Scroll through TikTok on any given day and you’ll encounter vastly different worlds existing side-by-side. A creator forages for mushrooms in an overgrown forest, carefully documenting each species with muddy hands and genuine delight. Another films themselves baking sourdough in a sun-drenched cottage kitchen, the camera lingering on vintage floral aprons and handmade pottery. A third posts surreal digital art—distorted childhood imagery layered with cryptic text and an unsettling oversized eye watching from the corner.

These aren’t random hobbies or passing trends. They’re visual languages, identity statements, and entry points into thriving niche online art communities. Cottagecore, Goblincore, and Weirdcore represent three of the most influential internet aesthetics to emerge in the 2020s—movements that transformed how Gen Z creates, shares, and understands art in digital spaces.

This guide explores how these aesthetics evolved from simple visual styles into genuine cultural movements, examining their origins on Tumblr, their explosion during the pandemic, and their lasting impact on digital art, identity formation, and contemporary culture. You’ll discover not just what these aesthetics look like, but why they matter—psychologically, artistically, and culturally—and how they’ve fundamentally changed the relationship between art, community, and self-expression online.

Understanding Internet Aesthetics as Art Communities

Before diving into specific aesthetics, we need to understand what makes internet aesthetics different from traditional art movements or simple fashion trends. These aren’t passive visual preferences—they’re active creative communities with their own artistic practices, value systems, and methods of cultural production.

From Consumption to Creation: The Shift in Online Art Culture

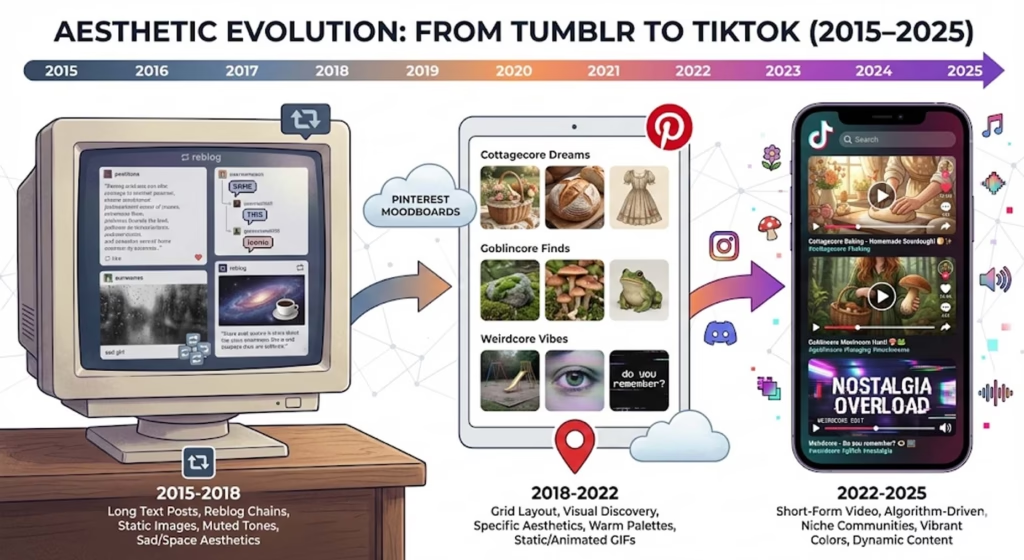

The evolution from Pinterest moodboards to TikTok creation marks a fundamental shift in how people engage with visual culture online. On Pinterest, users collected and curated existing images, building aspirational boards of homes they’d never own and lives they’d never lead. The platform encouraged passive consumption—scrolling, saving, dreaming.

TikTok flipped this dynamic. The duet feature, stitch function, and sound-sharing tools transformed viewers into collaborators. When someone posts a Cottagecore baking tutorial, dozens of creators respond with their own versions, iterations, and reinterpretations. The algorithm rewards creation over curation, participation over observation. You don’t just admire Goblincore mushroom photography—you grab your phone, head to the nearest park, and start documenting fungi yourself.

This shift mirrors broader changes in digital culture. Where early internet culture separated “creators” from “consumers,” platforms like TikTok, Tumblr, and Discord have blurred these boundaries completely. Everyone’s an artist; everyone’s an audience. The niche online art communities that emerged from this shift aren’t about following established artists—they’re about collective creation where the community itself becomes the artist.

The “-Core” Phenomenon: More Than Aesthetic Labels

Walk through any comment section on TikTok and you’ll encounter a dizzying array of “-core” labels: Cottagecore, Goblincore, Weirdcore, Dreamcore, Kidcore, Traumacore, Normcore, Gorpcore. The suffix has become internet shorthand for “this aesthetic exists as a distinct thing.”

The term’s origins trace back to hardcore punk in the 1980s, where “-core” denoted music subgenres (metalcore, grindcore, emocore). Over time, it migrated to fashion (normcore in 2013), then exploded across internet culture in the late 2010s. By 2020, you could add “-core” to almost any noun and instantaneously signal a specific aesthetic universe.

But these labels do more than categorize visuals. They create communities. When someone identifies as “Goblincore,” they’re not just saying “I like earthy colors and mushrooms.” They’re signaling values (anti-consumerism, neurodivergent acceptance), creative practices (foraging, found object art), and a way of being in the world. The label becomes an identity framework—a shorthand for finding your people in the vastness of the internet.

This naming power explains why internet aesthetics proliferate so rapidly. Creating a new “-core” doesn’t require institutional validation or art world gatekeepers. A single viral TikTok can birth an entire movement. The community, not critics or curators, decides what constitutes a legitimate aesthetic.

Platform Dynamics: From Tumblr to TikTok

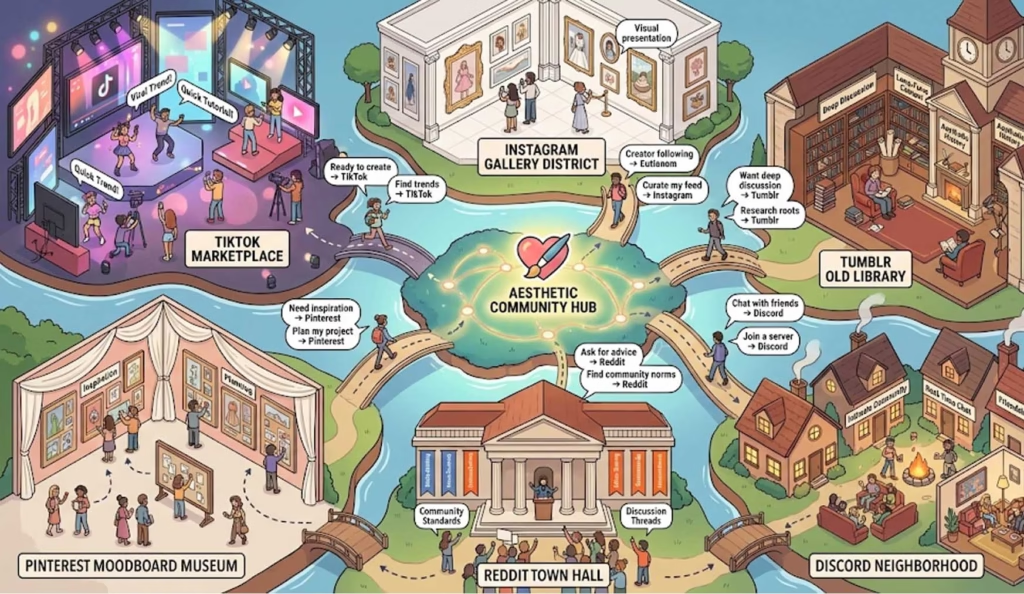

To understand how niche online art communities function today, you need to understand the platforms that shaped them. Each social media environment creates different conditions for creative expression and community formation.

Tumblr, dominant in the early-to-mid 2010s, offered reblog culture, long-form text, relative anonymity, and algorithmic obscurity. Communities formed slowly, organically, through chains of reblogs and careful tagging. You could build an entire aesthetic identity on Tumblr without your real-life friends ever knowing. The platform rewarded curation, mood, atmosphere—building immersive digital worlds through collected imagery and poetic captions. Early Cottagecore emerged here, alongside Soft Grunge, Pastel Goth, and dozens of other microaesthetics.

TikTok, exploding in 2019-2020, brought algorithmic discovery, video-first creation, and rapid viral spread. The For You Page showed you content based on engagement patterns, not just who you followed. This meant niche communities could find each other instantly. A single video about collecting shiny rocks could connect you to thousands of Goblincore enthusiasts overnight. The platform’s design—short videos, trending sounds, easy duets—encouraged immediate participation rather than contemplative curation.

This platform migration fundamentally changed internet aesthetics. Where Tumblr communities developed slowly and stayed somewhat underground, TikTok aesthetics explode into mainstream consciousness within weeks. Cottagecore went from niche Tumblr tag to New York Times coverage in months. This visibility brings both opportunity (more creators, more art) and tension (commercialization, appropriation, dilution of original values).

Instagram sits somewhere between, offering visual polish and aspirational lifestyle content. Pinterest remains the moodboard capital, gathering aesthetic inspiration but rarely generating new movements. Discord provides the intimate community spaces where aesthetic communities actually talk, plan, and build relationships beyond performing for algorithms.

Understanding these platform dynamics explains why certain aesthetics thrive in certain spaces—and why the communities themselves shape their artistic output based on where they gather.

The Cultural Context: Why Now?

The rise of Cottagecore, Goblincore, and Weirdcore wasn’t random. These aesthetics emerged in response to specific cultural, economic, and psychological conditions of the early 2020s. They’re coping mechanisms, identity frameworks, and artistic movements born from particular anxieties and yearnings of our current moment.

Pandemic Escapism and Control

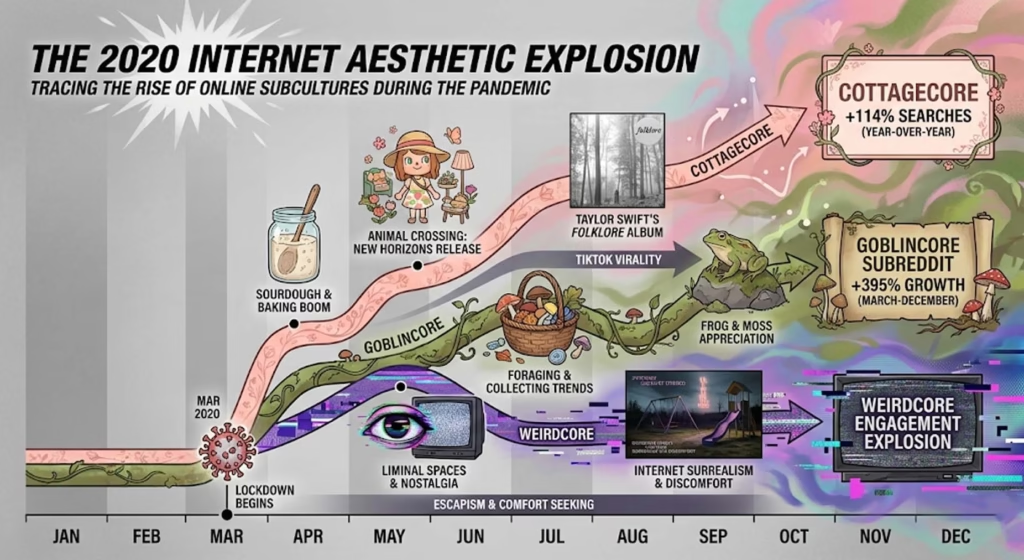

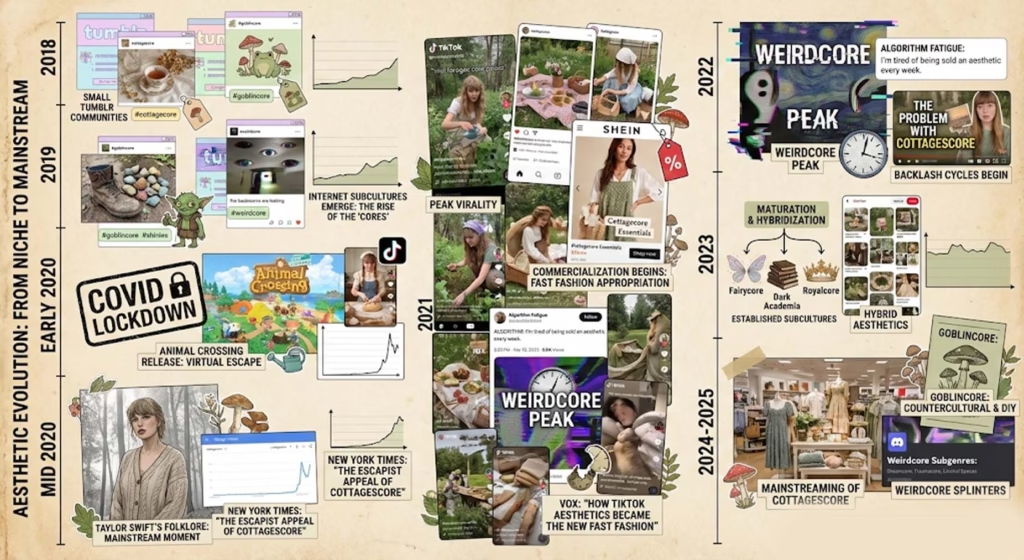

When COVID-19 locked millions indoors in early 2020, internet aesthetics exploded. Google searches for “Cottagecore” increased by over 114% year-over-year. TikTok videos tagged #cottagecore accumulated billions of views. People who’d never baked bread suddenly maintained sourdough starters. Urban apartment dwellers researched backyard chickens and herb gardens.

This wasn’t coincidental. The pandemic stripped away most forms of control—you couldn’t see friends, couldn’t go to work, couldn’t predict the future. But you could control your sourdough starter. You could organize your collection of interesting rocks. You could create surreal digital art processing childhood memories.

Cottagecore offered controlled simplicity—the fantasy that life could be gentle, slow, manageable. Goblincore embraced productive chaos—turning pandemic clutter and isolation into aesthetic virtue. Weirdcore processed the surreal unreality of lockdown life through deliberately surreal imagery. Each aesthetic provided a different coping strategy for the same overwhelming loss of normalcy.

The statistics bear this out. According to a 2024 study in the Journal of Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, participation in aesthetic communities during 2020-2021 correlated with reduced anxiety and improved emotional regulation among Gen Z respondents. These weren’t just pretty pictures—they were genuine therapeutic practices disguised as internet trends.

Gen Z Values and Disillusionment

These aesthetics also reflect deeper generational values and anxieties that preceded the pandemic. Gen Z, coming of age during climate crisis, economic precarity, and political polarization, developed distinct responses to the world they inherited.

The rejection of hustle culture runs through all three aesthetics. Cottagecore explicitly celebrates slowness, domesticity, and opting out of capitalist productivity. Posts feature phrases like “rest is resistance” and “slow living.” Goblincore’s anti-consumerist ethos—”found or built, not bought”—directly challenges consumption as identity. Even Weirdcore, with its nostalgic glitch aesthetics, mourns a pre-optimization internet where creation wasn’t monetized and communities weren’t algorithmic.

Climate anxiety manifests particularly in Cottagecore and Goblincore. Both aesthetics center sustainability, connection to nature, and rejection of the systems destroying the planet. A growing number of Goblincore participants identify as climate activists, combining mushroom foraging with zero-waste lifestyles and ecological education. Cottagecore’s focus on growing food, mending clothes, and handmade goods reflects similar environmental consciousness.

The aesthetics also push back against Instagram’s tyranny of perfection—the “clean girl” aesthetic, minimalist beige, filtered flawlessness. Goblincore celebrates the messy, the chaotic, the aesthetically “wrong.” Weirdcore deliberately employs bad graphics, lo-fi imagery, and amateur aesthetics. There’s a yearning for authenticity, even if that authenticity is itself performed for social media.

Technology and Identity Formation

Perhaps most significantly, these aesthetics demonstrate how digital-native generations construct identity differently than previous cohorts. Gen Z doesn’t see a contradiction between “authentic self” and “online persona”—the digital self IS authentic, just differently expressed.

In physical spaces, you might have one identity: student, employee, child, friend. Online, through platform-hopping and aesthetic-shifting, you can explore multiple facets of selfhood simultaneously. You might be Cottagecore on Instagram (soft, domestic, gentle), Goblincore on TikTok (chaotic, earthy, weird), and Weirdcore on Tumblr (surreal, nostalgic, unsettling)—and all these are genuinely you.

TikTok’s algorithm accelerates this fluid identity play. Based on your watch time and engagement, the For You Page creates increasingly specific subcommunity bubbles. Within hours of engaging with Goblincore content, your entire feed transforms. You’re not choosing an identity and seeking it out—the algorithm discovers your latent interests and surfaces a community you didn’t know existed.

This technological mediation of identity formation explains why aesthetics function as identity frameworks for Gen Z. They’re not adopting a subculture wholesale (like punks or goths of previous generations). They’re sampling, mixing, code-switching between aesthetic languages depending on platform, mood, and social context. The communities provide belonging without demanding exclusivity.

Cottagecore: Romanticizing Rural Simplicity {#cottagecore}

Of the three aesthetics, Cottagecore achieved the most mainstream recognition, influencing fashion runways, interior design trends, and popular music. But beneath the Instagram-ready pastoral imagery lies a complex movement about control, escapism, and gender performance in the digital age.

Visual Language and Core Elements

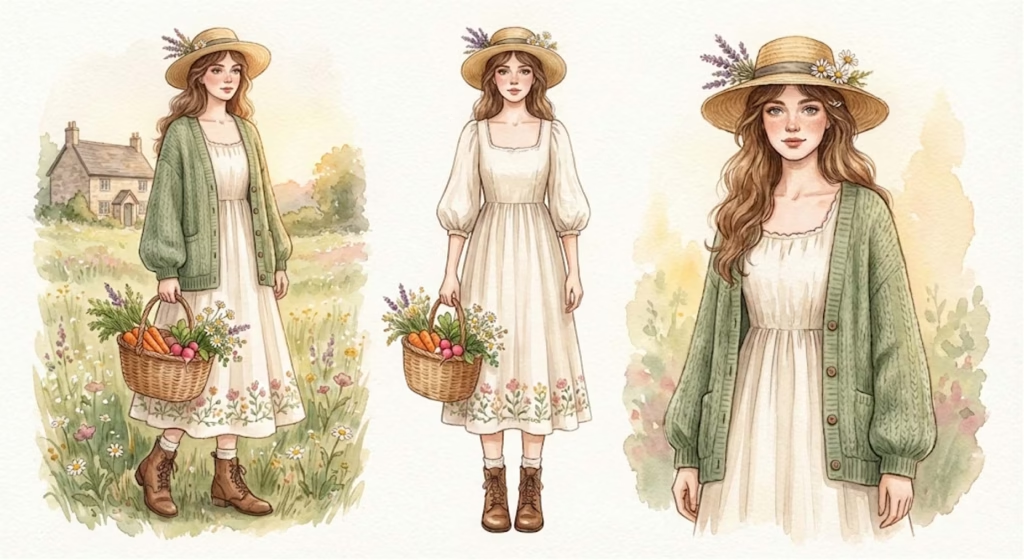

Cottagecore’s aesthetic is instantly recognizable: soft, warm, nostalgic, feminine. The color palette centers on pastels—blush pink, sage green, butter yellow, cream—alongside earthy naturals like terracotta and wheat. Florals dominate, but in vintage, faded patterns rather than bright modern prints. Everything feels slightly aged, gently worn, lovingly used.

Key imagery includes baking (especially bread, pies, jams), gardening (herbs, vegetables, wildflowers), rural landscapes (rolling hills, cottages, meadows), farm animals (chickens, goats, bees), vintage items (mason jars, wicker baskets, floral china), handcrafts (embroidery, knitting, pressed flowers), and natural materials (linen, cotton, wood, stone).

The fashion aesthetic emphasizes natural fibers and vintage-inspired silhouettes: prairie dresses, pinafores, linen trousers, loose blouses, hand-knitted cardigans, vintage floral prints, straw hats, and practical boots. Everything flows, breathes, and suggests ease rather than constraint. The style deliberately evokes pre-1950s rural life, particularly English and Western European countryside aesthetics.

In art and photography, Cottagecore favors watercolor illustrations, pressed flower arrangements, vintage-filter photography (warm tones, soft focus, sun flares), still life compositions, and cozy domestic scenes. The mood is always gentle, warm, inviting—a world where nothing harsh intrudes.

Origins and Evolution

Cottagecore’s roots stretch back further than 2020’s pandemic explosion. Aesthetic historians trace its DNA through multiple movements: the Romanticism of the 18th-19th centuries, Arts & Crafts movement reaction to industrialization, 1970s back-to-the-land communes, and pastoral fantasy literature.

On Tumblr in the early-to-mid 2010s, users began curating images around rural life aesthetics, though the term “Cottagecore” didn’t gain traction until 2018. Early adopters referenced Studio Ghibli films (especially Kiki’s Delivery Service and Howl’s Moving Castle), Jane Austen adaptations, Anne of Green Gables, and The Wind in the Willows. The aesthetic lived quietly in niche corners of the internet, appreciated by a small community.

Then March 2020 happened. Lockdowns created the perfect conditions for Cottagecore to explode. People stuck at home sought visual and imaginative escape. Animal Crossing: New Horizons released at the exact right moment, allowing players to build their cottagecore fantasy islands. Taylor Swift released folklore and evermore, albums steeped in pastoral imagery and cottagecore aesthetics, bringing the movement to mainstream pop culture consciousness.

By summer 2020, major fashion magazines covered the trend. Etsy reported massive increases in searches for prairie dresses, floral patterns, and handmade goods. The aesthetic jumped from niche internet subculture to cultural phenomenon in less than six months.

The Community: Who and Why

Cottagecore’s community skews female-identifying, LGBTQ+ (particularly woman-loving-woman and nonbinary), and spans millennials and Gen Z. The aesthetic holds particular appeal for queer women, offering a domestic fantasy space free from heteronormative expectations.

On Tumblr and TikTok, lesbian and bisexual creators explicitly reclaimed domestic life from patriarchal associations. Baking bread becomes an act of queer joy, not wifely duty. Gardening represents chosen community care, not isolated homemaker labor. The cottage becomes a queer utopia—a place where women love women, tend gardens together, and build lives outside heteronormative structures.

Psychologically, Cottagecore appeals to those craving control, simplicity, and slower living amid capitalist acceleration. There’s deep yearning for pre-industrial rhythms—waking with the sun, growing food, creating useful beautiful things with your hands. The aesthetic offers imagined escape from emails, productivity metrics, and the constant demand to optimize yourself.

The community’s creative practices center on accessible domesticity: baking tutorials dominate TikTok, with creators filming themselves making bread, pies, preserves, and elaborate cakes. Gardening content teaches herb growing, vegetable cultivation, and foraging for wild edibles. DIY crafts include embroidery, pressed flowers, handmade clothing, and natural dyeing. Photography focuses on capturing cozy domestic moments, natural lighting, and seasonal changes.

Cultural Impact and Artistic Influence

Cottagecore’s mainstream success brought both opportunities and tensions. Fashion brands from indie Etsy shops to major labels incorporated prairie dresses, puff sleeves, and floral maximalism. Interior design trends shifted toward maximalist naturalism—dried flowers, rattan furniture, vintage florals, and earthy palettes.

Taylor Swift’s pandemic albums demonstrated Cottagecore’s crossover appeal. The folklore album aesthetic—woods, cabins, vintage sweaters—brought cottagecore to millions who’d never heard the term. Gaming culture embraced it through Animal Crossing, Stardew Valley, and other cozy games celebrating slow living and rural simplicity.

Commercial success created friction with the aesthetic’s anti-capitalist roots. Brands selling $200 “cottagecore” dresses contradicted the movement’s thrifting, mending, and anti-consumerist ethos. Influencers performed cottagecore without understanding its queer roots or political dimensions. The tension between aesthetic and commerce became unavoidable.

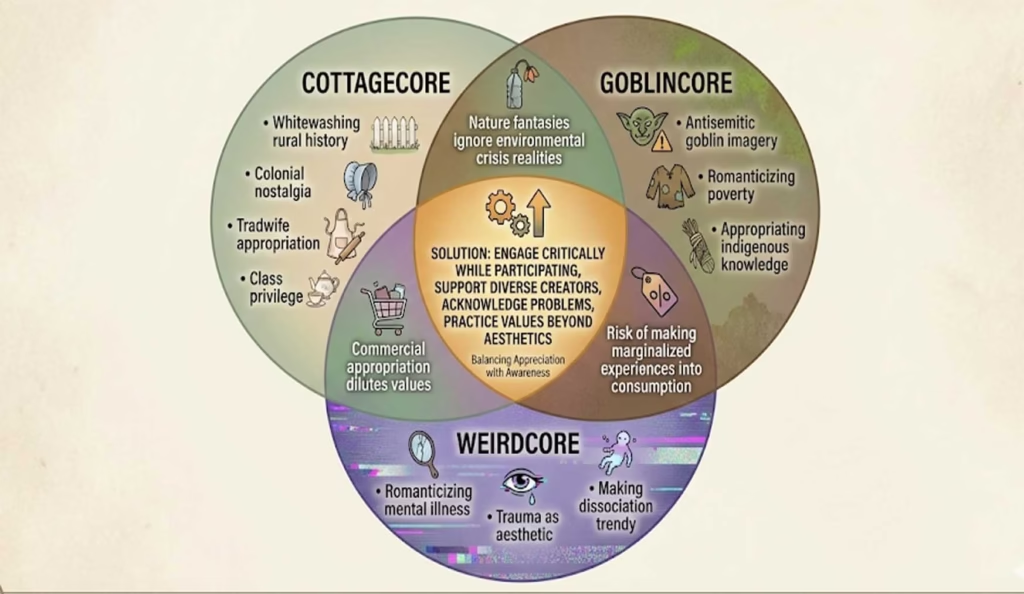

Criticism and Controversy

Cottagecore faces legitimate criticism around several axes. The aesthetic’s overwhelming whiteness and Eurocentric bias romanticizes a rural past that never existed—at least not for most people. The idyllic English countryside imagery erases the colonialism, poverty, and brutal labor that actually characterized rural life. In North American and Australian contexts, cottagecore’s pastoral fantasies often unconsciously celebrate colonial aesthetics built on stolen indigenous land.

The appropriation by the Tradwife movement caused particular concern. Far-right communities adopted cottagecore imagery to promote regressive gender politics, traditional submission, and white ethnonationalism. While most cottagecore participants explicitly reject this association, the visual overlap creates uncomfortable adjacency.

Class privilege marks another criticism. “Cottagecore” lifestyles—moving to rural areas, buying farmland, working from home—require economic resources most people lack. The aesthetic can romanticize poverty while being performable only by the relatively wealthy. Urban people of color, working-class families, and others for whom rural life isn’t an aesthetic choice see their realities gentrified into trendy content.

Despite these issues, many cottagecore creators work to decolonize the aesthetic, highlight diverse rural traditions, acknowledge land histories, and separate escapist fantasy from real-world political positions.

Goblincore: Embracing Nature’s Ugly-Beautiful {#goblincore}

Where Cottagecore seeks pristine pastoral beauty, Goblincore celebrates the chaotic, the overlooked, the conventionally ugly aspects of nature. It’s the aesthetic of mud under your fingernails, mushrooms growing from decay, and finding beauty in what others discard. For many, it feels more honest than Cottagecore’s Instagram-ready gardens—nature as it actually is, not as we wish it were.

Visual Language and Core Elements

Goblincore’s color palette embraces earth in its truest forms: muddy browns, moss greens, deep forest darkness, rusty oranges, earthy yellows, and murky grays. Unlike Cottagecore’s pastels, these colors clash, layer, and refuse to coordinate prettily. The aesthetic celebrates mismatched patterns, worn textures, and the patina of age and use.

Key imagery centers on overlooked nature: mushrooms and fungi of all varieties, frogs, snails, slugs, worms, moss, lichen, bones and skulls, shiny objects (coins, buttons, bottle caps), rocks and crystals, rotting logs, forest floor detritus, and small collected treasures. Where Cottagecore photographs carefully arranged wildflowers, Goblincore documents a slug on a rainy day or the particular way moss grows on a forgotten fence post.

The fashion aesthetic values comfort and practicality above coordination: thrifted, worn, mismatched clothing, layers upon layers, earth-tone everything, big pockets for collecting, sturdy boots (often muddy), oversized sweaters with mysterious stains, and accessories made from found objects. Fashion “rules” don’t apply—if it’s comfortable and has pockets, it’s Goblincore.

Art styles favor found object collages, nature photography (especially macro photography of small creatures), assemblage art using collected items, terrariums and moss jars, hand-drawn field guides, and folk horror aesthetics. The mood ranges from whimsical (cute frog!) to slightly unsettling (why is there a skull in your mushroom jar?).

Origins and Philosophy

Goblincore emerged on Tumblr around 2019, gaining the actual term that spring though similar aesthetics existed earlier. The name references goblin folklore—creatures portrayed as chaotic, greedy for shiny things, dwelling in wild unkempt places, and existing outside civilized society’s rules.

But Goblincore reclaims the goblin from negative connotations. Rather than portraying goblins as evil or frightening, the aesthetic celebrates their rejection of societal norms, their appreciation for unconventional beauty, and their connection to wild spaces. The goblin becomes aspirational—free, untamed, delighted by simple treasures, unconcerned with appearances.

The movement hit full steam during 2020 lockdowns, when people stuck at home sought outdoor activities. Foraging for mushrooms, collecting interesting rocks, and photographing small creatures provided pandemic-safe recreation. TikTok videos of people showing off their “shinies” (collections of small treasures) garnered millions of views. By July 2021, the Goblincore subreddit had grown 395% year-over-year, and Etsy searches for Goblincore items increased 695%.

Central to Goblincore philosophy is explicit anti-consumerism. The motto “found or built, not bought” pervades the community. Rather than purchasing aesthetic items, Goblincore practitioners collect, forage, thrift, and create. Your mushroom identification guide came from the library. Your terrarium uses a jar from recycling and moss from the backyard. Your clothing came from thrift stores. This positions Goblincore against Instagram consumer aesthetics where buying the right products creates the look.

The Community: Chaos and Belonging

Goblincore attracts a notably different demographic than Cottagecore. The community skews younger (Gen Z rather than millennial), heavily neurodivergent (especially ADHD and autistic individuals), and queer (particularly nonbinary and transmasculine people).

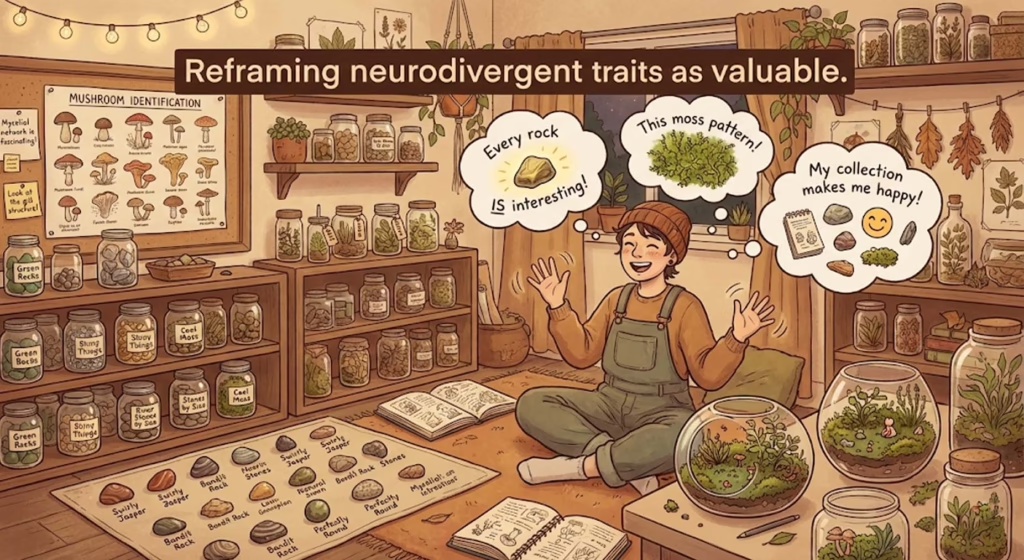

The connection to neurodivergence runs deep. Goblincore celebrates collecting and hoarding—behaviors often pathologized when associated with ADHD or autism. Having seventeen rocks because each one is interesting? That’s not weird; it’s Goblincore. Fixating on mushroom identification to the exclusion of other concerns? That’s not hyperfixation; it’s expertise. The aesthetic reframes neurodivergent traits as valid, valuable, and even aspirational.

The catchphrase “no gender, only bugs” captures Goblincore’s appeal to nonbinary communities. The aesthetic explicitly rejects gendered expectations—no dresses required, no makeup necessary, no performance of traditional femininity or masculinity. You can be muddy, chaotic, interested in worms, and completely unbothered by how others perceive your gender presentation. It’s liberating for those who never felt comfortable in the binary.

Psychologically, Goblincore offers a different kind of comfort than Cottagecore. Rather than seeking control through curation and aestheticization, it finds peace in accepting chaos, mess, and imperfection. Your room is cluttered with interesting rocks? That’s not a problem to fix; that’s your collection. You’re fascinated by decomposition and decay? That’s not morbid; that’s understanding nature’s cycles.

As one community member described it: “Goblincore is Cottagecore for people who actually spend time in nature, who know that nature is not sunshine and pretty flowers—it’s mud and bugs and things rotting and that’s beautiful too.”

Creative Practices and Art-Making

Goblincore’s artistic practices center on accessible engagement with nature and found objects. No expensive art supplies needed—just observation, collection, and creativity.

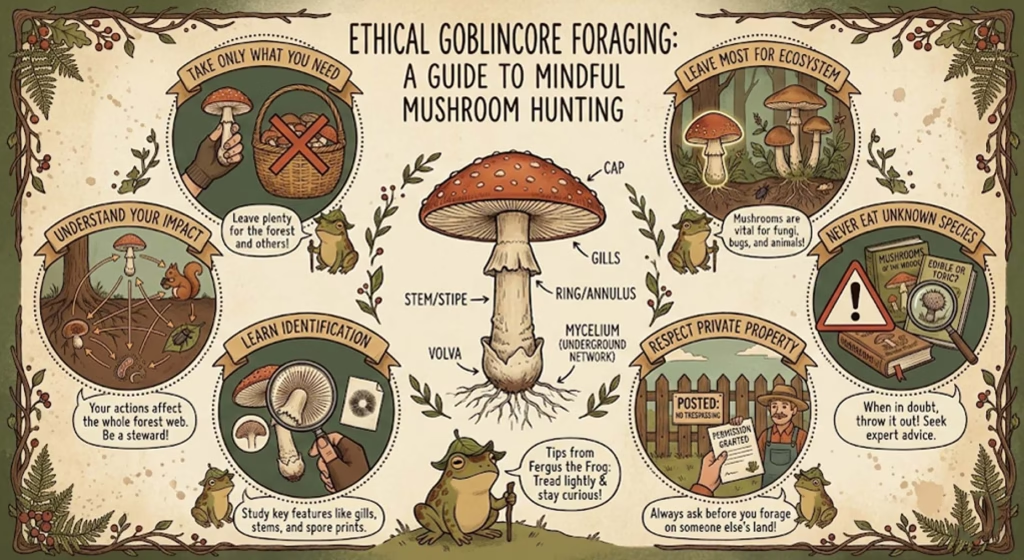

Foraging forms the foundation, though with important ethical considerations. Community guides emphasize sustainable foraging (take only what you need, leave most for ecosystem), species identification (never consume unknown mushrooms), permission and legality (respect private property and protected areas), and ecosystem awareness (understand your impact). Foraging isn’t just gathering—it’s developing relationships with local ecosystems.

Photography practices focus on macro and nature photography: documenting mushrooms and fungi, photographing small creatures (frogs, snails, insects), capturing forest floor details, and celebrating “ugly” nature moments. Equipment ranges from professional cameras to smartphones—the important part is the eye for overlooked beauty.

Collecting “shinies” becomes both practice and identity. Goblincore practitioners curate collections of shiny objects (coins, bottle caps, jewelry, glass), interesting rocks and crystals, bones and shells (ethically sourced), buttons and trinkets, and natural treasures (pinecones, acorns, seed pods). The collections themselves become art—assemblages in jars, organized displays, curiosity cabinets of personal meaning.

Found object art and assemblage turn collections into creation: terrariums using recycled containers, moss jars and tiny ecosystems, collages incorporating natural items, painted rocks and bones, and shadow boxes arranging treasures into compositions.

Cultural Significance

Beyond aesthetics, Goblincore represents important cultural work around acceptance and environmental connection. The movement normalizes neurodivergent ways of being, celebrates gender nonconformity, builds genuine ecological knowledge, and practices anti-consumerist values in tangible ways.

The community has become unexpectedly effective at environmental education. Through sharing mushroom identification, ecosystem knowledge, and foraging ethics, Goblincore creators teach ecology more engagingly than many formal programs. Young people who might never pick up a mycology textbook happily learn from TikTok mushroom content because it’s framed as aesthetic participation rather than academic study.

The connection to climate activism also runs deep. Many Goblincore participants engage in zero-waste lifestyles, habitat restoration, and local environmentalism. The aesthetic’s grounding in actual nature—not idealized rurality—creates awareness of environmental degradation and ecosystem fragility. You can’t forage mushrooms in a clearcut forest.

Concerns and Criticisms

Goblincore isn’t without problems. The most serious concern involves antisemitism in goblin imagery. Historical European folklore frequently portrayed Jews as goblins—a harmful stereotype persisting through modern media. While most Goblincore participants don’t intend antisemitism, the unconscious perpetuation of these tropes causes real harm.

Community discussions emphasize careful handling of goblin imagery: avoid depictions of goblins as greedy or obsessed with gold/money (antisemitic tropes), don’t perpetuate hook-nosed or other caricatured features, focus on nature appreciation rather than goblin characters, and educate yourself about historical antisemitism in folklore. Many practitioners prefer emphasizing the “core” (nature appreciation, collecting) over literal “goblin” associations.

Other criticisms include romanticizing poverty (celebrating thrifting and worn clothes when these aren’t choices for everyone), potential for appropriating indigenous foraging knowledge without credit, and surface-level participation that doesn’t engage with anti-consumerist values beyond aesthetics.

Despite these concerns, Goblincore represents a genuine alternative to consumption-driven online culture. When practiced thoughtfully, it offers paths toward environmental connection, neurodivergent acceptance, and finding beauty beyond conventional standards.

Weirdcore and Dreamcore: Digital Surrealism and Liminal Unease {#weirdcore}

If Cottagecore and Goblincore ground themselves in physical nature, Weirdcore exists purely in the digital realm. This is the aesthetic of glitched childhood memories, liminal spaces, and the particular nostalgia of growing up online. It processes internet-age anxiety through deliberately unsettling surrealism.

Visual Language and Core Elements

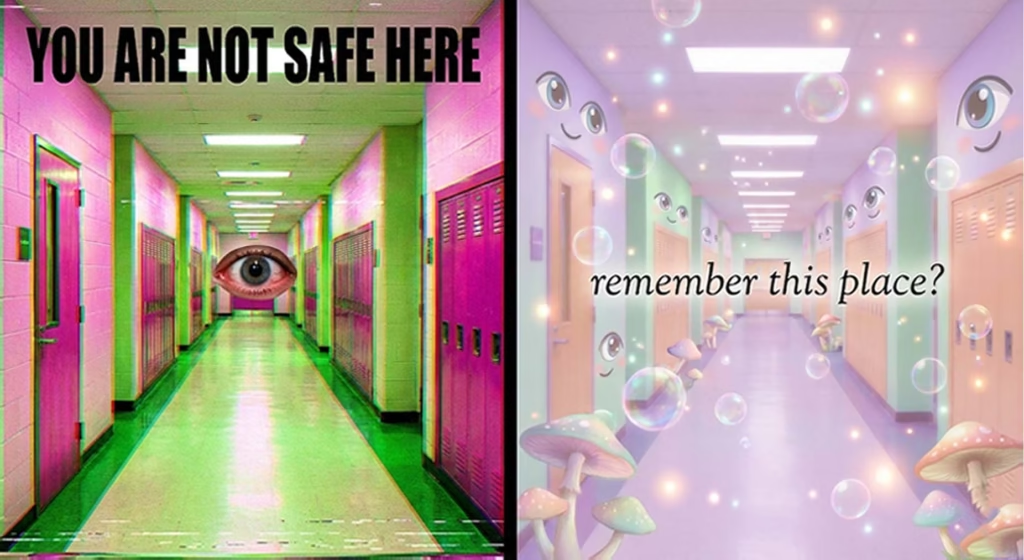

Weirdcore and Dreamcore, while related, pursue different emotional goals through similar visual languages. Weirdcore aims for confusion, unease, and alienation. Dreamcore seeks comfort, wonder, and nostalgic familiarity. Both employ surreal, digitally manipulated imagery, but to opposite emotional ends.

Weirdcore’s visual markers include distorted low-resolution imagery, VHS glitches and analog degradation, oversized eyes (often poorly edited onto scenes), cryptic text messages (“you are not safe here,” “wake up”), bright unnatural color palettes, crude amateur editing aesthetics, and liminal spaces—empty playgrounds, fluorescent-lit hallways, abandoned malls.

Dreamcore shares similar techniques but shifts the mood: hazy bright lighting, pastel and saturated colors, softer surreal elements (mushrooms with eyes, floating objects), 3D-rendered landscapes, and cryptic but less threatening text. Where Weirdcore unsettles, Dreamcore soothes with the same visual language.

Key imagery for both includes early internet aesthetics (Windows XP desktops, old computer graphics, pixelated textures), childhood locations (empty playgrounds, school hallways, liminal recreational spaces), distorted faces and body parts (especially eyes), impossible architecture, and nostalgic technology references.

The color palettes diverge notably: Weirdcore favors harsh contrasts, oversaturation, and jarring combinations—electric pink against sickly green. Dreamcore prefers soft pastels, gentle gradients, and bright but harmonious colors. Both avoid naturalism, but Dreamcore’s unnaturalness feels whimsical where Weirdcore’s feels wrong.

Origins and Platform Culture

Weirdcore’s origins trace to Tumblr around 2018, when user Gabriel Traversat began posting surreal, low-res 3D landscapes. The aesthetic drew from earlier internet movements—Vaporwave’s nostalgic digitalism, Liminal Space photography, analog horror, and Y2K aesthetic revival. But where Vaporwave critiqued capitalism through 80s mall aesthetics, Weirdcore processed childhood memory and internet-age dissociation.

TikTok exploded Weirdcore into mainstream visibility during 2020-2022. The platform’s short video format proved perfect for creating unsettling mood pieces—thirty seconds of distorted imagery, slowed music, and cryptic text could evoke powerful emotional responses. Creators like @weirdcore_world accumulated millions of followers by posting daily surreal content.

The aesthetic’s relationship to analog horror became symbiotic. Series like The Backrooms, Local 58, and work by creators like Kane Pixels employed similar visual languages. Weirdcore provided the aesthetic toolkit; analog horror built narrative around it. Both processed digital-age anxieties through deliberately degraded, pre-digital visual aesthetics.

Music became inseparable from the visual aesthetic. Artists like Jack Stauber, whose songs blend nostalgic children’s music with unsettling manipulation, became Weirdcore anthems. Slowed and reverbed versions of childhood songs created the sonic equivalent of the visual corruption—familiar made strange.

Psychology: Nostalgia, Dissociation, and Digital Age Anxiety

The psychological appeal of Weirdcore and Dreamcore centers on processing complex emotions around childhood, memory, and internet-mediated reality. The aesthetics tap into anemoia—nostalgia for times you didn’t experience or can’t fully remember. The grainy playground video isn’t your specific childhood, but it evokes the feeling of childhood memory—hazy, incomplete, emotionally charged.

For internet-native Gen Z, childhood memories are inherently digital. Windows XP loading screens, early video game graphics, liminal online spaces—these aren’t just nostalgia objects; they’re genuine memory anchors. Weirdcore’s use of early internet aesthetics isn’t ironic. It’s how this generation actually remembers growing up.

The aesthetics also process dissociation and derealization—psychological experiences where reality feels unreal, distant, or dreamlike. Many young people experience these states, sometimes related to trauma, anxiety, or neurodivergence. Weirdcore’s deliberately disorienting imagery externalize these internal experiences. Creating or viewing this content becomes a way to say: “This is how I experience the world sometimes.”

The comfort in controlled unease matters here. Real-world chaos feels threatening and unmanageable. But Weirdcore’s unsettling imagery is contained, chosen, and created. You can close the app. You can make the art yourself. The controlled discomfort paradoxically soothes deeper anxieties.

Dreamcore offers an alternative approach to similar emotions—finding comfort rather than confronting unease. Both aesthetics acknowledge that reality feels strange, memory feels corrupted, and growing up online created unique psychological experiences. They just offer different coping strategies.

The Weirdcore Eye: Symbolism and Meaning

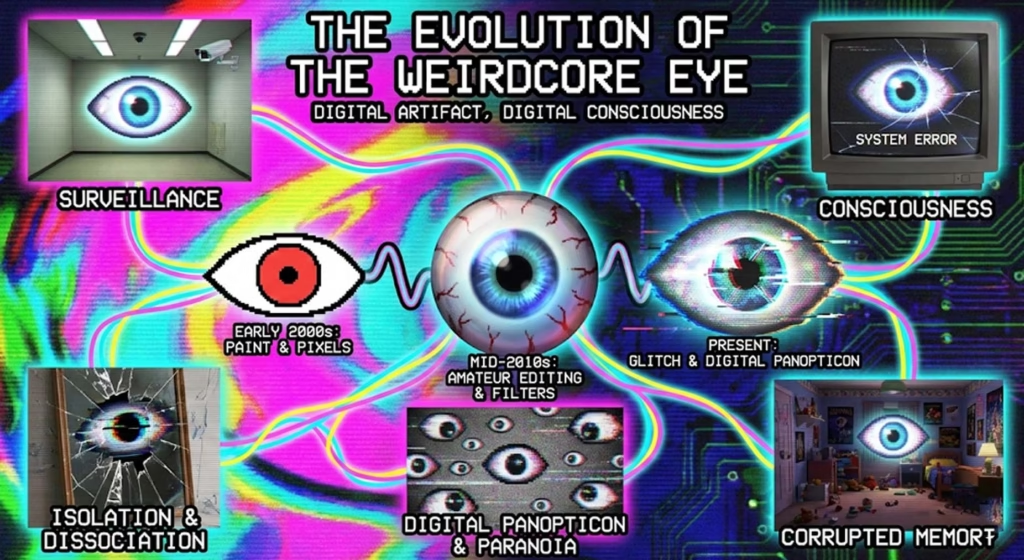

The single oversized eye—Weirdcore’s most recognizable symbol—deserves particular attention. Eyes appear constantly: poorly Photoshopped onto landscapes, floating in empty rooms, watching from impossible angles, gazing directly at viewers.

Human psychology hardwires us to respond to eyes. From infancy, we track gaze direction to understand intention and social cues. Eyes signal consciousness, awareness, observation. In horror, eyes represent being watched—surveillance, paranoia, exposure.

Weirdcore’s eye serves multiple symbolic functions. It’s surveillance—the constant observation of digital life, algorithms tracking every click, the panopticon of social media. It’s loneliness—a single eye in empty space, isolated awareness without connection. It’s consciousness—the observer position we occupy in dissociative states, watching ourselves from outside. And it’s mystery—the unblinking eye offers no explanation, just perpetual observation.

The eye’s crude editing matters too. These aren’t professionally manipulated images—they’re amateur, deliberately bad Photoshops. This DIY quality democratizes the symbol. Anyone can add an eye to an image. The barrier to entry is zero. The crude aesthetic itself signals: this isn’t professional art trying to impress you; this is someone processing emotions through whatever tools they have.

Creative Techniques and Art-Making

Creating Weirdcore and Dreamcore art requires minimal technical skill but strong aesthetic vision. The amateur quality is feature, not bug.

Digital tools range from professional to completely free. Photo manipulation happens in Photoshop, GIMP, or mobile apps like PicsArt and Picsart. The key is layering: combining stock photos, childhood images, eyes, text, and distortion effects. Glitch effects come from deliberately corrupting images, applying VHS filters, or using datamoshing techniques. Text overlays use generic fonts (Impact, Arial, Comic Sans) with crude placement.

3D rendering creates many Dreamcore landscapes. Programs like Blender allow creation of impossible architecture, surreal spaces, and nostalgic-yet-wrong environments. The amateur 3D aesthetic—poorly textured, weirdly lit, uncanny valley characters—perfectly suits the mood.

Audio manipulation amplifies the visual. Taking familiar songs and applying: slowed tempo (often 800% slower), excessive reverb creating cavernous space, pitch shifting into uncanny ranges, and distortion degrading audio quality. These techniques transform childhood songs into unsettling soundscapes.

Video editing combines all elements. Thirty-second TikToks layer distorted imagery, cryptic text, slowed music, and simple transitions. The format limits complexity, which paradoxically strengthens impact—one powerful image with three words of text can evoke more than elaborate production.

Community and Cultural Impact

Weirdcore’s community skews very young Gen Z—teenagers who grew up entirely online, for whom digital and physical reality blur seamlessly. The aesthetic appeals particularly to those experiencing dissociation, derealization, or simply the alienation of internet-mediated life.

The movement influenced broader digital culture significantly. Analog horror as a genre owes massive debt to Weirdcore aesthetics. Creators like Kane Pixels (The Backrooms) use identical visual languages: liminal spaces, low-res imagery, unsettling emptiness. The crossover audience is substantial.

Video games influenced by and influencing the aesthetic include LSD Dream Emulator, Yume Nikki, and OMORI—games exploring surreal dreamscapes, corrupted memory, and psychological horror through similar visual aesthetics. The two-way influence creates feedback loops: games inspire aesthetics, aesthetics inspire game creators.

Music visualizers and concert visuals increasingly incorporate Weirdcore elements. The aesthetic’s combination of nostalgia and unease resonates with certain alternative music scenes. Artists exploring internet-age melancholy find visual expression through these aesthetic languages.

Dreamcore vs. Weirdcore: Key Distinctions

While often conflated, Dreamcore and Weirdcore pursue different emotional goals:

Weirdcore seeks:

- Confusion and disorientation

- Dread and unease

- Alienation and isolation

- Confronting psychological distress

- “Something is wrong here”

Dreamcore seeks:

- Wonder and curiosity

- Comfort and familiarity

- Nostalgia and anemoia

- Soothing through surrealism

- “This feels like home somehow”

Visual differences include:

- Weirdcore: Harsh lighting, threatening text, empty spaces

- Dreamcore: Soft lighting, whimsical elements (mushrooms with eyes), populated spaces with strange characters

- Weirdcore: Distortion for unease

- Dreamcore: Distortion for whimsy

The communities overlap significantly—many creators work in both modes depending on mood and message. But the emotional intentions differ fundamentally.

Criticism and Debate

Weirdcore faces several criticisms, primarily around potentially romanticizing mental illness. The aesthetic’s heavy use of dissociation, derealization, and trauma imagery concerns mental health advocates. Does creating/consuming this content help people process difficult experiences, or does it glamorize psychological distress?

The relationship to Traumacore (a related aesthetic explicitly about processing trauma) complicates this. Some find creating surreal art genuinely therapeutic—externalizing internal experiences helps manage them. Others worry young people might adopt dissociative aesthetics without understanding the serious mental health issues they reference.

Cringe culture backlash also targets Weirdcore, particularly on TikTok. Ironic communities mock the aesthetic as pretentious, try-hard surrealism for people who don’t understand “real” surrealism. The amateur quality invites dismissal from those who value technical skill over emotional resonance.

Generational divide further complicates reception. For those who didn’t grow up online, Weirdcore seems random, meaningless, or performatively weird. The emotional resonance depends on shared experience of internet-mediated childhood. Without that context, it’s just bad Photoshop and cryptic text.

Despite criticisms, Weirdcore represents genuine artistic innovation—using digital tools and internet platforms to create new visual languages for processing distinctly 21st-century psychological experiences. Whether it’s “good art” by traditional standards matters less than its evident power to move, disturb, comfort, and connect its community.

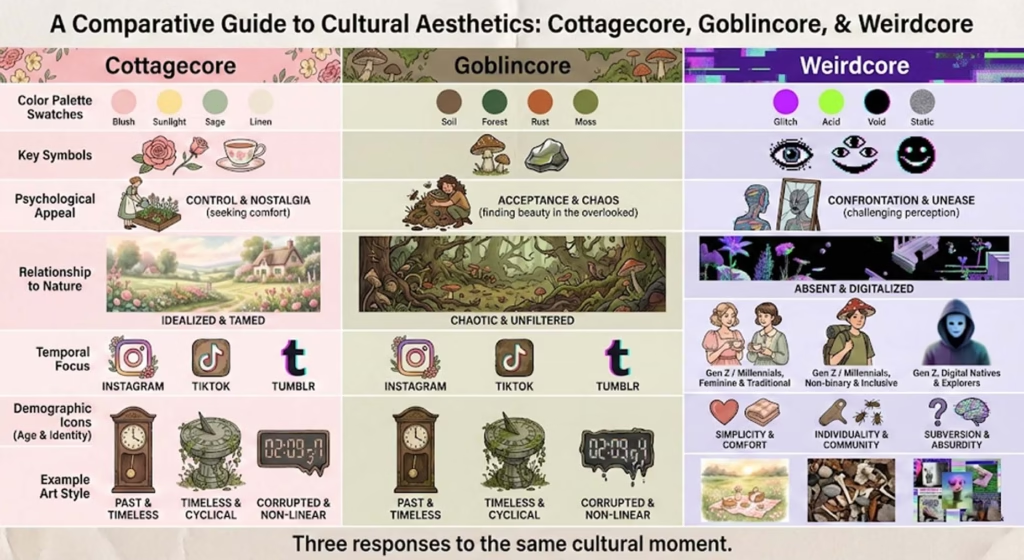

Comparative Analysis: Three Paths to Escape

Understanding how Cottagecore, Goblincore, and Weirdcore differ reveals the diverse psychological needs they serve and the various ways people seek meaning, beauty, and belonging in digital spaces.

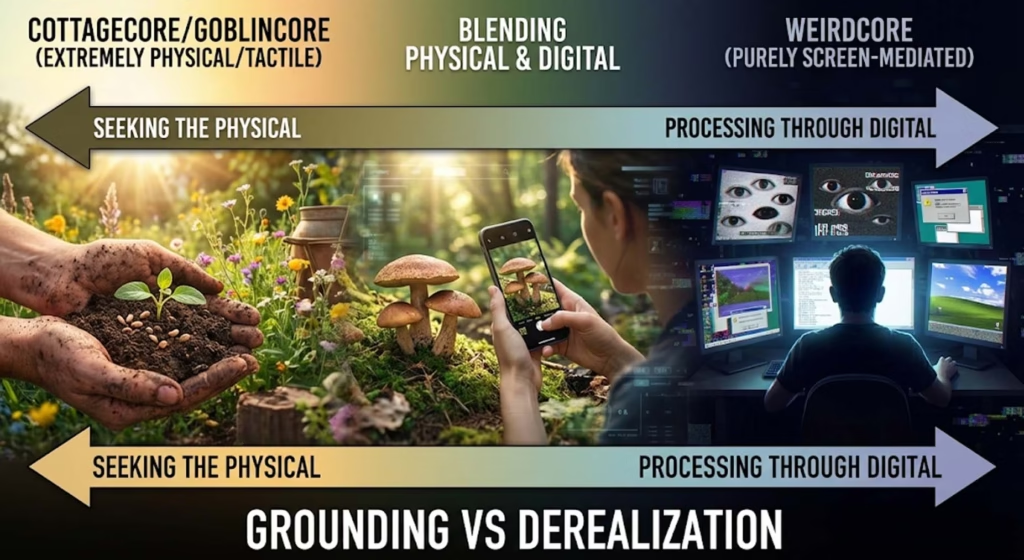

Nature vs. Digital: Grounding vs. Derealization

The fundamental split between these aesthetics lies in their relationship to physical reality. Cottagecore and Goblincore root themselves firmly in the material world—gardens you can tend, bread you can bake, mushrooms you can actually touch. They promise tactile engagement, sensory grounding, and embodied experience as antidotes to digital overload.

Weirdcore exists entirely in the digital realm. Its landscapes aren’t real places. Its eyes aren’t actual objects. The whole aesthetic is screen-mediated, existing only through digital manipulation. Rather than offering escape from digital life, it processes digital life through its own language.

This reveals two opposite coping strategies for the same problem. Some people respond to internet saturation by seeking the physical world—going outside, growing things, collecting actual objects. Others lean into the digital, finding expression through the very medium causing distress. Neither is better; they address different needs.

Order vs. Chaos: Control vs. Acceptance

Cottagecore seeks control through curation and aestheticization. The carefully arranged bread on the rustic cutting board, the precisely composed bouquet, the coordinated vintage outfit—all demonstrate mastery over environment and presentation. In chaotic times, Cottagecore offers the fantasy: “I can make things beautiful, ordered, manageable.”

Goblincore embraces chaos and finds beauty within it. The mismatched outfit, the cluttered collection of rocks, the appreciation for decay—all accept that life is messy and that’s okay. The coping strategy isn’t control but acceptance: “Things are chaotic and weird and that can be beautiful too.”

Weirdcore occupies a middle space—creating controlled unease. The surreal imagery is chaotic, but it’s deliberately chosen and created chaos. You manufacture the discomfort, which gives you power over it. It’s not acceptance or control but rather: “I’ll make something that feels as strange as life feels, and in creating it, I’ll understand it better.”

Past vs. Future: Temporal Orientations

Each aesthetic orients differently toward time, revealing what anxieties they address.

Cottagecore looks to an idealized past—specifically pre-industrial rural life. It’s fundamentally nostalgic, yearning for simpler times that probably never existed. This temporal orientation makes sense for those feeling overwhelmed by accelerating technological change, who wish we could return to slower rhythms.

Goblincore exists in timeless present—natural cycles operate on deep time. Mushrooms don’t care about productivity schedules. Ecosystems function whether humans notice or not. This grounds participants in cyclical time rather than linear progress. There’s comfort in connecting with processes older and slower than human concerns.

Weirdcore manipulates corrupted past—specifically childhood memories viewed through digital degradation. It’s nostalgic but for the very recent past, and that nostalgia is deliberately distorted, corrupted, made strange. This reflects internet-age experience where “the past” is five years ago and memory itself feels digital, editable, unstable.

Community Demographics and Values

While overlaps exist, each aesthetic attracts somewhat different communities:

Cottagecore:

- Millennials and older Gen Z

- Women (cis and trans), nonbinary people

- LGBTQ+ (especially WLW)

- Values: Sustainability, slow living, domestic reclamation, gentle escapism

Goblincore:

- Younger Gen Z

- Heavy neurodivergent representation

- Nonbinary and transmasculine focus

- Values: Anti-consumerism, neurodivergent acceptance, ecological connection, chaotic authenticity

Weirdcore/Dreamcore:

- Very young Gen Z, internet-native

- Those experiencing dissociation/derealization

- Gamers and digital artists

- Values: Emotional processing, surreal expression, nostalgia for digital childhood

The demographic splits reveal how different life experiences create different aesthetic needs. Older millennials might relate to Cottagecore’s longing for pre-digital simplicity. Neurodivergent Gen Z connects with Goblincore’s acceptance of “weird” collecting behaviors. Internet-native teens process digital-age psychology through Weirdcore.

Comprehensive Comparison Table

| Element | Cottagecore | Goblincore | Weirdcore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color Palette | Soft pastels, warm earth tones | Muddy browns, moss greens, earthy | Harsh neons, oversaturated, glitchy |

| Key Symbols | Flowers, bread, cottages, gardens | Mushrooms, frogs, bones, shiny objects | Eyes, liminal spaces, distorted childhood |

| Psychological Appeal | Control through curation | Acceptance of chaos | Confronting/creating unease |

| Relationship to Nature | Idealized/romanticized | Authentic/chaotic | Absent/digital |

| Temporal Focus | Idealized past | Timeless present | Corrupted recent past |

| Primary Platform | Instagram, Pinterest, TikTok | TikTok, Tumblr, Reddit | TikTok, Tumblr |

| Demographics | Millennial/older Gen Z, WLW | Younger Gen Z, neurodivergent, nonbinary | Internet-native Gen Z |

| Core Values | Sustainability, slow living | Anti-consumerism, acceptance | Emotional processing, surrealism |

| Art Practices | Baking, gardening, photography | Foraging, collecting, nature photography | Digital manipulation, glitch art |

| Historical Influences | Romanticism, Arts & Crafts | Folk art, found object art | Surrealism, Vaporwave, analog horror |

This table demonstrates that while all three emerged from similar cultural conditions (pandemic, digital saturation, Gen Z values), they offer remarkably different responses to those conditions.

Artistic Practices: How These Communities Create

These aren’t passive consumer communities—they’re active art-making movements with specific tools, techniques, and creative practices. Understanding how people actually create within these aesthetics reveals their depth beyond surface visuals.

Digital Art Tools and Techniques

While Cottagecore and Goblincore incorporate physical practices, all three aesthetics rely heavily on digital tools for creation and sharing.

Photo editing forms the foundation. Mobile apps like VSCO, Lightroom Mobile, Snapseed, and PicsArt allow accessible editing with preset filters (Cottagecore warm tones, Weirdcore glitch effects) and adjustment tools (Goblincore earthy saturation). Desktop software includes Photoshop for advanced manipulation, GIMP as free alternative, and Affinity Photo for middle-ground option.

Digital illustration expands creative possibilities. Procreate on iPad dominates for painting and drawing, perfect for Cottagecore watercolor aesthetics and Dreamcore surreal illustrations. Clip Studio Paint serves comic and illustration work. Adobe Fresco bridges traditional and digital art. Even free tools like Krita or Medibang enable quality digital art creation.

For Weirdcore specifically, 3D rendering becomes essential. Blender, free and powerful, creates the impossible architectures and surreal landscapes. Dreams on PlayStation provides accessible 3D creation. Even simpler tools like Voxel editors create the retro 3D aesthetic.

Video editing, crucial for TikTok content, ranges from mobile apps (CapCut, InShot, VN) to desktop software (Adobe Premiere, DaVinci Resolve). The short-form video format rewards simple, impactful edits over complex effects.

AI art tools have recently entered the aesthetic toolkit. Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion can generate aesthetic-specific imagery through careful prompting. This remains controversial—some view AI as democratizing art creation; others see it as antithetical to authentic creative practice.

Physical Art Practices

Cottagecore and Goblincore particularly emphasize tangible, hands-on creation beyond the digital.

Cottagecore physical practices include:

- Pressed flower art and preservation

- Watercolor painting of natural subjects

- Embroidery and cross-stitch (often with floral or pastoral motifs)

- Film photography or vintage-style digital photography

- Botanical illustration and nature journaling

- Baking as creative practice (decorating, styling, photographing)

- Natural dyeing of fabrics

- Gardening as artistic expression

Goblincore physical practices feature:

- Foraging (mushrooms, interesting plants, natural objects)

- Nature photography, especially macro

- Found object assemblage and collage

- Creating terrariums and moss ecosystems

- Painting rocks, bones, and found objects

- Building curiosity cabinets and display collections

- Field guides and nature journaling with personal aesthetic

- Thrift store upcycling and customization

The physicality matters. In increasingly screen-mediated lives, these practices offer tactile, embodied engagement. Making something with your hands, going outside to forage, arranging physical objects—these counter the endless scroll of digital consumption.

Platform-Specific Creation

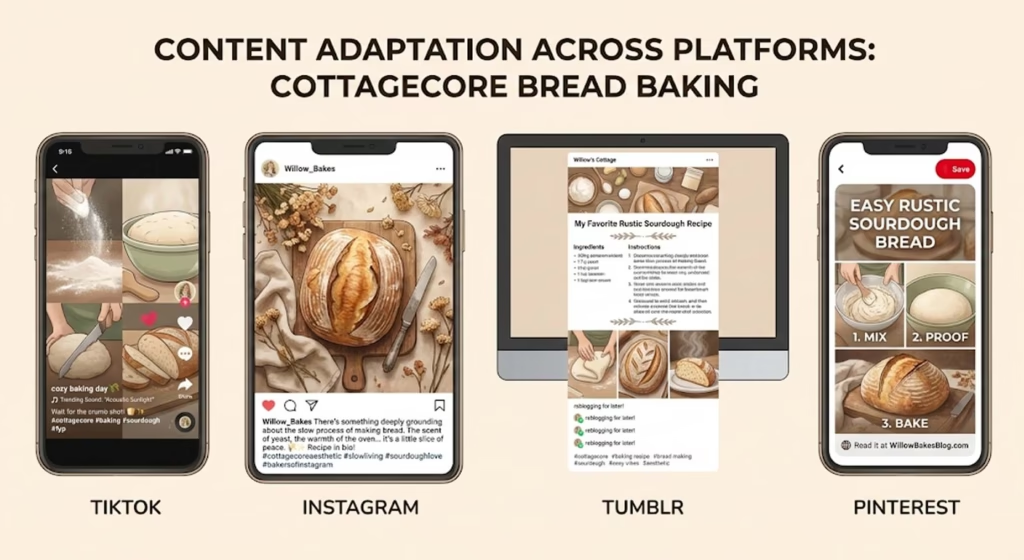

Each platform shapes how aesthetics manifest creatively.

TikTok demands:

- Short-form video (15-60 seconds typically)

- Trend participation (sounds, formats, challenges)

- Fast cuts and visual variety

- Text overlay for accessibility

- Vertical format optimization

- Immediate visual hook (first 3 seconds crucial)

Instagram rewards:

- Grid cohesion and aesthetic consistency

- High-resolution photography

- Carousel posts telling visual stories

- Reels for movement and sound

- Carefully curated caption narrative

- Strategic hashtag use

Tumblr allows:

- Long-form text and context

- Multi-image posts and gif sets

- Reblog chains building conversations

- Tags creating discovery paths

- Mixed media (text, images, quotes, links)

- Anonymity enabling different expression

Pinterest functions as:

- Visual bookmarking and moodboarding

- Discovery through related pins

- Link-driving to blogs and shops

- Seasonal and trend forecasting

- Tutorial and how-to hub

Understanding platform constraints and affordances shapes how communities create and share. A Cottagecore TikTok might show bread-making in hyperlapse. The same content on Instagram becomes a carousel of styled process photos. On Tumblr, it includes a recipe, reflections on slow living, and links to flour sources.

Collaborative and Participatory Art

Internet aesthetic communities practice remarkably collaborative creation, blurring lines between original creator and audience.

TikTok’s duet and stitch features enable direct collaboration. Someone posts mushroom foraging content; dozens duet with their own foraging adventures. Someone creates Weirdcore imagery; others stitch reactions or add their own layers. The original post becomes collaborative starting point rather than finished product.

Art challenges and prompts drive community creation. Weekly themes (“show your goblincore collection,” “cottagecore in your city,” “create weirdcore based on childhood fear”) generate hundreds of interpretations. The challenge format builds community while teaching techniques.

Crowdsourced aesthetics mean communities themselves define visual languages. No single authority dictates what counts as “true” Goblincore. Through millions of posts, tags, and community discussions, collective understanding emerges. New members learn by observing, creating, and receiving community feedback.

Fan art and reinterpretation culture thrives. Popular creators become subjects of others’ art. Aesthetic crossovers emerge (Goblincore Weirdcore hybrids). Memes remix aesthetic elements into new meanings. The community constantly creates, responds, reinterprets, and evolves.

Cultural Impact Beyond the Internet

While born online, these aesthetics have influenced mainstream culture, commercial design, and artistic movements far beyond their digital origins.

Fashion and Design Industry Influence

Fashion industry adoption happened rapidly, with varying degrees of thoughtfulness. Cottagecore particularly penetrated mainstream fashion.

Runway incorporation appeared from designers like Simone Rocha (romantic ruffles, pastoral references), Batsheva (prairie dresses, vintage-inspired designs), and Sandy Liang (cute, cozy, deliberately sweet aesthetics). These designers translated internet aesthetics into high fashion while maintaining creative integrity.

Fast fashion predictably appropriated without understanding. Mass market brands released “cottagecore collections” of cheap floral dresses, missing the aesthetic’s anti-consumerist roots entirely. The irony of buying Shein cottagecore to perform anti-capitalism escaped many participants.

Interior design trends shifted noticeably. Maximalist cottagecore replaced minimalist Scandinavian as aspirational aesthetic. Design blogs featured dried flowers, vintage florals, rattan furniture, and abundant plants. Even mainstream retailers like Target marketed “cottagecore” and “grandmillennial” collections.

Goblincore’s influence appeared in “cluttercore” and acceptance of maximalist, eclectic interiors. The Kondo-era minimalism gave way to visible collections, curated chaos, and personality-filled spaces. Terrarium sales boomed. Mushroom decor became ubiquitous.

Weirdcore influenced graphic design and UX/UI. Deliberate glitch aesthetics, retro computer graphics, and liminal space photography appeared in brand campaigns for companies targeting Gen Z. The amateur aesthetic became professional design choice.

Music and Entertainment

Musicians both shaped and responded to aesthetic movements. Taylor Swift’s folklore and evermore albums brought Cottagecore to pop mainstream, their aesthetics of cabins, woods, and vintage sweaters reaching millions. Alternative artists like Ethel Cain, Faye Webster, and Phoebe Bridgers embodied various aesthetic values—melancholic slowness, pastoral imagery, emotional vulnerability.

For Weirdcore, Jack Stauber became near-synonymous with the aesthetic. His songs blending nostalgic children’s music with unsettling manipulation provided perfect soundtracks. Artists like 100 gecs and Frost Children incorporated glitchy, chaotic elements aligned with digital aesthetics.

Video games both influenced and reflected these movements. Animal Crossing: New Horizons released perfectly timed for Cottagecore’s pandemic boom, allowing players to build cottage fantasy islands. Stardew Valley offered cozy farming simulation aligned with slow living values. Horror games like OMORI and Inscryption employed Weirdcore aesthetics for unsettling effect.

Film and television incorporated aesthetic elements more slowly. A24 films like The Lighthouse, Midsommar, and The Green Knight employed folk horror and pastoral surrealism resonating with aesthetic communities. Streaming shows began featuring characters explicitly into these aesthetics, though often superficially.

Fine Art and Gallery World

Contemporary artists working in or influenced by these aesthetics began receiving gallery recognition. The internet-to-gallery pipeline accelerated, with artists discovered on Instagram or TikTok exhibiting in physical spaces.

Glitch artists, liminal space photographers, and digital surrealists found audiences in contemporary art galleries. The distinction between “internet art” and “fine art” continued blurring. Museums began collecting internet-born art, recognizing its cultural significance.

Academic discourse expanded around internet aesthetics. Art history and digital culture scholars analyzed these movements as genuine artistic innovations. Conferences featured panels on TikTok aesthetics. University courses examined internet visual culture seriously rather than dismissively.

The validation by art institutions created tension. Some community members saw gallery recognition as success; others viewed it as co-option, removing aesthetics from their democratic, accessible origins and recontextualizing them in elite spaces.

Economic and Commercial Dimensions

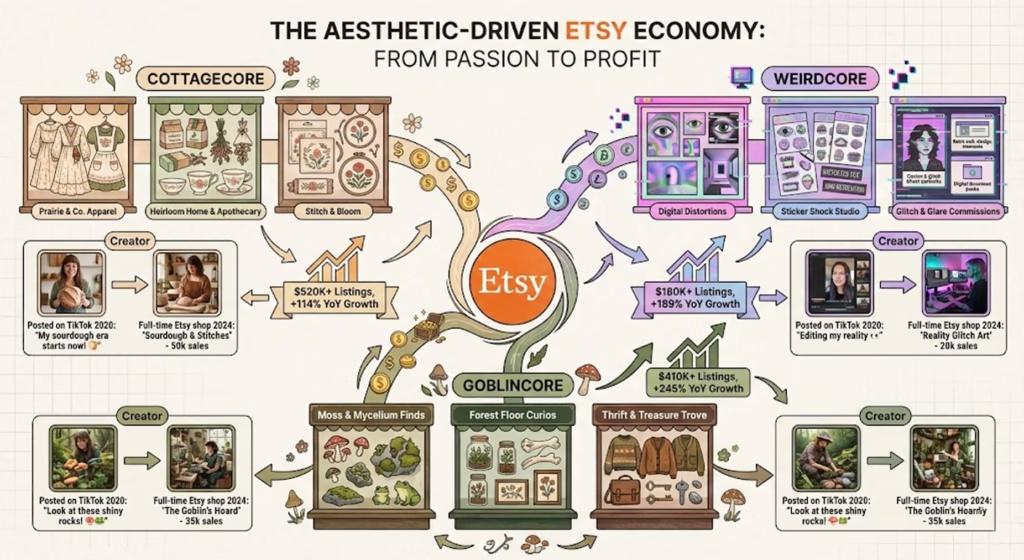

The monetization of aesthetics reveals tensions between anti-capitalist values and market reality.

Etsy ecosystem exploded around these aesthetics. Small businesses emerged selling cottagecore dresses, goblincore pins, weirdcore stickers, aesthetic-specific art prints, and curated “starter kits.” Data from Shopify’s 2024 trend report showed aesthetic-aligned microbusinesses had 38% higher engagement than generic brands.

| Aesthetic | Etsy Listings (2024) | Year-Over-Year Search Growth | Average Monthly TikTok Views |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cottagecore | 520,000+ | +114% | 1.3 billion |

| Goblincore | 410,000+ | +245% | 2.1 billion |

| Weirdcore | 180,000+ | +189% | 890 million |

Creator economy enabled aesthetic entrepreneurship. Artists built followings by posting aesthetic content, then monetized through Patreon, print sales, commissions, and sponsored content. The line between authentic participation and commercial exploitation remained contested.

Criticisms of commercialization came from multiple angles. Goblincore’s “found not bought” ethos contradicts selling Goblincore products. Cottagecore’s anti-capitalism rings hollow when performed with expensive aesthetic purchases. Weirdcore stickers and prints commodify emotional processing into consumable products.

Yet many community members argue small creators selling their art differs fundamentally from corporate appropriation. Supporting independent artists aligns with anti-capitalist values more than buying from mass retailers. The nuance matters—who profits and how determines whether monetization betrays or embodies community values.

The Future of Niche Online Art Communities

As we approach 2026, these aesthetics have evolved beyond their pandemic peak. Understanding where they’re heading illuminates both their staying power and the inevitable cycles of internet culture.

Evolution and Mainstreaming (2025 Perspective)

Each aesthetic followed different trajectories from peak to present.

Cottagecore mainstreamed most completely. What started as niche Tumblr tags now appears in Target catalogs and HGTV shows. This mainstream adoption brought visibility but dilution. The aesthetic became shorthand for “vaguely vintage floral” without deeper values. Many original community members moved to more specific niches (Honeycore, Jamcore, Bloomcore) to escape commercial saturation.

Yet core communities persist. On Tumblr and Discord, long-term participants continue creating, discussing, and living Cottagecore values beyond aesthetics. The movement matured from trend to established subculture with staying power.

Goblincore maintained stronger countercultural stance, partly due to its inherent unmarketability. You can’t easily mass-produce “found objects” or sell “embracing decay.” The aesthetic’s anti-consumerist core protected it from complete appropriation. While mushroom decor exploded commercially, the deeper community practices (foraging, collecting, ecological connection) remained grassroots.

Weirdcore experienced the most volatile trajectory. After 2021-2022 peak, algorithmic fatigue set in. The aesthetic became so ubiquitous on TikTok that novelty faded. Cringe culture backlash intensified. By 2024-2025, Weirdcore posts received more eye-rolls than engagement from wider audiences.

However, Weirdcore evolved rather than died. The aesthetic splintered into more specific variations (Liminalcore, Backroomscore, Analogcore) while maintaining core community. Artists refined techniques, deepening rather than broadening appeal. The movement transitioned from viral trend to established digital art practice.

Next Generation Aesthetics

New aesthetics constantly emerge, some building on these foundations, others reacting against them.

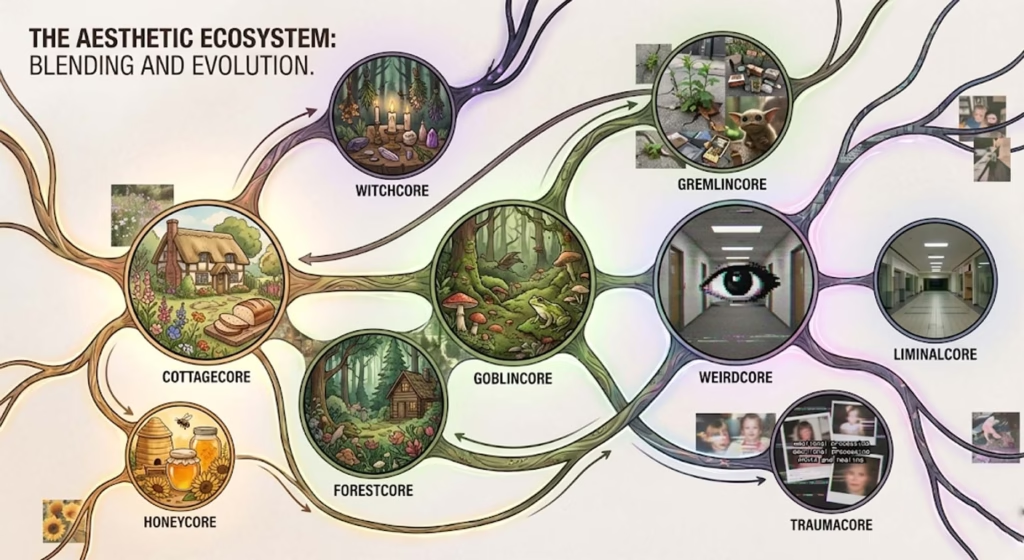

Hybrid movements combine elements from multiple aesthetics. “Witchcore” blends Cottagecore’s naturalism with darker mysticism. “Gremlincore” merges Goblincore’s chaos with more urban, digital elements. These hybrids demonstrate how aesthetics cross-pollinate and evolve.

Platform-specific aesthetics emerge from new technologies and features. BeReal spawned authenticity-focused aesthetics rejecting Instagram curation. Discord server aesthetics developed around community spaces rather than public performance. Each new platform potentially births new visual languages.

Recognizing patterns in successful aesthetics reveals what makes them stick. They must: address genuine psychological or social needs, offer accessible entry points (anyone can participate), provide clear but flexible visual language, enable authentic community formation, and avoid requiring extensive resources (economic accessibility matters).

Failed aesthetics often lack these elements. Overly complex visual requirements exclude participants. Aesthetics without values beyond visuals lack depth. Those requiring expensive purchases contradict contemporary values. Community formation requires more than shared visuals—it needs shared meaning.

Lasting Impact on Digital Culture

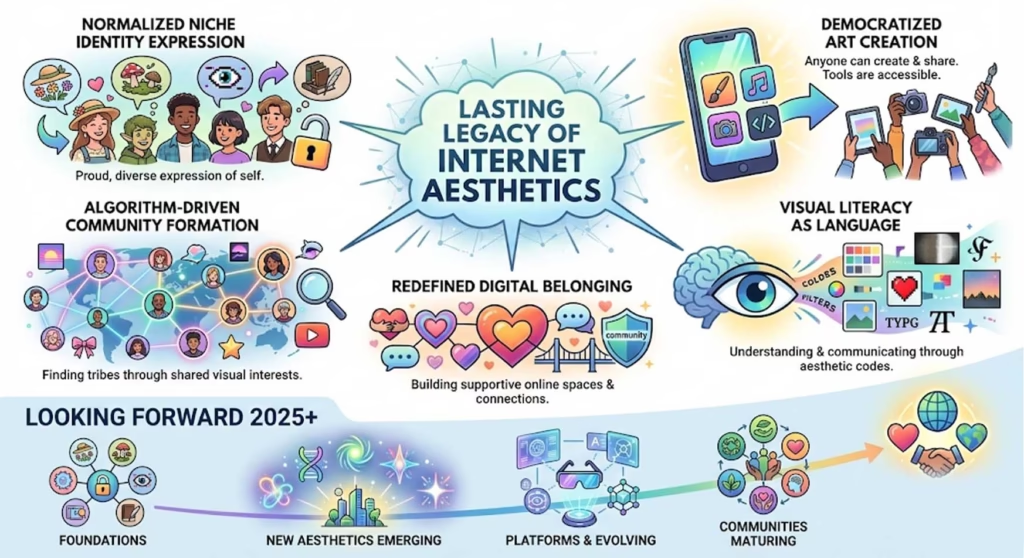

Regardless of individual aesthetic longevity, their collective impact permanently changed digital culture.

Niche identity expression became normalized. Pre-2020, declaring yourself part of a micro-aesthetic seemed bizarre. Now it’s standard—everyone has their niche, their aesthetic, their community. This normalization enables authentic self-expression for those who never fit mainstream categories.

Algorithm-driven community formation is accepted reality. People expect algorithms to surface their people, their aesthetics, their interests. The idea that platforms should show you what you’ll love (not just what’s popular) reshaped expectations for digital spaces.

Visual literacy increased dramatically. Gen Z reads aesthetic codes fluently—recognizing Cottagecore vs. Goblincore vs. Weirdcore at a glance, understanding the values and communities each signals. This literacy functions as language, enabling sophisticated communication through visual choice.

Digital art democratization accelerated. These movements proved you don’t need formal training or expensive equipment to create meaningful art. Phone cameras, free apps, and authentic vision suffice. This accessibility expanded who gets to participate in art-making from exclusive few to anyone interested.

Practical Guide: Understanding and Engaging

For those wanting to understand or participate in these communities beyond surface level, practical guidance helps navigate the landscape thoughtfully.

How to Identify Each Aesthetic

Visual identification requires attention to specific markers rather than vague vibes.

Cottagecore identifiers:

- Soft, warm color palette (pastels, earth tones, gentle)

- Nature imagery emphasizing beauty (flowers, sunshine, gardens)

- Domestic/rural settings (cottages, kitchens, countryside)

- Vintage or vintage-inspired elements

- Emphasis on handmade, natural materials

- Overall mood: gentle, cozy, romanticized

Goblincore identifiers:

- Muddy, earthy color palette (browns, greens, oranges)

- Nature imagery emphasizing overlooked elements (mushrooms, moss, decay)

- Focus on small creatures (frogs, snails, worms)

- Collections of found objects, “shinies”

- Worn, thrifted, mismatched aesthetics

- Overall mood: chaotic, earthy, authentically messy

Weirdcore/Dreamcore identifiers:

- Digital, manipulated imagery (obvious editing)

- Liminal spaces, empty locations

- Eyes as prominent motif

- Cryptic text overlays

- VHS/glitch/lo-fi digital aesthetics

- Childhood nostalgia with uncanny elements

- Weirdcore mood: unsettling, eerie, wrong

- Dreamcore mood: whimsical, nostalgic, surreal-but-comforting

Common confusions:

- Cottagecore with general vintage = Cottagecore specifically emphasizes rural/natural elements

- Goblincore with general grunge = Goblincore specifically celebrates nature’s chaos, not urban decay

- Weirdcore with general surrealism = Weirdcore specifically uses digital/internet nostalgia and liminal spaces

Participating Authentically

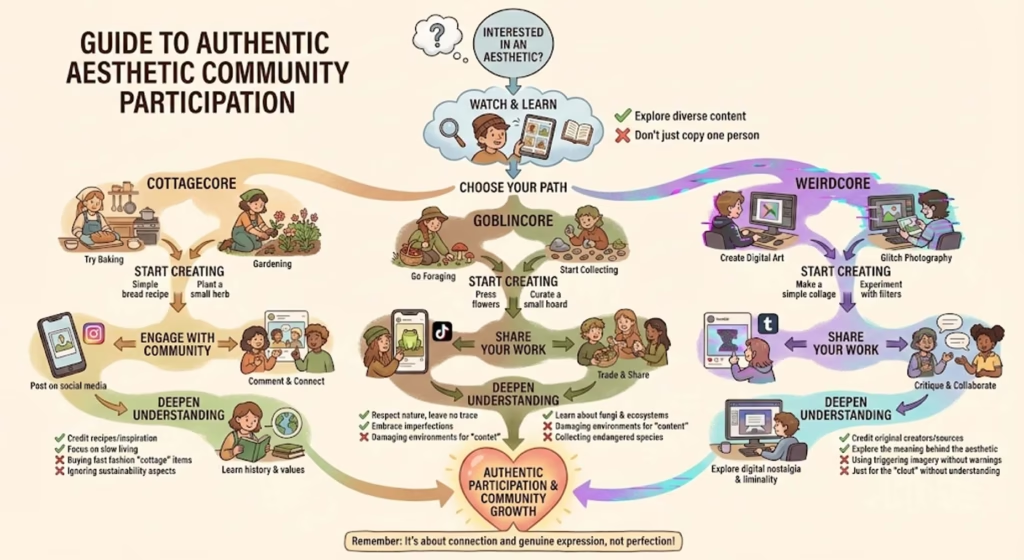

Authentic participation requires understanding values, not just copying visuals.

Community etiquette basics:

- Learn the values and history before claiming the identity

- Engage with existing community content (comment, share, discuss)

- Create, don’t just consume (even small contributions matter)

- Credit inspiration and sources

- Respect subcommunity-specific norms (each Reddit, Discord, TikTok community may have different expectations)

- Avoid aesthetic tourism (dipping in for content without genuine interest)

For Cottagecore:

- Acknowledge the LGBTQ+ roots and current community

- Engage with sustainability and anti-consumerism values

- Recognize privilege in rural fantasies

- Support small creators over fast fashion cottagecore

- Actually try baking, gardening, or crafting—it’s about practices, not just aesthetics

For Goblincore:

- Practice ethical foraging (never take more than you need, learn species)

- Understand the anti-consumerist foundation (find, don’t buy)

- Be aware of antisemitic goblin tropes (avoid perpetuating harmful stereotypes)

- Embrace actual chaos—it’s not curated mess but genuine acceptance

- Connect with real nature, including the “ugly” parts

For Weirdcore:

- Understand it processes real psychological experiences (not just random weird)

- Avoid romanticizing mental illness

- Learn the visual language beyond surface (eyes, liminal spaces have meanings)

- Create from genuine emotion, not just copying aesthetics

- Engage with the analog horror and surrealist traditions informing it

Finding Your Community

Different platforms host different aspects of aesthetic communities.

TikTok for:

- Discovering your aesthetic through FYP algorithm

- Quick tutorials and inspiration

- Trend participation

- Hashtags: #cottagecore #goblincore #weirdcore #dreamcore

Tumblr for:

- Deep community discussion

- Long-form content and theory

- Historical community roots

- Tags function as gathering spaces

Discord for:

- Intimate community connection

- Real-time chat and collaboration

- Community projects and events

- Friend-making beyond public performance

Reddit for:

- Advice and resource sharing

- Community standards discussions

- Subreddits: r/cottagecore r/goblincore

Pinterest for:

- Visual inspiration and moodboarding

- Tutorial and how-to discovery

- Planning aesthetic projects

Instagram for:

- Curated aesthetic presentation

- Following specific creators

- Grid cohesion for your own aesthetic

Safety and privacy considerations:

- You don’t have to share your face or real name

- Separate aesthetic accounts from personal if desired

- Be aware of age-appropriate spaces (some communities skew young)

- Report and block harmful behavior

- Remember: people online aren’t always who they present as

Critical Engagement

Participating thoughtfully means engaging with both appeal and problems.

Recognizing problematic elements:

- Cottagecore: Watch for whitewashing rural history, colonial nostalgia, Tradwife adjacency

- Goblincore: Be aware of antisemitic goblin imagery, appropriation of indigenous knowledge

- Weirdcore: Notice when trauma/mental illness becomes aesthetic rather than processing

Engaging with criticisms:

- Read critical perspectives from marginalized community members

- Consider how your participation might perpetuate harm

- Support creators working to decolonize and diversify aesthetics

- Call in (not call out) when seeing problems

- Accept that enjoying something doesn’t require defending its every aspect

Balancing participation with awareness:

- You can love Cottagecore while acknowledging its Eurocentric bias

- You can practice Goblincore while being careful about goblin stereotypes

- You can create Weirdcore while not romanticizing dissociation

- Authentic participation includes critical reflection

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Cottagecore and why did it become popular?

Cottagecore is an internet aesthetic celebrating romanticized rural life, featuring soft pastels, bread-baking, gardening, and vintage fashion inspired by pre-industrial countryside living. It exploded during the 2020 COVID lockdowns as people sought psychological escape from global chaos. The aesthetic provided a sense of control and simplicity when everything felt overwhelming—you couldn’t control the pandemic, but you could control your sourdough starter. Its popularity reflects deeper Gen Z yearnings for slower living, connection to nature, and escape from capitalism’s relentless productivity demands.

How is Goblincore different from Cottagecore?

While Cottagecore romanticizes pristine pastoral beauty—sunlit meadows, perfect bread, coordinated florals—Goblincore celebrates nature’s chaotic, “ugly” elements like mushrooms growing from decay, mud, interesting rocks, and small creatures others overlook. Where Cottagecore seeks curated control and aesthetic perfection, Goblincore embraces messy acceptance and finds beauty in what conventional standards reject. As one community member put it: “Goblincore is Cottagecore for people who actually spend time in nature, who know that nature isn’t just sunshine and pretty flowers—it’s mud and bugs and things rotting, and that’s beautiful too.” Goblincore also centers neurodivergent acceptance and anti-consumerist values more explicitly than Cottagecore.

What exactly is Weirdcore and Dreamcore?

Weirdcore is a digital aesthetic featuring distorted, low-resolution imagery, surreal text overlays, and unsettling visuals that evoke early internet nostalgia and liminal unease. Common elements include oversized eyes poorly edited onto scenes, empty liminal spaces like abandoned playgrounds, VHS glitches, and cryptic messages. It aims to create feelings of confusion and disorientation. Dreamcore uses similar visual techniques—hazy bright imagery, surreal elements, distorted childhood locations—but seeks comfort and wonder rather than unease. Think of Weirdcore as unsettling surrealism that makes you feel something’s wrong, while Dreamcore is whimsical surrealism that feels strangely familiar and comforting. Both process internet-age childhood memories and psychological experiences unique to growing up online.

Are these just trends or actual art movements?

These function as both. They’re collaborative art movements with distinct visual languages, creative communities producing original work, philosophical values and meaning beyond aesthetics, and lasting cultural influence on fashion, design, and digital art. However, they also experience commercialization, mainstream adoption, and the typical lifecycle of internet trends. Their staying power varies—Cottagecore has largely mainstreamed, Goblincore maintains stronger countercultural identity, and Weirdcore evolved into more specific subgenres. What makes them more than simple trends is their role in identity formation, genuine community building, and democratization of art-making. The communities themselves create meaning beyond the visuals.

Why are these aesthetics popular with LGBTQ+ and neurodivergent people?

These communities offer belonging and acceptance for marginalized identities in ways mainstream culture often doesn’t. Cottagecore attracts woman-loving-woman communities because it allows reclaiming domestic life from patriarchal expectations—creating queer utopian spaces where women love women, tend gardens together, and build lives outside heteronormative structures. Goblincore’s explicit “no gender, only bugs” ethos rejects binary gender performance entirely, celebrating people who feel they don’t fit conventional gender boxes. The aesthetic’s appreciation for collecting, hoarding, and chaos resonates with neurodivergent people whose behaviors are often pathologized—suddenly your seventeen interesting rocks aren’t “too much,” they’re a valued collection. Weirdcore processes dissociation and derealization experiences common among neurodivergent people and those with trauma. These aesthetics create spaces where traits considered “weird” or “wrong” become valuable and celebrated.

How do I participate in these communities?

Start by consuming content authentically—follow hashtags on TikTok (#cottagecore, #goblincore, #weirdcore), explore Tumblr tags, browse Pinterest boards. Notice what resonates emotionally, not just visually. Then create using accessible tools: Cottagecore might mean baking something and photographing it with your phone, Goblincore could be documenting mushrooms you find on a walk, Weirdcore involves free photo editing apps adding surreal elements to images. Share your creations and engage with others’ work through comments and discussions. Join Discord servers or subreddit communities for deeper connection. Remember that authentic participation means understanding values and practices, not just copying aesthetics. It’s better to genuinely connect with one aesthetic’s community than performatively sample all three.

What platforms are best for each aesthetic?

TikTok dominates all three but serves different purposes—Cottagecore for cozy lifestyle tutorials and romanticized moments, Goblincore for foraging adventures and collection showcases, Weirdcore for short surreal video pieces. Tumblr remains crucial for in-depth community discussion, long-form content, and historical roots of all three aesthetics. Instagram works well for Cottagecore’s curated visual presentation and Goblincore’s nature photography. Pinterest excels at moodboarding and inspiration gathering across all aesthetics. Discord provides intimate community spaces for real conversation and collaboration beyond performative public posts. Reddit offers advice-sharing and community standards discussion. Choose platforms based on how you want to engage—quick inspiration (TikTok), deep discussion (Tumblr), visual curation (Instagram/Pinterest), or genuine community (Discord).

Can these aesthetics be problematic?

Yes, and acknowledging problems enables more thoughtful participation. Cottagecore faces criticism for Eurocentric bias (romanticizing specifically Western European rurality), whitewashing brutal historical realities of rural life, potential appropriation by far-right Tradwife movements, and class privilege in “cottagecore lifestyle” requiring resources most lack. Goblincore risks perpetuating antisemitic stereotypes through goblin imagery if handled carelessly, appropriating indigenous foraging knowledge without credit, and romanticizing poverty when thrifting is necessity not choice. Weirdcore/Traumacore can romanticize mental illness, making dissociation and trauma into aesthetic consumption rather than genuine processing. Engaging critically means enjoying these aesthetics while acknowledging their problems, supporting creators working to address these issues, and reflecting on your own participation’s potential impacts.

How have these aesthetics influenced mainstream culture?

Their influence extends far beyond internet spaces. Fashion runways incorporated Cottagecore prairie dresses and pastoral elements, fast fashion brands launched dedicated “cottagecore collections,” and designers like Simone Rocha and Batsheva built careers around these aesthetics. Interior design shifted from minimalist Scandinavian to maximalist naturalism—dried flowers, rattan furniture, abundant plants. Musicians created albums steeped in these aesthetics (Taylor Swift’s folklore being most prominent). Video games like Animal Crossing and Stardew Valley exploded in popularity aligned with cottagecore values. UX/UI design now incorporates earthy tones, moss textures, and deliberately amateur aesthetics from these movements. They’ve normalized niche identity expression, demonstrated algorithm-driven community formation, and democratized digital art creation. Even as individual aesthetics wax and wane, their collective impact permanently changed how people create and find belonging online.

Are these aesthetics still relevant in 2025?