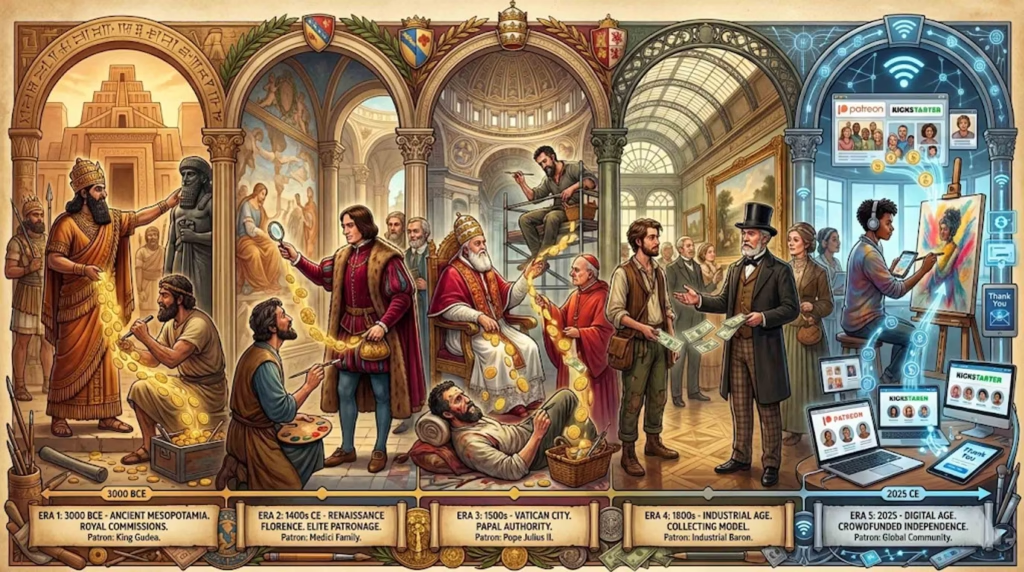

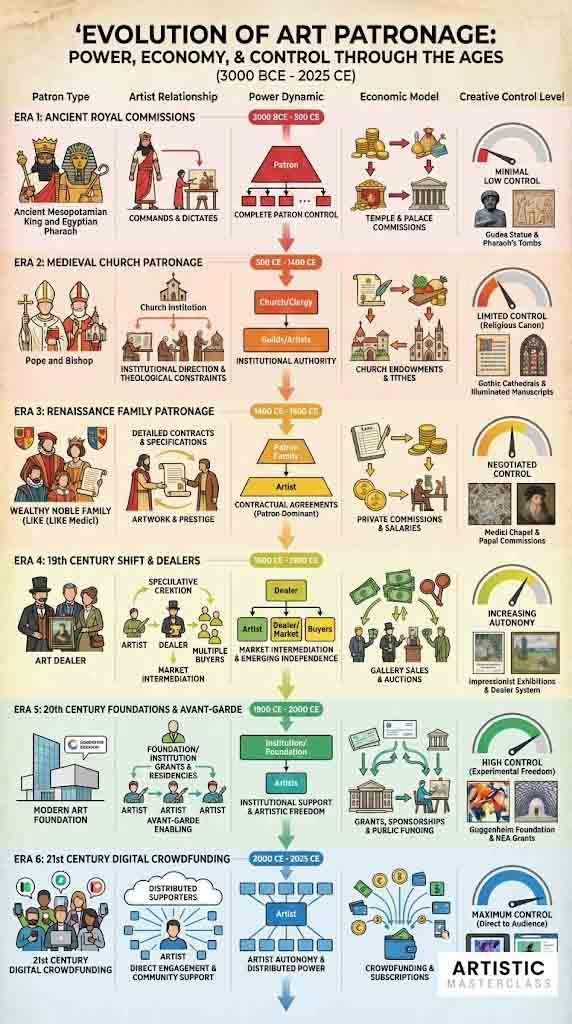

Behind nearly every artistic masterpiece in human history stands a wealthy patron—a king, pope, merchant, or industrialist who provided the funds, materials, and protection that made creation possible. From the diorite statues of ancient Mesopotamian ruler Gudea to Jackson Pollock’s revolutionary drip paintings, art patronage has shaped not just what art gets made, but who gets to make it and what it means.

This comprehensive guide traces over 4,000 years of art patronage across civilizations, examining how the relationship between money and creativity has evolved from ancient temple commissions to modern crowdfunding. You’ll discover the mechanics of patronage relationships, meet history’s most influential art patrons, and understand how power, propaganda, and prestige motivated wealthy individuals to sponsor artists across the ages.

Art patronage—the financial and material support provided by wealthy individuals, families, or institutions to artists—has been the primary engine of artistic production throughout human civilization. Understanding how rich people have shaped art reveals crucial insights into power structures, cultural values, and the evolution of artistic freedom across different eras and societies.

What Is Art Patronage? The Historical Foundation

Before diving into four millennia of patronage history, we need to understand what patronage actually meant in practice and why it dominated artistic production for so long.

Defining Patronage: More Than Just Financial Support

Art patronage encompasses far more than simply writing a check to an artist. True patronage provided comprehensive support: expensive materials like marble, gold leaf, or rare pigments; dedicated workspace in palaces or studios; social connections to other wealthy commissioners; and often physical protection from legal troubles or rival artists.

The word “patron” derives from the Latin patronus, meaning protector or father figure—someone who provides benefits to those under their care. The term “mecenate,” used in Romance languages for patron, comes from Gaius Maecenas, the generous friend and advisor to Roman Emperor Augustus who famously supported poets and artists.

Patronage differs fundamentally from art collecting. Patrons commission the creation of new artworks, providing support during the production process and often specifying exactly what should be created. Collectors, by contrast, acquire already-completed works, choosing from what exists rather than directing what gets made. Throughout history, many wealthy individuals functioned as both patrons and collectors, but the relationship to artists differed dramatically.

The Core Functions of Patronage Throughout History

Why did wealthy people spend fortunes commissioning art? The motivations were remarkably consistent across millennia and cultures:

Display of wealth and power topped the list. Commissioning expensive artworks demonstrated to rivals, subjects, and visitors that the patron possessed resources to spare on non-essential luxuries. The very act of patronage was a power move.

Political propaganda and legitimization proved equally important. Rulers from ancient Mesopotamia to Renaissance Italy used commissioned art to justify their authority, connect themselves to divine powers or classical predecessors, and communicate their fitness to rule.

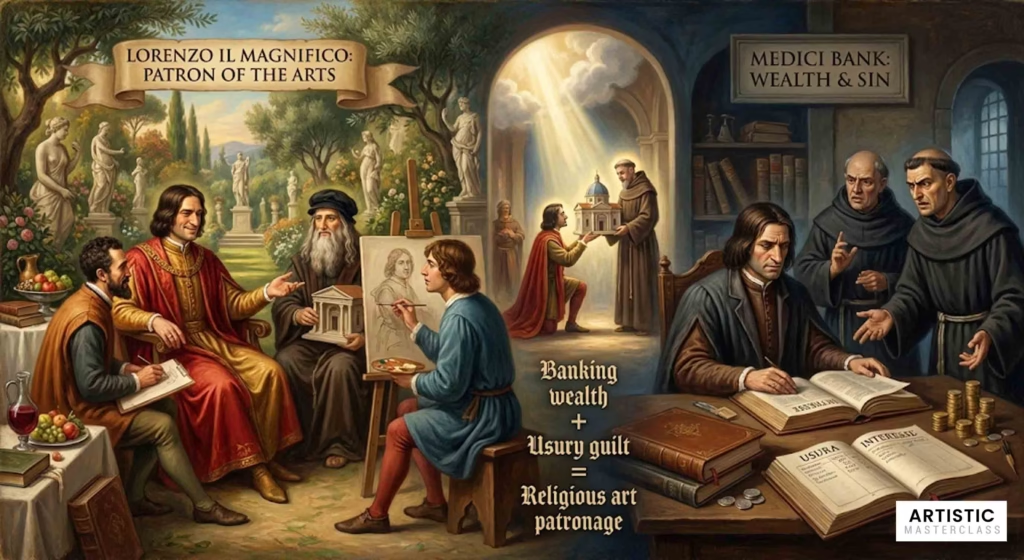

Religious devotion motivated enormous expenditures. Commissioning religious art demonstrated piety, sought divine favor, and sometimes served as atonement for sins like usury—the lending of money at interest, considered sinful in medieval Christianity.

Legacy preservation appealed to patrons’ desire for immortality. Without commissioned statues, portraits, and monuments, most wealthy individuals would be completely forgotten. Art patronage bought a kind of eternal life through remembrance.

Cultural prestige and refinement separated the merely wealthy from the truly cultivated. Patrons demonstrated their education through art commissions packed with classical references that only the learned could fully decode.

The Patron-Artist Dynamic: A Complex Relationship

The relationship between patron and artist was fundamentally unequal, despite Renaissance romanticism about artistic genius. Patrons held economic power; artists needed income. This imbalance shaped everything about how art was created.

In most historical periods, artists only created works after receiving specific commissions. The Renaissance system called mecenatismo formalized this arrangement. Detailed contracts specified the total cost, timeline, materials to be used, and often the exact subject matter and composition. Some contracts even included preliminary sketches showing precisely what the patron expected.

Patrons could control remarkably specific details: which pigments were used (ultramarine blue made from crushed lapis lazuli cost more than gold), how many figures appeared, what clothing they wore, and whether the patron’s own likeness appeared in the work. Renaissance noblewoman Isabella d’Este famously sent detailed instructions to artists about every element of compositions she commissioned.

Court artists occupied a special category. Rather than working project-by-project, they received permanent positions with wealthy families or royal courts, receiving salaries and sometimes housing, land grants, or tax exemptions. Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea Mantegna both served as court artists, though their surviving correspondence reveals constant battles over promised but unpaid wages.

The power dynamic slowly shifted during the Renaissance as humanist thought began recognizing artists as uniquely talented individuals rather than mere craftsmen. By the era’s end, the most renowned artists commanded higher fees and negotiated greater creative control. But even Michelangelo, one of history’s most celebrated artists, had to follow his patrons’ specifications and sometimes fled cities when relationships with powerful patrons soured.

Ancient World Patronage (3000 BCE – 500 CE): Kings, Pharaohs, and Emperors

Long before the Medici family or Catholic popes commissioned Renaissance masterpieces, ancient civilizations established patronage as the foundation of artistic production. Kings, pharaohs, and emperors understood that art could communicate power, ensure remembrance, and honor the gods.

Mesopotamia: Gudea and the Birth of Artistic Patronage (2144-2124 BCE)

The Mesopotamian ruler Gudea provides one of history’s earliest and most compelling examples of personal artistic patronage. Though Gudea ruled only a section of Sumeria for about twenty years, archaeologists have discovered and classified 27 statues of this king—among the most cherished artifacts of the Ancient Near East. Nearly half now reside in major museums including the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Each statue shares recognizable features: broad-shouldered upright pose, clutched hands, similar facial features, and consistent dress. Based on where they were found and their inscriptions, scholars know these statues functioned as stand-ins for Gudea in temples throughout his realm. They served dual purposes: demonstrating the king’s piety to the gods and, equally important, displaying his wealth and power to temple visitors.

The material choice itself communicated power. Most of Gudea’s statues were carved from diorite, the same dark, hard-to-work stone Egyptian pharaohs used for their portraits. Diorite was notoriously difficult to carve and extremely rare, requiring expensive quarrying operations and long-distance transport. Gudea’s marshaling of this costly stone honored the gods while simultaneously heaping glory on himself.

The gambit worked spectacularly. Despite ruling only one portion of the Fertile Crescent for just two decades four thousand years ago, Gudea’s patronage of the arts has furnished him with lasting fame. Much of what we know about him comes from these commissioned statues and the inscriptions they bear. Art patronage bought him immortality.

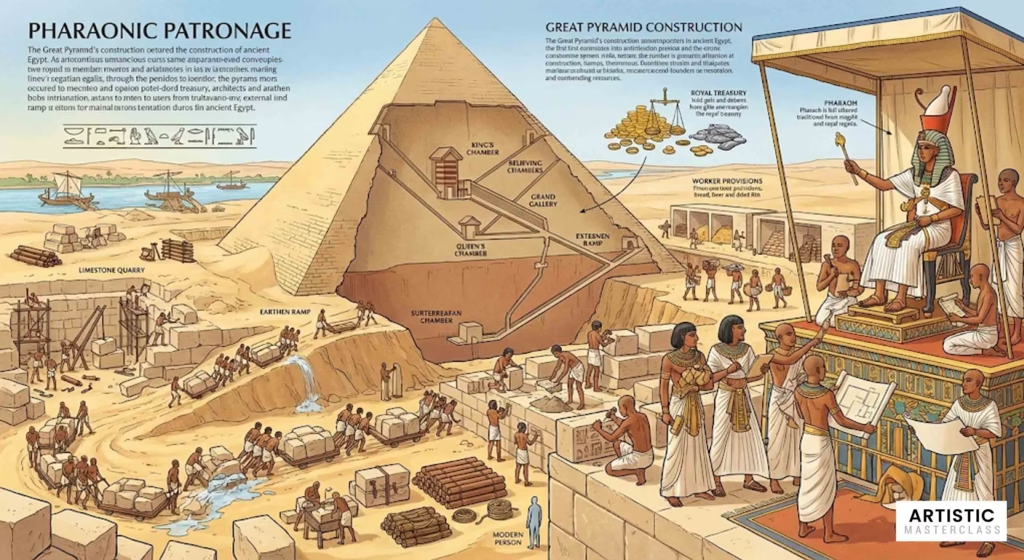

Ancient Egypt: Pharaonic Commissions and Elite Patronage

In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh functioned as the ultimate art patron, commanding resources to build pyramids, temples, and monumental statuary on a scale that still astonishes. The construction of the Great Pyramids required organizing tens of thousands of workers and monopolizing Egypt’s wealth for decades—patronage as state project.

Royal control extended to materials. Pharaohs controlled access to gold, precious stones, and quality imported wood, making truly fine art possible only through royal commission or permission. This monopoly ensured that the grandest artistic achievements served the state and its ruler.

Wealthy elite Egyptians also commissioned art, particularly for tombs. The Old Kingdom tomb relief “Ti Watching a Hippopotamus Hunt” exemplifies wall reliefs popular with wealthy patrons around 2400 BCE. These works depicted scenes from everyday life, religious themes, and the patron’s achievements, ensuring the deceased would be remembered and that their afterlife would include the activities they enjoyed.

Egyptian art followed strict conventions regarding proportions, composition, and iconography. Yet even within these rigid standards, patrons could specify details about their own portraits, the scenes depicted, and the quality of materials and execution. The system balanced standardization with individual patron preferences.

Ancient Greece: From City-States to Alexander’s Empire

Ancient Greek patronage evolved alongside Greek political structures. In Athens during its golden age, philosopher-kings and wealthy citizens sponsored public art that celebrated civic values and democratic ideals. The sculptor Phidias and painter Apelles worked for elite patrons who understood art as both cultural achievement and political statement.

City-state rivalries drove competitive patronage. Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and other cities commissioned temples, statues, and public monuments partly to outshine rivals. Artistic achievement became a measure of civic greatness, spurring investment in patronage.

Alexander the Great’s conquests created a new patronage model. As his empire spread across Asia, North Africa, and Europe, Alexander and his generals established cultural centers in distant territories. The Hellenistic period saw royal patronage flourish in Alexandria (Egypt) and Antioch (Syria), where great wealth enabled sponsorship of ambitious artistic projects.

Greek artists, unlike their Egyptian counterparts, began to be recognized as individuals. We know the names of major Greek sculptors and painters because their achievements were recorded and celebrated. This shift from anonymous craftsman to recognized artist would accelerate dramatically in the Renaissance, but its roots lay in Greek patronage patterns that valued individual artistic genius.

Ancient Rome: Imperial Patronage and Luxury Arts

Rome’s conquest of the Mediterranean world concentrated unprecedented wealth in the hands of emperors, senators, and successful merchants. This wealth fueled extensive artistic patronage, though Romans also simply looted art from conquered territories, particularly Greek masterpieces.

Emperor Augustus transformed Rome through artistic patronage, commissioning temples, monuments, and public buildings that communicated Rome’s power and his own legitimacy as ruler. Later emperors continued this pattern, using art and architecture as political propaganda on a massive scale.

Wealthy Roman patricians functioned as private patrons, commissioning portraits, collecting sculpture, building elaborate villas, and surrounding themselves with luxury arts. During the late Republic, fortunes from trade, banking, and conquest enabled patronage that sometimes rivaled imperial expenditures. Men like Marcus Licinius Crassus became enormously rich and used wealth to commission art, build palaces, and form private collections.

Roman luxury arts reached remarkable sophistication. Jewelry incorporating rare pearls from the Persian Gulf, emeralds from Egypt, and amber from the Baltic Sea displayed patron wealth. Cameo glass, mosaic glass, and elaborate metalwork demonstrated both patron resources and artist skill. Fayum mummy portraits from Roman Egypt—realistic painted portraits attached to mummies—show wealthy Greeks and Romans commissioning highly personal artworks blending Egyptian funerary traditions with Greco-Roman artistic style.

Rome’s relationship with Egyptian art exemplifies complex patronage dynamics. After Augustus conquered Egypt in 30 BCE, Roman elites became fascinated with Egyptian culture. They commissioned Egyptian-style obelisks and sculpture for Roman settings, imported actual Egyptian artifacts, and had Roman craftsmen create “Egyptianizing” works. The distinction between authentic Egyptian art and Roman-made Egyptian-style art mattered less than the prestige these objects conferred on wealthy collectors and patrons.

Medieval Patronage (500-1400 CE): The Church as Supreme Patron

During Europe’s medieval period, the Catholic Church emerged as history’s most powerful institutional art patron. For roughly a thousand years, the Church directed the majority of artistic production in Europe, shaping not just religious art but the entire visual culture of the era.

The Catholic Church: History’s Most Powerful Institutional Patron

No patron in history—not the richest merchant families, not the most powerful emperors, not the largest foundations—matched the Catholic Church’s influence on artistic production. With vast accumulated wealth, property throughout Europe, and a coordinated institutional structure, the Church could fund artistic projects on a scale and duration impossible for individual patrons.

Funding came from multiple sources: tithes paid by Christians, church-owned lands and businesses, fees for religious services, and accumulated donations. This steady income stream enabled the multi-generational projects required for great cathedrals, which sometimes took a century or more to complete.

Cathedral building represented patronage on an epic scale. The Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris, begun in 1163, required nearly two centuries to complete. Countless sculptors, glass makers, metalworkers, and other craftsmen found lifelong employment on such projects. The Church didn’t just commission finished artworks; it sustained entire artistic industries.

Manuscript illumination flourished under monastic patronage. Monks in scriptoriums produced elaborately decorated books—religious texts, histories, and scholarly works—that rank among medieval Europe’s greatest artistic achievements. These labor-intensive works required expensive pigments, gold leaf, and skilled hands working for months or years. Only wealthy monastic orders could sustain such production.

Religious art served multiple functions for the Church. Beautiful churches and inspiring artworks attracted congregants and pilgrims, generating income. Sacred art taught Christian doctrine to largely illiterate populations—the “Bible for the illiterate,” as Gregory the Great described it. And impressive religious art demonstrated the Church’s power, wealth, and divine favor.

The Church as patron exercised significant control. Iconographic requirements were strict: Jesus needed long hair and a beard; the Virgin Mary wore blue; saints required their identifying attributes (Saint Peter with keys, Saint Francis with animals). Contracts for church commissions specified not just technical details but theological accuracy.

Royal and Noble Patronage in Feudal Europe

Medieval kings, queens, and aristocrats also functioned as important patrons, though their resources rarely matched the Church’s institutional wealth. Royal patronage focused on projects that reinforced political authority: castles, palaces, royal chapels, and artworks celebrating lineage and legitimizing claims to power.

The Bayeux Tapestry, created around 1070, exemplifies medieval aristocratic patronage. Commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux (who was also William the Conqueror’s half-brother), this 70-meter embroidered narrative depicts the Norman conquest of England. It served as both historical record and propaganda justifying Norman rule.

Aristocratic families commissioned portraits, heraldic designs, tapestries, and decorative arts that communicated their status within feudal hierarchies. Family chapels and tombs received special attention, as nobles sought to ensure their remembrance and spiritual well-being after death.

Guild Patronage and Civic Projects

Medieval cities saw the emergence of collective patronage through merchant guilds and confraternities. These organizations pooled resources to commission art for civic buildings, guild halls, and shared religious chapels. This represented a significant shift: patronage was no longer exclusively the domain of kings, aristocrats, and the Church.

Guild patronage foreshadowed the merchant-class dominance that would characterize Renaissance patronage. Successful tradesmen and merchants, though not aristocratic, possessed wealth and began using it for cultural projects. This created space for a new patron class that would eventually challenge aristocratic and ecclesiastical monopolies on artistic commissioning.

Renaissance Patronage (1400-1600): The Golden Age of Patron Power

The Renaissance represents the most celebrated period of art patronage in Western history. During these two centuries, individual families, papal patrons, and wealthy merchants commissioned artworks that defined European culture for centuries to come. The relationship between patron and artist reached new levels of sophistication, producing masterpieces while also revealing the tensions inherent in patronage systems.

The Medici Dynasty: Banking Wealth Transformed Into Cultural Power

No family better exemplifies Renaissance patronage than the Medici of Florence. Their rise from successful merchants to de facto rulers of Florence, and eventually to providing four popes, was built partly on art patronage. They understood that commissioning art wasn’t just about beauty—it was about power.

Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464), the family patriarch, established the patronage tradition that would make Florence the cultural capital of Europe. After amassing a fortune through banking—the Medici revolutionized the industry by introducing double-entry bookkeeping still used today—Cosimo became one of the wealthiest men in Italy and Florence’s unofficial ruler.

Cosimo’s patronage supported Donatello, whose bronze “David” (c. 1428-32) became the first free-standing nude sculpture since antiquity. He funded Fra Angelico’s frescoes that adorned Florentine churches and commissioned Filippo Brunelleschi’s architectural projects, including the magnificent dome of Florence Cathedral—still an engineering marvel six centuries later.

Critically, Cosimo extended patronage beyond visual arts to libraries and humanist scholarship. He understood that cultural prestige came from supporting all intellectual endeavors, creating an ecosystem where art, literature, and philosophy flourished together. This comprehensive approach to patronage helped Florence dominate the Renaissance more completely than any rival city.

Lorenzo “the Magnificent” de’ Medici (1449-1492) elevated the family’s patronage to legendary status. Lorenzo commissioned works from Leonardo da Vinci (early in Leonardo’s career), Michelangelo (whom Lorenzo recognized as a prodigy), and Sandro Botticelli. His patronage of Botticelli produced “Primavera” (c. 1482) and “The Birth of Venus” (c. 1484-86), works so dense with classical references and symbolic meaning that they functioned as conversation pieces at elite gatherings, allowing the educated to demonstrate their knowledge of antiquity.

Lorenzo transformed patronage into personal relationships. Rather than maintaining cold contractual distance, he included favored artists in his inner circle, hosted them in Medici palaces, and treated them as intellectual equals. This elevation of artists from craftsmen to respected individuals marked a crucial shift in how society viewed artistic creation.

Later Medici family members who became popes—Leo X and Clement VII—continued the patronage tradition in Rome. Clement VII commissioned Michelangelo to paint “The Last Judgment” (1534) in the Sistine Chapel, one of the most powerful religious artworks ever created.

The Medici Chapel commission of 1520 to Michelangelo reveals patronage’s complex motivations. The project was partly pious (creating a proper burial place), partly political (glorifying the family), and partly an attempt at atonement. The Medici wealth came from banking, which involved charging interest—usury, considered sinful in Catholic doctrine. Commissioning lavish religious art served to “cleanse” this questionably obtained wealth, buying spiritual redemption through artistic patronage.

Papal Patronage: The Vatican as Artistic Powerhouse

The popes of the Renaissance wielded enormous wealth and used it to transform Rome into Christendom’s artistic capital. Papal patronage surpassed even the Medici in scale and ambition, though it also sparked controversies that contributed to the Protestant Reformation.

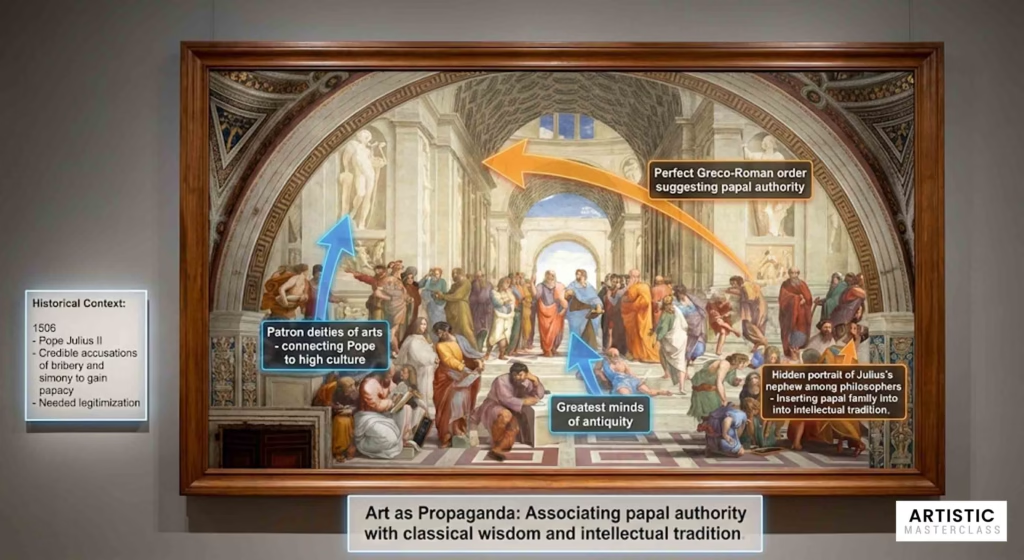

Pope Julius II (1503-1513) stands as perhaps history’s most ambitious papal patron. In 1506, he made the audacious decision to demolish the original St. Peter’s Basilica and rebuild it as the grandest church in Christendom. This project consumed decades and the labor of the Renaissance’s greatest architects, including Bramante, Michelangelo, and later Bernini.

To fund such massive expenditures, the Church taxed Christians throughout Europe. These payments directly funded Julius’s artistic vision, including Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-12) and Raphael’s “School of Athens” (1509-11).

Raphael’s fresco for Julius’s personal library deserves special attention. “The School of Athens” places the greatest philosophers of classical antiquity—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, and others—in a perfectly ordered plaza of Greco-Roman architecture. Marble statues of Apollo and Minerva, patron god and goddess of the arts, preside over the scene. The work communicated Julius’s connection to intellectual tradition and high culture.

But there’s a darker context. Julius had marched on Italy twice under French banners trying to seize the papacy from rivals, and credible accusations suggested he’d obtained his position through bribery and simony (selling church offices). Commissioning art that glorified Christianity and connected his papacy to noble intellectual pursuits helped legitimize his controversial reign. Art was propaganda.

The irony and hypocrisy of papal patronage didn’t escape critics. The Church preached humility, charity, and spiritual values while commissioning incredibly expensive art and architecture that glorified institutional power and papal authority. The direct tax on Christians to fund these projects—particularly the sale of indulgences, literally selling spiritual forgiveness to raise money—became a major grievance for Martin Luther and Protestant reformers.

Yet it’s hard to deny the cultural achievement. Without papal patronage, the Sistine Chapel ceiling wouldn’t exist. The Vatican museums housing incomparable art collections wouldn’t exist. St. Peter’s Basilica wouldn’t exist. The question remains: was this worth the cost in Christian unity and the spiritual compromises involved?

Aristocratic Patrons: Sforza, Borgia, and d’Este Families

Beyond the Medici and popes, numerous aristocratic families competed to outdo each other through artistic patronage. Political rivalry manifested as cultural competition.

Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from 1494-1499, brought Leonardo da Vinci to his court. Sforza commissioned Leonardo to paint “The Last Supper” (1495-98) for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. This masterpiece demonstrates both Renaissance artistic innovation—Leonardo’s experimental technique and psychological drama—and the power of ducal patronage to enable such ambitious works.

Importantly, Sforza didn’t hire Leonardo only to paint. The artist also served as military engineer, designing weapons and fortifications. Court artists often fulfilled multiple functions, from decorating bedrooms to designing army flags. This versatility was expected, and the greatest artists commanded premium compensation for their diverse talents.

Isabella d’Este (1474-1539), Marchioness of Mantua, ranks among the Renaissance’s most significant female patrons. She transformed her court into a cultural center, commissioning works from Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, Giovanni Bellini, Correggio, and other leading artists.

Isabella’s “studiolo”—a private study decorated with allegorical paintings—showcased how patrons could set thematic programs. She maintained active correspondence with artists, specifying iconographic details and expecting precise execution of her vision. Isabella wasn’t merely funding art; she was directing its creation with exacting standards. Her extensive art commissions demonstrated her refined taste, political power, and intellectual sophistication at a time when women rarely wielded such cultural influence.

The Borgia family also used art patronage strategically. Though remembered today primarily for their ruthless politics and alleged crimes, the Borgias understood art’s propaganda value and commissioned works that projected legitimacy and power. Art helped rehabilitate reputations and distract from controversial actions.

How Renaissance Patronage Actually Worked

To truly understand Renaissance patronage, we need to examine the practical mechanisms—how commissions were negotiated, what patrons could control, and how artists navigated these relationships.

The contract system, or mecenatismo, formalized patron-artist relationships. Detailed written agreements specified:

- Total cost and payment schedule: Often an advance payment, installments during work, and final payment upon delivery

- Timeline: Completion deadlines, sometimes with penalties for delays

- Materials: Quality and quantity of pigments, gold leaf, stone, or other materials; expensive pigments like ultramarine blue (made from crushed lapis lazuli) cost more than gold and contracts specified whether these should be used

- Subject matter: Exact scenes, figures, and composition elements

- Quality standards: Sometimes contracts included sketches showing expected results

Example contracts reveal remarkable specificity. Isabella d’Este’s agreements with artists specified not just the subject but the positioning of figures, their expressions, the colors of their clothing, and background details. She actively micromanaged commissions, sending follow-up letters demanding adjustments if preliminary work didn’t meet her vision.

Patrons exercised control that would shock modern sensibilities about artistic freedom. They could specify:

- Whether the patron’s own portrait appeared in religious scenes (a common practice called “donor portraits”)

- The exact number and arrangement of figures

- Colors used for specific elements

- Background architecture and landscape features

- Whether and how the patron’s coat of arms was displayed

- Size and format of the work

Court artists represented a different model. Rather than project-by-project commissions, these artists received permanent positions with wealthy families or royal courts. Benefits included regular salaries, housing (sometimes in the patron’s palace), and social status elevation. Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea Mantegna both served as court artists, though both also left extensive correspondence complaining about patrons who delayed or withheld promised payments.

For the very best artists, compensation went beyond cash. Court positions could include tax exemptions, land grants, titles, and patches of forest. These perks were necessary because even illustrious patrons could be notoriously slow to pay.

Litigation wasn’t uncommon. Contracts were legally binding, and artists could sue patrons for non-payment while patrons could sue artists for work deemed inadequate. These disputes reveal the tensions inherent in patronage: artists wanted payment and creative respect; patrons wanted exactly what they ordered, delivered on time and budget.

The most successful artists used completed commissions to build reputations that gave them leverage for future negotiations. By the Renaissance’s end, renowned artists like Michelangelo could demand creative control and even refuse commissions from insufficiently prestigious or difficult patrons. But this freedom was hard-won and available only to a small elite of celebrated artists.

Portraits as Status Symbols: Women as Property

Renaissance portrait commissions reveal how patronage intersected with social structures, particularly regarding women. The return of portraiture during this period signified widespread economic prosperity and the desire among wealthy families to preserve individual likenesses—but portraits of women served specific commercial purposes.

Parents commissioning portraits of daughters were essentially creating advertisements. Florence’s wealth came from textile trade—cloth, silks, and wools—and wealthy families literally displayed their products on their daughters in portrait paintings. Young women wore elaborate dresses, intricate hairstyles with woven pearls and gems, and expensive jewelry that would violate sumptuary laws (which prohibited such luxury in daily life) but were permitted in portraits.

Piero del Pollaiuolo’s “Portrait of a Woman” (1480) exemplifies this. Pearls weave through the subject’s elaborate hairstyle, demonstrating both the family’s wealth and Florence’s trade prowess. The portrait displays the young woman as valuable property.

Most of these portraits were created on or just before the woman’s wedding. Marriage in wealthy Renaissance families was fundamentally transactional—alliances between families, with the bride’s dowry attaching specific monetary value to her person. Portraits functioned as pre-wedding viewings, allowing suitors to see their bride before meeting her in person.

This practice reveals patronage’s role in reinforcing social hierarchies and treating women as commodities. The artistic beauty of these portraits shouldn’t blind us to their function within oppressive systems. Wealthy families commissioned portraits to maximize return on their investment in daughters, just as they commissioned portraits of valuable possessions, estates, and achievements.

Art as Propaganda: Decoding Hidden Messages

Renaissance patrons didn’t commission art just for aesthetic pleasure. Artworks communicated carefully crafted messages about power, legitimacy, piety, and status. Understanding Renaissance patronage requires learning to decode these messages.

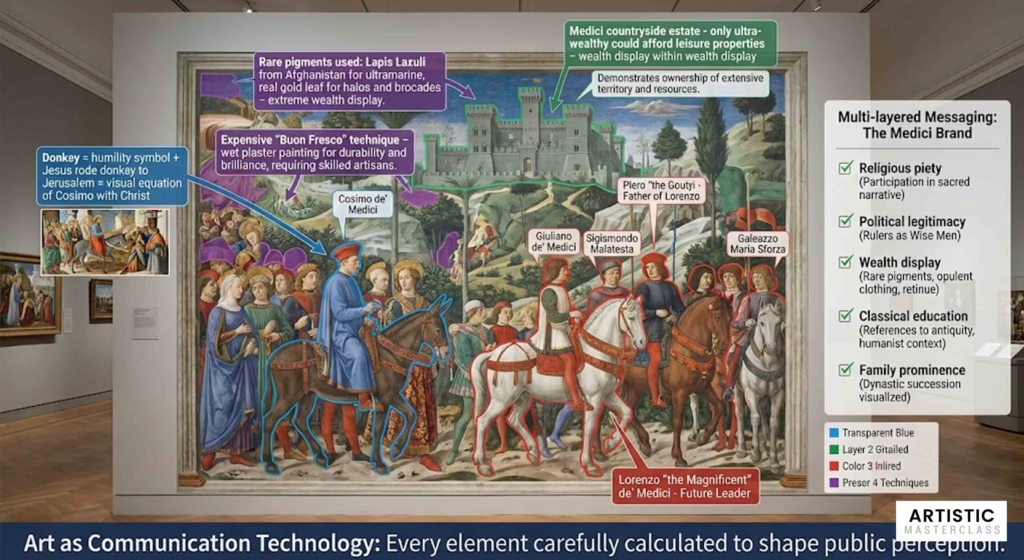

Benozzo Gozzoli’s “Procession of the Magi” (1459-62), painted across three chapel walls in Florence’s Palazzo Medici, offers a masterclass in patron self-promotion disguised as religious art. The fresco depicts the Biblical journey of the Magi to see the infant Jesus—but Gozzoli painted Medici family members directly into the scene.

Most prominently, Cosimo de’ Medici appears astride a donkey, white-haired and wearing a red hat. The donkey is significant: Cosimo was known for riding donkeys rather than horses to emphasize his modesty and humility. But there’s a deeper message—Jesus rode a donkey into Jerusalem. By depicting Cosimo on a donkey in a religious scene, the painting subtly equates the family patriarch with Christianity’s central figure.

In the background appears a magnificent gray villa on a hillside. This wasn’t random architectural decoration; it represented a countryside estate. During the Renaissance, only the extraordinarily wealthy could afford leisure properties, while most people “worked hard to get by,” as art historian Diana DePardo-Minsky notes. That villa in the background was a status symbol within a status symbol—the painting itself commissioned by wealth, depicting additional manifestations of that wealth.

The entire composition communicated multiple messages simultaneously:

- Religious piety: The Medici were good Christians commissioning appropriate religious art

- Political legitimacy: Association with Biblical events and sacred history

- Wealth and power: Expensive fresco, skilled artist, references to multiple properties

- Classical education: Composition packed with references to ancient art and literature

- Family prominence: Literally inserting family members into sacred narrative

This multi-layered messaging was precisely the point. Successful patronage created conversation pieces that demonstrated the patron’s sophistication, wealth, and power to educated viewers who could decode the references.

Raphael’s inclusion of his patron’s nephew in “School of Athens” followed similar logic. Pope Julius II’s family appeared alongside Plato and Aristotle, visual propaganda equating the papal family with history’s greatest minds.

Renaissance patrons understood something modern viewers sometimes forget: art was communication technology. Commissioning the right artworks, with the right messages, could shape public perception, legitimize authority, and create lasting impressions that outlived the patrons themselves. Four centuries later, we remember Cosimo de’ Medici partly because of the art he commissioned. The strategy worked.

The 19th Century Revolution: From Patronage to Art Market

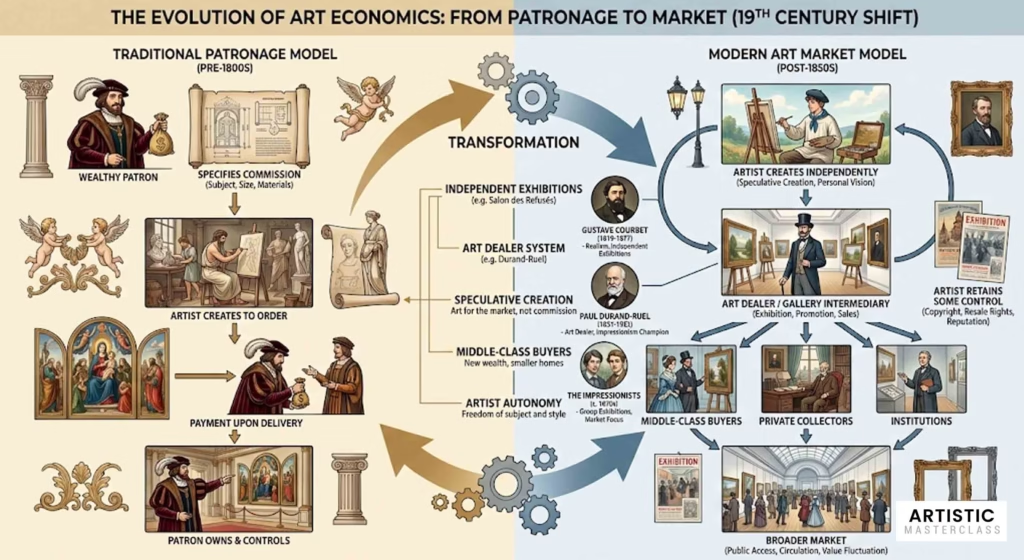

The 19th century witnessed a fundamental transformation in how art was funded, created, and sold. The aristocratic and ecclesiastical monopoly on patronage shattered, replaced by an emerging art market that gave artists unprecedented—though precarious—independence.

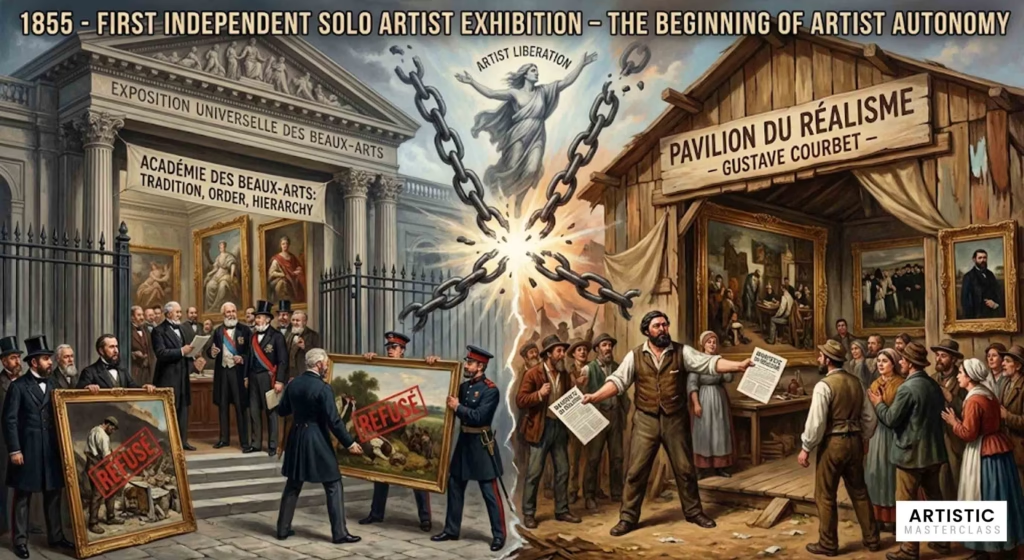

Courbet’s Rebellion: The First Independent Artist Exhibition

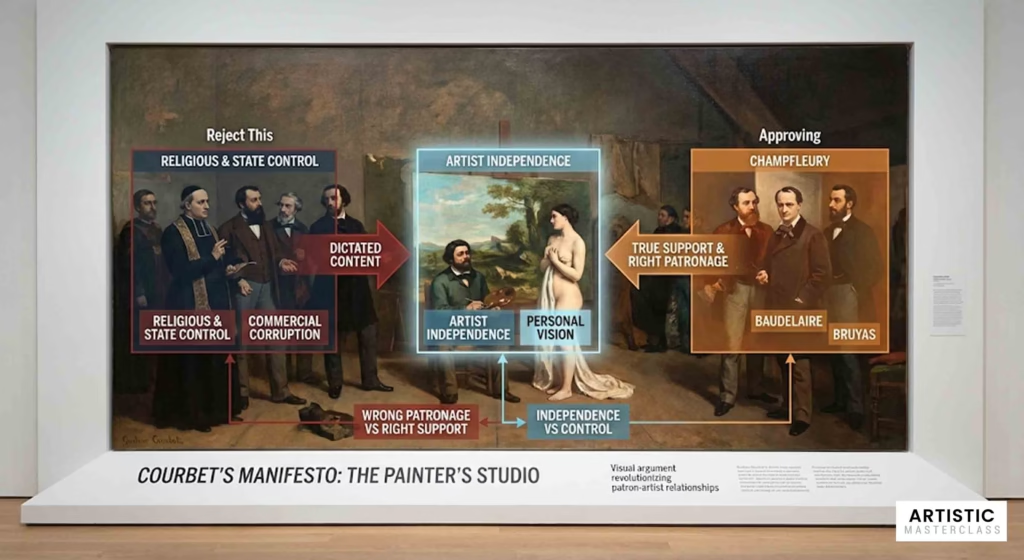

The transformation began dramatically in 1855 when French Realist painter Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) made history. That year, the French Académie des Beaux-Arts rejected three of his fourteen submissions to the Exposition Universelle, a major international exhibition in Paris. Among the refused works was “The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory of Seven Years of My Artistic and Moral Life” (1855), which the jury deemed too large to display.

Rather than accept rejection, Courbet did something revolutionary: he rented grounds adjacent to the official Exposition and erected a temporary “Pavilion du Réalisme” (Pavilion of Realism). There he displayed forty of his own works, offered them for sale, and distributed a catalog containing his Realist manifesto championing personal study of art and nature over any “preconceived system” represented by academic teaching.

This was the first documented instance of a solo artist mounting an independent exhibition. Courbet was declaring that artists could bypass traditional patronage gatekeepers—the academies, the Church, the aristocracy—and appeal directly to whoever would buy their work.

“The Painter’s Studio” itself functions as visual manifesto about patronage. In this nearly 12-by-20-foot painting, Courbet organized figures into three groups. On the left stand representations of everything wrong with the traditional art world: a priest, a merchant, a figure resembling Emperor Napoleon III, plus an impoverished couple huddled around academic still-life elements (guitar, knife, hat). These symbolize the wrong kind of patronage—state control, religious authority, academic traditions, commercial corruption.

In the center, Courbet himself paints a landscape of his hometown of Ornans while a peasant boy and a female nude look on admiringly. He works independently, creating his personal vision, literally at the center of the composition.

On the right stand Courbet’s genuine supporters: art critic Champfleury, poet Charles Baudelaire, anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and most importantly, his patron Alfred Bruyas. This represents the right kind of support—intellectual peers and patrons who respected his artistic vision rather than dictating it.

The composition argues visually for a new patronage model where patrons support rather than control, where artists create first and find buyers second, where artistic integrity matters more than patron specifications.

Rise of Art Dealers and the Gallery System

Courbet’s rebellion signaled broader changes already underway. Artists were beginning to work speculatively—creating artworks on their own initiative, then seeking buyers—rather than waiting for commissions. This required new intermediaries.

Art dealers emerged to bridge the gap between artists and buyers. Paul Durand-Ruel became perhaps the most influential 19th-century dealer, almost single-handedly championing the Impressionist movement. He purchased thousands of works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Claude Monet throughout his life, providing these artists crucial income before their style gained acceptance.

Durand-Ruel functioned as a new kind of patron—not commissioning specific works but rather purchasing completed paintings, offering steady income that freed artists to develop their personal styles. This shifted power dynamics significantly. Artists created what they wanted; dealers risked their own money betting on which artists would ultimately find buyers.

The Impressionists, repeatedly rejected by the official Salon, organized their own independent group exhibitions starting in 1874. These were direct descendants of Courbet’s Pavilion of Realism but involved multiple artists supporting each other collectively. The Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected) displayed works spurned by official channels, challenging the academy’s monopoly on defining acceptable art.

These developments created space for middle-class art buyers. You no longer needed aristocratic wealth to commission art; you could simply purchase completed works at more moderate prices from galleries. This democratization of art buying fundamentally changed market dynamics.

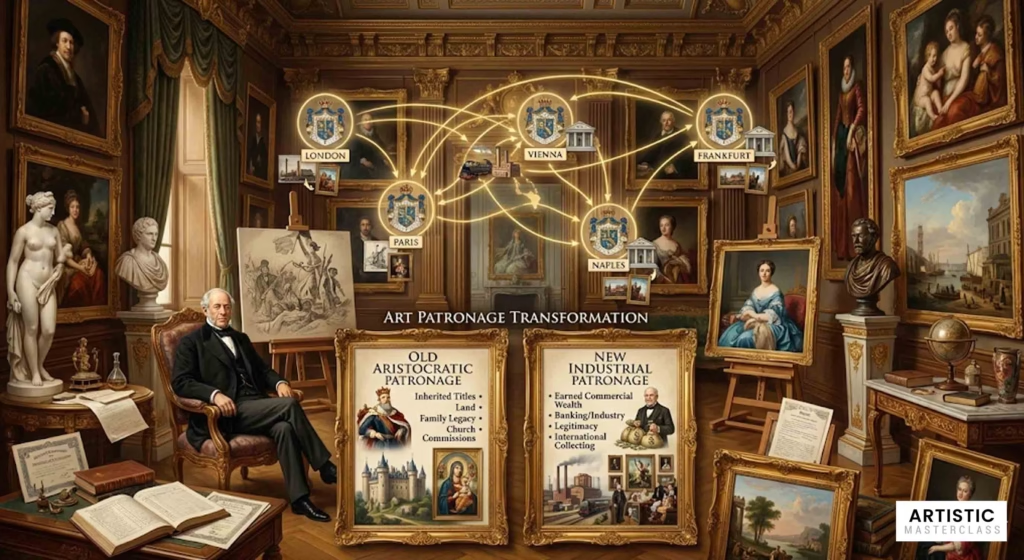

Industrial Fortunes Creating New Patron Class

The 19th century also saw industrial and financial wealth create a new patron class rivaling old aristocracy. The Rothschild family exemplifies this transformation.

The Rothschilds, who built a banking empire across Europe, became prolific art patrons throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Family members like Baron James de Rothschild in France and Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild in Austria supported artists including Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Franz Xaver Winterhalter. They amassed extensive collections blending Old Masters with contemporary artists.

Rothschild patronage differed from earlier aristocratic models in important ways. They collected more than commissioned. They accumulated cultural capital to legitimize their recent wealth and social position. And they operated across national boundaries, treating art as international high culture rather than localized expression.

In America, industrialists like J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Clay Frick would extend this pattern into the 20th century, using art patronage and collecting to establish cultural legitimacy. The Gilded Age saw factory owners and financiers transform themselves into art patrons, though their role as collectors and museum founders often overshadowed direct patronage of living artists.

The 19th century transformation didn’t eliminate patronage—it pluralized it. Artists now had multiple potential income sources: private commissions, dealer relationships, direct sales, academic positions, government grants. This diversity gave artists more leverage but also more precarious careers. The myth of the “starving artist” emerged precisely when artists gained independence from patronage, because that independence came with financial uncertainty.

20th Century Patronage: Foundations, Museums, and Modern Art

As the 20th century dawned, art patronage adapted to new wealth sources and institutional forms. Family foundations, museum endowments, and individual collectors shaped artistic movements—particularly modernist styles that required avant-garde patron support.

The Guggenheim Legacy: Championing Modern Art

The Guggenheim family wrote one of the 20th century’s most influential patronage stories, championing modern and abstract art when it lacked commercial viability or public acceptance.

Solomon R. Guggenheim (1861-1949) made his fortune in mining and industry, then turned to art collecting and patronage. In 1937, he founded the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, dedicated to promoting modern art. This culminated in the 1959 opening of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright as an architectural masterpiece that became nearly as famous as the art it housed.

Solomon focused on non-objective art and supported abstract expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. These artists created large-scale abstract works that most buyers found baffling or ugly. Without Guggenheim support providing both funding and institutional legitimacy through museum exhibitions, Abstract Expressionism might never have achieved its revolutionary impact.

Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979), Solomon’s niece, proved even more influential in directly supporting individual artists. After opening Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London in 1938, she returned to New York and launched the Art of This Century Gallery in 1942. This became the launching pad for some of 20th-century art’s biggest names.

Peggy discovered Jackson Pollock when he was unknown and struggling. She provided him monthly income, commissioned works, and gave him exhibitions. This patronage directly enabled Pollock to develop his revolutionary drip painting technique. Without monthly financial security from Peggy, Pollock might never have had the freedom to experiment so radically.

She similarly supported Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Willem de Kooning early in their careers. Her galleries provided crucial platforms before these artists found mainstream acceptance. Peggy also championed Surrealism, collecting works by Max Ernst (whom she married), and building a personal collection that eventually moved to Venice, where she opened her own museum in 1949.

The Guggenheim model represents 20th-century patronage at its best: wealthy individuals using resources to support experimental art that commercial galleries and conservative buyers rejected. The foundation structure provided institutional continuity beyond any individual patron’s lifetime, ensuring sustained support for avant-garde work.

Foundation Model and Institutional Patronage

The Guggenheims pioneered a model that many wealthy 20th-century families adopted: the arts foundation. This institutionalized patronage, creating permanent organizations that outlasted their founders.

The Rockefeller Foundation, established in 1913 by oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, funded numerous artistic and cultural projects. It provided crucial support for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, helping establish one of the world’s most influential contemporary art museums. Rockefeller patronage followed corporate philanthropy principles: strategic investment in institutions that would produce lasting cultural benefit and, not incidentally, favorable associations for the family name.

The Dia Art Foundation, founded in 1974 by art dealer Heiner Friedrich and his wife Philippa de Menil (of the wealthy de Menil family), focused specifically on large-scale minimalist works. Artists like James Turrell and Dan Flavin created installations requiring extensive space and resources—impossible without substantial patronage. Dia supported projects that commercial galleries couldn’t accommodate, enabling artistic visions that required entire buildings or outdoor spaces.

Dia’s relationship with minimalist artists resembled the Renaissance Medici-artist relationships more than modern gallery arrangements. Art historian Anna Chave noted critics coined the term “Dia-Fied” artists—a “mutual admiration society” where patron and artist affirmed each other. Dia provided resources; artists created works that justified Dia’s vision. This symbiotic relationship shaped Minimalism’s development and aesthetic.

The foundation model fundamentally transformed patronage. Rather than individual patrons commissioning specific works, foundations provided sustained institutional support, funded exhibitions, acquired works for permanent collections, and championed entire movements. Boards of directors replaced individual patron taste, potentially democratizing decisions but also creating new gatekeeping structures.

Controversial Patronage: When Patrons and Artists Clash

Not all patron-artist relationships ended happily. Conflicts revealed that even in the 20th century, economic power gave patrons ultimate control.

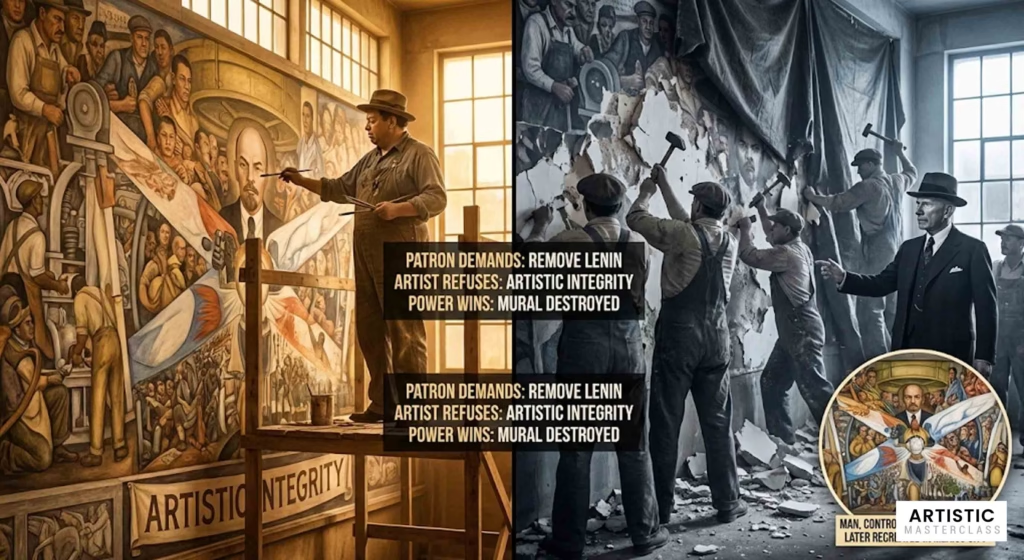

The most famous collision occurred in 1932 when American industrialist John D. Rockefeller Jr. commissioned Mexican muralist Diego Rivera to paint a mural inside Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller knew Rivera’s radical left-wing politics, and they agreed in advance on the mural’s subject: “Man at the Crossroads” would show someone looking with uncertainty but hope toward a better future.

But at the last minute, Rivera altered his design dramatically. The final mural filled with hundreds of figures illustrating dominant political ideologies, including—most problematically for his patron—a prominent portrait of Vladimir Lenin. Rumor suggested Rivera also depicted Rockefeller himself drinking martinis with a prostitute.

Rockefeller demanded changes. Rivera refused. Rockefeller then exercised his ultimate power: he had the unfinished mural covered, later chipping it off the wall entirely and destroying it. Rivera’s artistic vision died on Rockefeller’s order, demonstrating that patronage relationships—even in the ostensibly liberated 20th century—ultimately rested on economic power.

The destroyed mural became legendary, symbolizing the tension between artistic freedom and patron control. Rivera later recreated the work in Mexico City, but the original destruction stands as a reminder that accepting patronage means accepting potential constraints.

Not all artist responses to institutional power involved patron relationships. Keith Haring painted his “Crack is Wack” mural (1986) on a handball court in East Harlem without commission or permission—a deliberate assertion of artistic independence and social commentary. Yet even Haring worked extensively with patrons throughout his career, including the Catholic Church, which commissioned him to decorate a wall in the Church of Sant’Antonio in Pisa in 1989. The most independent artists still navigated patronage relationships alongside their autonomous work.

Corporate and Celebrity Collectors

The late 20th century saw new patron types emerge: celebrity collectors who used wealth and fame to shape artistic careers, and corporations embracing art sponsorship as brand strategy.

Charles Saatchi, the British advertising mogul, became notorious for his ability to make or break artistic careers through collecting. In the 1990s, he championed the Young British Artists (YBAs), launching careers for Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and others. His 1997 “Sensation” exhibition at his private gallery introduced these artists to international attention.

Saatchi functioned as patron-kingmaker. Artists he collected became valuable; those he ignored or later sold struggled. This concentration of power in a single collector’s hands recalls earlier patronage eras when a royal or papal commission could establish an artist’s reputation. The difference: Saatchi bought completed works rather than commissioning specific pieces, yet his influence on what artists created (knowing what “Saatchi-style” work meant) was profound.

Corporate sponsorship expanded throughout the 20th century. Companies discovered that funding arts events, supporting artists, and displaying corporate collections enhanced brand prestige. This created new patronage streams but raised questions about artistic independence. When Pepsi or BMW sponsored exhibitions or supported artists, did corporate interests influence artistic decisions?

The debate continues: some see corporate patronage as benign support enabling art that wouldn’t otherwise exist. Others worry that corporations expect art that enhances rather than challenges their brand, creating subtle censorship through economic incentives.

21st Century Patronage: Digital Age and Democratization

Art patronage hasn’t disappeared in the 21st century—it’s fragmented and democratized through technology while also concentrating in new ways through ultra-wealthy collectors and corporate sponsors.

Crowdfunding and Platform Patronage

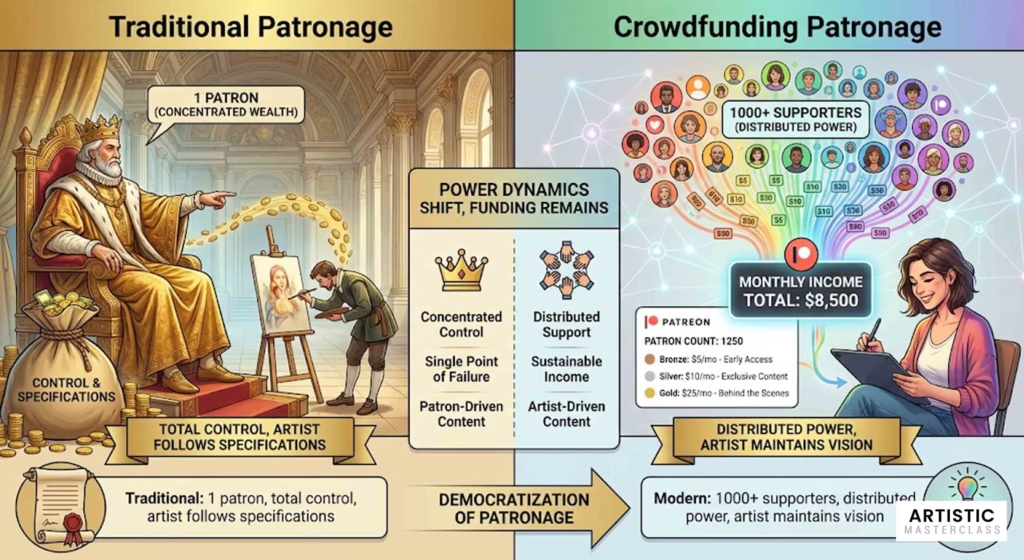

The internet enabled a revolution in patronage structure. Platforms like Patreon (launched 2013) explicitly revived historical patronage models but democratized them. Rather than single wealthy individuals funding artists, numerous small supporters provide monthly subscriptions.

On Patreon, thousands of artists receive recurring income from fans who pay $5, $10, or $50 monthly for exclusive content, early access, or simply to support work they value. This collective patronage model distributes power across many supporters rather than concentrating it in elite patrons.

The financial impact can rival traditional patronage. Successful Patreon creators earn five or six-figure annual incomes—enough to work full-time on their art without commercial gallery representation, museum grants, or wealthy individual patrons.

But there are crucial differences from historical patronage. Patreon supporters generally don’t commission specific works or direct artistic content (though some tier rewards involve commissions). Artists maintain creative control while supporters fund what artists choose to create. Power dynamics shift significantly toward artist autonomy.

Kickstarter and similar platforms enable project-specific funding. Artists pitch specific works, supporters pledge funds, and projects proceed if funding thresholds are met. This resembles historical commission-based patronage but with hundreds or thousands of small patrons replacing single wealthy commissioners.

The question remains whether “democratization” accurately describes these platforms. Access requires internet connectivity, platform literacy, marketing skills, and often pre-existing audiences. Artists lacking these advantages struggle regardless of talent. Digital patronage creates new opportunities but also new exclusions.

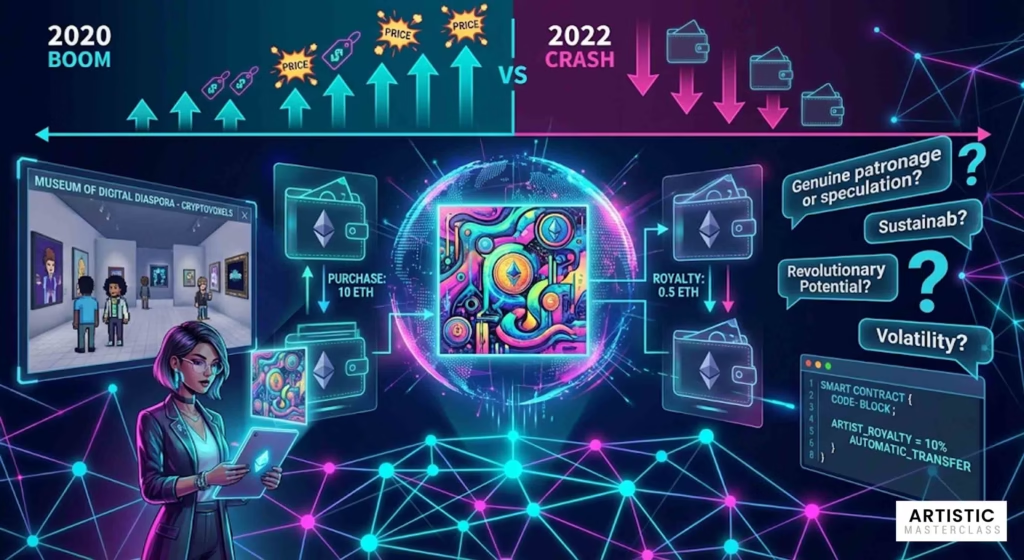

NFTs and Crypto Art Patronage

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) introduced another patronage model starting around 2017-2020. Digital artists could sell unique blockchain-verified artworks, sometimes for enormous sums. Collectors purchasing NFTs functioned as patrons enabling digital art creation.

Lady Phe0nix emerged as an influential NFT patron and curator. She founded Universe Contemporary, Crypto Club Basel, and the Museum of Digital Diaspora on Cryptovoxels (a virtual world). Her endorsement could make an artist’s career, functioning similarly to how Peggy Guggenheim’s support launched Abstract Expressionists.

NFT patronage differs from traditional models in important ways. Transactions are public and transparent via blockchain. Resale royalties can provide artists ongoing income—something unprecedented in physical art markets. And the barrier between patron and artist often dissolves, with patrons also sometimes being artists, collectors, and community participants simultaneously.

Critics argue NFTs represent speculation rather than genuine patronage—buyers hoping for price appreciation rather than supporting artistic creation. The 2022 crash in NFT values lent credence to this concern, as many collectors disappeared when prices fell.

Yet even skeptics acknowledge NFTs enabled some artists to earn significant income from digital work that previously lacked monetization mechanisms. Whether this represents a sustainable new patronage model or a speculative bubble remains debated.

Corporate Sponsorship and Brand Collaborations

Twenty-first century corporations continue 20th-century patronage trends while creating new collaboration models. Fashion houses particularly embraced art patronage as brand strategy.

The Louis Vuitton Foundation, created by luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, opened a Paris museum in 2014 showcasing contemporary art. This represents traditional corporate patronage: wealthy company funding cultural institution bearing its name.

But brands also collaborate directly with living artists. Takashi Murakami partnered with Louis Vuitton to create limited-edition handbags featuring his distinctive style, blurring lines between art, commerce, and design. Yayoi Kusama collaborated with multiple fashion and consumer brands, bringing her infinity dots and pumpkin motifs to mass-produced goods.

These partnerships raise fundamental questions: Are corporations functioning as patrons supporting artists, or are artists lending credibility and cool factor to commercial brands? Does compensation for brand collaboration constitute patronage or simply commercial work?

Artists defend these relationships as modern patronage enabling their art practice. Critics see commercialization compromising artistic integrity. The truth likely varies case-by-case, but the prevalence of brand-artist collaborations indicates this will remain a significant patronage form.

Government Grants and Arts Councils

Government art funding represents institutionalized patronage replacing historical monarchies and aristocracies. The National Endowment for the Arts (U.S.), Arts Council England, and similar organizations in other countries distribute public funds to support artists.

This democratic patronage model—funding from taxpayers rather than wealthy elites—theoretically broadens access and reduces dependence on elite taste. Artists can receive grants based on artistic merit judged by panels rather than pleasing individual wealthy patrons.

However, government patronage creates its own constraints. Public accountability can lead to political interference, with controversial artists sometimes defunded after backlash. Government bureaucracy introduces application burdens and approval processes that favor artists with institutional literacy over raw talent. And limited budgets mean fierce competition for insufficient funds.

The grant system also changes artist behavior. Knowing what gets funded, artists may shape projects to match grant criteria rather than following pure artistic vision—different from historical patron control but constraint nonetheless.

The Dark Side of Patronage: Control, Censorship, and Compromise

Patronage history typically celebrates wealthy patrons who “made art possible” and artists who created masterpieces through generous support. But this narrative obscures troubling realities about power, control, and the price artists paid for financial security.

Patron Control Over Artistic Vision

Historical contracts reveal how completely patrons could control artistic output. Renaissance agreements specified not just subject matter but exact composition, figures’ positioning, color schemes, and innumerable details. Artists functioned more as skilled executors of patron vision than independent creators.

Isabella d’Este’s correspondence with artists she commissioned demonstrates micromanagement that would horrify modern artists. She sent detailed instructions about every element, demanded preliminary sketches for approval, and required changes if work deviated from her specifications. Her studiolo paintings reflect her vision more than the artists who painted them.

Even legendary artists lacked freedom we assume they possessed. Leonardo da Vinci worked under strict patron control. In his journal, Leonardo cryptically wrote: “The Medici made me, and the Medici destroyed me.” Scholars debate the exact meaning, but it likely referenced both enabling his career and constraining his vision. The families that funded Leonardo also limited what he could create.

Michelangelo, despite his towering reputation, abandoned the Medici Chapel project in 1534 when Duke Alessandro Medici’s patronage became unbearable. The most celebrated Renaissance artist literally fled his patron’s city. Even genius couldn’t fully escape patronage constraints.

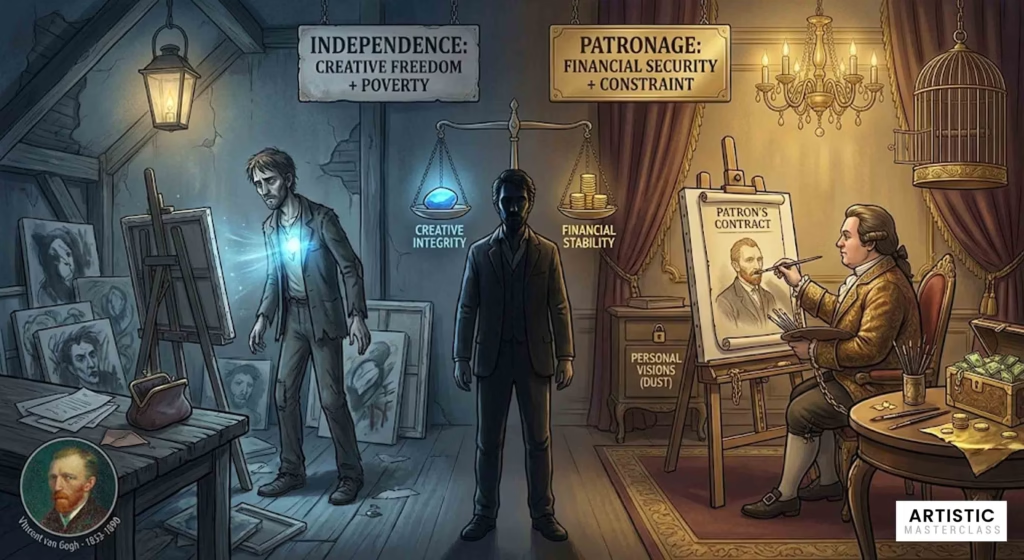

Economic Dependence and Artistic Freedom

Artists throughout history faced a cruel paradox: accepting patronage meant accepting control, but refusing patronage meant poverty and inability to create art at all. Expensive materials, time-intensive work, and lack of speculative markets (until the 19th century) made patronage economically necessary.

This dependence fundamentally shaped what art was created. Artists couldn’t pursue personal visions that wouldn’t attract patrons. Styles, subjects, and approaches that wealthy patrons found uninteresting simply never got made. We don’t know what Renaissance artists might have created if freed from patron specifications, because economic reality prevented such independent work.

Court artists exemplified total dependence. They received salaries and housing but had to create whatever their patron requested, from portrait paintings to festival decorations to military insignia designs. Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea Mantegna’s surviving letters contain repeated requests for overdue salary payments—even celebrated artists had to plead with tight-fisted patrons.

The “starving artist” trope emerged precisely when artists gained independence from patronage. Vincent van Gogh created over 2,000 artworks during his lifetime but died in poverty, having sold perhaps one painting. His tragedy illustrates both the freedom of working without patron constraints and the economic devastation of lacking patronage support.

Propaganda and Manipulation

Patronage frequently served propaganda purposes, with art functioning as tool for political manipulation and social control. Rulers from ancient Mesopotamia through Renaissance Italy commissioned art specifically to legitimize their authority and communicate their power.

Gudea’s statues glorified a relatively minor ruler, ensuring his remembrance through displays of wealth and piety. Renaissance patrons inserted themselves into religious scenes, equating their families with sacred history. Papal commissions projected spiritual authority while obscuring political machinations and moral compromises.

Religious patronage by the Catholic Church enforced doctrine and controlled populations. Art depicting proper behavior, divine punishment for sin, and Church authority shaped how millions understood Christianity. This wasn’t neutral cultural support—it was ideological indoctrination funded by the institution benefiting from those beliefs.

Artists working for propagandistic patrons faced moral choices. Create art serving patron’s potentially corrupt purposes and receive payment, or refuse and face economic consequences. Most chose survival and compromised.

The Price of Patronage

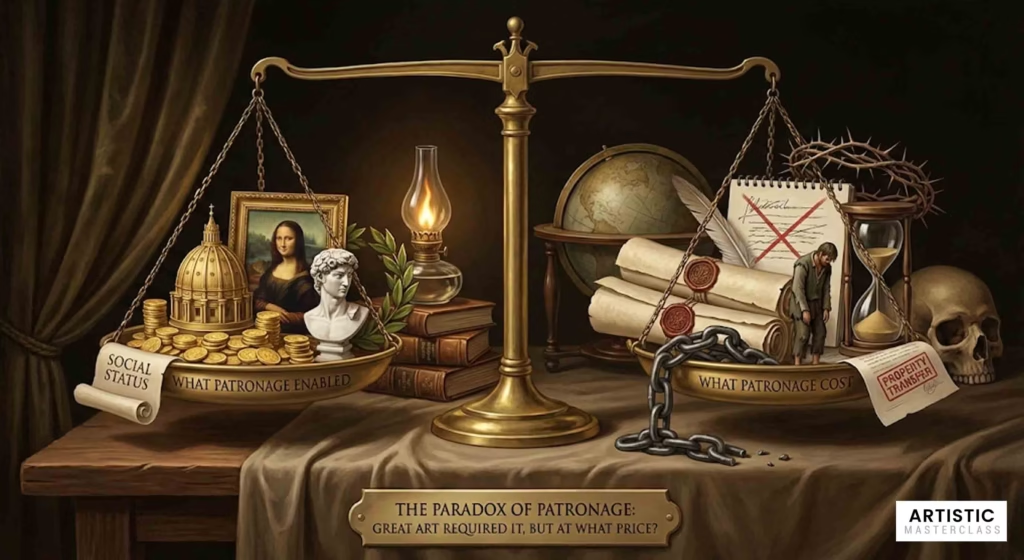

Assessing patronage requires acknowledging both what it enabled and what it cost.

What artists gained through patronage:

- Financial support enabling artistic careers

- Access to expensive materials impossible to afford independently

- Social status elevation (particularly during Renaissance)

- Protection from legal troubles and rival artists

- Opportunities to create ambitious large-scale works

- Reputation building through association with prestigious patrons

- Historical legacy through commissioned works that survived

What artists lost through patronage:

- Creative freedom to pursue personal artistic vision

- Ability to explore controversial subjects or styles

- Independence from patron specifications and micromanagement

- Rights to their own work (patrons owned commissions absolutely)

- Time spent on patron-required projects rather than personal interests

- Dignity when dealing with difficult, controlling, or abusive patrons

The balance varied by era, patron, and artist. Some Renaissance artists negotiated surprising freedom within patronage constraints. Others suffered greatly under oppressive patrons. But the fundamental power imbalance persisted: patrons held money, artists needed it, and that economic reality shaped artistic production for millennia.

Renaissance masterpieces exist because of patronage. The Sistine Chapel ceiling, Leonardo’s Last Supper, Raphael’s School of Athens—none would exist without wealthy patrons funding their creation. But we’ll never know what alternative artworks might have been created if artists possessed economic independence and creative freedom. Patronage both enabled and constrained artistic production, creating magnificent works while limiting artistic possibilities to what wealthy patrons would fund.

Frequently Asked Questions About Art Patronage

What’s the difference between an art patron and an art collector?

Art patrons commission the creation of new artworks, providing financial support during production and often specifying what should be created. Collectors acquire already-completed artworks, choosing from existing pieces rather than directing what gets made. Historically, patrons exercised significant control over artistic content and style, while collectors select from what artists have already independently created. Many wealthy individuals functioned as both patrons and collectors, but the relationships to artists differed fundamentally—patronage involves funding creation, collecting involves acquisition.

Did artists have creative freedom under patronage?

Creative freedom varied dramatically across eras and individual relationships. Renaissance artists worked under detailed contracts specifying subject matter, materials, composition, and countless other details, leaving limited creative freedom. Court artists had to create whatever patrons requested, from paintings to festival decorations. By the 19th century, some artists rejected patronage entirely to gain independence, though this often meant poverty. The most successful Renaissance artists like Michelangelo gradually earned more creative control through reputation, but even legendary artists faced restrictions from papal and aristocratic patrons. True artistic freedom is historically recent, emerging only as alternative income sources developed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

How were Renaissance artists paid?

Renaissance artists received payment through contractual agreements specifying total costs, advance payments, installments during production, and final payments upon completion. Contracts detailed everything from quality and quantity of expensive pigments (ultramarine blue cost more than gold) to completion deadlines. Court artists received regular salaries plus housing and sometimes land grants or tax exemptions. Payment could be delayed—Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea Mantegna’s surviving letters document battles over promised but unpaid wages. The most renowned artists commanded higher fees and better terms, but payment remained a constant negotiation and sometimes required legal action to enforce contracts.

Why did wealthy people commission art instead of making other luxury purchases?

Commissioned art served multiple purposes beyond simple luxury consumption. It demonstrated refined taste and classical education to peers, legitimized political authority through visual propaganda, displayed religious piety (and sometimes atoned for sins like usury), created family legacy ensuring remembrance after death, and provided conversation pieces demonstrating the patron’s knowledge of antiquity and current cultural trends. Art was simultaneously status symbol, political tool, religious expression, and investment in immortality. Wealthy patrons weren’t just buying beautiful objects—they were commissioning tangible manifestations of their power, taste, and importance.

What destroyed the traditional patronage system?

The traditional patronage system didn’t disappear but transformed fundamentally during the 19th century. The industrial revolution created broader wealth distribution, enabling a middle-class art-buying public. Artists began working speculatively (creating first, selling later) rather than only on commission. Art dealers and gallery systems emerged as intermediaries between artists and buyers. Independent artist exhibitions challenged academic and aristocratic gatekeepers. Public museums provided new exhibition venues independent of patron control. However, patronage adapted rather than vanished—20th century foundations, corporate sponsorship, government grants, and 21st century crowdfunding represent evolved patronage forms serving similar functions through different structures.

Were there female art patrons?

Yes, though women’s limited access to wealth and power made female patrons less common than male counterparts. Notable exceptions include Renaissance patron Isabella d’Este (Marchioness of Mantua) who commissioned Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and other masters; Catherine the Great (18th century Russia) who expanded the Hermitage Museum collection and supported numerous artists; Peggy Guggenheim (20th century) who launched Abstract Expressionism by supporting Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning; and Isabella Stewart Gardner (American Gilded Age) who built a museum for her extensive collection. These women shaped artistic careers and movements despite social constraints limiting female economic and cultural power.

How did patronage influence what styles were popular?

Patron preferences directly shaped artistic styles and movements. Renaissance patrons demanding classical references encouraged humanist aesthetics emphasizing perspective, proportion, and glorification of the human body. Royal patrons favoring dramatic display drove Baroque grandeur with emotional intensity and elaborate decoration. Academic patronage enforced traditional styles until independent exhibitions enabled Impressionism. Foundation patronage in the 20th century enabled experimental Abstract Expressionism that commercial galleries initially rejected. Throughout history, artists created what patrons would pay for, meaning patron taste determined which styles flourished and which languished. Artistic innovation required either wealthy avant-garde patrons willing to support experimental work or artists accepting poverty to pursue unpopular styles.

Did non-Western cultures have art patronage?

Absolutely. Art patronage emerged wherever wealth concentration and artistic production intersected, making it a universal human phenomenon across cultures. Islamic caliphates featured extensive patronage, with Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent commissioning manuscripts, jeweled vessels, silks, and painted ceramics. Chinese emperors ran court painting academies and controlled artistic production through imperial patronage. Japanese shoguns and daimyo supported artists, particularly related to Zen Buddhism and tea ceremony aesthetics. Indian Mughal courts maintained extensive workshops for miniature painting and architectural projects. African kingdoms like Benin supported bronze sculptors and court artists. Each culture developed unique patron-artist relationships reflecting political structures, religious beliefs, and aesthetic values, but the fundamental patronage dynamic remained recognizable across civilizations.

What happens when patrons and artists disagreed?

Conflicts between patrons and artists led to litigation, destroyed artworks, abandoned projects, and severed relationships. Diego Rivera’s 1932 Rockefeller Center mural was destroyed when Rivera added Vladimir Lenin against patron wishes, demonstrating economic power trumping artistic vision. Michelangelo abandoned the Medici Chapel project in 1534 when Duke Alessandro Medici’s patronage became unbearable, fleeing Florence for Rome. Renaissance contracts included legal provisions allowing patrons to sue for inadequate work and artists to sue for non-payment—litigation wasn’t uncommon. Artists with established reputations could navigate conflicts better by finding alternative patrons, but emerging artists dependent on single patrons had to accept patron demands or face career devastation. The fundamental power imbalance meant patrons usually won disputes.

Is modern crowdfunding really patronage?

Yes, crowdfunding represents democratized patronage with similar economic functions but dramatically different power dynamics. Historical patronage concentrated power in wealthy individuals who commissioned specific works and often dictated content. Crowdfunding distributes patronage across many supporters providing small contributions, enabling artist-chosen projects rather than patron-specified works. Patreon explicitly references historical patronage models, providing artists recurring income similar to Renaissance court artists’ salaries. The core economic function remains identical—funding artistic production that wouldn’t otherwise occur—but power shifts toward artist autonomy because no single patron controls funding. This makes crowdfunding simultaneously more democratic (broader participation) and more artist-directed (less patron control) than traditional patronage while serving fundamentally similar purposes.

Key Takeaways: What 4,000 Years of Patronage Teaches Us

Looking across four millennia of art patronage, from Gudea’s diorite statues through Renaissance masterpieces to contemporary crowdfunding, several profound truths emerge about the relationship between wealth, power, and artistic creation.

Art production has always required external funding. This isn’t merely historical accident but economic necessity. Expensive materials, time-intensive work, and specialized skills meant artists couldn’t self-fund their practice. From ancient Mesopotamia through the 20th century, most significant artworks existed only because wealthy individuals, institutions, or governments provided resources. Patronage wasn’t optional—it was the economic engine of artistic production.

Patronage was fundamentally about power, not altruism. While some patrons genuinely loved art, commissioning expensive artworks primarily served to demonstrate authority, legitimize political positions, display refined taste, ensure religious piety, and create lasting legacies. Art functioned as propaganda tool and status symbol simultaneously. Renaissance patrons commissioned religious scenes featuring their own portraits, ancient rulers covered temples with their likenesses, popes used art to justify controversial reigns. The beauty we admire often disguised calculated power moves.

The patron-artist relationship was structurally unequal. Despite Renaissance elevation of artists to intellectual status, patrons controlled commissions, specified content, censored displeasure, and sometimes destroyed works. Artists gained creative freedom slowly, over centuries, through hard-won reputation building. Even Michelangelo and Leonardo worked under significant constraints. The romantic myth of the independent artist creating purely personal vision is historically recent, emerging only as alternative income sources developed in the 19th century.

Patronage shaped artistic movements and aesthetics. Renaissance humanism, Baroque grandeur, Impressionist innovation, Abstract Expressionism—all emerged from specific patronage structures determining what got funded. Patron preferences dictated subject matter, style, scale, and technique. Artists created what patrons would pay for, meaning market dynamics determined aesthetics as much as artistic vision. We see the art that wealthy patrons chose to fund; alternative artistic possibilities that lacked patron support simply never manifested.

Artist independence is historically anomalous. For over 4,000 years, artists worked primarily on commission, creating what patrons specified. The 19th century idea of artists creating personal vision first, then finding buyers represented radical transformation lasting barely two centuries. Even today, most artists balance patronage relationships (grants, commissions, sponsorships) with independent work. The completely autonomous artist is largely mythological—economic reality requires external funding sources.

Patronage adapted rather than disappearing. While aristocratic and ecclesiastical monopolies ended, patronage evolved into foundations, corporate sponsorship, government grants, and crowdfunding. The Guggenheim Foundation functions similarly to Medici patronage, supporting avant-garde work that lacks commercial viability. Patreon is digital-age patronage with democratized power distribution. Corporate brand partnerships continue ancient patterns of wealthy entities funding art serving their interests. The fundamental structure persists: those with resources supporting those creating culture.

Control was patronage’s hidden cost. Artists gained materials, income, social status, and opportunities to create ambitious works—but surrendered creative freedom, personal vision, and artistic integrity. Renaissance masterpieces exist because patronage enabled their creation. But we’ll never know what alternative artworks artists might have created with economic independence and complete creative control. Every commissioned masterpiece represents roads not taken, visions unrealized, possibilities constrained by patron preferences.

Final Reflection

Art history isn’t merely the story of genius artists creating masterpieces through inspiration and talent. It’s equally the story of who held economic power, who decided what art deserved funding, and what messages wealthy patrons wanted communicated through commissioned works.

Every masterpiece carries invisible fingerprints of the patron who commissioned it, shaped its content, approved its execution, and sometimes controlled its meaning. Understanding patronage means recognizing that art has always been about money, power, and the complex negotiations between creativity and constraint, vision and control, genius and commerce.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling is simultaneously Michelangelo’s artistic triumph and Pope Julius II’s propaganda project. Leonardo’s Last Supper demonstrates revolutionary artistic technique within the constraints of Ludovico Sforza’s commission. Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings express personal artistic vision made possible by Peggy Guggenheim’s financial support and museum platform.

None of this diminishes artistic achievement. Understanding patronage’s role deepens appreciation for how artists navigated constraints, negotiated with power, and sometimes created transcendent works despite limitations. It also reminds us that art exists within economic and political systems, shaped by who holds resources and decides what deserves support.

As contemporary patronage evolves through crowdfunding, NFTs, corporate partnerships, and government grants, the fundamental questions persist: Who decides what art gets made? How do economic relationships shape creative vision? What balance between support and control best serves artistic excellence? After 4,000 years, we’re still negotiating these tensions, still seeking systems that enable great art while respecting artistic freedom.

The story of art patronage is the story of human civilization itself—our values, power structures, and beliefs about what matters made tangible through funded artistic creation. Understanding this history helps us recognize how profoundly economic systems shape cultural production, and perhaps imagine more equitable futures for supporting human creativity.