouse announced that the domestic sphere—long used to confine women—could become radical artistic territory. Over 10,000 visitors experienced the installation during its month-long exhibition, proving tremendous public appetite for feminist art.

Faith Ringgold [Intersectional Feminist Narratives]

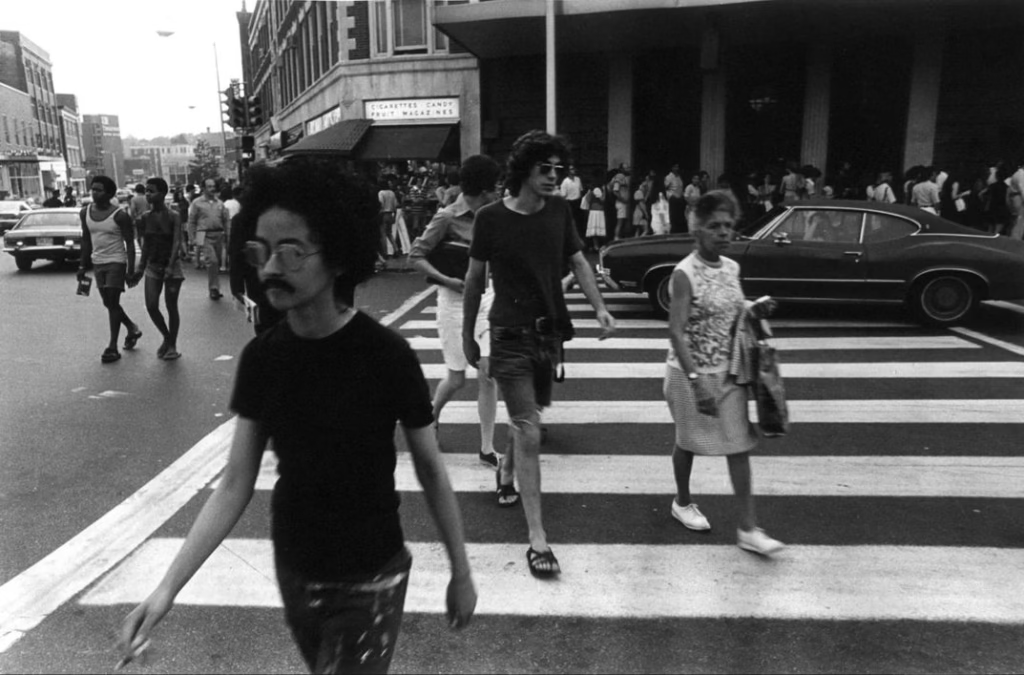

While white feminist artists received most early attention, Black feminist artists like Faith Ringgold pioneered intersectional approaches that examined how race and gender oppression intertwine.

Ringgold’s “American People Series” (1963-1967) addressed racial violence and civil rights struggles through powerful figurative paintings. Her groundbreaking political poster “United States of Attica” (1971-1972) protested the infamous prison uprising and massacre.

But Ringgold’s most celebrated works are her story quilts, which combine painting, quilted fabric, and written narrative. “Tar Beach” (1988) depicts a young Black girl’s dreams of flying above her Harlem rooftop, claiming freedom and possibility. The story quilt format was revolutionary—it merged fine art with craft traditions, visual imagery with literature, and African American quilting heritage with contemporary painting.

Ringgold also challenged exhibition discrimination by founding the advocacy group Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation. Her activism and art demonstrated that feminism without racial justice analysis remained incomplete.

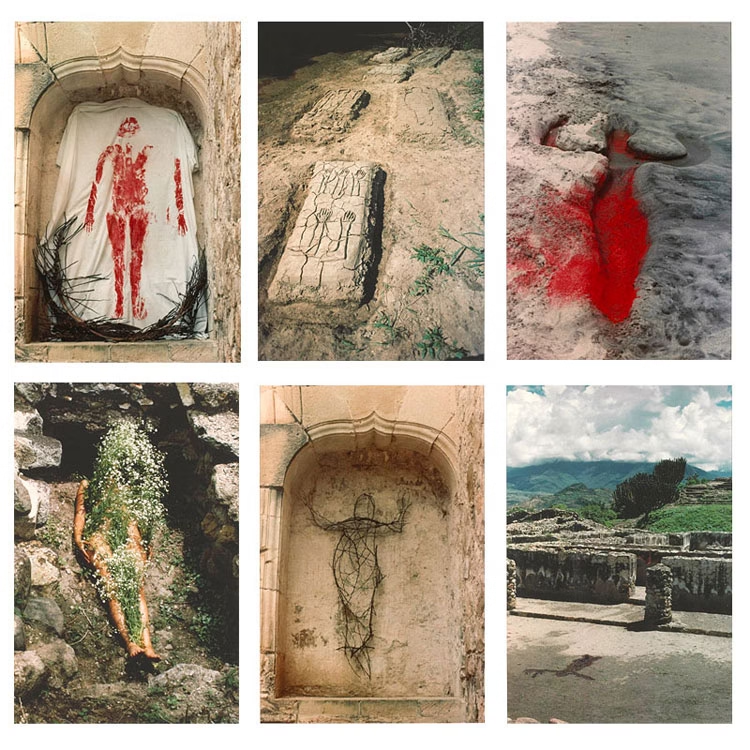

Ana Mendieta [Body and Earth as Feminist Territory]

Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta created some of the most visceral and poetic works in feminist art history before her tragic death at age 36 in 1985. Her “Silueta Series” (1973-1980) documented over 200 earth-body works where Mendieta’s body or its silhouette merged with natural landscapes.

credit: https://www.icaboston.org/

In these performances and photographs, Mendieta might cover herself with mud and flowers in a tomb-shaped depression, create her outline in gunpowder that exploded into flames, or carve her silhouette into earth and watch it slowly erode. The works powerfully addressed displacement (she arrived in the U.S. as a refugee at age 12), female body autonomy, spiritual connection to nature, and mortality.

Mendieta’s art resisted easy categorization—part performance, part sculpture, part photography, part ritual. She reclaimed the female body from centuries of objectification by male artists, presenting it instead as powerful, transformative, and fundamentally connected to earth and elemental forces.

Her early death in a fall from her 34th-floor apartment window—she was married to minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, who was tried but acquitted of her murder—made her a tragic symbol of violence against women. Today, feminist activists protest Andre’s exhibitions, chanting “Where is Ana Mendieta?”

Institutional Critique: Artists Who Challenged the System

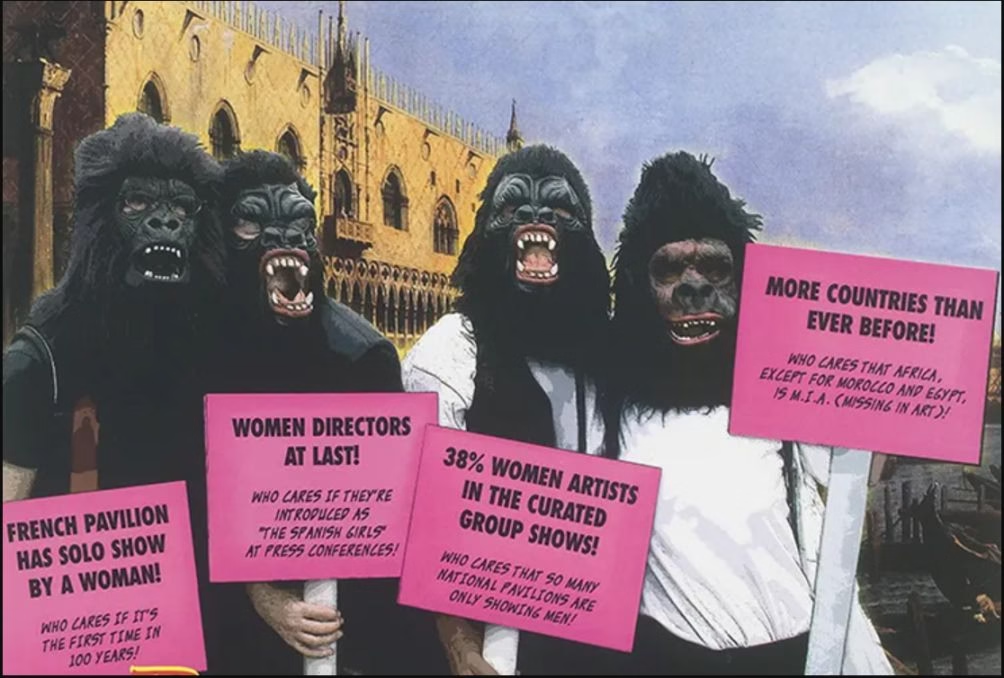

Guerrilla Girls [Anonymous Activism and Statistics]

Guerrilla Girls, Benvenuti alla biennale femminista! (from the series “Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: Portfolio 2”), 2005; Lithographic poster, 17 x 11 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay; © Guerrilla Girls, Courtesy guerrillagirls.com

In 1985, a group of anonymous women artists donning gorilla masks appeared in New York’s art world with a mission: expose gender and racial discrimination through irrefutable statistics and biting humor.

The Guerrilla Girls plastered the city with posters revealing uncomfortable truths:

- “These galleries show no more than 10% women artists or none at all”

- “The advantages of being a woman artist: Working without the pressure of success”

- “When racism & sexism are no longer fashionable, what will your art collection be worth?”

Their anonymity was strategic. By wearing gorilla masks and adopting pseudonyms of dead women artists (Käthe Kollwitz, Frida Kahlo), they prevented their critique from being dismissed as personal grievance while creating memorable, media-friendly imagery.

Their research methodology was simple but devastating: count. How many women artists had solo exhibitions at major museums? How much did museums pay for works by women versus men? The numbers revealed systemic discrimination that institutions could no longer deny or ignore.

The Guerrilla Girls demonstrated that feminist art activism could be witty, visually compelling, and data-driven. They inspired countless subsequent activist art collectives and proved that anonymous, collective action could achieve what individual artists could not.

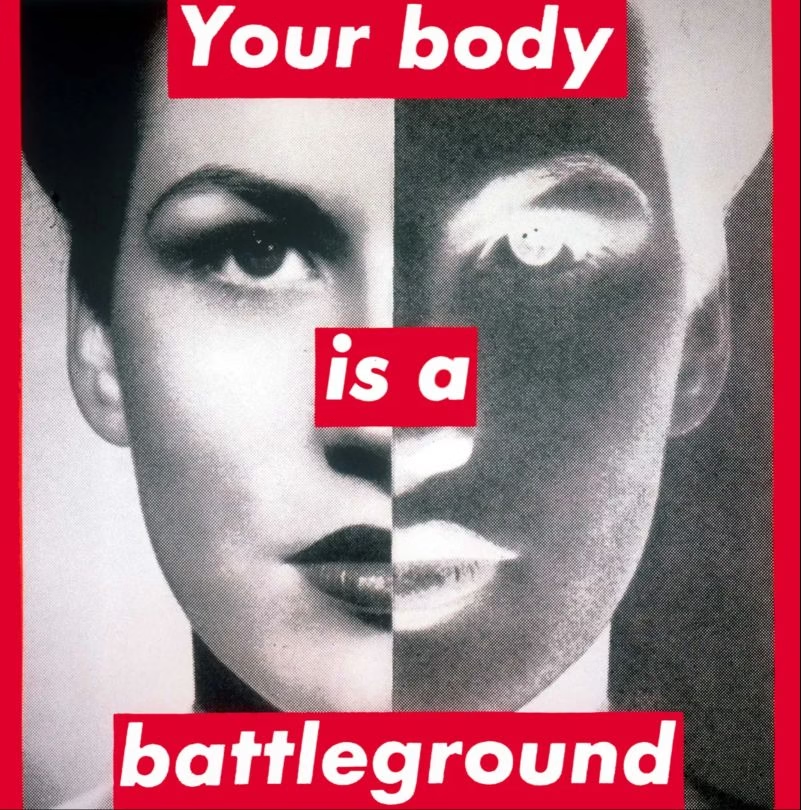

Barbara Kruger [Text as Feminist Weapon]

Barbara Kruger transformed advertising aesthetics into weapons of feminist critique. Her iconic works feature black-and-white photographs overlaid with bold white text in red boxes, mimicking commercial design to subvert consumerist and patriarchal messages.

Her most famous work, “Your Body is a Battleground” (1989), shows a woman’s face split between positive and negative photographic images with the titular text across her face. Created for the 1989 Women’s March on Washington defending reproductive rights, the work became an enduring symbol of body autonomy struggles.

Other works challenged power dynamics with phrases like:

- “Your gaze hits the side of my face”

- “I shop therefore I am”

- “We don’t need another hero”

- “You are not yourself”

Kruger’s genius lay in using mass media’s own visual language to critique how advertising, media, and consumer culture shape identity, objectify women, and naturalize power imbalances. Her works appeared not just in galleries but on billboards, bus shelters, and magazine spreads—infiltrating public space to reach audiences beyond the art world.

Jenny Holzer [Public Space Interventions]

Jenny Holzer pioneered using public space to deliver feminist messages through her “Truisms” series beginning in 1977. She pasted anonymous posters featuring single-sentence statements throughout Manhattan:

- “Abuse of power comes as no surprise”

- “Raise boys and girls the same way”

- “Protect me from what I want”

The statements ranged from darkly humorous to disturbing, forcing passersby to confront uncomfortable ideas in unexpected contexts. Holzer later projected her texts onto buildings using powerful LED technology, including the famous “Lustmord” (1993-1994) series about sexual violence, which she projected onto buildings throughout Europe.

Holzer’s work demonstrated that feminist art didn’t require imagery—language alone could confront, provoke, and transform public consciousness when strategically deployed.

Adrian Piper [Confronting Race and Gender]

Adrian Piper created some of the most confrontational and intellectually rigorous feminist art by centering how race and gender discrimination intersect in everyday life.

credit:https://www.genauturin.com/

Her conceptual performance series “Mythic Being” (1973-1975) saw Piper disguise herself with an afro wig, mustache, and men’s clothing to walk through Cambridge streets. She distributed photographic documentation in public venues, exploring how changing visible identity markers altered how strangers treated her.

credit:https://www.genauturin.com/

Piper’s “Calling Cards” (1986-1990) were small printed cards she would hand to people who made racist comments in her presence, reading: “Dear Friend, I am black. I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark.” The cards forced individuals to confront their racism while documenting the exhausting daily reality of microaggressions.

As both an artist and philosophy professor, Piper brought analytical rigor to exploring how social conditioning shapes perception and behavior regarding race and gender. Her work insisted that intersectional analysis—examining how multiple oppression systems interact—was essential to genuine feminist practice.

Performance and the Female Body

Marina Abramović [Endurance and Vulnerability]

credit: https://www.theguardian.com/

Serbian artist Marina Abramović pioneered using her own body as both medium and subject in extreme endurance performances that challenged boundaries between artist and audience, pain and transcendence, vulnerability and power.

In “Rhythm 0” (1974), Abramović stood motionless for six hours beside a table holding 72 objects ranging from a feather to a loaded gun. The audience could use any object on her body however they wished. Initially tentative, audience members grew increasingly aggressive—someone cut her clothes, another cut her neck, someone pointed the loaded gun at her head. When the performance ended and Abramović began moving, the audience fled, unable to confront what they’d done when she was objectified but suddenly uncomfortable facing her as a human subject.

The performance revealed disturbing truths about how objectification enables violence and how passive female bodies invite aggression. It remains one of the most profound demonstrations of feminist performance art’s power to expose gender dynamics through lived experience.

Other performances like “Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful” (1975)—where Abramović violently brushed her hair while repeating the title—critiqued expectations that women artists must conform to beauty standards.

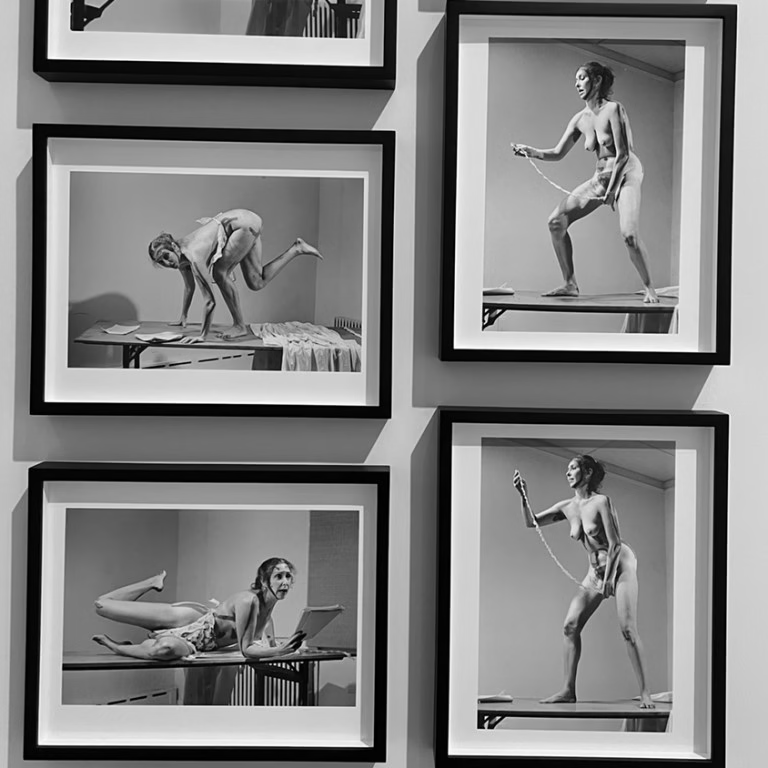

Carolee Schneemann [Breaking Taboos]

Carolee Schneemann shattered every taboo surrounding female sexuality and the body through groundbreaking performances that combined painting, dance, film, and ritual.

Her most infamous work, “Interior Scroll” (1975), saw Schneemann stand naked before an audience, painting her body while reading from a text scroll slowly extracted from her vagina. The performance confronted male critics who dismissed women’s art as too personal or body-focused by literally centering her body and feminine sexuality as sources of creative authority.

Credit: https://ricardopimentel.co.uk/

Earlier works like “Eye Body” (1963) featured Schneemann covering herself with paint, grease, plastic, and other materials in a series of transformative photographs. “Meat Joy” (1964), a group performance orgy with raw meat, celebrated sensuality and challenged bourgeois discomfort with bodily pleasure.

Schneemann insisted that female pleasure and sexuality could be subjects of serious art created from women’s own perspective rather than male fantasy. Her work was revolutionary for claiming that women’s bodies and desires belonged to women themselves.

Cindy Sherman [Deconstructing Female Representation]

Cindy Sherman has spent over four decades photographing herself in elaborate costumes and scenarios, yet her work isn’t self-portraiture—it’s systematic deconstruction of how visual culture represents women.

Her breakthrough “Untitled Film Stills” series (1977-1980) features Sherman posing as different female archetypes from 1950s-60s B-movies: the vulnerable ingénue, the sophisticated city woman, the isolated housewife. Each image feels familiar yet unsettling, exposing how cinema taught women narrow scripts for how to look and behave.

Later series grew increasingly grotesque and confrontational. Her “Centerfolds” (1981) were commissioned by Artforum magazine to create horizontal images but Sherman delivered vulnerable, uncomfortable images that resisted pornographic consumption. “Disgust Pictures” (1986-1990) featured Sherman with prosthetic body parts, vomit, and decay, deliberately rejecting beauty and attraction.

Sherman’s genius lies in using her own image to demonstrate that femininity itself is performance—a series of costumes, poses, and roles that women learn from visual culture. By revealing these representations as constructed rather than natural, Sherman empowered viewers to question and reject limiting gender scripts.

Contemporary Voices: Feminist Art in the 21st Century

Kara Walker [Confronting Racial and Sexual Violence]

Kara Walker emerged in the 1990s creating monumental black silhouettes depicting scenes from the antebellum South—but her imagery is far from nostalgic. Her installations show graphic depictions of slavery, rape, violence, and racist stereotypes in silhouettes that reference both genteel 18th-century portraiture and the racist visual propaganda of the Jim Crow era.

Walker’s controversial approach forces viewers to confront how racial and sexual violence against Black women specifically was foundational to American history. Works like “Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” (1994) use deliberately offensive language and imagery to prevent comfortable historical distance.

Credit: https://www.moma.org/

Her monumental “A Subtlety” (2014)—a 75-foot-tall sphinx with the face of a mammy figure made of 80 tons of sugar inside Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Factory—connected historical slavery to contemporary exploitation of Black labor. The work became a social media phenomenon as visitors took selfies with the sculpture, raising uncomfortable questions about how Black women’s bodies remain spectacle.

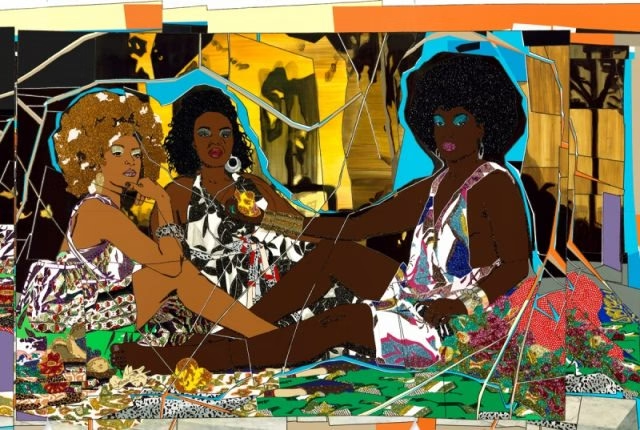

Mickalene Thomas [Reimagining Black Female Beauty]

Mickalene Thomas creates vibrant, large-scale portraits of Black women using rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel that challenge both European beauty standards and how Black femininity has been represented in art history.

Thomas’s subjects recline in confident, powerful poses referencing canonical paintings like Édouard Manet’s “Olympia”—but Thomas replaces the white prostitute with Black women who meet the viewer’s gaze with unmistakable authority. Her glittering surfaces force viewers to look closely and long, granting these women the sustained attention historically reserved for white subjects.

Works like “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires” (2010) reimagine Impressionist paintings with all-Black female subjects, asking: What if Black women had always been centered in Western art history? Thomas doesn’t just critique representation—she creates the alternative visual canon that should have existed all along.

The #MeToo Era and New Feminist Art

The #MeToo movement that erupted in 2017 catalyzed renewed feminist artistic activism. Artists responded to revelations about pervasive sexual harassment and assault with works processing trauma, demanding accountability, and imagining survivor solidarity.

Emma Sulkowicz’s “Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight)” (2014-2015)—where she carried her dorm mattress everywhere on Columbia’s campus to protest the university’s mishandling of her rape report—became iconic for #MeToo-era feminist performance.

Nan Goldin transformed her own experiences with opioid addiction into activism through P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), staging protests in museums that accepted funding from the Sackler family. Her work connected feminist body autonomy to corporate exploitation.

These contemporary artists demonstrate that feminist art activism remains urgent for addressing ongoing systemic violence and inequality.

Intersectional Feminism in Contemporary Practice

ContemDiverse group of contemporary women artists of different ethnicities in a modern gallery space, working on various art forms: digital art on tablets, traditional painting, textile work, and sculpture. Natural lighting, inclusive representation, collaborative energy. Modern, bright, professional art studio setting with colorful artworks in progressporary feminist art increasingly centers intersectional analysis recognizing that race, class, sexuality, disability, and nationality shape how individuals experience gender oppression.

Artists like Zanele Muholi document South Africa’s Black LGBTQ+ community, creating visual archives that celebrate Black queer existence against endemic violence. Tejal Shah explores how South Asian transgender and gender non-conforming individuals navigate identity. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith brings Indigenous feminist perspectives challenging both historical colonization and contemporary environmental destruction.

This intersectional turn represents the movement’s maturation—acknowledging that early feminist art often centered white, middle-class, cisgender women’s experiences while marginalizing women of color, working-class women, and LGBTQ+ individuals.

The Lasting Impact: How Feminist Art Changed Everything

Museum Representation Today (With Real Numbers)

The feminist art movement’s impact on institutional representation is measurable and significant—though the fight continues.

Progress Made:

- Women now comprise approximately 35% of artists in major museum collections (up from 5-7% in 1970)

- Museums have created dedicated spaces like the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art (2007)

- Major retrospectives of feminist pioneers now regularly occur at top institutions

- Art history curricula now include feminist artists and theory

Ongoing Inequality:

- Women still receive only 11% of museum acquisitions budgets at major institutions

- Women of color remain drastically underrepresented at approximately 5% of museum collections

- The Whitney Biennial 2019 featured 75 artists—only 53% women despite decades of feminist advocacy

- Galleries report that works by women sell for 47.6% less than equivalent works by men

These numbers reveal both tremendous progress and persistent structural inequality requiring continued feminist activism.

Market Value and Recognition

Feminist art’s market value has skyrocketed, though often after artists’ lifetimes. Ana Mendieta’s works now sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Joan Mitchell’s paintings have exceeded $10 million at auction. Yayoi Kusama became the highest-paid living woman artist.

Yet persistent gender pay gaps remain: a 2019 study found that works by women artists resell for 42% less than works by men, even controlling for factors like medium, size, and the artist’s exhibition history.

Education and Art History Curriculum Changes

Feminist art fundamentally transformed how art history is taught. Linda Nochlin’s question “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” is now standard curriculum. Feminist art theory—including concepts like the male gaze, intersectionality, and body politics—provides essential analytical tools.

Art schools now offer feminist art courses as standard rather than radical departures. Student bodies have shifted from predominantly male to majority female in most fine arts programs.

Influence on Contemporary Artists Across Genders

Perhaps feminist art’s greatest success is that its insights now influence artists of all genders. Male artists increasingly examine masculinity critically, explore vulnerability, and challenge patriarchal systems. Non-binary and gender-nonconforming artists expand feminist analysis beyond binary frameworks.

Contemporary art broadly reflects feminist principles: questioning who has institutional access, whose stories get told, how power operates through representation, and how art can promote social justice rather than merely reflect existing hierarchies.

Frequently Asked Questions About Feminist Art

Who Started the Feminist Art Movement?

The feminist art movement emerged from collective action rather than a single founder, but several key figures launched foundational initiatives. Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro established the first Feminist Art Program at CalArts in 1971. Art historian Linda Nochlin provided crucial theoretical foundations with her 1971 essay questioning why art history excluded women. Early activist groups like Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) and later the Guerrilla Girls organized collective protests demanding institutional change.

What Are the Main Themes in Feminist Art?

Feminist art explores several interconnected themes:

- Body autonomy and representation: Reclaiming how female bodies are depicted

- Personal as political: Making private experiences visible as shared political issues

- Institutional critique: Challenging museums, galleries, and art history’s exclusion of women

- Intersectionality: Examining how gender oppression intersects with race, class, sexuality

- Craft and tradition: Elevating “women’s work” like quilting and embroidery to fine art status

- Violence against women: Addressing sexual assault, domestic violence, and systemic abuse

- Identity and performance: Exploring how gender itself is socially constructed

Is Feminist Art Still Relevant Today?

Absolutely. While progress has been made, gender inequality persists throughout the art world. Women artists still earn significantly less, receive fewer gallery exhibitions, and occupy less museum wall space than male peers. The #MeToo movement revealed ongoing sexual harassment and assault throughout creative industries.

Contemporary feminist artists address current issues including reproductive rights rollbacks, trans rights, climate justice from feminist perspectives, and how technology shapes body image and gender expectations. The movement’s intersectional turn ensures it remains vital for addressing race, sexuality, class, and disability alongside gender.

How Did Feminist Art Change the Art World?

Feminist art fundamentally transformed institutional practices, artistic content, and theoretical frameworks:

Institutional Changes: Museums now actively collect women artists, host feminist exhibitions, and employ more women in curatorial leadership roles.

Expanded Subject Matter: Topics once considered too personal or domestic—menstruation, childbirth, domestic labor, sexual violence—are now recognized as legitimate artistic content.

Theoretical Frameworks: Concepts like the male gaze, intersectionality, and body politics now provide standard analytical tools throughout art criticism and history.

Medium Hierarchies: Traditional craft techniques are now exhibited alongside painting and sculpture, challenging arbitrary distinctions between “fine art” and “craft.”

Artistic Careers: Women now comprise majority of art school graduates and have sustained professional careers previously denied them.

Can Men Create Feminist Art?

This question generates ongoing debate within feminist art circles. Most argue that men can create art informed by feminist principles—challenging patriarchy, examining masculine socialization, supporting gender equality—but shouldn’t claim the identity “feminist artist” because they haven’t lived experiences of gendered oppression that inform the movement.

Male artists can be allies by: examining their own complicity in patriarchal systems, amplifying women artists’ voices rather than speaking for them, and critically exploring masculinity and male privilege. Artists like Robert Mapplethorpe (challenging masculine sexuality norms) and Andy Warhol (elevating traditionally feminine subjects) created work aligned with feminist goals without claiming feminist identity.

The key distinction: feminist art emerges from lived experiences of navigating the world as women, non-binary individuals, or people marginalized by gender systems. Men can support and learn from feminist art without appropriating its identity.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Revolution

The feminist art movement didn’t end in the 1980s—it evolved, deepened, and continues reshaping how we understand art, identity, and social justice. From Judy Chicago’s ambitious installations reclaiming women’s history to Kara Walker’s confrontational examinations of racial and sexual violence, feminist artists expanded what art can do, who can create it, and whose stories deserve telling.

These revolutionary artists proved that art isn’t politically neutral—it either challenges or reinforces existing power structures. They demonstrated that museums, galleries, and art history actively shaped gender inequality through their choices about who to exhibit, collect, and canonize. Most importantly, they insisted that women’s experiences, perspectives, and creative visions matter.

Today’s art world bears unmistakable marks of feminist art’s influence. Museums actively pursue gender equity in acquisitions and exhibitions. Art schools teach feminist theory alongside traditional techniques. Artists of all genders explore identity, body politics, and social justice issues feminist artists pioneered.

Yet the revolution remains incomplete. Women artists—especially women of color—still face institutional barriers, market discrimination, and cultural dismissal. The fight for genuine equality continues.

Support the ongoing feminist art revolution:

- Visit exhibitions featuring women artists at local museums and galleries

- Purchase works by contemporary women artists when financially possible

- Educate yourself about feminist art history and theory

- Advocate for equity in arts institutions through activism and donations

- Amplify women artists’ voices on social media and in your communities

- Challenge sexist attitudes and discrimination wherever you encounter them

The artists profiled here didn’t just create beautiful or provocative works—they fundamentally reimagined what art could be and who it could serve. Their legacy challenges each of us to continue that revolutionary work.

Last Updated: October 2025 | Researched and written with commitment to historical accuracy and inclusive representation