Introduction to Art History and Its Significance

Art history is more than a chronicle of paintings and sculptures – it’s a window into the evolution of human culture and creativity. Spanning tens of thousands of years, the evolution of art integrates history, sociology, archaeology, and even philosophy to provide a holistic understanding of artworks within the societies that produced them.

Each major art movement emerged with distinct styles and techniques that reflected the social and political influences of its era.

For example, Renaissance art’s focus on humanism mirrored the era’s intellectual revival, while Impressionism in the 19th century broke academic rules in favor of capturing fleeting moments of modern life.

Whether you’re an aspiring collector, a curator, or simply an art enthusiast, studying these major movements is a worthwhile endeavor.

Many contemporary artists (from Banksy to Kehinde Wiley) infuse historical art references into their works, so understanding the context of each period is critical for appreciating art’s ongoing dialogue.

In this overview, we’ll travel chronologically through the evolution of art and its major movements – from prehistoric cave paintings to today’s contemporary trends – highlighting each period’s key characteristics, influential artists, and lasting impact on the art world.

Prehistoric Art (c. 40,000–4,000 B.C.): The Dawn of Creativity

Prehistoric cave paintings in Lascaux, France (c. 17,000 years old) depict animals like bulls and horses, using natural pigments on rock walls

These Paleolithic images are among the earliest expressions of human creativity.

The origins of art history trace back to the Prehistoric era, long before written records

Early humans created rock carvings, pictorial cave paintings, stone arrangements, and small sculptures using natural pigments and materials

Much of this art had ritual or survival-related significance – depicting animals, hunting scenes, and symbols believed to hold mystical power over nature or to record important events.

A famous example is the cave paintings at Lascaux in France, discovered in 1940. These detailed images of bulls, horses, and deer are estimated to be up to 20,000 years old

The artists applied mineral-based colors to the cave walls, achieving surprisingly dynamic and expressive forms. Likewise, prehistoric sculptors carved small figurines like the Venus of Willendorf (c. 25,000 B.C.), a tiny stone figure thought to represent fertility. Although the creators of prehistoric art remain unknown, their works mark humanity’s first attempts at visual storytelling and symbol-making.

Key Characteristics: Prehistoric art is characterized by its use of natural materials (charcoal, earth pigments, stone) and themes centered on animals, humans, and abstract signs. Art served practical and spiritual purposes – possibly used in rituals or as teachings for survival. These earliest artworks laid the foundation for all subsequent art, proving that the impulse to create and communicate visually is deeply rooted in human nature.

Ancient Art (c. 4000 B.C.–A.D. 400): Civilizations and Mythologies

With the rise of ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Aegean, and the Americas came more advanced forms of art. Ancient art was produced by societies that had developed writing, cities, and organized religion

Art became a tool to tell stories of gods and heroes, decorate utilitarian objects, signify power, and honor the deceased. Common media included carved stone reliefs, statues, pottery, and wall paintings.

In Mesopotamia, for instance, artisans created the Code of Hammurabi stele (c. 1750 B.C.), inscribing laws in stone beneath an image of King Hammurabi receiving authority from a god.

Ancient Egyptian art, famously exemplified by the painted tombs and monumental Pyramids at Giza, adhered to strict conventions meant to ensure order and continuity. Figures were depicted in composite poses (heads in profile, torsos frontally) and tomb paintings illustrated scenes for the afterlife – from offering rituals to mythical journeys.

Greek and Roman art introduced naturalism and idealized human forms. Classical Greek sculptors like Phidias and Polykleitos sought perfect proportion in statues of gods and athletes, pioneering anatomical realism. The Greeks also built enduring architectural marvels (the Parthenon’s sculpted friezes, for example). The Romans, inheriting Greek traditions, excelled in portrait sculpture and engineering feats like the Colosseum. They often copied Greek models but also developed a talent for realistic busts and expansive narrative reliefs (such as Trajan’s Column).

Key Artists/Cultures: Rather than individual artists, ancient art is usually attributed to cultures or workshops. Notable contributions include Mesopotamian ziggurats and reliefs, Egyptian pharaoh portraits (King Tut’s golden mask), the Greek vase painters and sculptors, and Roman architects and mosaicists.

Influence: Ancient art established many themes and forms that echo through history – from the use of art for storytelling and commemoration to the pursuit of ideal beauty. Later Renaissance artists would be directly inspired by Greco-Roman sculpture and mythology. Museums today are filled with ancient artifacts, and curators often contextualize contemporary works alongside these archetypes to draw connections across millennia.

Medieval Art (A.D. 500–1400): Faith and Artistry in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Europe – often called the “Dark Ages” for its early period of turmoil – saw art primarily in the service of religion. After the fall of Rome (5th century), economic and cultural decline meant art became more primitive and otherworldly, focusing on Christian themes amid a landscape of war and plague

Early medieval art (c. 500–1000) includes the intertwined animal motifs of Migration-period metalwork, the flat and symbolic mosaics of Byzantine churches, and illuminated gospel manuscripts by monastic scribes.

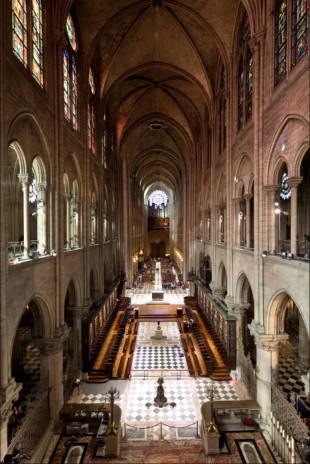

As stability slowly returned, medieval art grew more sophisticated. The Romanesque style (c. 1000–1150) revived large-scale stone architecture – thick-walled churches with frescoed interiors and relief carvings of biblical stories. By the Gothic period (c. 1150–1400), builders like Abbot Suger of St. Denis introduced soaring cathedrals with pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and stained glass windows that flooded interiors with mystical light

Gothic cathedrals such as Notre-Dame de Paris remain masterpieces of art and engineering, adorned with sculpted façades and thousands of stained glass images teaching the Bible to an illiterate populace.

Painting in the Middle Ages was largely devotional. Icons and altar pieces presented stylized holy figures against gold backgrounds, emphasizing spiritual concepts over naturalism. Not until the 14th century did artists like Giotto di Bondone begin to reintroduce natural observation – shading figures to appear three-dimensional and staging emotional biblical scenes (e.g. Lamentation of Christ) that paved the way for the Renaissance.

Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ)

Ognissanti Madonna

Key Characteristics: Medieval art is devotional and didactic – meant to inspire faith and convey religious narratives. Common forms include illuminated manuscripts (hand-painted holy books like the Lindisfarne Gospels, mosaics (as in Ravenna or Constantinople), fresco paintings, and sculptures integrated into architecture (capitals, doorways, tombs). The style evolved from abstract and otherworldly to increasingly naturalistic by the Gothic era.

Legacy: Medieval artisans developed techniques (stained glass, manuscript illumination, tapestry weaving) that are treasured crafts today. The era’s focus on spiritual expression influenced later movements like the Pre-Raphaelites in the 19th century. For collectors and curators, medieval art offers insight into the fusion of art and faith – understanding this context enriches one’s appreciation of any religious or fantastical imagery in art that followed.

Renaissance Art (1400–1600): Rebirth of Classical Ideals

The Renaissance was a revolutionary period in art, originating in 15th-century Italy and soon spreading across Europe. Renaissance artists looked back to the classical antiquity of Greece and Rome for inspiration, embracing humanism – the celebration of human intellect and beauty – and developing new artistic techniques to mirror nature with astonishing realism

This era saw an explosion of masterworks in painting, sculpture, and architecture that remain benchmarks of artistic achievement.

Characteristics: Renaissance art is defined by its realism, balance, and attention to detail

Artists studied anatomy to portray the human body accurately and beautifully. They pioneered the use of linear perspective (invented by Filippo Brunelleschi) to create convincing depth on flat surfaces, and they mastered chiaroscuro (light and shadow) to model forms in three dimensions. Compositions were often harmonious and symmetrical, reflecting classical ideals of order.

High Renaissance (c. 1490–1527) in Italy brought forth giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raphael Sanzio, who collectively pushed art to new heights.

Lady with an Ermine – Painrting by Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and The Last Supper showcase his sfumato technique (subtle blending of tones) and psychological depth. Michelangelo’s sculptural genius produced the marble David (1504) – a pinnacle of anatomical perfection – and his Sistine Chapel frescos exemplify heroic human figures with dynamic poses. Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens (1511) epitomizes the Renaissance spirit, depicting ancient philosophers in a grand, perspective-perfect architectural setting, embodying the union of art, knowledge, and harmony

Sistine Chapel

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509–1511) exemplifies High Renaissance ideals – balancing a complex composition of figures within a perfectly perspectival space. Classical philosophers like Plato and Aristotle are depicted with lifelike form and calm grandeur, reflecting the era’s humanist reverence for antiquity and knowledge

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509–1511)

Outside Italy, the Northern Renaissance flourished in Flanders, Germany, and elsewhere, where artists like Jan van Eyck and Albrecht Dürer combined newfound realism with Late Gothic detail. Van Eyck’s oil paintings, for example, achieved microscopic precision and rich color (as in the Arnolfini Portrait). In all regions, Renaissance art signified a rebirth (renaissance) of creativity grounded in observation of the natural world and the rediscovery of classical wisdom.

Arnolfini Portrait – Artowrk by Jan van Eyck

Key Artists: Italy: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Donatello (sculpture), Botticelli, Titian. Northern Europe: Jan van Eyck, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein. Their works range from religious scenes reimagined with human emotion to mythological subjects and secular portraiture of unprecedented realism.

Impact: The Renaissance set the standards of artistic skill and intellectual depth that artists still aspire to. Techniques like perspective and realistic figure drawing became core foundations of Western art training. For contemporary curators, Renaissance works are often centerpieces of museum collections, and understanding their context – from the Medici patronage in Florence

to the scientific inquiries of Leonardo – allows for richer interpretation. Many modern artworks pay homage to Renaissance masterpieces or concepts, making knowledge of this period invaluable for appreciating art’s ongoing dialogue.

Baroque Art (1600–1750): Drama and Grandeur

The Baroque era followed the Renaissance and Mannerist periods, emerging around 1600. If the Renaissance was about balance and clarity, Baroque art was about emotion, movement, and sensory richness. Baroque artists sought to awe viewers and draw them into the scene – a goal aligned with the Counter-Reformation spirit (the Catholic Church’s use of art to inspire faith) and absolute monarchies seeking to display power.

Characteristics: Baroque art is ornate, dynamic, and theatrical.

Compositions swirl with energy; figures often spiral or extend beyond the frame. Strong contrasts of light and dark (tenebrism) heighten drama, as pioneered by Caravaggio’s intense lighting in painting.

Architecture and interior design from this period are similarly lavish – think gilded altarpieces, twisting Solomonic columns, and expansive fresco ceilings that dissolve the boundary between art and reality.

Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (c.1599)

In painting, Caravaggio of Italy and Rembrandt of the Netherlands exemplify Baroque mastery of light. Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (c.1599) uses a beam of light cutting through shadow to illuminate a mundane tavern scene where Christ summons a tax collector – the spiritual moment is rendered with startling, gritty realism and dramatic focus.

Rembrandt’s portraits and scenes, like The Night Watch (1642), similarly use chiaroscuro and rich, earthy colors to create mood and depth, while also exploring profound human emotion.

The Night Watch (1642) – Artwork by Rembrandt

The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600) showcases Baroque drama with its use of high contrast lighting (chiaroscuro) and realistic figures. The beam of light picking out the surprised Matthew and his companions amid a dark tavern exemplifies Baroque art’s theatrical energy and focus on telling a story in a single, intense moment

Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1652) – Sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Baroque sculpture reached new heights of motion and emotion in the hands of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. His Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1652) in Rome captures a swooning saint and a smiling angel in marble, so animated it seems to breathe with spiritual rapture. In architecture, Baroque produced grand palaces and churches – St. Peter’s Basilica was completed with a Baroque façade and piazza by Bernini, and Versailles in France (though more Classical in design) is opulent in the Baroque spirit of absolutist spectacle.

St. Peter’s Basilica’s piazza and fittings by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Key Artists: Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens (known for energetic compositions and voluptuous figures in motion), Diego Velázquez (master of optical realism in Spain), Bernini (sculpture and architecture), and architects like Francesco Borromini (with his bold, curving church designs in Rome).

Legacy: Baroque art’s embrace of viewer engagement and emotional storytelling has influenced everything from 19th-century Romantic painting to modern cinema. Many contemporary artists and exhibit designers draw on Baroque techniques – such as dramatic lighting or immersive installation – to captivate audiences. For collectors, Baroque paintings and furnishings represent luxury and intensity; understanding their historical context (the patronage of popes and kings, the religious strife of the 17th century) adds depth to their appreciation

Rococo (c. 1700–1780): Lightness and Whimsy in Art

In the early 18th century, the Baroque’s grandeur gave way in some regions to the lighter, more playful style of the Rococo. Centered in France during the reign of Louis XV, Rococo art and design were all about elegance, flirtation, and decorative beauty – perfectly suited to the refined salons of the aristocracy. Rococo can be seen as the final flourish of the Baroque era, softer in tone and more focused on leisure and love.

Characteristics: Rococo art is ornamental, pastel-colored, and often frothy in tone.

Paintings featured romantic pastoral scenes, fêtes galantes (outdoor amusements of the upper class), and mythological love stories, rendered with delicate brushwork and an airy atmosphere. The compositions are asymmetrical and full of curving forms (mirroring the era’s serpentine furniture designs and elaborate stucco scrollwork in interiors)

The Embarkation for Cythera (1717) – Artwork by Antoine Watteau

Antoine Watteau and François Boucher were leading Rococo painters. Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera (1717) exemplifies the style: couples in silks and satins gather in a dreamy landscape, bidding farewell to the mythical island of love – the scene is tender, gently melancholic, and bathed in soft light.

Boreas Abducting Oreithyia,, 1769 – Artwork by François Boucher

Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard took Rococo frivolity further with sensuous scenes (Fragonard’s The Swing, 1767, scandalously shows a lady kicking off her shoe mid-air while a lover peeks up her skirt). In decor, Rococo brought about gilt-encrusted furniture with asymmetrical shell and floral motifs, porcelain figurines, and intricate tapestries, all meant to create an intimate, luxurious ambienceThe

The Swing (1767) – Artwork by Jean-Honoré Fragonard

Key Artists/Designers: In addition to Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard, sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet crafted dainty porcelain and marble pieces, and interior designers like Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier shaped Rococo’s hallmark look in wall panels and furnishings.

Transition: By the late 18th century, Rococo’s lighthearted extravagance fell out of favor amid calls for a return to moral seriousness – in part due to the Enlightenment and events like the French Revolution. This pendulum swing led to the next major movement, Neoclassicism, which rejected Rococo’s “frivolity” in favor of classical restraint and virtuous themes.

Neoclassicism (c. 1750–1850): Return to Classical Simplicity

Neoclassicism was a broad movement in art and architecture that sought to revive the spirit and forms of classical antiquity. Spurred by archaeological discoveries (such as Pompeii’s excavation in 1748) and the Enlightenment’s admiration of Ancient Greece and Rome, Neoclassical art stood in stark contrast to the Rococo style that preceded it

This was the art of revolutions and new republics – conveying virtues like liberty, patriotism, and stoic heroism through classical imagery.

Characteristics: Neoclassical art is orderly, stoic, and inspired by classical forms.

Paintings often feature clean lines, sculptural figures in Roman dress, and compositions arranged like a bas-relief frieze. The color palette tends toward cooler or more restrained tones compared to Baroque/Rococo richness. Subjects are drawn from ancient history or mythology, used allegorically to comment on contemporary moral ideals (e.g., courage, sacrifice, civic duty).

Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784)

A quintessential Neoclassical work is Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784), in which three brothers swear an oath to Rome, their muscular forms starkly lit against a severe architectural backdrop – a call to duty and unity that resonated on the eve of the French Revolution.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) – Artwork by Jacques-Louis David

David’s later Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) presents the modern leader in classical hero mode, calm on a rearing horse (even if in reality Napoleon crossed on a mule).

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787) – Sculpture by Antonio Canova

In sculpture, Antonio Canova was a leading Neoclassicist: his marble figures, like Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787), echo Greek ideals of beauty and grace, yet with a modern softness that avoids the “cold artificiality” sometimes found in earlier classical imitations

Architecture of this period also embraced symmetry and grand simplicity – think of the Panthéon in Paris or the Capitol in Washington, D.C., with their temple fronts and domes modeled on Roman design. These structures symbolized democratic and rational principles by literally building on classical foundations.

Key Artists: Jacques-Louis David dominated French painting, mentoring others like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who carried the Neoclassical style into the 19th century with his exquisitely drawn figures. In Britain, Angelica Kauffman and Benjamin West painted classical and historical scenes, while architects like Robert Adam designed Neoclassical buildings and interiors.

Self Portrait – Artwork by Angelica Kauffman

Influence: Neoclassicism reinforced the link between art and civic ideals. It influenced everything from the fine arts to furniture design (e.g., Thomas Sheraton’s simple, classical furniture in England). For today’s viewers, Neoclassical art provides insight into the mindset of the Enlightenment and revolutionary eras – curators often pair these works with historical documents or propaganda of the time to highlight art’s role in shaping political narratives

Romanticism (c. 1780–1850): Emotion and Nature Unleashed

Running parallel to late Neoclassicism – and often in reaction to it – Romanticism arose in the late 18th century as a celebration of emotion, imagination, and the sublime forces of nature. Where Neoclassicists valued reason and order, Romantics valued individual feeling and the awe of the natural world.

This movement spanned literature, music, and the visual arts, producing works that were dramatic, moody, and often filled with movement.

Characteristics: Romantic art is passionate, adventurous, and often melancholy. It rejects the cool rationality and restrained compositions of Neoclassicism.

Instead, Romantic painters favored turbulent scenes – shipwrecks, raging storms, dramatic landscapes at sunset – or explored intense human experiences like madness, nightmarish visions, and exotic cultures. Brushwork became looser and more expressive, color more vivid or contrast heightened to convey feeling. Crucially, many Romantics turned to plein air painting (working outdoors) to capture natural light and atmosphere directly, which later influenced the Impressionists.

Liberty Leading the People (1830) – Artwork by Eugène Delacroix

In France, Eugène Delacroix led the Romantic school with vibrant, energetic canvases such as Liberty Leading the People (1830), where a personified Liberty strides over barricades during the 1830 revolution, tricolor flag in hand – a scene of chaos elevated to poetic symbolism by rich color and dynamic composition.

Rain, Steam and Speed, (1844) – Artwork by J.M.W. Turner

In England, J.M.W. Turner painted luminous landscapes and seascapes (Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844) that verge on abstraction, using swirls of paint to suggest light and motion, evoking the smallness of man against nature’s power.

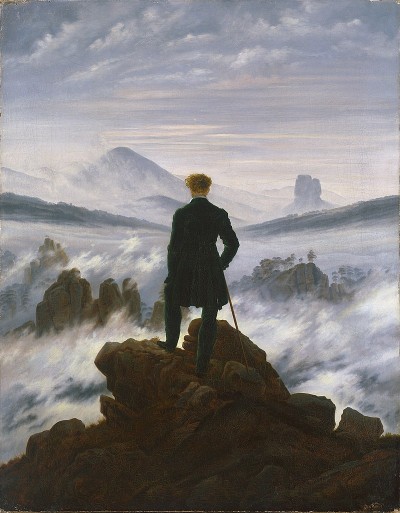

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c.1818) – Artwork by Caspar David Friedrich

German painter Caspar David Friedrich exemplified the introspective side of Romanticism: his Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c.1818) shows a lone figure from behind, perched on a rocky summit, contemplating a foggy expanse – a visualization of the Romantic ideal of the sublime, where beauty and terror in nature inspire spiritual reflection.

Key Artists: Besides Delacroix, Turner, and Friedrich, other notable Romantics include Francisco Goya in Spain, whose later works (like The Third of May 1808, 1814, depicting war’s horrors) are profoundly emotional and critical;

The Third of May (1808) – Artwork by Francisco Goya

Théodore Géricault, painter of The Raft of the Medusa (1819), a gruesome shipwreck scene turned indictment of governmental negligence; and William Blake in Britain, who as both poet and painter created mystical images rich with symbolism. Romanticism was broad, even encompassing Henry Fuseli and William Blake who painted the supernatural and macabre, probing the dark recesses of the human psyche

The Raft of the Medusa (1819) – Artwork by Théodore Géricault

Legacy: Romanticism expanded the subject matter of art to include the personal, the fantastical, and the natural in its wild state – paving the way for later movements like Symbolism and Expressionism. It taught that art could be a vehicle for social critique and personal expression, not just depiction. Contemporary audiences often find Romantic paintings relatable for their emotional honesty and emphasis on individual perspective. Curators today might draw parallels between Romantic artists and modern ones who similarly prioritize personal voice or address the human relationship with nature (for instance, environmental art). Romantic works continue to remind collectors and viewers of the enduring power of emotion and imagination in art’s narrative.

Realism (c. 1848–1900): The Gritty Truth of Modern Life

By the mid-19th century, in an age of industrial revolution and social change, a new movement emerged that pointedly broke from the idealized subjects of Romanticism: Realism. Realist artists sought to depict everyday life and ordinary people with truth and accuracy, even at the expense of prettiness or drama.

In doing so, they laid the groundwork for modern art’s focus on contemporary scenes and genuine narratives.

Characteristics: Realism in art is unvarnished and democratic. Realist painters turned their attention to peasants, workers, and domestic life, portraying them on the same scale and seriousness previously reserved for heroes and gods. They often painted directly from life, with an almost journalistic eye, influenced by the advent of photography and the rise of the press

The colors and tones tend to be earthy and muted, matching the ordinary settings; compositions can be straightforward, sometimes even blunt, without the melodrama of Romantic works.

In France, Gustave Courbet was the leading Realist. His manifesto-like statement, “I cannot paint an angel because I have never seen one,” summarizes the Realist ethos. Courbet’s paintings such as The Stone Breakers (1849) showed laborers toiling with heavy rocks, and A Burial at Ornans (1850) depicted a country funeral not of famous figures but of a common villager – these canvases were shockingly large for such humble subject matter, forcing viewers (and the art establishment) to confront the dignity and struggle of ordinary existence

The Stone Breakers (1849) – Artwork by Gustave Courbet

A Burial at Ornans (1850) – Artwork by Gustave Courbet

In a similar vein, Jean-François Millet painted rural workers with empathy (e.g. The Gleaners, 1857), showing peasant women collecting leftover grain in the fields, and the Barbizon School artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot focused on naturalistic landscapes without idealization.

The Gleaners, 1857 – Artwork by Jean Francois Millet

Realism also flourished beyond France: In Russia, the Peredvizhniki (“Wanderers”) like Ilya Repin portrayed social realities; in the U.S., Winslow Homer captured scenes of Civil War and life on the American coast with unsentimental clarity.

Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm – Artwork by Ilya Repin

Rest (1885) – Artwork by Winslow Homer

Influence on later art: By insisting on the present as worthy of depiction, Realists set the stage for the Impressionists and subsequent modern movements to take art further out of the academy and into the streets and countryside. They also embraced new media – the influence of photography is evident, as Realists often composed scenes as if cropped from real life, a concept that later movements (Impressionism, Ashcan School) expanded on

For collectors and curators today, Realist works offer a valuable historical document of 19th-century life and an aesthetic of sincerity. Understanding Realism helps one appreciate how revolutionary it was to paint “mundane” reality – a revolution that continues every time an artist chooses truth over idealization in their work.

Impressionism (c. 1865–1885): Capturing the Fleeting Moment

By the 1860s, Paris was the epicenter of a new artistic rebellion. A group of young artists – later known as the Impressionists – took Realism’s focus on modern life and married it to an obsession with light and color. They painted rapidly, often outdoors, aiming to capture the momentary “impression” of a scene rather than a detailed academic rendering.

Initially ridiculed by critics (the term “Impressionist” itself came from a sarcastic review), the movement soon revolutionized painting and profoundly influenced the course of modern art.

Characteristics: Impressionist paintings are bright, loosely brushed, and plein-air. Instead of smooth blending, Impressionists use visible, broken brushstrokes that optically blend at a distance.

This technique conveys a sense of movement and spontaneity – as if the image is alive and changing before your eyes. They favored contemporary subjects: leisurely outings, city streets, ballet rehearsals, boating on the river – scenes of modern bourgeois life in the city and countryside.

Crucially, Impressionists were fascinated by how light at different times of day or weather conditions alters the appearance of color. Thus, they painted the same subject in series under different lighting (Monet famously painted haystacks and the Rouen Cathedral at various times to study changes in color and atmosphere).

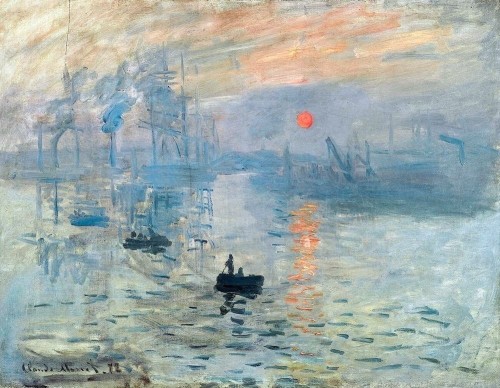

Claude Monet is virtually synonymous with Impressionism. His painting Impression, Sunrise (1872) – depicting a hazy dawn over the harbor of Le Havre with quick strokes and dabs of orange sunlight on rippling water – gave the movement its name

Impression, Sunrise (1872) – Artwork by Claude Monet

Monet and his peers exhibited independently from the official Salon, marking a break from institutional control. Other core Impressionists include Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who delighted in scenes of social pleasure like dancing at a café (Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, 1876, is a sun-dappled snapshot of Parisian nightlife)

Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, 1876 – Artwork by Pierre Auguste Renoir

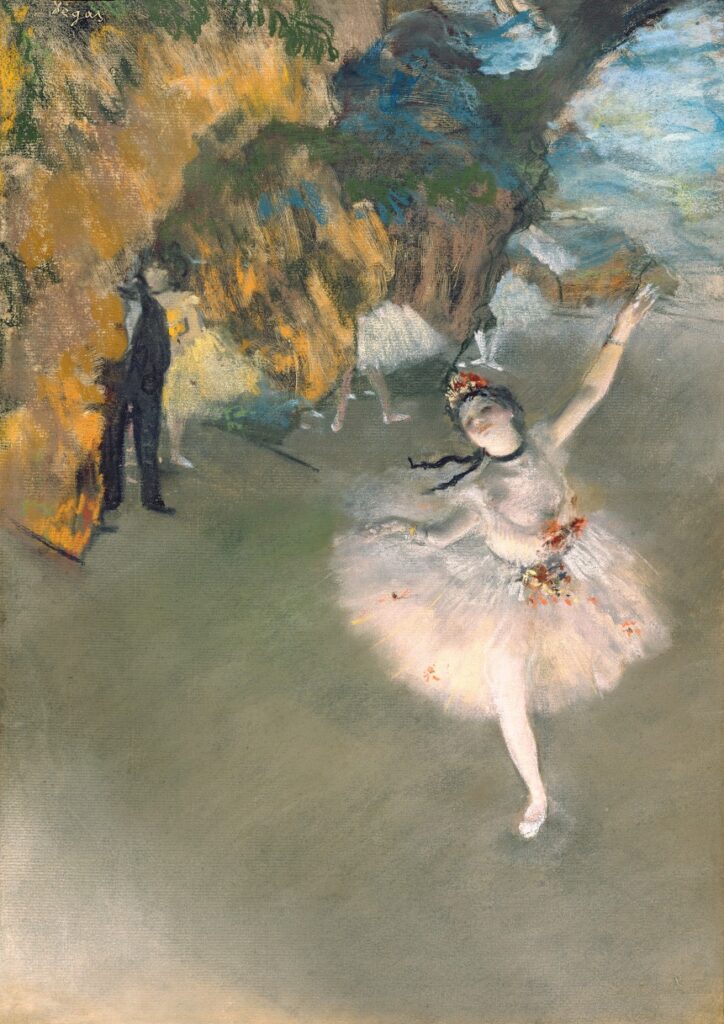

Edgar Degas, known for candid compositions of ballet dancers and horse races (often from unusual angles, influenced by photography and Japanese prints), and Camille Pissarro, who painted both rural labor and urban cityscapes with equal vigor.

The Star (1878) – Artwork by Edgar Degas

Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) – the painting that inspired the term “Impressionism” – uses loose, rapid brushstrokes and luminous color to capture a fleeting sunrise over water

The goal was not detail, but to convey the sensation of that exact moment in time, a radical shift from the polished realism of earlier art.

Importantly, Impressionism expanded the palette – shadows could be violet or blue (not just gray or black), and pure unmixed pigments gave paintings a vibrant, high-key effect. The Impressionists’ approach to composition was also novel: influenced by the casual framing of photography and Japanese ukiyo-e prints, they often cropped figures or shifted perspectives in ways that felt spontaneous and true to how we perceive glimpses of life.

Reception and Influence: Initially criticized for looking unfinished or “blurry,” Impressionist art soon won praise for its freshness. By capturing impressions of modern life, the movement inadvertently documented the fleeting, changing nature of the 19th-century world (Haussmann’s newly built Paris boulevards, for example, or the transient effects of light and weather). Future movements like Pointillism and Fauvism built on Impressionist color theories, while others like Post-Impressionists pushed back against its focus on the immediate visual impression.

For collectors, original Impressionist works are among the most prized (and priced) artworks, celebrated for their pioneering spirit and universal appeal. Curators often highlight how Impressionists paved the way for the avant-garde – breaking the dominance of the Salon and encouraging artists to explore personal vision. The movement’s legacy is also practical: today’s emphasis on painting from life and using color expressively owes much to these innovators.

Post-Impressionism (c. 1885–1910): Beyond the Impressionist Gaze

The term Post-Impressionism encompasses a diverse group of artists in the late 19th century who followed Impressionism but sought to inject greater emotion, structure, or symbolism into their work. While Impressionists focused on capturing optical sensations, Post-Impressionists were more interested in conveying subjective experiences and abstract truths through art.

This “movement” was not a unified one – it is a catch-all for several distinct styles – but its practitioners collectively laid groundwork for many 20th-century developments.

Characteristics: Since Post-Impressionists varied in approach, it’s easier to think of them in subsets:

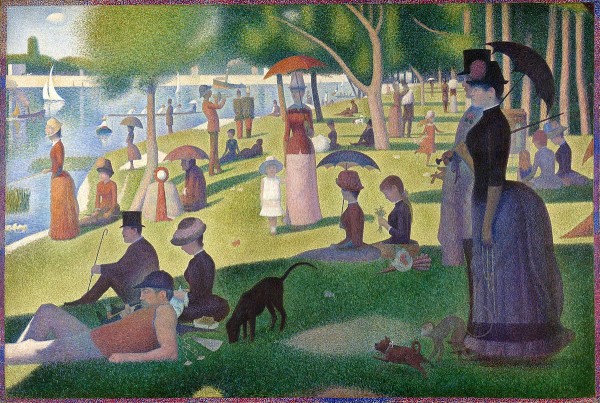

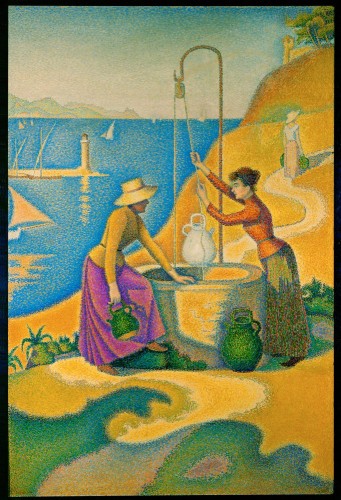

Some, like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, took a scientific approach to color. They developed Pointillism (or Divisionism), painting with tiny dots of pure color that fuse in the eye of the viewer. Seurat’s masterpiece A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86) is composed of countless points of pigment, achieving a luminous, stable quality that contrasted with the fluidity of Impressionism.

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86) – Painting by Georges Seurat

Women at the Well (1892) – Painting by Paul Signac

Others, like Paul Cézanne, sought to restore a sense of order and form. Cézanne used repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes and shifted perspective to portray the underlying geometry of nature (famously calling the cylinder, sphere, and cone the basis of all forms). His later works, like the Mont Sainte-Victoire series, flatten depth and fragment the view into facets of color – directly influencing the rise of Cubism.

Mont Sainte-Victoire series – Artwork by Paul Cezanne

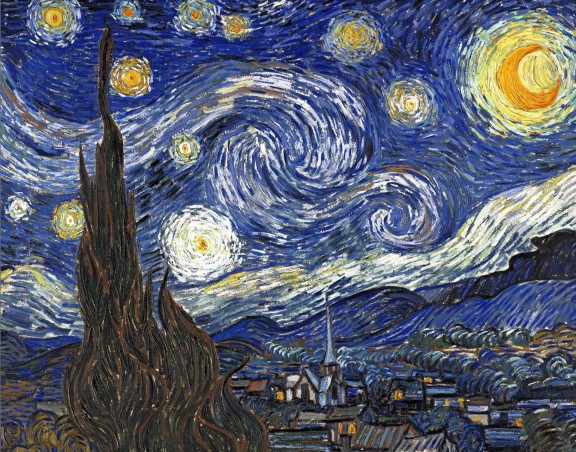

Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin imbued painting with emotional and spiritual resonance. Van Gogh’s bold, impasto brushwork and exaggerated colors conveyed his inner turmoil and passionate vision of the world (as in The Starry Night, 1889, where swirling skies and blazing stars reflect the artist’s agitated psyche). Gauguin, in works like Vision After the Sermon (1888), used flat areas of unnatural color and bold outlines – inspired by folk art and Japanese prints – to symbolize inner ideas and reject naturalism.

The Starry Night, 1889 – Painting by Vincent Van Gogh

Vision After the Sermon (1888) – Painting by Paul Gauguin

Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) exemplifies Post-Impressionism’s turn toward subjective expression. Van Gogh transformed the night sky over a Provençal village into a swirling dreamscape of color and movement, expressing emotion through bold brushstrokes and vivid contrasts rather than attempting a literal transcription of nature

What unites these artists is that they “worked independently” after Impressionism, each forging a personal style to go beyond capturing fleeting light.

They often infused their art with personal symbolism, whether through color, form, or motif. For instance, Van Gogh’s use of fiery yellows and cobalt blues and Gauguin’s exotic Tahiti scenes were vehicles for their individual search for meaning and authenticity in art.

Key Artists: Besides those mentioned: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who, while often classed with Impressionists, developed a striking graphic style in his posters and paintings of Paris nightlife; Émile Bernard, who along with Gauguin practiced Cloisonnism (flat regions of color bordered by dark contour lines); and Odilon Redon, who moved toward Symbolism, creating fantastical works that delved into dreams and the subconscious.

At the Moulin Rouge – Artwork by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Continuing Influence: The Post-Impressionists were hugely influential to the next generation. Cézanne was hailed as “the father of us all” by artists like Picasso and Matisse for showing new ways to represent reality. Van Gogh and Gauguin’s expressive use of color and distortion of form directly informed Fauvism and Expressionism in the early 20th century. The push towards abstraction and the idea that art can represent inner experience rather than external appearance has its roots here. In the curation context, exhibitions often trace lines from Post-Impressionist innovations to modern art – for example, from Seurat’s dot theory to digital pixelation, or from Gauguin’s primitivism to modern artists’ interest in non-Western art forms. Collectors, too, see Post-Impressionist works as bridges between the old world and modernism – they carry the beauty of Impressionist color with an added depth of meaning and innovation that continues to resonate.

Modernism and the Avant-Garde (1900–1940): Breaking All the Rules

As the 20th century dawned, artists in Europe (and eventually worldwide) dramatically expanded the vocabulary of art. Modernism in art refers to a host of avant-garde movements that sought to overturn traditional representation and explore new ways of seeing. The pace of change was rapid: each decade from 1900 to 1940 introduced revolutionary styles – Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, and more – each pushing boundaries further. Collectively, these movements questioned what art could be, reflecting a time of immense social and technological upheaval.

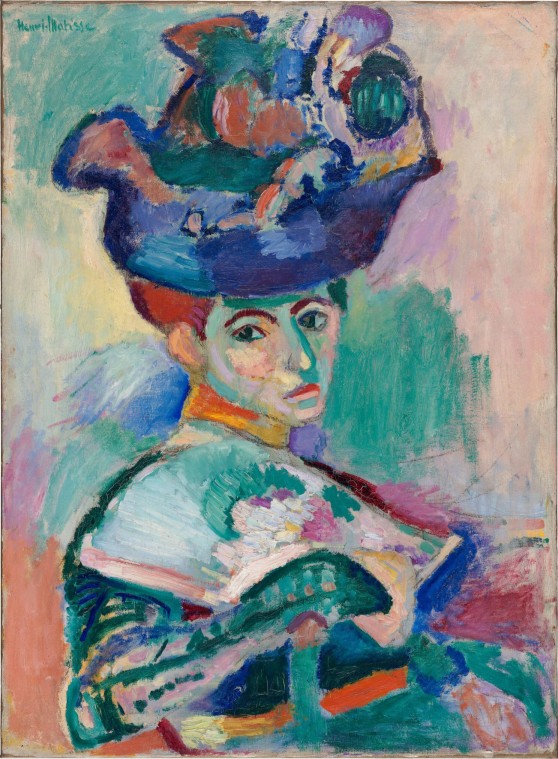

Fauvism (1905–1908): Led by Henri Matisse and André Derain in France, the Fauves (“wild beasts”) shocked audiences with explosive color and simplified forms. They liberated color from its descriptive role – using intense, non-naturalistic hues simply because they felt right emotionally or formally. For example, Matisse’s Woman with a Hat (1905) uses patches of vivid green and pink on the subject’s face. Fauvism had a short lifespan but was crucial in affirming color’s expressive autonomy. It was also a precursor to…

Matisse’s Woman with a Hat (1905) – Painting by Henri Matisse

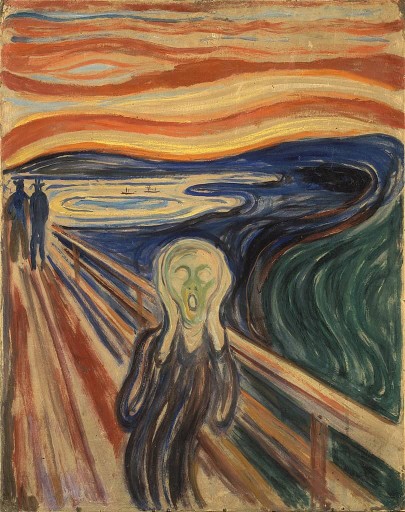

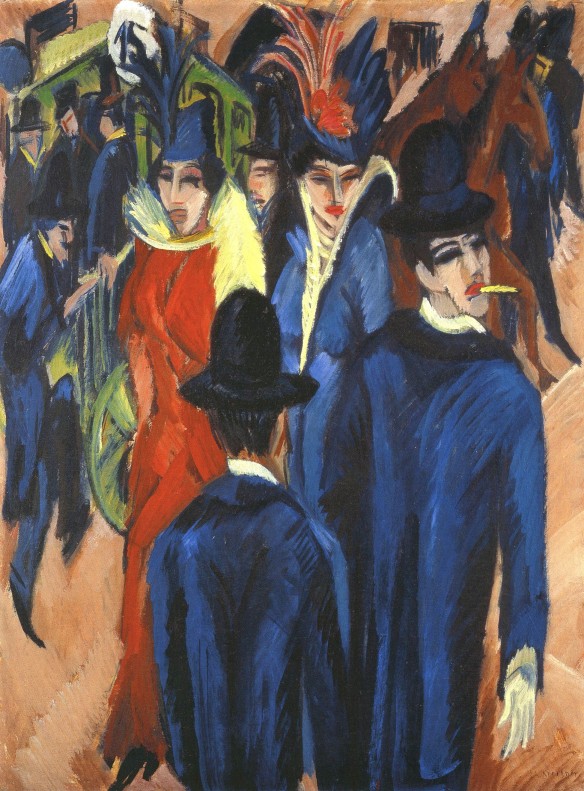

Expressionism (c. 1905–1920): In Germany and beyond, artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (of Die Brücke group) and Wassily Kandinsky (of Der Blaue Reiter) used distortion, jagged lines, and strong colors to convey angst, spirituality, or societal critique. Expressionist works often feature figural distortion and skewed perspectives to externalize inner emotions – see Kirchner’s street scenes with their eerie, elongated figures, or Edvard Munch’s iconic The Scream (1893, a forerunner of Expressionism) with its undulating forms embodying anguish. These artists were influenced by so-called “primitive” art (African, Oceanic, folk art) as a more authentic mode of expression. Expressionism set the stage for later abstract art that prioritized emotional impact.

The Scream (1893) – Painting by Edvard Munch

Kirchner Berlin Street Scene (1913) – Painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

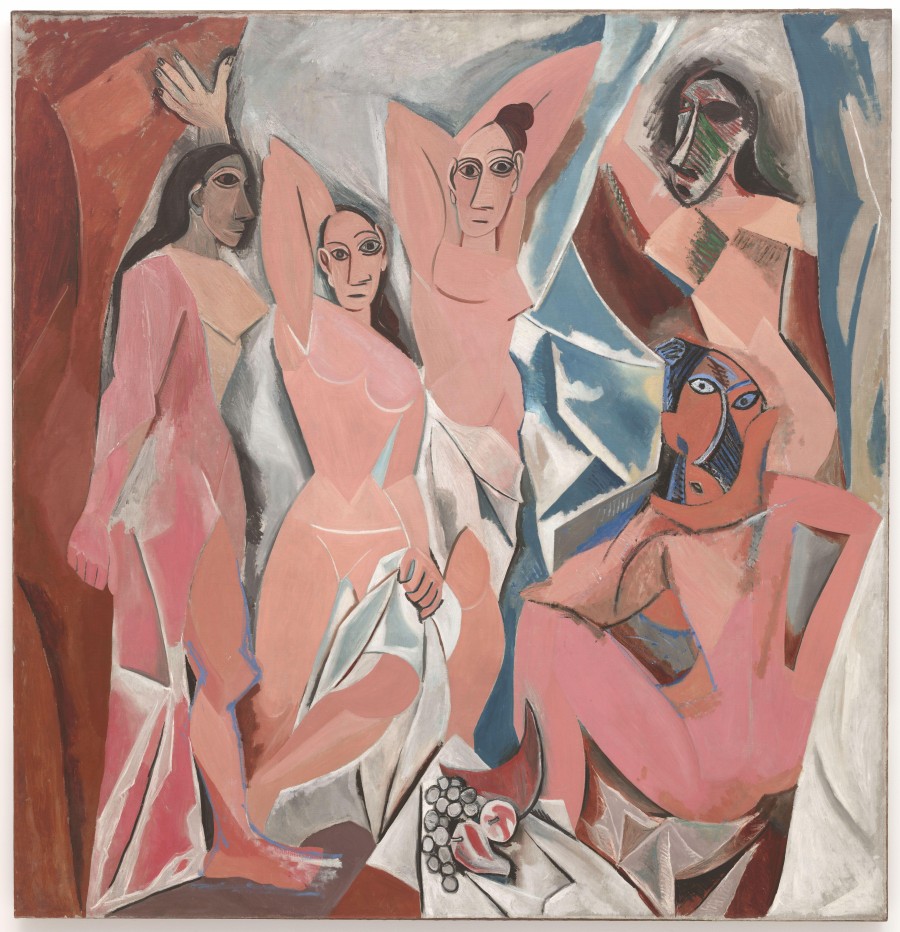

Cubism (1907–1914): Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism fractured the very form of reality on the canvas. Early (Analytic) Cubism dissected objects into geometric facets, representing multiple viewpoints simultaneously – the classic example is Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) with its angular figures and mask-like faces, a painting that shattered Renaissance perspective. Later (Synthetic) Cubism introduced collage elements and brighter color, reassembling reality in new ways (e.g., Picasso glueing oilcloth and newspaper onto canvas). Cubism’s core idea – that art can show an object from all sides at once or merge figure and background into interlocking shapes – was revolutionary. It directly influenced modern architecture, design, and further abstract art.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) – Painting by Pablo Picasso

Futurism (c. 1909–1916): Originating in Italy, Futurists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla exalted the dynamism of modern life – speed, machines, urban energy. Their art tried to depict motion itself (Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912, shows a dog’s feet multiplied in a blur). They often used Cubist-style fracturing combined with a brash, militant optimism for technology. While Futurism’s time was cut short by World War I and its leaders’ nationalism, it left a legacy in how artists depict movement and in embracing modern subject matter (cars, locomotives, electricity).

Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912 – Painting by Giacomo Balla

Dada (1916–1924): Arising during WWI in neutral Zurich and later in New York, Dada was less a style than an anti-art movement. Dadaists like Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, and Tristan Tzara were disillusioned by war and the rational society that produced it, so they championed absurdity, chance, and irreverence. Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), an ordinary urinal signed “R. Mutt”, essentially invented the readymade and questioned art’s very definition. Dada collages and photomontages, such as Höch’s slicing together of newspapers and photos, mocked politics and societal norms. Though Dada was short-lived, it opened art to concept over craft – a radical idea that led directly to surrealism and much of contemporary conceptual art.

Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) – Marcel Duchamp

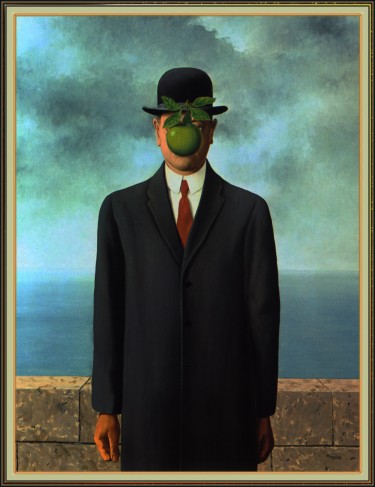

Surrealism (1920s–1940s): Emerged from Dada’s ashes in Paris under André Breton’s leadership, Surrealism sought to tap the unconscious mind and dreams as the source of artistic truth. Influenced by Freud’s psychoanalysis, Surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Max Ernst created works that defy reason – bizarre, dreamlike juxtapositions that challenge our perception. Dalí’s melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory (1931) or Magritte’s The Son of Man (a man with an apple obscuring his face) use realistic techniques to paint impossible scenes, thereby jolting the viewer into questioning reality. Some Surrealists used automatism – drawing or writing freely without conscious control – to unlock creativity. Surrealism’s emphasis on imagination and the subconscious has had profound influence on literature, film, and visual art to this day.

The Persistence of Memory (1931) – Painting by Salvador Dali

The Son of Man – Painting by René Magritte

Clearly, the early 20th century was a torrent of innovation. Artists rebelled against previous conventions, each movement building upon or reacting to others in quick succession. By the 1930s and 40s, further developments like Abstract Expressionism were on the horizon, fueled by these avant-garde breakthroughs.

Influence: The Modernist movements shattered the notion that art must imitate visible reality. They expanded the possibilities: art could be purely abstract (Kandinsky made one of the first purely non-objective paintings around 1911), art could incorporate found objects (Duchamp), art could be about ideas or emotions more than images. For curators, Modernism offers rich material to create dialogues – for instance, how a Cubist collage presaged digital sampling, or how Surrealist games echo in contemporary interactive art. Collectors of modern art prize these works for their historical importance and often bold aesthetics; understanding each movement’s manifesto and context (many had manifestos and were tied to social/intellectual trends) is key to appreciating their meaning

From a broader perspective, the first half of the 20th century in art was about breaking free – from academic rules, from linear perspective, from the entire notion of what subjects were “appropriate” in art. The diversity of Modernism set the stage for the even more eclectic approaches of contemporary art, where anything goes can be traced back to these seminal experiments.

Abstract Expressionism (1940s–1950s): The New York School and Action Painting

In the aftermath of World War II, the art world’s center of gravity shifted from Paris to New York. There, a group of American painters launched Abstract Expressionism, the first major American art movement, marked by large-scale abstractions that emphasized the act of painting itself as a means of expression

Sometimes called the New York School, these artists were influenced by Surrealist ideas of the unconscious, but instead of precise dream imagery, they used spontaneous, gestural techniques to create epic, non-representational works.

Characteristics: Abstract Expressionist paintings are typically very large and completely abstract, with no recognizable subject matter. They often showcase gesture and process – viewers can almost “see” the artist’s movements in the drips, splatters, strokes, or fields of color. Two broad approaches emerged:

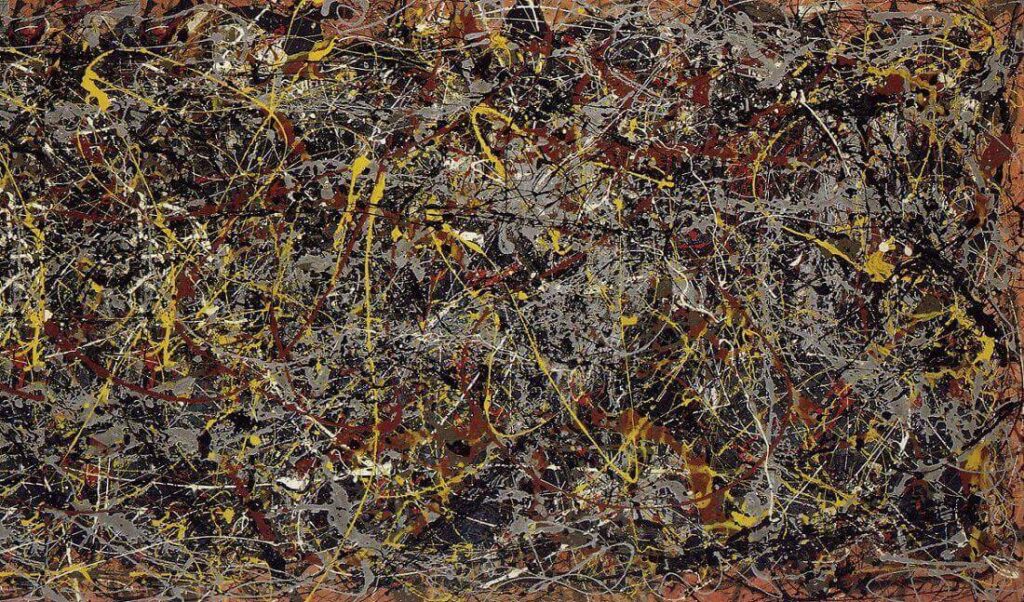

Action Painting: epitomized by Jackson Pollock, who famously laid canvases on the floor and dripped or flung paint in rhythmic motions. Pollock’s drip paintings like No. 5, 1948 are dense tangles of line and paint; they have no central focal point, enveloping the viewer in their all-over web. This method highlighted the performance of painting – the canvas as an arena in which the artist acts (critic Harold Rosenberg’s famous description)

No. 5, 1948 – Painting by Jackson Pollock

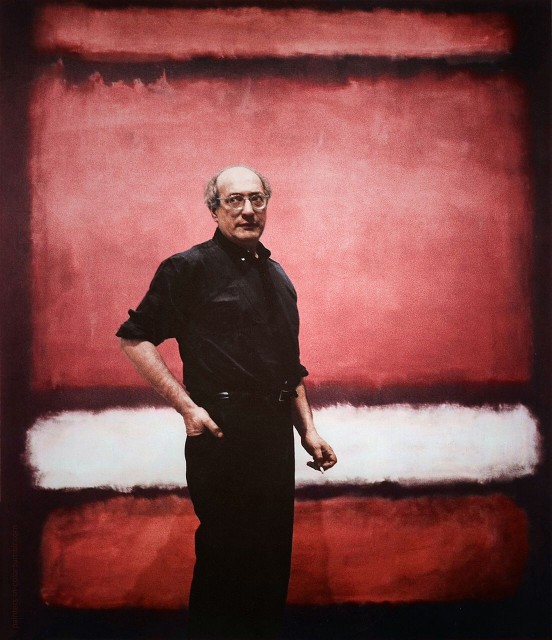

Color Field Painting: exemplified by artists like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, who applied large areas of flat color to evoke mood or spirituality. Rothko’s signature works feature soft-edged rectangular clouds of color stacked against colored grounds, inviting quiet contemplation. Though static compared to Pollock, Rothko’s paintings are emotionally charged; he aimed to express basic human emotions (tragedy, ecstasy, doom) through color alone

Mark Rothko

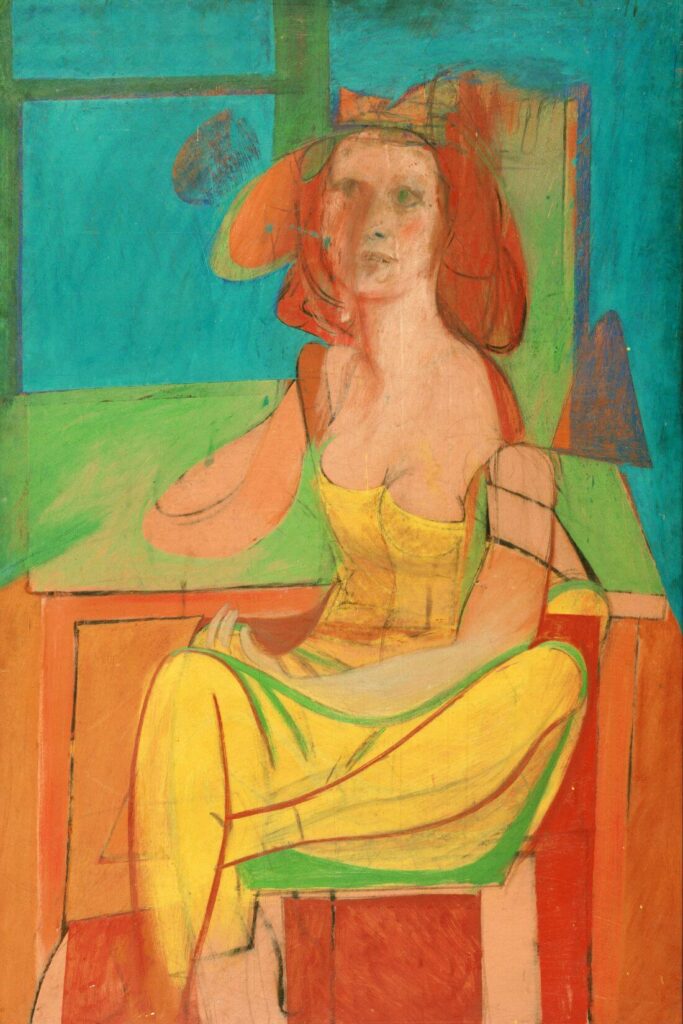

Other notable Abstract Expressionists include Willem de Kooning, whose ferocious brushwork produced abstracted figures (his Woman series blurred the line between figuration and abstraction with slashes of paint); Franz Kline, known for monumental black and white brushstroke compositions; and Helen Frankenthaler, who in the 1950s pioneered a soak-stain technique (pouring thinned paint onto unprimed canvas) that influenced the next generation.

Seated Woman – Painting by Willem de Kooning

Impact: Abstract Expressionism announced that American art had come of age. It broke decisively from European traditions, emphasizing freedom, individualism, and the subconscious. These artists also benefited from Cold War politics – American institutions promoted Abstract Expressionism globally as a symbol of Western creative freedom (in contrast to Soviet socialist realism).

Curatorially, Abstract Expressionist works are often showcased for their scale and emotional impact; many modern art museums dedicate entire rooms to single canvases to allow immersive viewing. For art collectors, owning a piece by a Pollock or Rothko is like holding a piece of postwar cultural history – these works remain some of the most sought-after. In terms of influence, Ab Ex opened the door for all manner of subsequent abstraction and experimental art in the 20th century, from Minimalism to performance art. It also foregrounded the artist’s gesture and choice as content in itself, a concept that would lead to movements like Conceptual art (where the idea is primary) and would inform how later artists approach process-oriented work

Pop Art (1950s–1960s): Art in the Age of Mass Media

By the late 1950s, a new wave of artists began turning their attention to the imagery of consumer culture, advertising, and pop entertainment. Pop Art emerged first in Britain and then took off in the United States, effectively blurring the boundaries between “high art” and “popular culture.” It was a reaction against the perceived elitism of Abstract Expressionism – Pop artists reintroduced imagery, but from the everyday world of mass-produced goods and celebrity icons.

Characteristics: Pop Art is marked by bold, flat colors and clear lines, often borrowing the look of commercial graphics. Common subjects include brand logos, comic strips, advertisements, celebrities, and ordinary consumer items.

The approach is frequently ironic or coolly detached – presenting a Campbell’s soup can or a comic book frame with the same deadpan emphasis as a traditional still-life, thereby challenging what is worthy of artistic depiction.

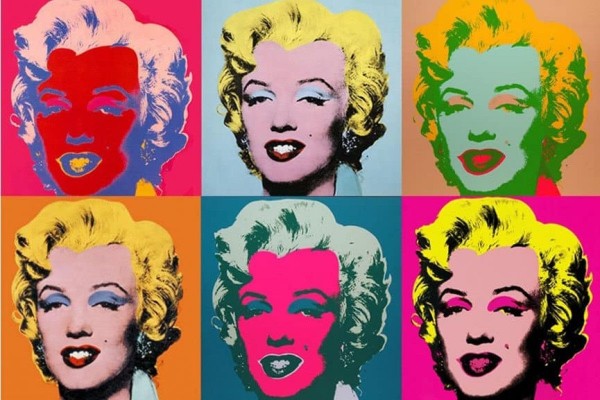

In the US, Andy Warhol is the quintessential Pop artist. His series of Campbell’s Soup Cans (32 nearly identical canvases of different soup flavors) and silkscreened portraits of Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley reproduced mechanically the images everyone recognized, underscoring how mass media shapes our collective consciousness.

Shot Marilyns – Painting by Andy Warhol

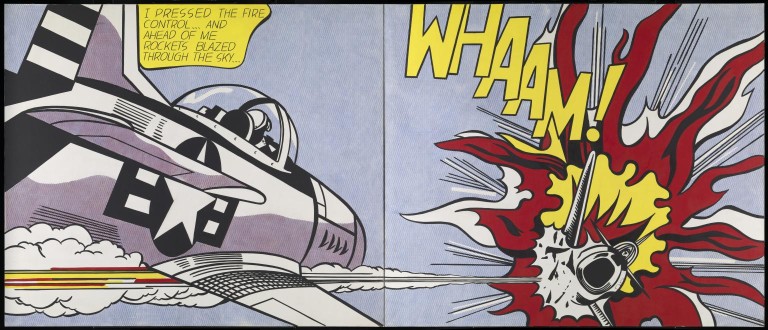

Warhol’s studio, “The Factory,” even operated like a manufacturing unit for art, further eroding the aura of unique craftsmanship. Roy Lichtenstein, another pillar of Pop Art, blew up comic book panels onto large canvases, complete with Ben-Day dots and speech bubbles – works like Whaam! (1963) mimic the printing process and celebrate the melodrama of comics, while subtly satirizing it.

Whaam! (1963) – Artwork by Roy Lichtenstein

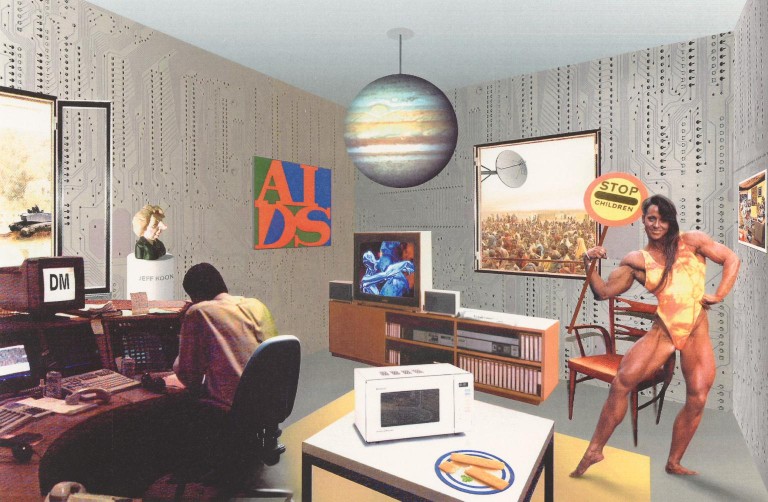

British Pop artists like Richard Hamilton (creator of the 1956 collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?) and David Hockney (in some phases of his career) were also influential, incorporating imagery of modern living and sometimes a sly commentary on society’s obsessions.

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different?’, Richard Hamilton, 1992

Philosophy: Pop Art declared that anything could be art, not by elevating the subject (like Duchamp did with Dada) but by presenting it as-is and inviting the viewer to consider it anew. In doing so, Pop artists implied that the distinction between art and commerce is arbitrary. As Warhol famously quipped, “Making money is art… and good business is the best art.” This movement thus reflected the booming post-war economy and the saturation of images from television, magazines, and billboards.

Legacy: Pop Art’s impact is immense in contemporary visual culture. It presaged the postmodern idea that images can be recontextualized endlessly. We see its influence in today’s appropriation art, in graphic design, and in the self-aware blending of commercial and fine art realms (think of Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs or the ubiquitous use of celebrity imagery in art). Curators often mount Pop Art exhibitions to explore themes of consumerism and media; such shows tend to attract a wide audience, as the imagery is inherently accessible and nostalgic. Collectors find Pop Art appealing both for its cultural resonance and its often decorative, striking quality – a Warhol screenprint or a Lichtenstein print can be a status symbol and a conversation piece about mass culture.

In the grand timeline, Pop Art served as a bridge from modern to postmodern – after Pop, the door was open for artists to freely mix imagery from any source, parody cultural icons, and engage directly with the capitalist world. It made art fun and provocative in a new way, ensuring that the conversation about what art is and can be would never be the same.

Late 20th Century and Contemporary Art (1970–Present): Pluralism and Innovation

From the 1970s onward, art movements proliferated in many directions, reflecting a world of rapid change, diverse voices, and new technologies. Rather than one dominant style, contemporary art is characterized by pluralism – a coexistence of myriad approaches and ideas. Still, several noteworthy trends and “movements” can be highlighted to make sense of the post-1970 art landscape:

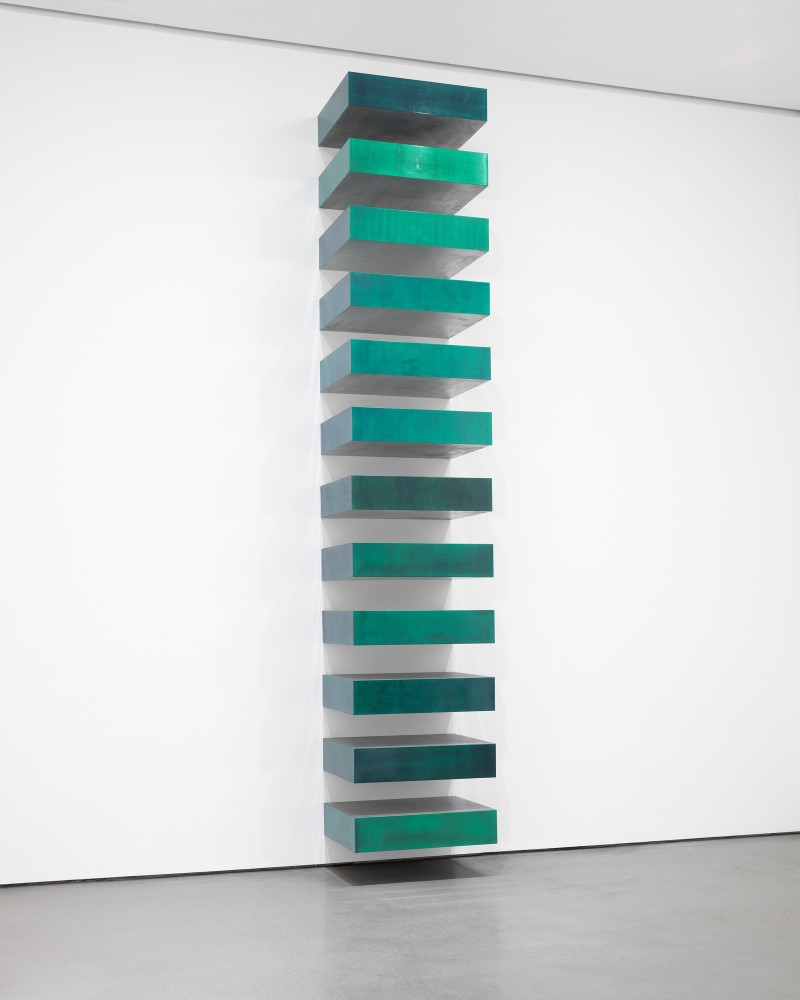

Minimalism (1960s–1970s): Reacting against the emotional excess of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalist artists like Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, and Frank Stella created art stripped to fundamentals. Simple geometric forms, repetition, and industrial materials define Minimalism. A famous example is Judd’s stacks of metal boxes protruding from a wall at regular intervals. Minimalism asked the viewer to focus on the object itself and the space it occupies, rather than any representation or metaphor. This movement heavily influenced architecture, design, and later conceptual art.

Untitled. 1967 – Donald Judd

Conceptual Art (late 1960s–1970s): Here, the idea behind the work takes precedence over traditional aesthetics or materials. Pioneers like Joseph Kosuth (who displayed a chair, a photo of the chair, and a dictionary definition of “chair” to examine how we understand an object. and the collective Art & Language essentially turned art into philosophy. Documentation, text, maps, or performance could all be the artwork. Conceptual art paved the way for much of contemporary practice, where we routinely accept that, say, a list of instructions or a performance piece can be considered art.

Joseph Kosuth

Performance and Body Art (1960s–1980s): Artists such as Marina Abramović, Yoko Ono, and Chris Burden used their own bodies and live actions as media. These ephemeral works – from Abramović’s endurance-testing pieces to Ono’s audience-participation Cut Piece (1964) – emphasize experience and often confront social or political issues. The documentation (videos, photographs) often becomes the only lasting trace.

Marina Abramović

Installation Art (1970s–present): Instead of discrete paintings or sculptures, artists create immersive environments. Installation art can fill a room or an outdoor space, engaging multiple senses. For example, Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms enclose viewers in mirror-lined chambers with repeating light patterns, creating a transcendent experience. Land Art (or Earth Art) like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) extends this idea into the landscape itself.

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms

Postmodernism (1970s–1990s): More a cultural condition than a style, postmodern art is often characterized by irony, appropriation, and a mix of high and low culture. The Pictures Generation (artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince) used photography and media imagery to question identity and representation, often rephotographing or editing existing images to critique how images shape reality. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring brought graffiti aesthetics into galleries, blending street culture with fine art. Postmodernism in art is skeptical of grand narratives and often references art history itself in a tongue-in-cheek way.

Untitled #648 – Cindy Sherman

Feminist Art (1970s–present): Spurred by the feminist movement, artists like Judy Chicago (who created The Dinner Party, 1979, an installation celebrating women in history) and Guerrilla Girls (an anonymous collective that calls out sexism in the art world) directly addressed gender politics. They expanded art to include traditionally “feminine” crafts (textiles, ceramics) and personal narratives, effectively broadening what subject matter was considered legitimate.

The Dinner Party – Judy Chicago

Street Art (1980s–present): With figures like Banksy in the 2000s bringing it to global attention, street art and graffiti have become recognized art movements. What began as illicit tagging and murals in urban environments evolved into a major contemporary genre, often merging graphic design, pop culture, and political activism. Artists such as Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and Kehinde Wiley (who, while not a street artist, paints street-culture-inspired portraits) have infused contemporary art with references to hip hop, skate, and protest culture.

Balloon Girl (London) – Banksy

Digital and New Media Art (1990s–present): With the rise of computers, the internet, and now AI, many artists engage with new media – from digital painting and video art to interactive art and virtual reality. Pioneers like Nam June Paik (video art) and Bill Viola (video installations) set the stage. Today, digital art is everywhere, including the realm of NFTs (non-fungible tokens), where blockchain technology allows ownership of digital artworks. Digital art often explores the boundary of human and machine creativity, reflecting on how technology changes our experience of art and life.

Nam June Paik (video art)

Given this explosion of approaches, contemporary art defies easy summary. It is global and inclusive: artists from all backgrounds contribute, bringing in perspectives from non-Western traditions and addressing issues like identity, globalization, and climate change. “Contemporary Art” essentially means art of our time, and it is constantly evolving.

For collectors and curators, the contemporary period is exciting but challenging – there’s such diversity that understanding context is crucial. Exhibitions often focus on themes (e.g., identity, technology, or environmental art) rather than movements, given the overlap and individuality of today’s art. Art history in the making is visible through biennales, art fairs, and a worldwide art market.

One consistent thread is that contemporary art remains in dialogue with the past. Many works explicitly reference earlier movements – a video installation might echo a Renaissance painting, or a performance might recreate a piece from the 1970s – proving that the arc of art history is a conversation across time.

Appreciating Art History: Insights for Collectors and Curators

Understanding art history isn’t just an academic exercise – it offers practical benefits for anyone involved in collecting or curating art. Each artwork, whether a centuries-old painting or a cutting-edge digital piece, is part of a larger story. Here are some insights on how knowledge of art history can enhance appreciation and decision-making in the art world:

Contextual Appreciation: Knowing the hallmarks of each movement allows collectors and curators to place a work in context. For instance, recognizing a Baroque painting’s dramatic lighting or a Cubist print’s fragmented form can inform its attribution, value, and significance. It also deepens enjoyment – one can appreciate a modern portrait’s elongated forms as a nod to El Greco’s Mannerism or see a contemporary installation and recall its Surrealist or Dadaist ancestors.

Building a Cohesive Collection: For collectors, studying art history is “paramount to building a thoughtful, cohesive collection”, A collection with works from various eras can be unified by understanding influences and dialogues between them. A collector might, for example, display a classical sculpture replica alongside a Neoclassical painting and a modern Minimalist piece, creating a narrative about form and timeless aesthetic ideals. Knowledge prevents random purchases and inspires more meaningful acquisitions that complement each other.

Curation and Storytelling: Curators craft exhibitions that often bridge past and present – say, pairing Old Master drawings with contemporary works to highlight enduring themes like portraiture or political protest. With a solid grasp of art history, curators can draw illuminating comparisons and create shows that educate and engage the public. They can, for example, show how Impressionism influenced contemporary plein-air painters, or how African masks (which influenced Picasso) can be displayed next to Cubist art, fostering cross-cultural understanding.

Recognizing Quality and Authenticity: Historical knowledge equips one to discern the innovations or mastery in a piece. Collectors can better judge a work’s quality by comparing it to known benchmarks from art history. They can ask: Is this abstract painting derivative of earlier styles, or does it add something new? Curators similarly can identify which artists are true visionaries versus those rehashing old ideas. Additionally, understanding materials and techniques from history aids in spotting forgeries or misattributions.

Value Insight: The art market often operates in cycles of rediscovery. An overlooked movement (say, the Baroque, or mid-century women Abstract Expressionists) might suddenly gain attention. Collectors aware of art-historical importance can anticipate or recognize when a body of work deserves greater recognition (and value) due to its place in history. Curators, too, can rejuvenate an artist’s reputation by contextualizing them appropriately – for instance, staging the first major retrospective of a regional movement, explaining its historical role.

Influence on Contemporary Art and Curation: Many contemporary artists consciously reference art history in their work – a photographer might imitate Renaissance compositions, or a digital artist might “glitch” a famous painting. As noted earlier, artists like Banksy infuse art-historical references (Banksy has parodied Monet’s lily pond with shopping carts in the water, for example). Curators fluent in these references can interpret and present such works with richer commentary. Furthermore, modern museum practices, from exhibition design to conservation, often draw lessons from history (how artworks were originally displayed or meant to be seen).

Education and Audience Engagement: For those guiding others through art – docents, gallery owners, curators – the stories of art history provide a toolkit to engage audiences. Explaining a piece’s background or its artist’s influences can turn a casual viewer into an enthusiast. For instance, telling the story of how Impressionists were rebels in their time. can make a familiar Monet painting take on new excitement for a viewer.

In short, art history acts as a foundation and a framework. It allows collectors and curators to make informed choices, create meaningful collections or exhibitions, and preserve the continuum of artistic achievement. As the art historian E.H. Gombrich noted, “One cannot learn to see a picture without having seen many before.” Each movement we’ve covered adds to that wealth of experience, sharpening the eye for what comes next.

Finally, an often overlooked practical tip in today’s digital age: when presenting or archiving art, whether online or in catalogs, optimize images with proper titles and alt-text, and use relevant keywords. For example, a collector documenting their pieces should label a photo “Claude Monet Impression Sunrise 1872 painting” rather than a generic file name – this not only helps in organizing their digital collection but also improves visibility if shared online (an SEO consideration). Curators putting content on museum websites likewise benefit from descriptive captions that include artist, title, and movement (e.g., “Baroque portrait by Caravaggio”) so that search engines – and more importantly, people – can find and appreciate these connections easily. Such practices ensure that the rich tapestry of art history is accessible to all, bridging the past and present in the virtual space as well.

Conclusion: The Ever-Evolving Tapestry of Art History

From the mysterious cave paintings of prehistoric times to the conceptual installations of today, art history unfolds as an ever-evolving narrative of human expression. We have journeyed through major movements – witnessing the rebirth of classical ideals in the Renaissance, the flamboyance of Baroque, the radical light of Impressionism, the fractured visions of Modernism, and the boundless experimentation of the contemporary era. Each movement, with its distinctive voice and vision, has built upon those before it, contributing threads to a vast tapestry that is our shared cultural heritage.

Understanding these movements enriches our experience of art. We come to see that a simple line drawing can carry the weight of millennia of refinement, or that an abstract sculpture can be a dialogue with nature as old as humanity. We recognize the significance of context: art does not emerge in a vacuum but is shaped by its time – the beliefs, technologies, and challenges that artists grapple with. And yet, as we trace influences, we also appreciate each era’s unique innovations. The past continually inspires the present: contemporary artists often pay homage (directly or indirectly) to historical styles, and modern curators craft exhibits that juxtapose eras to spark new insights.

For the art enthusiast, collector, or curator, a solid grounding in art history offers not only deeper appreciation but also a sense of connection – with artists long gone and with the creative currents that flow through time. It encourages us to keep exploring: perhaps today you admire Van Gogh’s vibrant post-impressionist skies; tomorrow you might delve into the world of Japanese ukiyo-e that inspired him, or the Expressionists he, in turn, influenced. The study of art history is a journey with endless side paths and discoveries.

In a practical sense, this overview has highlighted how to identify and appreciate key movements, how they influenced one another, and how they continue to inform artistic practice and curation. But it is only a starting point. We encourage you to further explore the artworks and artists mentioned – visit museums (in person or virtually), browse art books, or take a closer look at that painting on your wall with fresh eyes. Each piece of art has a story woven into the grand story of art history.

Ultimately, art history teaches us that art is a living conversation across the ages. By engaging with it, we become part of that conversation. Whether you are deciding on a new artwork for your collection, organizing an exhibition, or simply enjoying a painting for its beauty, the perspectives of art history will enhance your experience and understanding. As you continue to explore, remember that every “movement” was once an avant-garde idea in someone’s mind – and the spirit of creativity that drove those movements is very much alive today.

Art history, like art itself, is never truly “complete” – it’s a comprehensive overview that keeps expanding. So let this be an invitation to keep learning and looking. The more you discover about the past, the more you’ll see in the art around you now, and the greater your appreciation for the profound significance of this human endeavor we call art. Enjoy the journey through time, and perhaps someday, you’ll find yourself adding your own chapter to the story of art history.

For further reading and visual reference, consider resources like Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, the Metropolitan Museum’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, and the rich collections of museums (many accessible online). These can provide deeper dives into each movement discussed, from the cave art of Lascaux to the latest in digital installations.