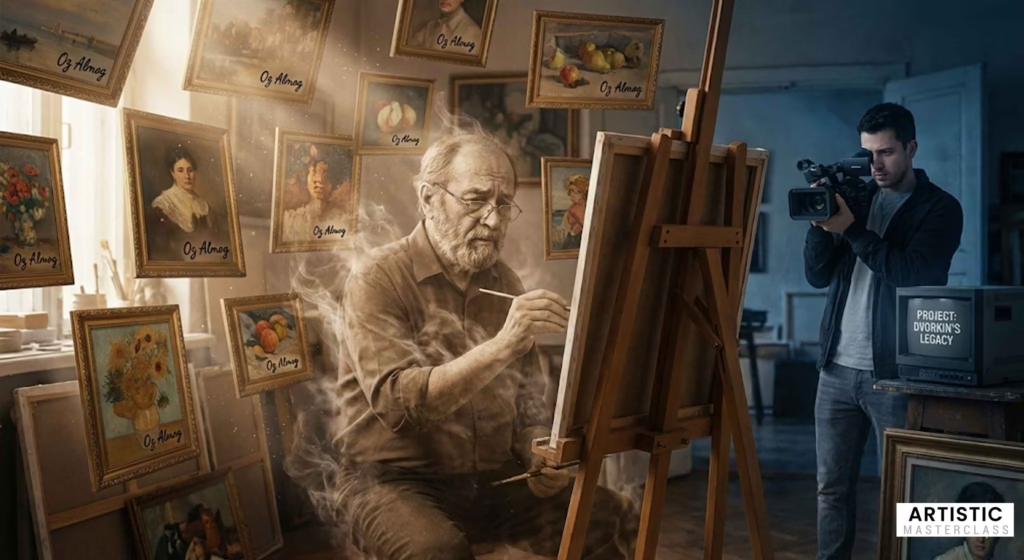

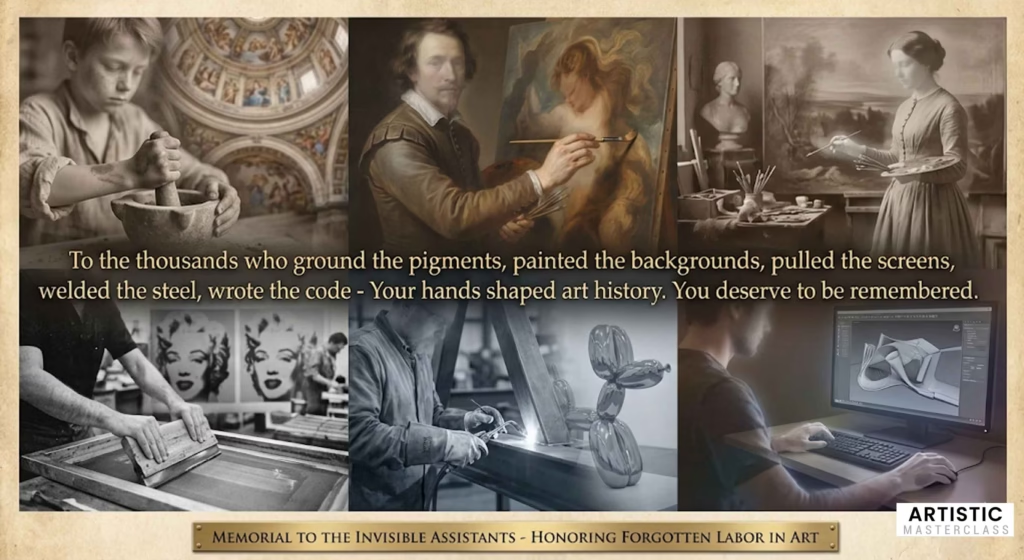

When Vladimir Dvorkin died in 2014, thousands of his paintings hung in museums and private collections around the world. But none bore his name. For decades, this skilled artist had created works for Israeli painter Oz Almog, who signed them and sold them as his own. Dvorkin’s grandson would later discover the truth through a documentary investigation, but by then, his grandfather had passed away—his talent recognized only by those who paid to see “Almog’s” work in galleries.

Dvorkin’s story is not unique. It echoes across six centuries of art history, from Renaissance workshops where teenage apprentices ground pigments for Michelangelo, to contemporary studios where teams of fabricators execute Jeff Koons’ balloon sculptures. When you admire masterpieces in museums—the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Warhol’s silkscreens, Damien Hirst’s spot paintings—you’re often seeing the work of many hands, most unnamed, uncredited, and historically erased.

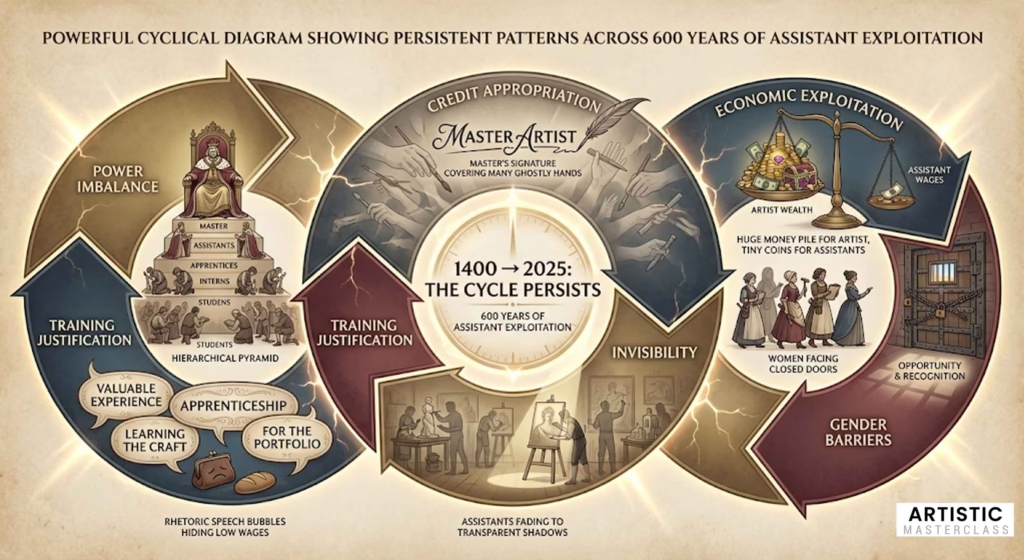

This is the hidden labor of artist’s assistants throughout history: the apprentices who mixed paints and filled in backgrounds while masters took sole credit, the women who faced double barriers of workshop exclusion and gender erasure, the contemporary fabricators paid hourly wages while works sell for millions. Their contributions shaped art history, yet their names remain unknown.

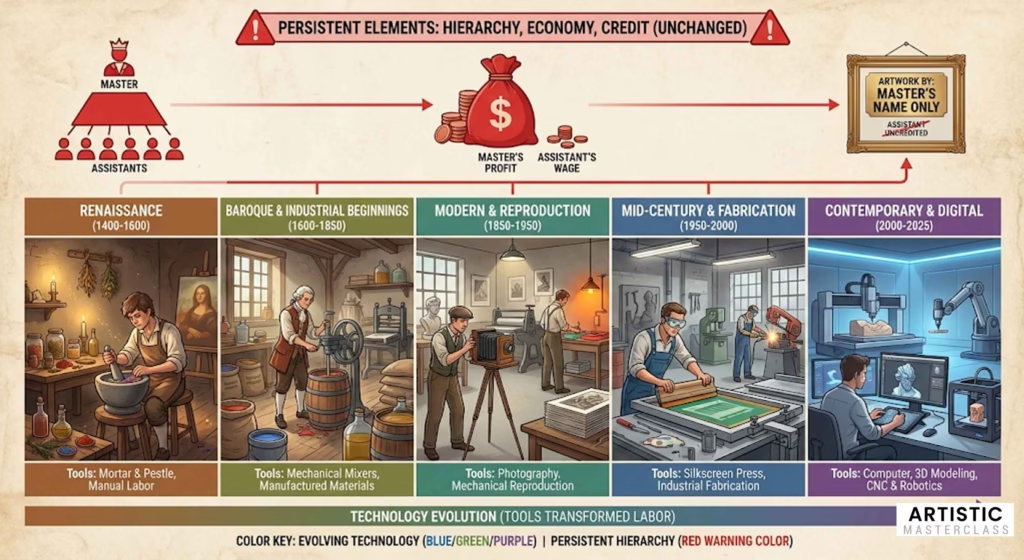

What follows is the complete story art history often obscures—a 600-year journey from Renaissance bottega to modern art fabrication, revealing persistent patterns of invisible labor, economic exploitation, and the fundamental question: who deserves credit when art is truly a collaborative process?

The Renaissance Bottega: Where the System Began

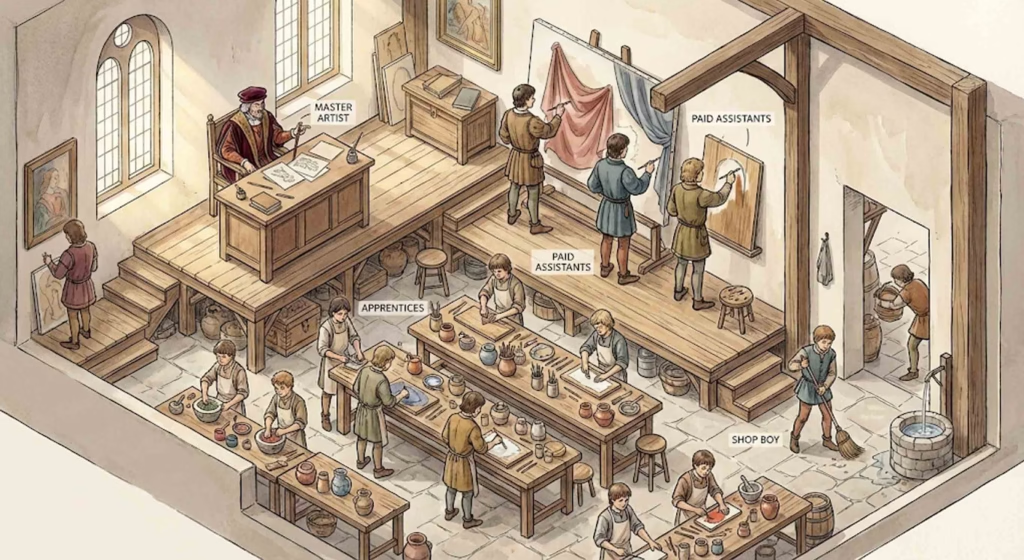

The Renaissance workshop—called a bottega in Italian—established patterns that persist six centuries later. These weren’t romantic studios where solitary geniuses contemplated beauty. They were crowded, noisy production facilities where masters managed teams of assistants, apprentices, and shop boys in a hierarchical system designed to maximize output while controlling credit and profit.

Inside a 15th Century Workshop: Daily Life and Power Structures

Picture a typical Florentine bottega in 1470. The space serves multiple functions: art production facility, training school, and often living quarters. Wooden tables crowd the room, covered with pigment jars, partially finished panels, and drawing portfolios. The smell of linseed oil and ground minerals fills the air. Natural light streams through large windows—essential for color accuracy—while in corners, shop boys tend fires for heating glues and preparing materials.

The social hierarchy is rigid and clearly defined. At the top sits the master artist, perhaps Andrea del Verrocchio or Lorenzo Ghiberti, who signs all work leaving the shop. Below him are paid assistants—former apprentices skilled enough to handle significant portions of commissions. These men might paint entire backgrounds, fill in drapery, or execute repetitive decorative elements while the master concentrated on faces and central figures.

Further down the ladder are apprentices, typically boys aged 12 to 14, contracted for terms lasting anywhere from one to eight years. They begin with menial tasks: grinding pigments from minerals using mortar and pestle, preparing wooden panels with multiple coats of gesso, cleaning brushes, running errands. The work is tedious and physically demanding. Grinding ultramarine blue from lapis lazuli could take hours of repetitive motion, producing the precious pigment worth more than gold.

At the bottom are shop boys (garzoni) who handle the most basic work—sweeping, fetching water, holding materials. Historical records also document an uncomfortable reality rarely discussed: some Renaissance workshops employed slaves to perform preparatory labor. These individuals had no path to advancement and received no compensation beyond survival.

The economic model depended on this pyramid. Wealthy patrons commissioned the master, who employed the team. The master’s signature commanded premium prices. Contracts often specified which parts “must be by the master’s hand”—usually faces and central figures—acknowledging that assistants would execute much of the work. Everyone understood this reality, yet the fiction of sole authorship persisted.

The Apprentice’s Journey: From Grinding Pigments to Painting Hands

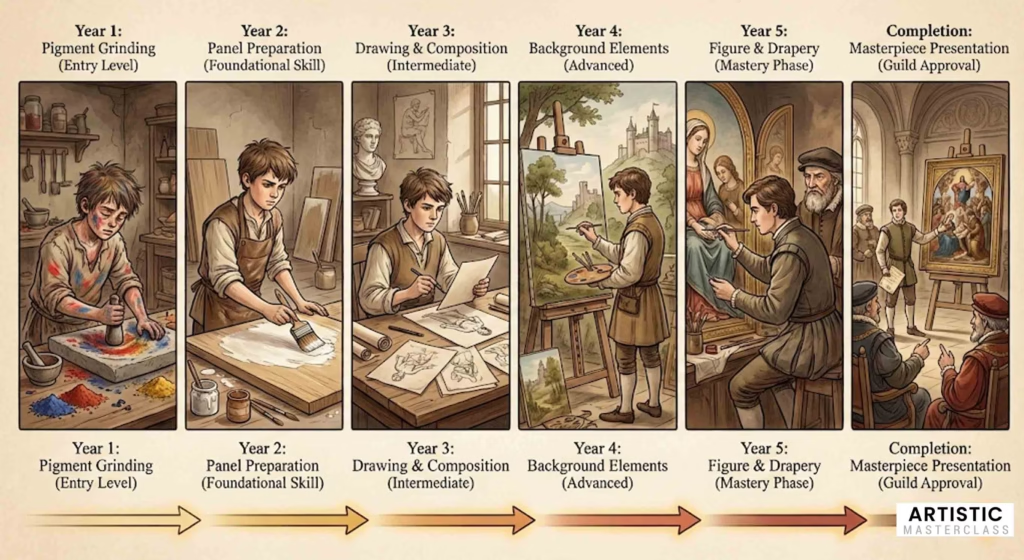

An apprentice’s education followed a predictable progression, though the timeline varied based on talent and the master’s assessment. Parents or guardians signed contracts with the master, sometimes paying fees for the privilege of training, other times receiving modest stipends for their son’s labor. The contract bound both parties: the master agreed to provide instruction, room, and board; the apprentice committed to obedience and service.

The first year was brutally monotonous. New apprentices ground pigments—red ochre from iron oxide, brilliant vermillion from mercury and sulfur, expensive ultramarine from imported lapis lazuli. They learned which minerals were toxic (many were) and which required specific preparation. They mixed binding media: egg tempera for panel paintings, fresco plaster for walls, oil glazes for the new Flemish techniques spreading through Italy.

They prepared panels, applying multiple thin coats of gesso (rabbit-skin glue mixed with chalk), sanding between layers until the surface was smooth as silk. They stretched and primed canvas. They maintained the workshop, learning that art production required constant material management.

Around year two or three, apprentices graduated to drawing. They copied their master’s sketches repeatedly, learning to reproduce his style so accurately that their drawings became indistinguishable from his originals. These drawing collections were among a workshop’s most valuable possessions—carefully guarded and passed down through generations. Leonardo da Vinci, training in Verrocchio’s workshop around 1466, would have spent hundreds of hours copying his master’s drawings before touching a paintbrush.

By year four or five, talented apprentices began assisting on actual commissions. They might paint backgrounds—distant landscapes, architectural elements, decorative borders. The master would sketch the composition, perhaps indicate colors, then assign sections to assistants based on their abilities. The best assistants earned the privilege of painting secondary figures, hands, or drapery folds while the master concentrated on faces.

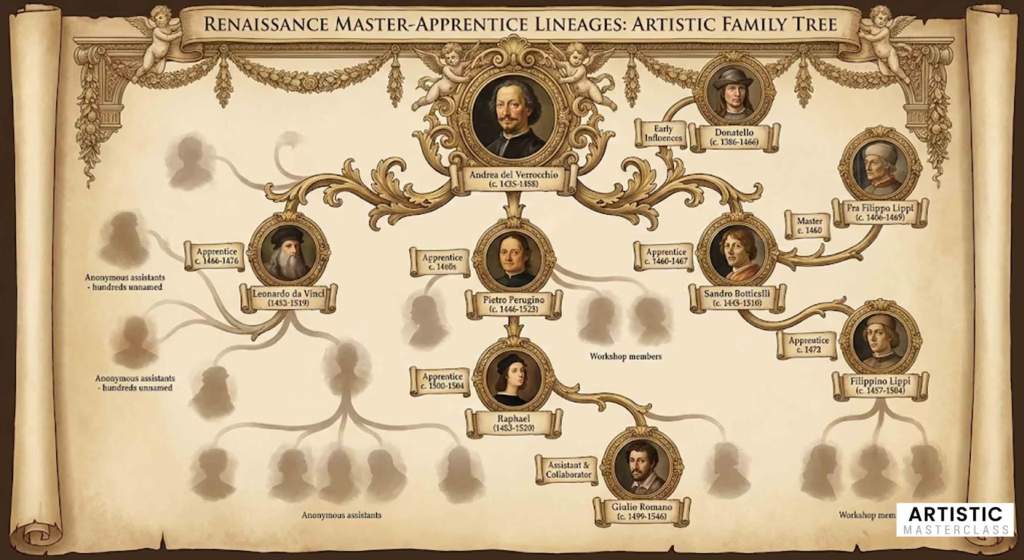

This training system produced remarkable artists. Leonardo learned from Verrocchio, who had learned from Donatello. Raphael trained under Perugino, who had studied with Verrocchio alongside Leonardo. Sandro Botticelli learned from Fra Filippo Lippi, then trained Filippino Lippi. The Renaissance was a small world where knowledge passed directly from master hands to apprentice hands.

But for every Leonardo who surpassed his master, hundreds of talented assistants remained anonymous. Upon completing their apprenticeship, they had to submit a “masterpiece” to their city’s guild for approval. Only after passing this test—and paying guild fees—could they establish their own workshops. Many couldn’t afford the fees. Others lacked family connections or wealthy patrons. They remained in workshops their entire careers, painting backgrounds and mixing colors while their masters became famous.

The Credit Problem Emerges: Who Really Painted the Masterpiece?

The attribution question haunted Renaissance art from the beginning and persists today. When a master signs a painting completed largely by assistants, who is the true artist?

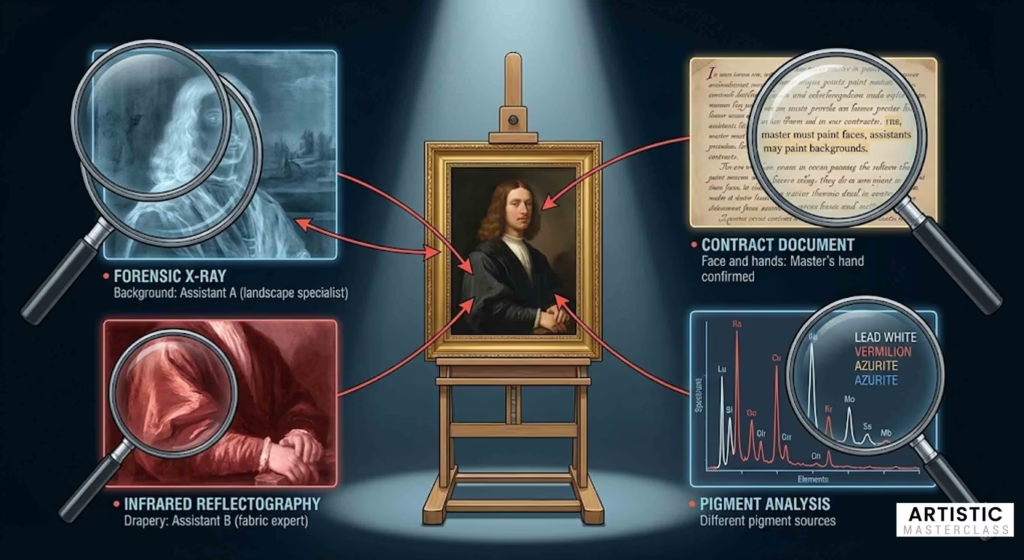

The economic stakes were enormous. A painting definitively by Rembrandt’s hand might sell for five times the price of one from his workshop. Collectors understood the difference and contracts reflected it. A 1483 agreement for the Virgin of the Rocks specified that Leonardo himself must paint certain elements. These contractual specifications acknowledged reality: workshop collaboration was standard, but the master’s personal touch commanded premium prices.

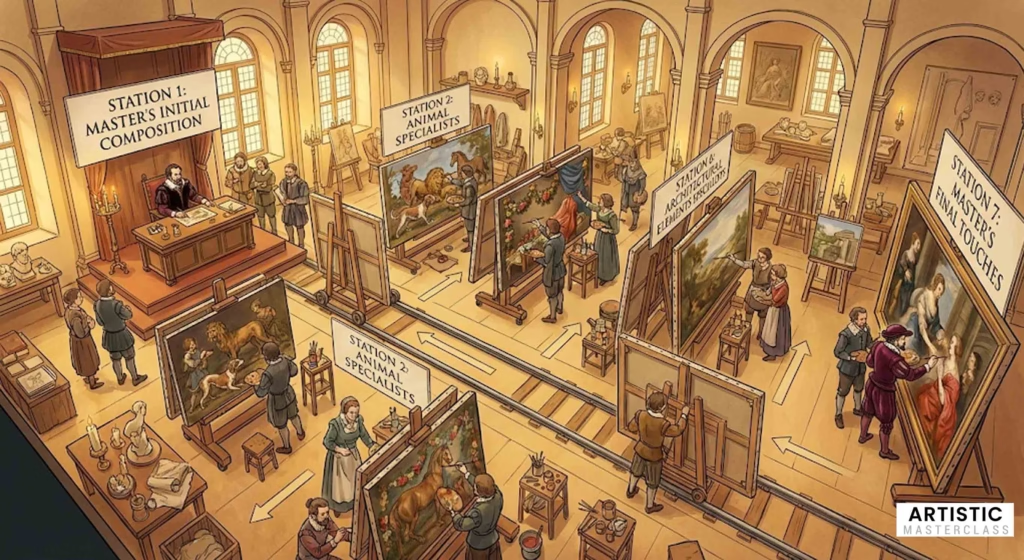

The credit system benefited masters financially and historically. Workshop output multiplied their artistic legacy. Peter Paul Rubens operated one of 17th-century Europe’s largest workshops, producing works at a pace impossible for one man. Rubens would sketch compositions, paint key elements (faces, hands, central figures), then assign the rest to specialized assistants. One might excel at painting animals, another at drapery, a third at landscapes. Rubens signed everything.

For assistants, this created a historical erasure that scholars still struggle to correct. Many paintings bear attributions like “School of Raphael” or “Workshop of Titian”—acknowledgments that assistants made substantial contributions, though their specific identities are lost. Modern technical analysis using x-rays and infrared imaging reveals multiple hands in works attributed to single masters, but we can rarely identify which assistant painted which section.

The most talented assistants left subtle signatures. Some adopted their master’s style so completely that centuries later, experts still debate attributions. Others developed recognizable individual touches visible to trained eyes. Still, historical records rarely preserved their names beyond workshop account books.

Famous Renaissance Assistants: Success Stories and Survivorship Bias

The Renaissance artist lineage reads like an artistic family tree. Leonardo da Vinci began as Andrea del Verrocchio’s apprentice around age 14 in Florence. Verrocchio’s workshop was a training ground for extraordinary talent—Pietro Perugino and Sandro Botticelli also studied there. Leonardo absorbed everything: painting, sculpture, anatomy, engineering. By his mid-twenties, he had surpassed his master.

Perugino established his own successful workshop in Perugia, where a young Raphael apprenticed in the late 1490s. Raphael learned Perugino’s graceful style so thoroughly that his early works are sometimes indistinguishable from his master’s. But Raphael didn’t stop there. Moving to Rome, he built a massive workshop of his own, employing numerous assistants to help execute papal commissions.

Among Raphael’s assistants was Giulio Romano, who painted substantial portions of the Vatican frescoes under Raphael’s direction. When Raphael died suddenly in 1520 at age 37, Romano completed unfinished commissions and went on to become a celebrated artist in his own right.

These success stories create survivorship bias. We remember Leonardo, Raphael, and Romano because they achieved independence and fame. But what about the talented assistants who never escaped the workshop system? What about those who died young from disease, or couldn’t afford guild fees, or lacked the patronage connections necessary to launch independent careers?

Historical records occasionally preserve names without artworks. Account books list assistants by name, recording their wages and years of service, but their paintings remain anonymous within the workshop’s attributed output. Thousands of talented individuals spent lifetimes creating art that enriched masters’ reputations while their own skills went unrecognized.

The system worked well for those at the top. Masters trained the next generation while multiplying their own production. But it established a pattern that would repeat across centuries: the famous take credit and profit while assistants remain invisible.

Gender and the Workshop: Women’s Double Invisibility

If male assistants faced historical erasure, women assistants confronted double invisibility. Systematically excluded from workshops by guild regulations and social norms, those who managed to create art often had their work attributed to male relatives or disappeared entirely from historical records.

Barriers to Entry: How Women Were Systematically Excluded

Renaissance guilds—the organizations controlling who could legally produce and sell art—generally prohibited women from membership. In Florence, Venice, Rome, and other major art centers, guild membership was essentially required to operate a workshop or accept commissions. Without it, artists couldn’t legally sell their work at market value or train apprentices.

Social conventions reinforced these legal barriers. The idea of young women working in workshops alongside young men was considered improper. Parents wouldn’t send daughters to male masters’ studios. Masters hesitated to accept female apprentices who might “disrupt” the all-male environment. The live-in apprenticeship model—common for boys—was deemed entirely inappropriate for girls.

Women had virtually no access to formal artistic training outside family connections. Public art academies that later emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries initially excluded women entirely. The Académie Royale in Paris, founded in 1648, didn’t admit women until 1770 and then limited them to four members total. Women couldn’t attend anatomy classes where live nude models posed—essential for learning to paint the human form. They were barred from drawing classes with male students.

The few women who became skilled artists almost always accessed training through male family members. If your father was a painter, he might teach you in his workshop. If your brother was a sculptor, you might learn alongside him. Otherwise, wealthy women could hire private tutors for “accomplishment” training—painting as a ladylike skill rather than professional craft.

This systematic exclusion created a self-perpetuating cycle. Since women rarely became established artists, there were few female masters to train the next generation. The workshop system, designed to pass knowledge from master to apprentice, locked women out almost entirely.

Access Through Family: The Daughter-Assistant Path

Despite barriers, some women accessed workshops through family connections, though even success stories often ended in erasure or tragedy.

Marietta Robusti (1560-1590), daughter of the great Venetian painter Jacopo Tintoretto, worked actively in her father’s workshop. Historical sources report she dressed in boys’ clothing to move freely in the male-dominated studio environment. She became such a skilled portrait painter that she received invitations to imperial courts, including from Spanish King Philip II and Austrian Emperor Maximilian II.

Yet only one painting is securely attributed to her today. Marietta died in her early thirties, possibly in childbirth, and much of her work was likely absorbed into her father’s attributed oeuvre. Her story illustrates both opportunity and limitation: family access opened doors, but even talented women struggled to establish independent artistic identities.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656) trained in her father Orazio’s Roman workshop and became the first woman admitted to Florence’s prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in 1616. But her path was marked by trauma. In 1611, she was raped by her father’s colleague Agostino Tassi. The subsequent public trial—where Artemisia was tortured to “verify” her testimony—became infamous.

Despite this, Artemisia built a successful career painting powerful biblical and mythological scenes featuring strong women. Her “Judith Slaying Holofernes” depicts the biblical heroine beheading the enemy general with visceral intensity. Some scholars interpret this as “visual revenge” for her rape, though others emphasize it simply demonstrates her skill at portraying strong female figures.

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), daughter of painter Prospero Fontana, established a workshop in Bologna and became one of Renaissance Europe’s most successful female artists. She painted altarpieces, portraits, and mythological scenes, supporting her husband (also an artist) and eleven children through her commissions. She even became official painter to the papal court in Rome.

Yet all three women—Robusti, Gentileschi, Fontana—succeeded only because fathers taught them. Women without artist fathers had virtually no path to professional training.

Sexual Dynamics and Exploitation: The Mistress-Assistant

When women did work closely with male artists outside family relationships, sexual dynamics complicated professional relationships, often with devastating consequences for the women involved.

Camille Claudel (1864-1943) entered sculptor Auguste Rodin’s orbit in the 1880s when she was a student and he was already established. She quickly became his assistant, lover, and artistic collaborator. For nearly fifteen years, they worked intimately together. Claudel’s talent was extraordinary—her sculptures display remarkable technical skill and emotional depth.

But the relationship’s power imbalance poisoned everything. Rodin refused to leave Rose Beuret, the mother of his son, to marry Claudel. Scholars debate how much Claudel contributed to works bearing only Rodin’s signature. Some suggest she worked on pieces like “The Gates of Hell” and various figures later attributed solely to Rodin.

The relationship ended badly around 1898. Claudel’s mental health deteriorated. She became convinced Rodin was stealing her ideas and sabotaging her career. Whether these fears reflected real exploitation or mental illness (or both) remains debated. In 1913, her family had her committed to a psychiatric institution, where she remained until her death thirty years later.

Only recently has art history fully recognized Claudel’s independent genius. For decades, she was known primarily as “Rodin’s mistress” rather than a significant sculptor in her own right. Her story exemplifies how women in art faced not just exclusion but also exploitation, with their contributions absorbed into more famous men’s legacies.

Lydia Delectorskaya (1910-1998) began working for Henri Matisse in 1932, initially as his wife’s nurse, then as his model and studio assistant. Their relationship—whether romantic or simply intensely artistic—created scandal and contributed to Matisse’s separation from his wife. Delectorskaya remained with Matisse until his death in 1954, assisting with his famous paper cut-outs and late works.

Unlike Claudel, Delectorskaya received some recognition. Matisse acknowledged her contributions to organizing his studio and materials. After his death, she became a guardian of his legacy, helping establish the Matisse Museum in Nice. Yet questions linger about the extent of her creative input versus purely assistive role.

These relationships reveal how women’s artistic labor existed in spaces between assistance, collaboration, and exploitation. When power dynamics are unequal and credit systems opaque, separating mentorship from exploitation becomes impossible.

Rare Workshop Owners: Women Who Broke Through

A tiny number of women overcame barriers to establish independent careers, though even their successes came with caveats.

Judith Leyster (1609-1660) achieved something remarkable: in 1633, she became the first woman admitted to Haarlem’s Guild of St. Luke. This gave her legal authority to operate her own workshop and hire apprentices—male apprentices. She created dynamic genre scenes and portraits in the Dutch Golden Age style, with energetic brushwork and lively compositions.

After her death, her reputation was systematically erased. Art collectors and dealers covering her signatures on paintings to fraudulently pass them off as works by Frans Hals, whose paintings commanded much higher prices. Hals’ work did resemble Leyster’s style—they painted in the same city during the same period—but the fraud was deliberate economic exploitation.

Only in the late 19th century did scholars rediscover these forgeries and restore proper attributions. Modern analysis reveals that Leyster was a skilled and prolific artist who deserved recognition in her own time. Instead, her work enriched others who sold it under a famous man’s name.

Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588), a Florentine nun, was entirely self-taught. Working within convent walls, she painted religious frescoes and panels, becoming the first known woman to paint the Last Supper. Since convents restricted contact with the outside world, her fellow nuns served as her only models—art critics noted the distinctly feminine appearance of her male figures.

Giorgio Vasari, the great Renaissance art historian, mentioned Nelli in his influential “Lives of the Artists”—one of very few women he included. Yet most of her work has been lost or remains unattributed, scattered in churches and convents with uncertain provenance.

These exceptional women proved that with talent and opportunity, women could create art equal to men’s. But their rarity underscores how effectively the workshop system excluded half the population from artistic careers.

Baroque to 19th Century: Evolution of the System

The workshop system expanded dramatically during the Baroque period (roughly 1600-1750), with some studios growing to unprecedented size and specialization. Then, in the 19th century, new artistic movements and changing economic conditions began transforming the traditional model.

Baroque Workshops as Early Art Factories

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) operated what might be called the first true art factory. His Antwerp workshop employed dozens of assistants, each specializing in specific elements. One assistant excelled at painting animals and would paint all the dogs, horses, and livestock in Rubens’ compositions. Another specialized in flowers and decorative elements. A third handled drapery and fabric. Others focused on landscapes or architectural backgrounds.

Rubens himself would create the initial oil sketch—establishing composition, color scheme, and overall design. He’d assign sections to specialists, then return to paint the most important elements: faces, hands, and anything requiring his distinctive dramatic touch. Finally, he’d sign the completed work as entirely his own.

This division of labor allowed Rubens to accept more commissions than any single artist could possibly execute. He produced altarpieces, mythological scenes, portraits, and decorative cycles at astonishing speed. His workshop’s efficiency made him wealthy and enabled him to serve simultaneously as a diplomat for the Spanish Netherlands.

Assistants who trained under Rubens often became successful artists themselves. Anthony van Dyck worked in Rubens’ workshop before establishing his own illustrious career as a portrait painter, eventually becoming court painter to King Charles I of England.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) also ran a large workshop during his successful years in 1630s-40s Amsterdam. He took on numerous pupils and employed assistants to help meet commission demands. Some of these assistants copied Rembrandt’s works, creating versions for the market. Others collaborated on paintings where Rembrandt would paint central figures while assistants handled backgrounds.

This practice creates ongoing attribution challenges. Scholars still debate which “Rembrandt” paintings were entirely by his hand versus substantially completed by assistants. Modern technical analysis reveals multiple hands in works long attributed solely to Rembrandt. The economic reality persists: a painting definitively by Rembrandt himself commands millions more than one identified as “workshop of Rembrandt” or “attributed to Rembrandt.”

The Baroque workshop system represented workshop labor at maximum scale and efficiency. Yet credit and compensation remained concentrated at the top. Masters became wealthy and famous while assistants remained largely anonymous, paid modest wages for skilled labor that enriched their employers.

The Romantic Era Shift: Emergence of the Solitary Artist Myth

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Romanticism fundamentally changed how Western culture viewed artists and art-making. The movement celebrated individual genius, emotional expression, and the artist’s unique personal vision. This philosophy conflicted with collaborative workshop production.

Romantic ideology valued “the artist’s hand”—the idea that authentic art required direct, personal execution by the creative genius. Workshop production seemed mechanical, inauthentic, even fraudulent by this new standard. The artist should express their inner vision directly through their own hands touching canvas or stone.

This shift diminished (but didn’t eliminate) the workshop system. Artists began working in smaller studios with fewer assistants. The emphasis moved toward individual style—the unique way an artist applied paint or carved stone—rather than shared workshop techniques.

Academic training also began replacing traditional apprenticeship. Art academies in Paris, London, Rome, and other cities offered formal instruction in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and art history. Students attended classes rather than living in masters’ workshops. They learned theory alongside technique.

The Impressionists, emerging in the 1860s-70s, largely abandoned workshop production. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro worked individually, emphasizing personal vision and spontaneous observation. Their paintings celebrated visible brushwork—you could see the individual artist’s hand at work.

But even in this era of supposed individualism, assistants didn’t disappear entirely. Artists still employed models, studio managers, and assistants for practical tasks. The assistance simply became less visible, less openly acknowledged, because it contradicted the Romantic myth of solitary genius.

This created a new form of invisibility. Where Renaissance and Baroque artists openly acknowledged workshop systems (even while claiming sole authorship), 19th and 20th century artists often obscured assistance to maintain the fiction of complete individual creation.

19th Century Women Artists: Still Battling for Access

Even as workshop systems declined, women continued facing systematic barriers to artistic training and careers.

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) wanted to study art at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, but her family opposed her professional ambitions. She persisted, studying at the Academy, then moving to Paris where she had to seek private instruction since the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts excluded women.

Cassatt eventually joined the Impressionists and became the only American to exhibit with the group. She developed a distinctive style featuring mothers and children in intimate domestic scenes. Her work sold well and she became financially successful—a rare achievement for any woman artist of her era.

Yet throughout her career, Cassatt criticized the art world’s systematic sexism. She observed that female artists often had to flirt with or befriend male patrons to advance—a requirement male artists didn’t face. She refused to play this game, relying instead on talent, determination, and gradually built reputation.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) became one of the most famous artists of the 19th century, achieving success unusual for any artist regardless of gender. She specialized in animal paintings, particularly horses, executed with remarkable anatomical accuracy and dynamic energy.

To study animal anatomy, Bonheur obtained police permission to wear men’s clothing (legally required in 19th-century France) so she could visit slaughterhouses, horse markets, and other venues deemed inappropriate for women in dresses. She never married, living instead with her female companion Nathalie Micas for over forty years.

Bonheur’s success came despite, not because of, the art world’s structures. She succeeded through exceptional talent, strategic self-promotion, and wealthy patronage. Most women artists, lacking her resources and determination, found professional careers impossible.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), another Impressionist, received private lessons rather than academic training since women couldn’t attend official art schools. She married fellow Impressionist Eugène Manet (brother of Édouard Manet), which gave her social standing and financial security to pursue art seriously.

Even successful women artists of the 19th century navigated obstacles their male counterparts never faced. They were excluded from training institutions, barred from life-drawing classes with nude models, unable to work freely in public spaces without scandal, and constantly battling assumptions that women couldn’t create “serious” art.

The transition from workshop apprenticeship to academic training didn’t improve women’s access—academies initially excluded them just as guilds had. Only persistent activism by women artists gradually opened doors that should never have been closed.

Andy Warhol’s Factory: The Modern Turning Point

If any single moment marked a turning point in how contemporary culture understands artist-assistant relationships, it was Andy Warhol’s establishment of his studio—aptly named “the Factory”—in 1960s New York. Warhol didn’t invent assistant-based production, but he made it explicit, celebrated, and controversial in ways that set precedent for today’s art fabrication industry.

The Factory as Assembly Line: Warhol’s Revolutionary (or Not?) Approach

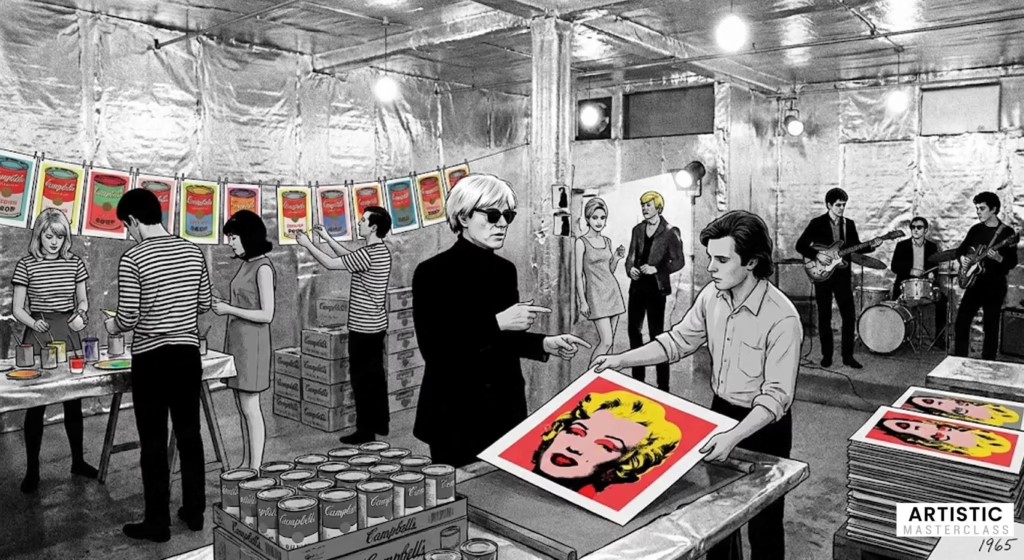

Warhol’s Factory occupied several locations during the 1960s and 70s, most famously a silver-painted loft on East 47th Street. The space functioned simultaneously as art production facility, social scene, and countercultural gathering place. It was where Warhol created his iconic works and where artists, musicians, writers, socialites, and various hangers-on mixed in a scene later mythologized as representative of 1960s avant-garde culture.

The production method was deliberate and systematic. Warhol used silkscreen printing to mass-produce images of Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and other pop culture icons. The technique allowed multiple reproductions from the same screen—challenging traditional ideas about art’s uniqueness while enabling factory-style production.

Warhol famously declared, “I want to be a machine.” He embraced mechanical reproduction, explicitly rejecting Romantic notions of the artist’s personal touch. When asked why he used silkscreens instead of hand-painting, he explained: “I tried doing them by hand, but I find it easier to use a screen. This way, I don’t have to work on my objects at all. One of my assistants or anyone else, for that matter, can reproduce the design as well as I could.”

This statement was revolutionary in its honesty. Warhol openly acknowledged that his assistants could execute the work as competently as he could. He positioned himself as idea generator and designer rather than craftsperson. The concept mattered; the execution was merely technical.

Among Warhol’s key assistants were Gerard Malanga, who printed many silkscreens and later became a poet and photographer; Ronnie Cutrone, who worked on paintings and prints; and various others who cycled through the Factory scene. Many went on to artistic careers of their own, though none achieved Warhol’s level of fame.

The Factory was also a social phenomenon. Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground rehearsed there. Actresses like Edie Sedgwick became “Warhol superstars” appearing in his experimental films. The scene mixed high art, underground culture, and sometimes dangerous drug use in ways that both reflected and influenced 1960s counterculture.

What made Warhol different from Renaissance masters wasn’t using assistants—that was centuries-old practice. What was different was his transparency. He openly acknowledged the collaborative nature of production. He embraced factory metaphors. He positioned the artist as creative director rather than craftsperson.

Critics attacked this approach as fraudulent, inauthentic, and a degradation of art. Defenders argued Warhol was honestly reflecting contemporary mass production culture while challenging outdated Romantic myths about artistic genius.

Duchamp’s Influence: Readymades and Conceptual Art

Warhol’s approach built on foundations laid by Marcel Duchamp decades earlier. In 1917, Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal—titled “Fountain” and signed “R. Mutt”—to an art exhibition. The piece was rejected, but it became one of modern art’s most influential works.

Duchamp’s “readymades”—manufactured objects presented as art—forced fundamental questions: What makes something art? Is it the artist’s manual skill or their conceptual decision? If an artist selects and designates an object as art, does that make it art regardless of who manufactured it?

These questions provided philosophical justification for artists employing fabricators. If Duchamp could sign a urinal and call it art, why couldn’t contemporary artists sign works fabricated by assistants? The concept—the artistic decision—mattered more than the execution.

This conceptual approach became foundational for contemporary art. Artists like Sol LeWitt created “instructions” for wall drawings that others would execute. Carl Andre arranged factory-made bricks in geometric patterns. Donald Judd designed minimalist sculptures manufactured by industrial fabricators.

The movement validated artist-as-designer rather than artist-as-maker. It distinguished creative vision from technical execution. And it opened the door for contemporary studios operating more like design firms than traditional workshops.

From Factory to Contemporary Fabrication

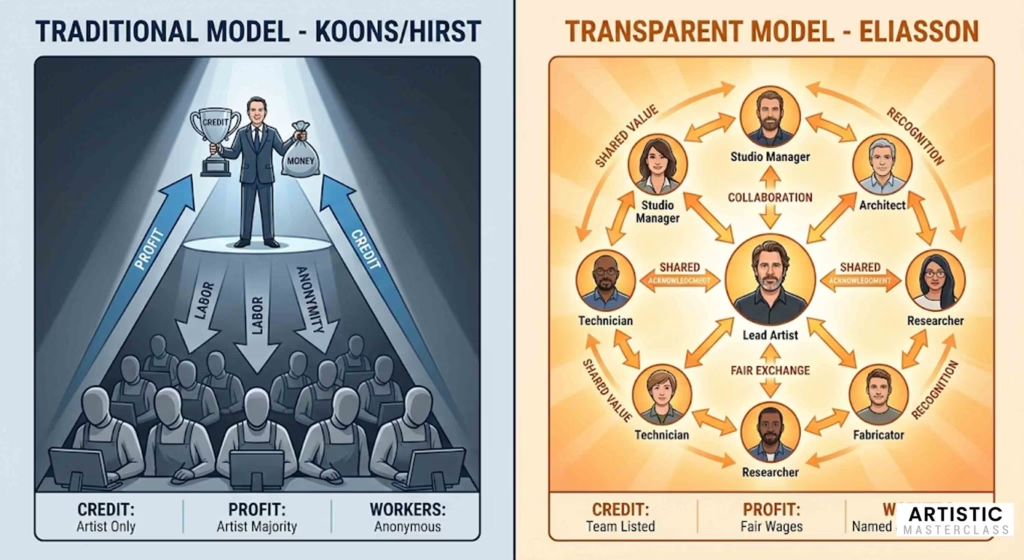

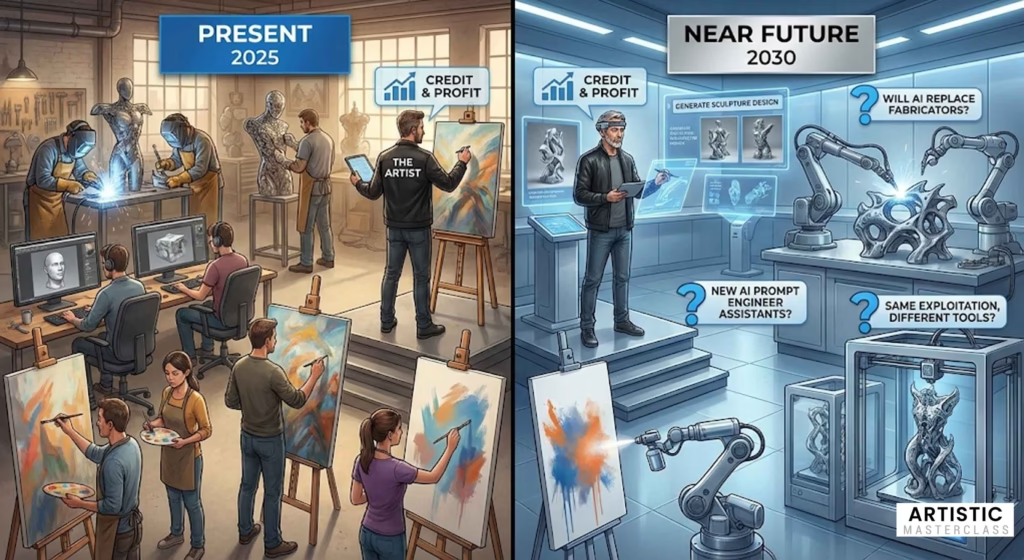

Warhol’s Factory model set precedent for how many successful contemporary artists structure their practices. The scale has increased—where Warhol had dozens of assistants, artists like Jeff Koons employ hundreds—but the fundamental model remains: the famous artist provides concepts and designs while teams execute production.

Technology has changed assistant work dramatically. Contemporary assistants use 3D modeling software, CNC machines, digital photography, and other advanced tools. The work is less about grinding pigments and more about operating sophisticated equipment. But the hierarchical structure persists: famous artist at the top, anonymous fabricators below.

The art market has embraced this model because it works economically. Successful artists can produce more work, generating more sales and gallery commissions. Collectors accept—even celebrate—works they know were fabricated by assistants, as long as the famous artist’s name is attached.

What Warhol made explicit in the 1960s has become standard practice today. The question is whether contemporary transparency actually improves conditions for assistants or simply makes old exploitation more visible.

Contemporary Controversies: The Art Fabrication Industry

Today’s art fabrication system operates at industrial scale. Major contemporary artists employ teams ranging from dozens to hundreds, creating works selling for millions while assistants earn modest hourly wages. The controversies this creates echo across art world discourse, raising persistent questions about authorship, authenticity, and economic justice.

Jeff Koons: The “Idea Person” as Artistic Identity

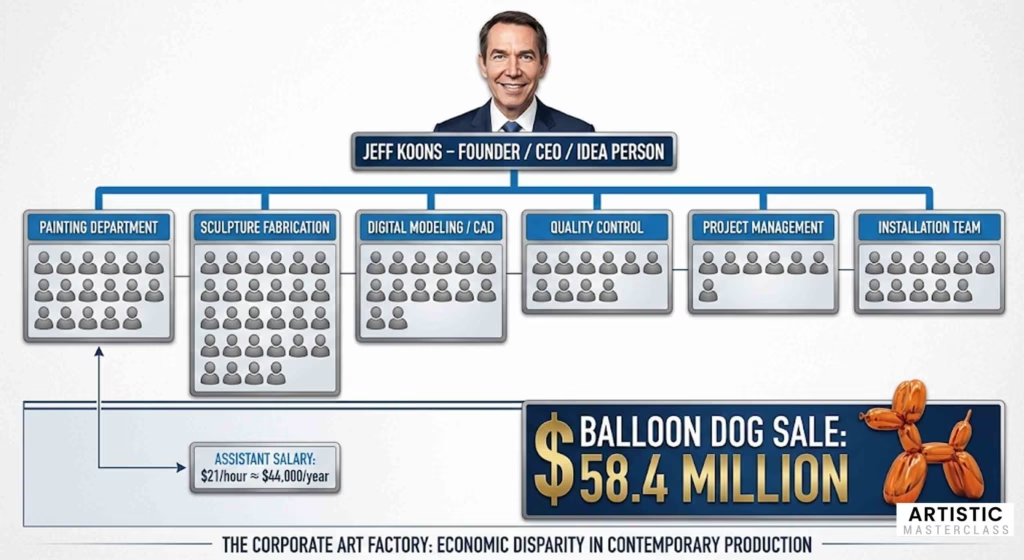

Jeff Koons represents the most extreme example of assistant-based production in contemporary art. His Chelsea studio employs over 150 people organized into specialized departments. Some focus on painting, others on sculpture fabrication, still others on digital modeling and computer graphics. Each is a specialist in one refined skill.

The production system is systematic and controlled. For his famous “Balloon Dog” sculptures, Koons provided the concept—a monumental stainless steel sculpture mimicking a twisted balloon animal. His team created 3D models, fabricated the steel components, welded and polished the structures, and applied the mirror-finish surface. The entire process took years and involved dozens of people.

For paintings, Koons developed what former assistants describe as a “paint by numbers” system. He creates designs and provides detailed specifications. Department heads develop production methods. Assistants use stencils to apply paint in predetermined patterns. The finished works bear Koons’ signature alone.

Koons openly acknowledges he doesn’t personally fabricate most of his work. In interviews, he’s stated: “I’m basically the idea person. I’m not physically involved in the production. I don’t have the necessary abilities, so I go to the top people.” He estimates that if he had to make everything himself, he might complete one painting per year. With his team, his studio produces approximately ten paintings and ten sculptures annually.

The economic disparities are stark. Assistants reportedly earn around $21 per hour—roughly $30,000-44,000 annually for full-time work. Meanwhile, one of Koons’ orange “Balloon Dog” sculptures sold for $58.4 million in 2013, setting the record (at the time) for the most expensive work by a living artist sold at auction.

Former assistants describe intense working conditions. The job requires precision and long hours. Some have described feeling like interchangeable parts in a machine. One assistant characterized the work as “paint by numbers,” suggesting limited creative input or artistic satisfaction.

Yet others defend the system. Logan De La Cruz, a painter who has worked as a Koons assistant, told reporters: “Jeff’s work is Jeff’s work. It’s not necessarily something I need to be credited on. I’m being paid to help create his vision, and that’s where I leave it… I have my own visions, and I want them to be solely mine.”

Critics, including renowned artist David Hockney, have condemned Koons’ methods. Hockney described the practice as “insulting to craftsmen, skillful craftsmen.” The implication: real art requires the artist’s hand, and industrial fabrication degrades artistic authenticity.

Defenders counter with the architectural argument: architects don’t build buildings themselves but are still credited as buildings’ creators. Film directors don’t personally film, edit, or score movies but receive creative credit. Why should visual artists be held to different standards?

Damien Hirst: Concept Over Craft, Unapologetically

British artist Damien Hirst takes an even more extreme position on assistant labor. He painted only approximately 25 of his roughly 1,400 famous “spot paintings” himself—less than 2% of the series. The rest were executed by assistants following his system.

Other major Hirst works were entirely fabricated by others:

- “For the Love of God,” the diamond-encrusted platinum skull, was created by royal jewelers Bentley & Skinner

- “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” the shark preserved in formaldehyde in a glass tank, was executed by MDM Props of London, a theater prop company

- Countless other vitrines, cabinets, and installations were designed by Hirst but fabricated by professional art fabricators

Hirst’s philosophy privileges concept over craft. He’s stated that the real creative act is the idea—the decision to create a diamond skull or preserve a shark—not the technical execution. To him, the execution is merely mechanical, requiring technical skill but not artistic vision.

His attitude is unapologetically provocative. In interviews, he’s stated he “simply doesn’t care” about criticism of his methods and “can’t be bothered” to make everything himself. This fits his persona as an art world provocateur who challenges traditional assumptions.

Yet even within Hirst’s system, tensions emerged. In a 2007 article in the Evening Standard, one of Hirst’s assistants revealed she “resented being paid £600 to do a painting that would sell for £600,000.” In an act of rebellion, she embedded a secret signature in spot paintings she created—a signature Hirst never noticed. Years later, she revealed this, exposing both her creative agency and the exploitative economics.

Rachel Howard, whom Hirst identified as “the best person who ever painted spots for me,” has established her own artistic career. But she remains better known for her association with Hirst than for her independent work—another form of overshadowing.

Hirst’s defenders argue his approach is intellectually honest about art production realities. His critics see pure exploitation: wealthy artist profiting from others’ labor while offering neither fair compensation nor proper credit.

Takashi Murakami: The Japanese Factory Model

Japanese artist Takashi Murakami, sometimes called the “Warhol of Japan,” operates a studio system explicitly modeled on anime and manga production houses. His company, Kaikai Kiki, functions as both art production facility and artist management company.

The studio employs numerous assistants who work long hours—some former assistants report days running from 8 a.m. to midnight. The culture is strict but structured, beginning each day with Japanese stretching exercises. Murakami has described his goal as merging high and low art, commercializing artistic production while maintaining quality control.

Assistants paint Murakami’s signature colorful flowers with smiling faces, his rainbow skulls, and his anime-influenced characters. They work on canvases, sculptures, and commercial products ranging from Louis Vuitton handbags to plush toys. The line between fine art and commercial merchandise blurs deliberately—part of Murakami’s conceptual project.

Crystal Chan, who worked briefly at Kaikai Kiki’s New York studio after graduating from art school in 2018, described the experience as educational despite the demanding schedule. The strict structure and long hours taught discipline and professional production standards. Yet she also noted that Murakami’s fame overshadows individual assistants’ contributions.

Murakami’s model is more transparent than Koons’ or Hirst’s about collaborative production. The anime/manga studio comparison makes the team production model explicit rather than hiding it. Yet assistants still remain largely anonymous while Murakami’s name alone commands market recognition.

Olafur Eliasson: The Transparent Alternative

Not all contemporary artists employing large teams generate controversy. Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson offers an alternative model based on transparency and explicit credit.

Eliasson’s Studio Olafur Eliasson employs approximately 90 people, including craftsmen, technicians, architects, art historians, graphic designers, filmmakers, cooks, and administrators. His website lists all team members by name, acknowledging their contributions to developing, producing, and installing artworks.

Eliasson’s philosophy explicitly rejects the solitary genius myth. He describes his practice as collaborative, stating that “co-producing culture” makes art more exciting and meaningful. His famous “Weather Project”—a massive artificial sun installation in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall—is credited as a team effort rather than solely his personal achievement.

This transparency hasn’t hurt Eliasson’s market success or critical reputation. He remains one of contemporary art’s most celebrated figures, receiving major commissions and exhibitions worldwide. His approach demonstrates that acknowledgment doesn’t diminish the lead artist’s creative role—it simply makes the process honest.

Kehinde Wiley: Outsourcing to Beijing

American painter Kehinde Wiley, known for vibrant portraits including Barack Obama’s official presidential portrait, operates a studio in Beijing where Chinese assistants help produce his paintings. The exact nature of their contributions remains deliberately ambiguous—Wiley maintains some mystery about his production process.

This outsourcing to China raises additional concerns about labor exploitation in countries with fewer worker protections and lower wage standards. Critics question whether Chinese assistants receive fair compensation and working conditions. They also note that geographic and cultural distance from Western art markets makes assistant labor even more invisible.

Wiley has defended his practice by noting that many artists throughout history have employed assistants and that his Beijing studio allows him to work at the scale and pace the art market demands. But the secrecy around exact roles and contributions contrasts with Eliasson’s transparency, suggesting discomfort with full disclosure.

The Economics of Exploitation: Following the Money

The economic structure of contemporary art production reveals stark inequalities:

Assistant Compensation:

- Entry-level assistants: $15-25/hour ($30,000-52,000 annually)

- Mid-level assistants with specialized skills: Potentially $50,000-70,000

- Department heads in large studios: Possibly $75,000-100,000+

Artwork Sale Prices:

- Major contemporary artist paintings: $50,000-500,000+

- Sculptures by artists like Koons: $1 million-$58.4 million

- Blue-chip artist works at auction: Regularly millions

Economic Example: When Hirst’s assistant was paid £600 to paint a work that sold for £600,000, she received 0.1% of the sale price. Even accounting for gallery commission (typically 50%), materials, overhead, and other costs, the ratio of assistant compensation to artwork value is minuscule.

Compare this to other creative industries:

- Film production credits all contributors (though pay disparities persist)

- Music production lists all musicians, engineers, and producers

- Book publishing lists illustrators, designers, and sometimes even editors

- Architecture firms credit project teams, not just lead architects

The visual art market operates differently. The famous artist’s name alone commands value, with assistant contributions treated as invisible overhead rather than recognized creative labor.

The Working Conditions Reality: Testimonials from Current Assistants

Contemporary assistants offer varied perspectives on their experiences, revealing both exploitation and opportunity:

Logan De La Cruz (Koons assistant): “Jeff’s work is Jeff’s work… I’m being paid to help create his vision… I have my own visions, and I want them to be solely mine.” He accepts the arrangement, viewing assistant work as paid labor separate from his personal artistic identity.

Christine Ting (Ryan McGinley photography assistant): “As a photographer, you want to be focused on shooting. You don’t want to be distracted. We’re the extra eyes, brains, and hands.” She frames assistance as necessary professional support enabling the lead photographer to concentrate on creative decisions.

Crystal Chan (former Murakami assistant): Described 8 a.m.-to-midnight days with Japanese stretching exercises, strict structure, and valuable learning. Yet she noted: “The majority of people don’t know enough to know whether [this art is] good or not. But if the media says it’s good, people will like it.”

Amy Houmøller (Ryan Gander assistant): Turned down a higher-paying assistant position because former assistants warned the artist was “so awful” that “nobody could stay in that job for long.” She chose “to be poorer but happier” with a more respectful employer.

These testimonials reveal that working conditions vary dramatically between studios. Some artists treat assistants professionally and respectfully. Others create toxic environments where turnover is high and exploitation normalized.

The pattern across testimonials: assistants generally accept not receiving credit for works they help create, viewing this as understood terms of employment. But they expect fair treatment, reasonable compensation, and professional respect. When these aren’t provided, resentment builds.

The Anonymous Ones: Assistants Who Died in Obscurity

For every assistant who became a famous artist or even received historical recognition, hundreds or thousands died with their work in museums, galleries, and private collections under other people’s names. These stories—when we can recover them at all—reveal the true human cost of the credit system’s failures.

Vladimir Dvorkin: A Fabricator’s Lost Legacy

Vladimir Dvorkin painted for decades, creating thousands of works in various styles. But every painting left his hands unsigned. Israeli artist Oz Almog would sign them, sell them, and pocket the proceeds while Dvorkin received only fabrication fees.

The arrangement wasn’t technically illegal. Dvorkin worked as an art fabricator—executing another artist’s designs for payment. Such arrangements exist throughout the contemporary art world. But the emotional and historical costs were profound.

When Dvorkin died in 2014, his paintings hung in museums and private collections worldwide, all attributed to Almog. His grandson, Roman Lapshin, discovered the truth and created a documentary called “Portrayal” investigating his grandfather’s hidden artistic legacy.

Lapshin traveled across continents confronting Almog and attempting to reclaim his grandfather’s recognition. The documentary captures his anger, grief, and frustration. “These brush strokes, no other man can ever do brush strokes like that,” he insists, arguing that his grandfather’s unique touch deserved attribution.

But legally, Dvorkin had no claim. He’d been paid for fabrication services. Art law treats such arrangements as work-for-hire—the person paying owns all rights. Morally and historically, however, questions persist: Is Almog the “artist” of paintings he never touched? Should museums relabel works as “executed by Vladimir Dvorkin for Oz Almog”?

Dvorkin’s story gained attention because his grandson fought for recognition. How many other talented fabricators died without anyone investigating their contributions? How many museum collections contain works attributed to famous names but executed by unknown hands?

The Unmarked Graves: Renaissance Assistants Who Never Became Masters

Renaissance workshop records occasionally preserve assistant names in account books and contracts. But most of these individuals remain historical ghosts—we know they existed, but nothing else.

Consider an anonymous assistant in Raphael’s workshop. He trained for years, learned to mix colors and prepare panels, developed skill at painting drapery and architectural backgrounds. Perhaps he painted substantial portions of Vatican frescoes tourists admire today. But he never completed his masterpiece, never joined the guild, never established his own workshop. Maybe he couldn’t afford the fees. Maybe he died young in one of Rome’s plague outbreaks. Maybe he simply lacked the patronage connections necessary to launch an independent career.

Hundreds or thousands of such talented individuals existed in Renaissance Italy alone. Some might have become as celebrated as Raphael or Michelangelo given different circumstances. Most disappeared into history, their contributions visible only in the problematic attribution category “School of” or “Workshop of.”

Modern art historians use technical analysis—x-rays, infrared imaging, paint chemistry—to identify different hands in works attributed to single masters. Sometimes they can determine that a painting long attributed entirely to one artist shows contributions from multiple people. But they rarely can identify which specific assistant painted which section.

Questions that cannot be answered:

- How many talented artists completed their training but couldn’t afford guild membership fees?

- How many died young from disease or accidents before achieving recognition?

- How many were skilled but overshadowed by celebrity masters, never finding their own patrons?

- How many were women whose gender excluded them from independent careers?

The fragmentary records preserve names without legacies, suggesting the scale of invisible talent erased by the credit system.

Modern Fabricators: The Contemporary Anonymous

Today’s art fabrication companies—firms like MDM Props, Carlson & Co., and Pembridge Studios—employ skilled fabricators who execute designs for multiple famous artists. These companies possess expertise in welding, casting, glasswork, and other specialized techniques that even successful artists don’t personally master.

When Damien Hirst wanted to preserve a shark in formaldehyde within a custom glass tank, he hired MDM Props. Their craftspeople designed the tank, sourced the shark, handled preservation, and assembled the piece. Hirst provided the concept and signed the finished work.

When Jeff Koons designs monumental sculptures, fabrication companies manufacture the components. Welders join steel sections. Finishers polish surfaces. Painters apply coatings. These are skilled professionals whose work quality directly impacts the finished piece’s success.

Yet when “Balloon Dog (Orange)” sold for $58.4 million, no one mentioned the fabricators’ names. The auction catalog credited only Koons. The press coverage discussed only Koons. Museum labels listing the work name only Koons.

Some fabricators are themselves artists with independent practices who work in fabrication for income. Others are professional craftspeople who’ve chosen careers in production rather than personal art-making. All deserve acknowledgment for their contributions.

One anonymous director of an art fabrication company told CBC Documentaries: “The successful ones [successful artists] are good with money: getting it and using it. They’re almost accountant types as well as artists.” His comment suggests that contemporary art success requires business acumen and capital as much as or more than artistic vision or technical skill.

Working with fabricators “frees up time to do more projects,” enabling successful artists to maximize production and sales. But the arrangement also concentrates wealth and recognition upward while distributing labor costs downward to anonymous, modestly compensated workers.

The system creates a class structure: celebrity artists earning millions, gallery owners taking large commissions, and fabricators earning hourly wages while remaining historically invisible.

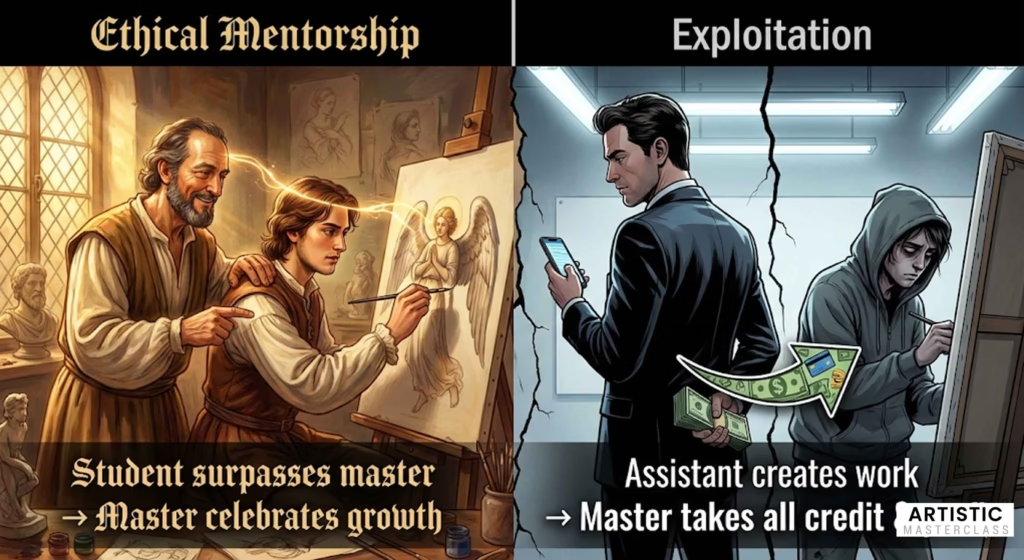

When It Goes Right: Positive Mentorship Models

Not all artist-assistant relationships are exploitative. Throughout history, some have provided genuine education, launched careers, and created mutually beneficial collaborations. Understanding these positive models offers hope for more ethical contemporary practices.

The Successful Lineage: Mentorship That Launched Careers

The Renaissance produced artistic lineages where assistants genuinely learned from masters and went on to achieve independent success.

Andrea del Verrocchio’s Florentine workshop in the 1460s-70s trained an extraordinary generation. Leonardo da Vinci, Pietro Perugino, and Sandro Botticelli all studied there, learning techniques that shaped Renaissance art. Verrocchio seems to have been a generous teacher who recognized talent and encouraged development rather than simply extracting labor.

The relationship between Verrocchio and Leonardo illustrates ideal mentorship. According to Giorgio Vasari’s account, when Verrocchio saw the angel young Leonardo painted in “The Baptism of Christ,” he recognized his student had surpassed him and stepped back to let Leonardo flourish. Whether this story is entirely true or somewhat mythologized, it represents the mentorship ideal: the master recognizing and celebrating the student’s achievement.

Pietro Perugino established his own workshop in Perugia where Raphael apprenticed in the late 1490s. Perugino taught Raphael graceful composition and clear spatial organization. Their early works are so similar that attribution debates still occur. But Perugino didn’t suppress Raphael’s development. He trained him, then let him move to Florence and Rome to find his own path.

Raphael in turn employed numerous assistants in his Roman workshop, including Giulio Romano and Giovanni da Udine. When Raphael died suddenly in 1520, Romano was skilled enough to complete unfinished commissions and launch his own successful career. Raphael had trained Romano not just to execute his designs but to think and create independently.

In the 20th century, Robert Rauschenberg’s practice included assistants Brice Marden and Dorothea Rockburne, both of whom became significant artists. Rauschenberg’s approach was collaborative and educational, creating an environment where assistants learned while contributing.

Andy Warhol’s Factory, despite its controversies, launched several careers. Gerard Malanga became a poet and photographer. George Condo developed into a successful neo-expressionist painter. These assistants gained access to the art world, learned production techniques, and built networks that supported their own practices.

The pattern in successful mentorship: masters shared knowledge generously, recognized assistants’ talents, and supported their independent development rather than viewing them as perpetual subordinates or sources of exploitable labor.

Contemporary Ethical Models

Some contemporary artists have developed practices that acknowledge assistant contributions while maintaining lead creative roles.

Olafur Eliasson’s Transparent Team Model: As discussed earlier, Eliasson lists all 90+ team members on his website and describes his work as inherently collaborative. Team members have diverse skills—from craftsmen to architects to cooks—and all contribute to the studio’s functioning. This model demonstrates that transparency and credit-sharing don’t diminish the lead artist’s reputation or market value.

University-Affiliated Artists: Some successful artists hold university teaching positions, creating a formal educational structure where students learn while assisting with projects. This frame—teacher and student rather than employer and employee—makes the educational value explicit and creates clear ethical boundaries.

Artist Cooperatives: Some artists work as collectives where credit is shared from the beginning. Groups like Guerilla Girls (feminist activist artists) or collaborative design studios operate without single-name attribution. While these aren’t traditional assistant relationships, they model alternative credit and profit-sharing systems.

Photographers Who Credit Assistants: Some photographers list assistant credits in exhibition materials or photo captions, acknowledging the team contribution to final images. While lead photographer receives primary credit, assistance isn’t invisible.

Commissioned Work with Fair Compensation: Some arrangements involve fair payment for assistant work on specific projects with clear agreements about credit and compensation. When terms are transparent, equitable, and respected, the arrangement can benefit all parties.

The key ethical elements:

- Honest acknowledgment of who does what

- Fair compensation relative to work contribution and artwork value

- Genuine educational value provided to assistants

- Clear communication about credit, ownership, and expectations

- Respect for assistants as skilled professionals

The Educational Value: What Assistants Gain Beyond Pay

Even in imperfect systems, assistant positions can provide valuable career development:

Technical Skill Acquisition: Assistants learn specialized techniques—from Renaissance pigment preparation to contemporary 3D modeling—that support their own artistic practices. The hands-on experience is often more valuable than academic instruction alone.

Professional Networks: Working in established artists’ studios provides access to galleries, collectors, curators, and other art world professionals. These connections can launch careers when assistants develop their own practices.

Production Knowledge: Assistants learn how art actually gets made at professional scale—how to organize materials, manage timelines, troubleshoot problems, and execute complex projects. This practical knowledge is essential for sustaining artistic careers.

Industry Understanding: Assistants see how the art market works: how galleries operate, how collectors make decisions, how commissions are negotiated, how pricing works. This inside knowledge demystifies an opaque industry.

Portfolio Material: Even without formal credit, assistants can list experience on CVs and discuss skills developed in job interviews. The experience signals professional competence to future employers or collaborators.

Mentorship (When Good): Some lead artists genuinely mentor assistants, offering career advice, introductions, recommendations, and guidance that extends beyond immediate job responsibilities.

The question is whether these benefits justify low pay and lack of credit, or whether they’re consolation prizes that don’t excuse exploitation. The answer likely depends on specific circumstances: how assistants are treated, whether promises of advancement are kept, and whether the educational value is real or just rhetoric justifying low wages.

Legal, Ethical, and Philosophical Dimensions

The artist-assistant debate involves intersecting questions of law, ethics, and philosophy. Understanding these dimensions reveals why easy answers don’t exist and why debates continue centuries after the system’s origins.

Intellectual Property Law: Who Owns Collaborative Work?

Current intellectual property law treats most assistant-created work as “work for hire”—creations made by employees or contractors that legally belong to whoever paid for them.

Under U.S. copyright law (and similar laws in most countries), works created by employees within the scope of employment automatically belong to the employer. The employee has no copyright claim regardless of their creative contribution. This applies to artists’ assistants just as it does to software engineers, graphic designers, or writers working for companies.

When assistants aren’t formal employees but independent contractors, copyright can be more complex. Generally, contractors retain copyright unless they sign agreements transferring it to whoever hired them. Most contemporary artist studios require assistants to sign contracts explicitly waiving all rights to anything created during their employment.

These contracts typically include non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) prohibiting assistants from discussing studio methods, designs, or their specific contributions. Breaking these agreements can result in lawsuits. This legal structure ensures assistants can’t later claim co-authorship or demand recognition.

Historical precedent supports this arrangement. Renaissance guild rules and workshop contracts gave masters ownership of all workshop output. Baroque-era agreements specified that masters owned apprentices’ work. The legal framework has always concentrated rights at the top.

Rare disputes occur when assistants claim their contributions exceeded what employment agreements covered. These cases generally fail unless assistants can prove they created works independently that were then appropriated, rather than creating works as directed for their employer.

Some countries recognize “moral rights”—legal protections for creators’ attribution and work integrity separate from economic copyright. France, Germany, and some other European nations grant creators’ rights to attribution even when copyright belongs to others. These laws could theoretically require assistant credit, but enforcement is limited and rarely applied to the artist-assistant context.

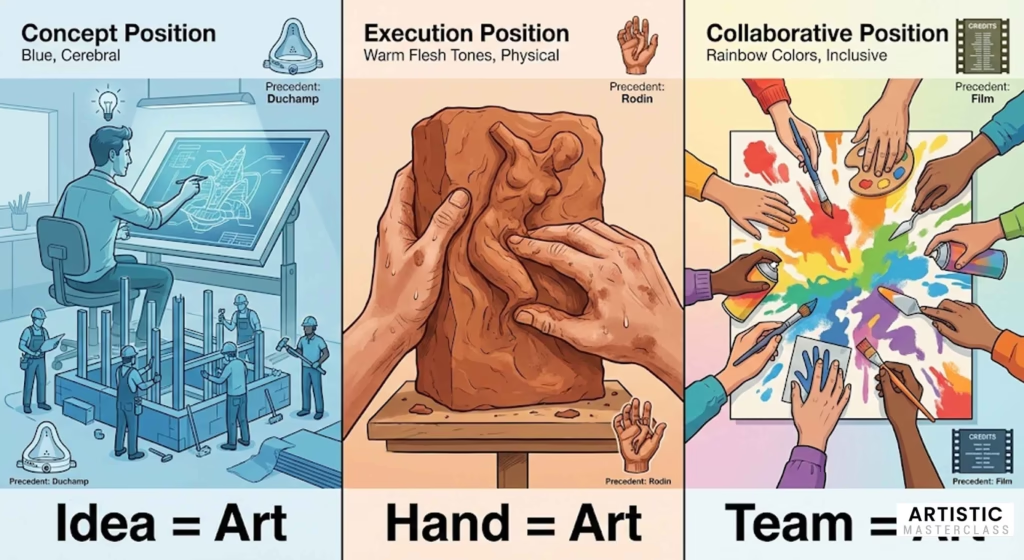

The Authorship Debate: What Makes Someone the “Artist”?

Philosophically, three main positions dominate the authorship debate:

The Concept Position: Art is fundamentally about ideas. The artist who conceives a work is its true creator, regardless of who executes it. This view privileges intellectual contribution over manual labor.

Defenders cite precedents:

- Marcel Duchamp’s readymades (the artistic act is selecting and designating, not making)

- Architectural practice (architects don’t build buildings but are credited as creators)

- Film direction (directors don’t personally film, edit, or score movies but receive creative credit)

- Conceptual art movements (Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings executed by others from instructions)

Critics argue this deskills art, devalues craft, and erases labor. It conveniently benefits those with resources to hire fabricators while dismissing the skill involved in actually making things.

The Execution Position: Real art requires the artist’s hand—direct, personal engagement with materials. Authenticity comes from the artist physically creating work, their unique touch visible in brushstrokes, chisel marks, or other signs of individual making.

Defenders cite:

- Romantic traditions valuing individual expression

- The importance of tacit knowledge (skill that can’t be fully verbalized or delegated)

- Craft traditions where making is inseparable from designing

- The personal connection between artist and artwork created through physical engagement

Critics argue this position is nostalgic and unrealistic for large-scale contemporary work. It also ignores that historical masters always used assistants, making “artist’s hand” more myth than reality.

The Collaborative Position: Art is inherently collaborative. Credit should reflect the team effort involved rather than maintaining solo artist fictions. The lead artist’s conceptual contribution deserves recognition, but so do assistants’ execution skills.

Defenders cite:

- Honesty about actual production processes (Eliasson’s model)

- Other creative industries’ crediting practices (film, music, publishing)

- The skill and creativity fabricators contribute even when following designs

- Justice and fairness in acknowledging labor

Critics argue this dilutes individual artistic vision and complicates the market. Collectors want to buy work by famous names, not committees. Shared credit might reduce artwork value while not meaningfully improving assistants’ conditions.

Each position has merit. The debate continues because the question—what is art?—admits no single answer.

The Value Question: What Are We Really Buying?

When collectors purchase art, what exactly are they buying?

The Market Perspective: Buyers are purchasing the famous artist’s name, reputation, and brand. The name guarantees value retention or appreciation. Like designer fashion, the label matters more than who actually stitched the garment.

This explains why a “Rembrandt” painting might sell for $5 million while a “Workshop of Rembrandt” brings only $500,000, even if technical analysis reveals both had similar levels of direct Rembrandt participation. The certain attribution commands premium prices.

The Collector Perspective: Some collectors care deeply about “the artist’s hand” and prefer work they believe the credited artist personally made. Others don’t care about fabrication method if they admire the concept and finished product. Preferences vary, but the market generally values famous names regardless of fabrication reality.

The Investment Perspective: Art functions as an asset class for wealthy collectors. Name recognition and established market history make artworks by blue-chip artists safer investments than work by unknown fabricators. This financial calculation reinforces the system where famous names command value.

The Authentication Issue: Museums and auction houses distinguish between certain attributions and uncertain ones. “By Rembrandt” means experts believe he painted it personally. “Attributed to Rembrandt” suggests uncertainty. “Workshop of Rembrandt” acknowledges assistants made significant contributions.

These distinctions can mean millions in value difference, creating economic incentives for certain attribution even when evidence suggests collaboration. The system rewards single-name attribution and punishes honest acknowledgment of assistance.

The Contemporary Irony: In contemporary art, everyone knows Jeff Koons doesn’t personally fabricate his sculptures and Damien Hirst didn’t paint most of his spot paintings. The fabrication method is open knowledge. Yet these works sell for millions specifically because of the artists’ names. The market values the brand more than the making.

This suggests contemporary collectors aren’t buying craftsmanship or “the artist’s hand”—they’re buying concepts, cultural significance, and investment potential associated with famous names.

Technology’s Impact: From Pigments to AI

Throughout history, technological changes have transformed assistant labor while the hierarchical structure persisted. Understanding this evolution shows how the system adapts to new tools without fundamentally changing power dynamics.

Historical Technology Shifts

Pre-Photography Era (Renaissance-1830s): Before photography, artists and their assistants were the only means of creating visual records. Assistants were essential for every painted portrait, landscape, or historical scene. Kings commissioned paintings to document their reigns. Wealthy families hired artists for portraits. Churches needed altarpieces and frescoes.

The monopoly on image-making gave artists substantial economic power. Assistants learned these essential skills through years of grinding pigments, preparing panels, and practicing drawing. The technology was entirely manual—no mechanical reproduction existed beyond printing presses for woodcuts and engravings.

Photography’s Invention (1839): The daguerreotype and subsequent photographic technologies revolutionized image-making. Suddenly, accurate visual records could be created mechanically, faster and cheaper than painting. Portrait painting’s market collapsed as photography offered affordable alternatives.

This created new assistant roles. Photographers employed darkroom technicians to develop plates and prints—skilled work but different from traditional artistic training. Some painting studios declined as demand shifted. Assistants needed new technical skills to remain employed.

Industrial Materials (19th-20th centuries): Manufactured paints in tubes (invented mid-1800s) replaced hand-ground pigments. Pre-stretched canvases became commercially available. These conveniences reduced some assistant tasks while enabling artists to work outside studios more easily (contributing to Impressionist outdoor painting).

New materials like steel, plastics, and industrial chemicals created opportunities for artists working at architectural scale. This required new assistant skills: welding, chemical handling, industrial fabrication techniques. Assistants became more like factory workers than traditional artisans.

Mechanical Reproduction (20th century): Printing presses, lithography, and later silkscreen printing (perfected by Andy Warhol) enabled mass reproduction. Photography, photomechanical reproduction, and digital printing further expanded possibilities.

These technologies made assistant labor more mechanical. Warhol’s assistants operated silkscreen presses rather than hand-painting. The work became more repetitive and less individually skilled, though still requiring precision and training.

Digital Revolution and Contemporary Fabrication

Contemporary art production employs technologies unimaginable to Renaissance masters:

3D Modeling Software: Assistants use CAD (Computer-Aided Design) programs to create digital models of sculptures. Software like Rhino, SolidWorks, or Maya allows precise three-dimensional design that can be modified, scaled, and refined before any physical fabrication begins.

An assistant trained in 3D modeling might spend weeks refining a digital sculpture, adjusting curves and surfaces to match the artist’s vision. This requires high-level technical skill—arguably as sophisticated as traditional sculpture but different in character.

CNC Machining: Computer Numerical Control machines can cut, carve, and shape materials with precision impossible by hand. An assistant programs cutting paths, loads materials, monitors the machine, and handles finishing work.

CNC machining allows sculptors to create complex forms at scales previously impossible. But the assistant’s role shifts from manual carving to programming and machine operation—still skilled work, just different skills.

3D Printing: Additive manufacturing builds objects layer by layer from digital files. Contemporary artists use 3D printing for prototypes, finished sculptures, and complex geometric forms. Assistants manage printers, prepare files, handle post-processing (removing support structures, surface finishing).

Digital Photography: Modern photography is almost entirely digital. Assistants handle memory cards instead of film, use Photoshop instead of darkrooms. The technical skills are different but equally essential. Photo retouching and digital compositing require hours of skilled computer work.

Laser Cutting, Water Jets, Robotic Arms: Advanced fabrication tools enable precise material processing. Each requires trained operators—contemporary assistants need programming skills, mechanical knowledge, and safety training.

The pattern: technology changes tools but maintains hierarchies. Contemporary assistants need advanced technical education (often college degrees in digital design, engineering, or related fields) rather than traditional artistic apprenticeship. But they still work for famous artists, receive hourly wages, and remain largely anonymous.

AI and the Future of Assistants

Artificial intelligence now generates images from text descriptions, raises new questions about artistic labor’s future.

Current AI Capabilities:

- Text-to-image AI (like DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion) creates images from prompts

- AI can generate artwork in various styles

- Some artists experiment with AI as a creative tool

- AI-generated art wins competitions and sells at auction

Questions for Assistant Labor:

- Will AI replace human fabricators?

- If AI can execute artistic visions from descriptions, does that strengthen the “artist as idea person” argument?

- Or will handmade work become more valuable by contrast with AI-generated work?

Likely Reality: AI will create new assistant roles rather than eliminating them. Someone needs to write effective prompts, select among AI outputs, refine results, and integrate AI elements into larger works. These become new forms of skilled assistance.

Large-scale sculpture, installation, and physical fabrication still require human hands. AI can design, but physical making requires human skill (at least until robots become far more sophisticated).

The fundamental pattern will likely persist: famous artists will employ assistants with new technical skills (AI prompting, output curation, integration) while maintaining the credit and compensation hierarchy.

Technology continually changes what assistants do but rarely changes their position in the system.

What Has Changed, What Hasn’t: Patterns Across 600 Years

After tracing the hidden labor of artist’s assistants from 1400 to 2025, certain patterns emerge—elements that persist despite dramatic changes in art styles, production technologies, and cultural contexts.

What Persists: Unchanging Realities

Credit Appropriation: From Renaissance workshops to contemporary fabrication studios, the famous artist’s name alone appears on finished work. This hasn’t changed in 600 years despite dramatically different production contexts.

Whether Rembrandt signing paintings his assistants executed or Jeff Koons signing sculptures his team fabricated, the pattern remains: one name gets historical credit while many hands create the work.

Economic Exploitation: Assistants have always been underpaid relative to artwork value. Renaissance apprentices often worked for room and board alone. Contemporary fabricators earning $21/hour create works selling for millions. The ratio of assistant compensation to artwork value remains minuscule across centuries.

Masters and famous artists consistently profit enormously while assistants receive subsistence or modest wages. The economic structure concentrates wealth upward and distributes labor costs downward.

Gender Barriers: Women have always faced additional obstacles in art production. Renaissance guilds excluded them. Baroque workshops rarely admitted them. Academic training denied them access. Contemporary art markets still undervalue them.

Though conditions have improved (women can now attend art schools, join professional organizations, and achieve recognition), they remain underrepresented among top-earning artists and face persistent discrimination. Women assistants experience both labor exploitation and gender-based barriers.

Invisibility: Most assistants throughout history remain unknown. We have fragmentary names in Renaissance account books but no attributed works. We know fabrication companies execute contemporary sculptures but not which individual welders worked on what pieces. Historical erasure is the norm, recognition the rare exception.

Training Justification: From the beginning, the system was justified as education. Apprentices accepted low wages and hard work because they were “learning.” Contemporary assistants accept modest compensation because the experience provides “professional development.” The rhetoric hasn’t changed even as actual educational value varies wildly.

Power Imbalance: The famous artist holds all leverage in the relationship. They control hiring, firing, wages, working conditions, and whether any acknowledgment occurs. Assistants have minimal negotiating power unless they’re exceptionally skilled or willing to walk away from rare opportunities.

What Has Changed: Genuine Evolution

Scale: Renaissance workshops employed 5-20 people. Baroque workshops might have 20-30. Warhol’s Factory had dozens. Jeff Koons employs over 150. The number of people involved in creating work attributed to single artists has expanded dramatically.

Contemporary fabrication operates at industrial scale impossible in pre-modern eras. This makes coordination more complex but also makes individual assistant contributions more invisible within vast teams.

Transparency: Renaissance masters openly acknowledged workshop systems even while claiming sole credit. The 19th century Romantic movement obscured assistance to maintain solitary genius myths. Warhol explicitly celebrated factory production. Contemporary artists vary from complete transparency (Eliasson) to deliberate secrecy (Wiley).