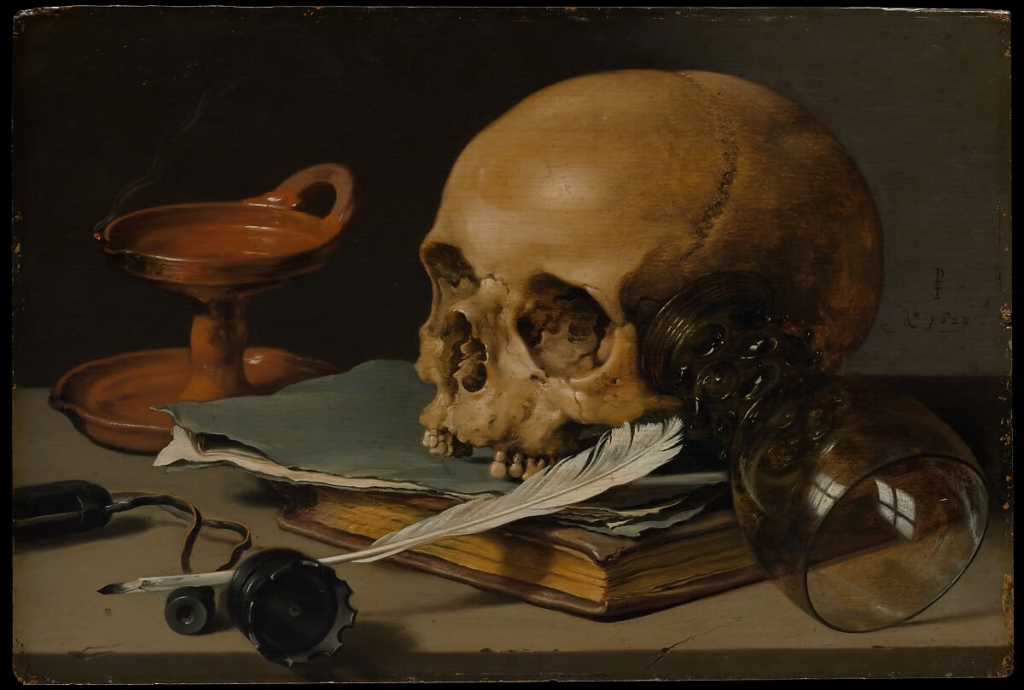

Imagine standing before a 17th-century Dutch painting. On the table before you: gleaming silver vessels, exotic fruits from distant colonies, expensive Chinese porcelain—and a human skull staring back at you. This jarring combination wasn’t accidental. It was a calculated moral message from an artist navigating the tension between unprecedented wealth and spiritual devotion.

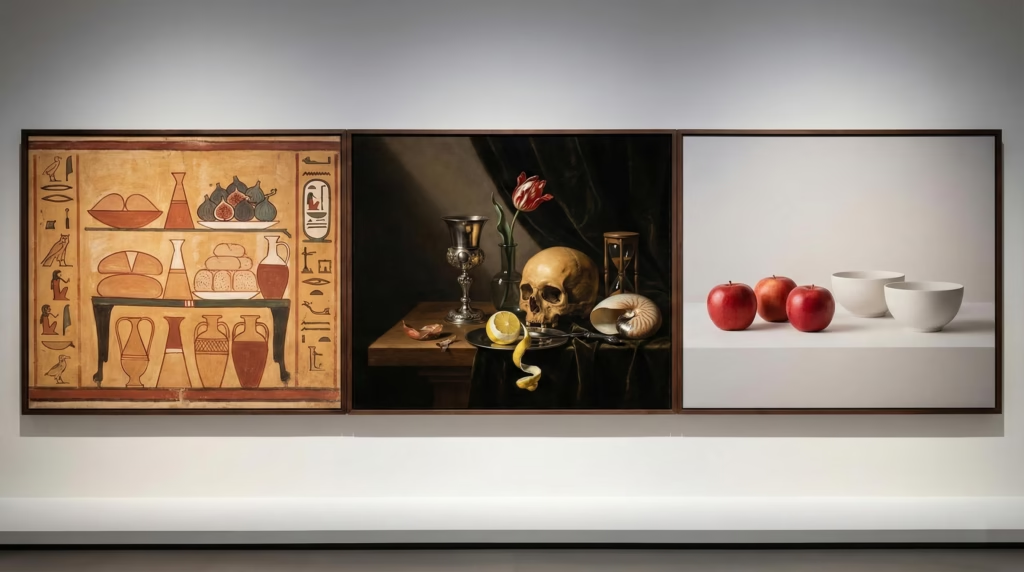

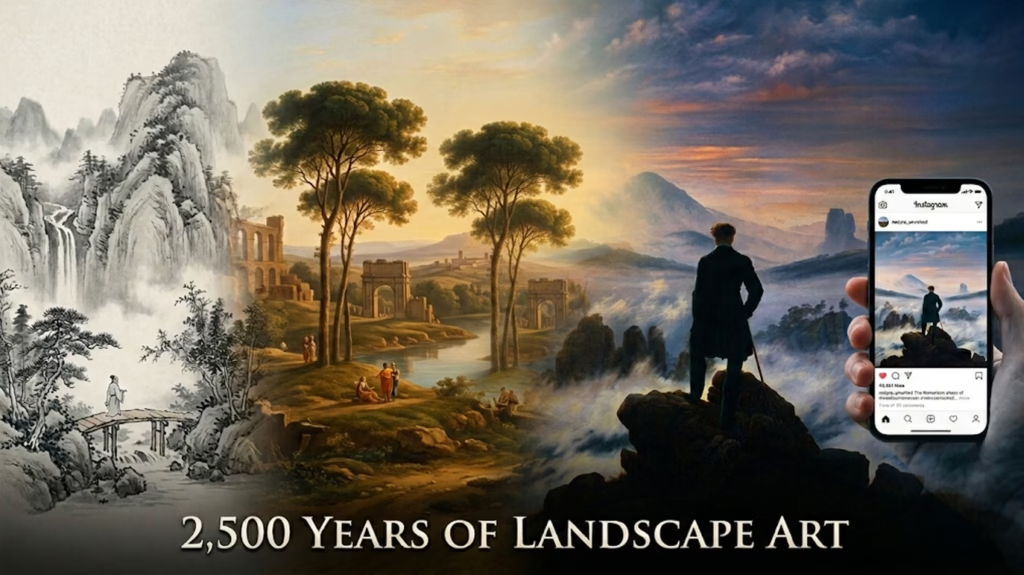

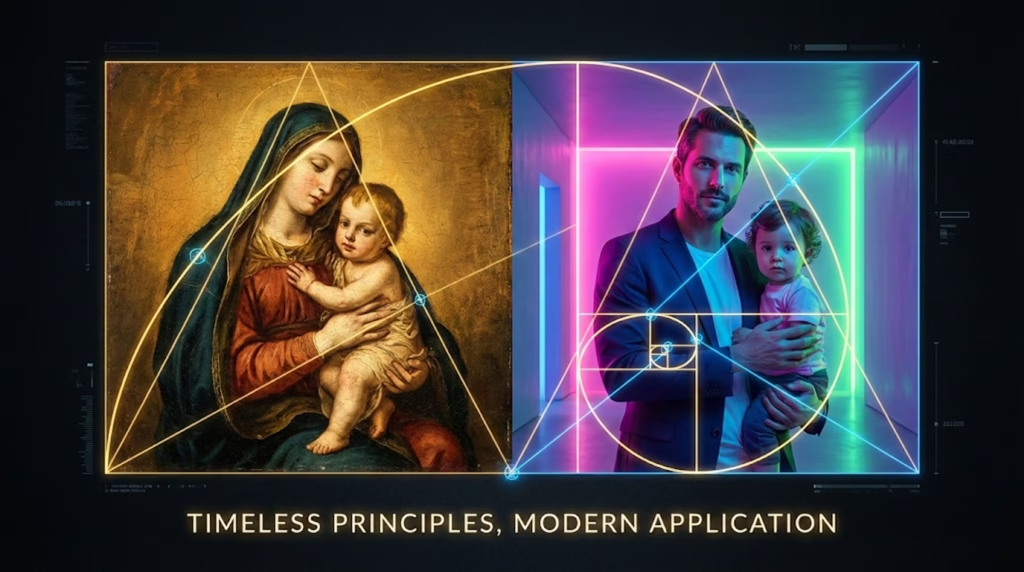

This is the fascinating paradox at the heart of still life painting. For over 4,000 years, artists have transformed the humble table into a stage for exploring humanity’s most enduring questions: What is true value? How should we live? What happens when we die? The objects arranged on these painted tables—bread, grapes, silver vessels, skulls—conveyed radically different messages in ancient Rome, Renaissance Florence, Protestant Amsterdam, and contemporary galleries.

In this comprehensive guide, you’ll discover how still life artwork evolved from Egyptian tomb offerings meant to sustain the dead, to Dutch moral warnings about earthly vanity, to modern critiques of consumer culture. You’ll learn to decode the symbolic language that turns a simple bowl of fruit into a profound meditation on mortality, or an arrangement of luxury goods into a sermon about spiritual values.

We’ll journey through ancient civilizations, explore the explosive creativity of the Dutch Golden Age, examine how women artists excelled within constraints, and see how contemporary artists subvert traditional meanings. By the end, you’ll possess a systematic framework for reading any still life painting you encounter—understanding not just what objects appear, but why they mattered to the people who painted and commissioned them.

Drawing on analysis of major works from the Metropolitan Museum, Rijksmuseum, National Gallery, and extensive scholarly research on art history, economics, and cultural contexts, this guide reveals how the table became Western art’s primary battleground where wealth and morality performed their eternal dance.

What is Still Life Painting? Defining the Genre

Before diving into four millennia of history, we need to understand what qualifies as still life and why this seemingly simple genre captivated artists and patrons across cultures and centuries.

The Origins of “Still Life” – From Dutch “Stilleven”

The term “still life” emerged in the 17th-century Netherlands, derived from the Dutch word stilleven—literally “still life” or “motionless life.” This terminology arose precisely when the genre was reaching its artistic and cultural peak in Protestant Holland. The Dutch needed a word to describe this new type of painting that depicted arrangements of inanimate objects rather than the grand historical or religious narratives that dominated European art.

Other European languages developed their own terms, each revealing cultural attitudes toward the genre. Italians called it natura morta (“dead nature”), emphasizing the lifeless quality of the subjects. This somewhat morbid terminology reflected Italian academic preferences for depicting living human figures in action—the highest form of art according to Renaissance hierarchy. Spanish artists used bodegón, meaning “tavern” or “storeroom,” connecting the genre to humble domestic spaces and everyday sustenance rather than aristocratic grandeur.

The French adopted nature morte, mirroring the Italian emphasis on stillness and absence of life. These linguistic variations hint at different cultural relationships with material objects and their representation. The Dutch term, with its neutral observation of “things that are still,” perhaps best captures the genre’s essential quality: the concentrated attention on objects at rest, frozen in time for contemplation.

Core Characteristics That Define Still Life

At its most basic, still life depicts inanimate objects as the primary subject matter. These objects typically fall into several categories: natural items like fruits, vegetables, flowers, dead game, fish, or shells; human-made objects including glassware, ceramics, books, musical instruments, or jewelry; and symbolic items such as skulls, hourglasses, or candles carrying specific meanings.

What distinguishes still life from other genres containing objects is that these inanimate items form the painting’s main focus, not background details supporting a narrative about human figures. A portrait showing a scholar surrounded by books isn’t still life—it’s portraiture using props. But a painting of those same books arranged on a table with no human presence? That’s still life.

The genre offered artists remarkable compositional freedom. Unlike portraiture, where clients expected flattering likenesses, or religious painting, where iconography followed strict conventions, still life allowed experimentation with arrangement, lighting, and color relationships. Artists could move objects at will, test different compositions, study how light transformed surfaces, and explore spatial relationships without the constraints of depicting recognizable people or stories.

This freedom attracted artists across skill levels and circumstances. Still life became the perfect training ground for mastering technical challenges: How do you paint transparent glass convincingly? How do you render the subtle texture of a peach’s skin? How do you make silver appear to reflect light? The genre demanded and developed virtuoso skill in depicting materials, textures, and the effects of light—techniques artists could then apply to more “elevated” subjects.

Still Life’s Place in the Hierarchy of Genres

Despite—or perhaps because of—its popularity with both artists and buyers, academic authorities ranked still life at the bottom of painting’s hierarchy. In 1667, French art theorist André Félibien, affiliated with the prestigious French Academy, formalized what had been implicit European attitudes. His influential ranking placed history painting (depicting historical, mythological, or biblical narratives with multiple figures) at the top, followed by portraiture, then landscape and animal painting, with still life occupying the lowest position.

The reasoning reflected classical humanist values: paintings of human beings engaged in important actions were inherently more worthy than paintings of “dead things without movement.” Still life required no knowledge of human anatomy, no understanding of complex narratives, no moral or educational purpose—it was merely skilled craft rather than elevated art. As Félibien wrote, depicting inanimate objects placed an artist far below those who “become imitators of God in representing human figures.”

Yet this hierarchical dismissal created a fascinating paradox. Precisely because still life ranked low academically, it attracted enormous commercial demand. Middle-class buyers who couldn’t afford large history paintings or prestigious portraits could purchase beautiful, skillfully executed still lifes for their homes. The paintings required no education to appreciate—anyone could recognize and enjoy a luscious arrangement of fruit or flowers. They were decorative, affordable, and didn’t carry the weight of aristocratic patronage.

This “inferior” status also created opportunities for artists excluded from academic training, particularly women. Academic painting required access to life drawing classes with nude models—strictly forbidden to women. Still life could be practiced at home, with arranged objects posing no impropriety. Ironically, some women still life painters, like Rachel Ruysch, commanded higher prices than celebrated male painters including Rembrandt.

The hierarchy’s academic dismissal versus commercial success reveals a crucial truth: still life’s power came from its accessibility and intimacy. These were paintings about the material world people actually inhabited—their tables, their possessions, their daily encounters with beauty and mortality. That connection proved more compelling than any academic ranking.

Ancient Beginnings: Wealth, Offerings, and the Afterlife (3000 BCE – 500 CE)

Still life painting didn’t begin with Dutch masters. Its roots reach back to humanity’s earliest efforts to preserve and honor material goods, revealing how different civilizations understood the relationship between objects, wealth, and the spiritual realm.

Egyptian Tomb Paintings – Providing for Eternity

The ancient Egyptians created the first known still life images, painting elaborate arrangements of food and provisions on tomb walls throughout the Nile Valley. These weren’t decorative choices but essential spiritual provisions. Egyptians believed that items depicted in tomb paintings would magically become real in the afterlife, sustaining the deceased through eternity.

The Tomb of Menna, dating to around 1400 BCE in the Theban Necropolis, offers one of the most comprehensive examples. Menna served as “Scribe of the Fields” during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose IV, overseeing agricultural production. His tomb walls display abundant still life elements: heaps of grain representing his administrative responsibility, carefully rendered fish from the Nile, cuts of meat, loaves of bread, jars of beer, and baskets of fruits.

These Egyptian still lifes followed strict conventions. Artists depicted objects from their most recognizable angles—fish shown in profile, bread loaves from the side, baskets from above. The goal wasn’t realistic three-dimensional representation but clear identification. Would the deceased recognize this as bread in the afterlife? That mattered more than capturing realistic shadows or perspective.

The arrangements emphasized abundance and provision. Tables groaned under the weight of offerings. Quantities mattered because they represented not just sustenance but status—demonstrating the deceased’s wealth and ensuring they maintained their social position eternally. Even in death, material prosperity signaled spiritual importance.

This creates the first recorded instance of objects on tables carrying dual meaning: practical sustenance and status display. The boundary between “what you need” and “what you own” blurred. Wealth became spiritual preparation. The table transformed from functional furniture into a staging ground for demonstrating one’s relationship with both the material and divine worlds—a role it would continue playing for millennia.

Greco-Roman Still Life – Symbols of Prosperity

Ancient Greeks and Romans developed still life in dramatically different directions. Rather than spiritual provisions, their still life elements served as decorative celebrations of earthly abundance and refined taste. The shift reflected fundamental philosophical differences—from Egyptian preparation for an afterlife to Greco-Roman appreciation of present pleasures.

Roman wall paintings and floor mosaics unearthed at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Villa Boscoreale showcase remarkable technical sophistication. The famous “Still Life with Glass Bowl of Fruit and Vases” from a Pompeii villa (circa 70 CE) demonstrates impressive mastery of perspective, shading, and realistic representation that wouldn’t be matched again until the Renaissance.

These Roman still lifes featured the motif that would become iconic across centuries: a transparent glass bowl overflowing with fruit—grapes, apples, figs, pomegranates—arranged to suggest natural abundance. The glass itself represented technological achievement and wealth. The specific fruits carried symbolic resonance: grapes connected to Bacchus (god of wine) and the pleasures of symposia; pomegranates to Persephone and seasonal cycles; figs to fertility and Mediterranean prosperity.

Decorative mosaics called emblema, found in wealthy Roman homes, showcased the range of foods enjoyed by the upper classes. These weren’t just artistic choices but social communications. Your mosaic floor depicting exotic game, imported fruits, fine wine, and varied seafood announced to visitors: “I can afford these luxuries. I participate in trade networks spanning the empire. I live well.” The table, even in representation, broadcast class status.

Roman still life also introduced trompe l’oeil—paintings designed to “deceive the eye” by appearing three-dimensionally real. Pliny the Elder recorded the legendary competition between Greek painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis supposedly painted grapes so realistic that birds tried to eat them. Parrhasius countered with a painted curtain so convincing that Zeuxis tried to pull it aside. Whether historically accurate or not, the story reveals ancient appreciation for still life’s ultimate technical challenge: making painted objects indistinguishable from real ones.

Crucially, Romans also began using skulls in artwork, often accompanied by the Latin phrase “Omnia mors aequat”—”Death makes all equal.” This early memento mori tradition acknowledged that regardless of one’s wealth (symbolized by the feast), mortality comes to everyone. The skull on the table introduced tension that would define still life for centuries: material abundance versus spiritual awareness, present pleasure versus inevitable death, wealth that cannot prevent fate.

What These Ancient Tables Tell Us

Comparing Egyptian and Roman approaches reveals two fundamentally different relationships between objects, wealth, and meaning. Egyptian tomb still lifes were deeply spiritual—material goods served metaphysical purposes, ensuring comfort in an afterlife conceived as continuation of earthly existence. Wealth wasn’t display but provision. Tables bore offerings for gods and sustenance for souls.

Roman still lifes were predominantly social—material goods communicated status among the living. Wealth became display itself. Tables showcased taste, access, and participation in empire-wide prosperity. Even when skulls appeared, reminding viewers of mortality, the context remained this-worldly: enjoy what you have while you can.

Yet both traditions established patterns that would echo through still life history. Both used tables as stages for arranging objects with meaning beyond their utility. Both understood that what appears on a table—whether tomb offering or dinner party mosaic—communicates values and beliefs. Both recognized that careful arrangement transforms random objects into deliberate statements.

The dual function emerged clearly: objects could signify spiritual preparation (Egypt) or social position (Rome), devotion or display, humility or pride. This tension—between objects as vehicles for transcendent meaning versus objects as markers of worldly success—would reach its most sophisticated expression 1,600 years later in Protestant Holland. But the fundamental question was already present in ancient still life: When we arrange precious things on a table, are we preparing our souls or advertising our status?

Medieval Transition: Objects in Service of Faith (500-1400 CE)

During the Middle Ages, still life retreated from independence into the service of religious narrative. Yet this period, often dismissed in art historical accounts of the genre, actually developed crucial techniques and symbolic frameworks that enabled still life’s later flourishing.

Religious Symbolism Dominates

Medieval Christian worldview left little room for celebrating material objects for their own sake. Art existed primarily to glorify God, teach biblical stories to largely illiterate populations, and reinforce Church authority. Paintings of simple objects seemed frivolous when artists could instead depict Christ’s passion, saints’ martyrdoms, or the Virgin Mary’s grace.

Still life elements didn’t disappear—they went undercover. Objects appeared within religious scenes as symbolic reinforcements of Christian messages. A painting of the Last Supper necessarily included bread and wine, but these weren’t still life—they were the Eucharist, Christ’s body and blood. Lilies in Annunciation scenes weren’t botanical studies but symbols of Mary’s purity. Skulls in paintings of St. Jerome weren’t memento mori objects but references to Golgotha and meditation on mortality as path to salvation.

Northern European artists, particularly Flemish and Dutch painters, showed special fascination with rendering these symbolic objects in minute, realistic detail. Jan van Eyck’s religious paintings included extraordinarily precise depictions of objects—metalwork, textiles, fruit, flowers—painted with almost obsessive attention to surface textures and light effects. His “Arnolfini Portrait” (1434), while primarily a portrait, features fruit on the windowsill and a convex mirror reflecting the room—both elements demonstrating his interest in objects as worthy of careful study.

This religious context established symbolic vocabularies still used centuries later. Specific fruits, flowers, and objects acquired fixed meanings through repeated association with biblical stories:

- Bread = body of Christ (Eucharist)

- Wine/grapes = Christ’s blood; also earthly pleasure and Bacchus (dual meaning)

- Apples = original sin, Eve’s temptation in Eden

- Pomegranates = resurrection (many seeds = many souls rising)

- Roses = Virgin Mary, martyrdom, divine love

- Lilies = purity, especially Mary’s virginity

- Cherries/strawberries = fruits of paradise, souls of the blessed

Medieval artists didn’t invent these associations—many drew from biblical texts, classical literature, and early Christian interpretation. But through repetitive visual pairing (Virgin Mary + lilies, St. Jerome + skull), these symbols became deeply embedded in European visual literacy. An educated viewer automatically “read” objects as carrying specific Christian meanings.

Illuminated Manuscripts – Training Ground for Realism

While large-scale still life remained rare, miniature still life elements flourished in illuminated manuscripts’ decorative borders. Books of Hours, Psalters, and other devotional texts featured elaborate margins filled with flowers, insects, fruits, shells, and small animals painted in astonishing detail.

The “Hours of Catherine of Cleves” (circa 1440), created in Utrecht, exemplifies this tradition’s sophistication. Its borders contain meticulously rendered strawberries, violets, columbines, acorns, butterflies, snails, and other natural objects painted with scientific precision. These weren’t random decoration—they carried symbolic weight supporting the texts they framed. But they also demonstrated that artists could depict objects realistically when they chose to.

This manuscript work proved crucial for still life’s development. First, it trained artists in close observation and precise rendering of natural objects. The tiny scale demanded extraordinary skill—mistakes in a thumb-sized painting were as obvious as on a wall-sized fresco. Second, it established markets for realistic depictions of flowers, fruits, and objects among wealthy patrons who commissioned these luxury books. Third, it created overlap between manuscript illuminators and panel painters, allowing techniques to cross-pollinate.

Artists working on both manuscripts and larger paintings—common in Early Netherlandish art—brought their observational skills to progressively larger formats. The jump from painting a realistic strawberry in a manuscript margin to painting a realistic strawberry on a panel as an independent subject wasn’t enormous. The technical foundation already existed.

Preparing the Ground for Renaissance Independence

Medieval art’s contribution to still life history often gets overlooked because objects rarely appeared independently. Yet this period established essential prerequisites for the genre’s emergence:

Technical development: Artists mastered rendering textures, capturing light on surfaces, depicting transparent and reflective materials, and creating three-dimensional illusion on two-dimensional surfaces. These skills, honed on religious subjects and manuscript borders, made hyperrealistic still life possible.

Symbolic vocabulary: The association of specific objects with specific meanings became so ingrained that viewers automatically interpreted visual symbols. This created shared language—artists could communicate complex ideas through carefully chosen objects rather than words or narratives.

Collector interest: Wealthy patrons demonstrated willingness to pay for realistic depictions of beautiful objects, whether in manuscript borders or as details in larger works. The market existed; it just needed redirection toward independent still life paintings.

Philosophical groundwork: Late medieval thought, particularly scholasticism’s emphasis on studying creation to understand Creator, began validating close observation of natural world as potentially spiritual activity. This subtle shift opened conceptual space for paintings of objects to carry devotional weight.

By 1400, all pieces were positioned for still life’s emergence as independent genre. Artists possessed technical skills, symbolic vocabularies, interested patrons, and theological justification. They needed only the cultural shifts of Renaissance humanism and Protestant Reformation to fully liberate objects from subordinate roles.

The table remained largely absent during medieval period—food appeared in biblical feast scenes, but domestic table settings rarely featured. Yet when tables finally emerged as still life’s primary stage in the 16th-17th centuries, they inherited medieval Christianity’s symbolic system. Dutch Protestant painters would arrange Catholic symbol vocabularies into new moral messages, using the same bread, grapes, and skulls but inverting their meanings from salvation signifiers to warnings against worldly attachment.

Renaissance Awakening: Still Life Becomes Independent (1400-1600)

The Renaissance’s emphasis on humanism, nature study, and artistic innovation finally allowed still life to emerge as a genre in its own right. Yet even as objects gained independence from religious narratives, they remained steeped in symbolic meaning.

Early Renaissance Still Life – Testing Independence

Art historians traditionally credit Jacopo de’ Barbari’s “Still Life with Partridge and Gauntlets” (1504) as the earliest surviving pure still life painting from the modern era. This small oil-on-limewood panel depicts a dead partridge pierced by a crossbow bolt, hanging alongside two iron gauntlets against a plain background. The vertical composition and stark presentation mark it as fundamentally different from objects within narrative scenes.

The painting likely carried symbolic weight—the partridge possibly representing peace or sacrifice, the military gauntlets suggesting war, the crossbow bolt connecting them in violent juxtaposition. But the key innovation was isolating these objects as the painting’s entire subject. No human figures, no religious story, no landscape—just objects arranged for contemplation.

Around the same time, Leonardo da Vinci created watercolor studies of fruit and plants (circa 1495) as part of his restless scientific examination of nature. While Leonardo conceived these as preparatory studies rather than finished artworks, they demonstrated Renaissance interest in observing and recording natural objects precisely. His approach combined artistic rendering with proto-scientific investigation—measuring, analyzing, understanding how things worked.

Albrecht Dürer similarly created extraordinarily detailed botanical watercolors, including his famous “The Large Piece of Turf” (1503). This study of common plants—dandelions, yarrow, meadow grass—rendered with almost photographic precision showed that “humble” subjects deserved serious artistic attention. The watercolor balanced chaos (wild plant growth) with order (carefully observed structure), characteristics that would define still life for centuries.

These early Renaissance examples shared tentative quality—artists testing whether objects alone could sustain viewer interest, whether paintings needed human presence or narrative to matter. The answer, as developing markets proved, was no. Beauty, skill, and meaning could reside in a carefully painted cabbage as much as a biblical scene.

New Symbolic Frameworks Emerge

As Renaissance humanism celebrated human achievement and natural world study, symbolic frameworks for objects began expanding beyond purely Christian interpretations. Objects now could signify intellectual pursuit, artistic refinement, and worldly knowledge alongside spiritual meanings.

Books, previously associated primarily with sacred texts and monastic learning, began appearing as symbols of broader humanist education. A painted stack of books might reference classical literature, philosophy, mathematics, or new scientific texts flooding from printing presses. The book itself became a symbol of the revolutionary idea that knowledge could be widely distributed, studied by laypeople, challenged and expanded.

Musical instruments appeared with increasing frequency, signifying cultural sophistication and artistic sensibility. A lute didn’t just reference David’s psalms anymore—it suggested the owner’s participation in courtly culture, musical education, and appreciation for beauty. These instruments also carried erotic overtones through their curving, body-like forms and association with seduction through music.

Flowers and fruits began shedding some religious associations to become valued for decorative beauty and seasonal representation. The four seasons could be depicted through characteristic plants: spring bulbs, summer roses, autumn grapes, winter holly. This allowed paintings to celebrate natural cycles without necessarily invoking Christian resurrection symbolism.

Significantly, objects associated with emerging scientific methods appeared: globes (geography), quadrants (astronomy), hourglasses (measuring time), coins (commerce). Renaissance still life began reflecting an expanding world—trade routes reaching Asia and the Americas, scientific instruments revealing nature’s mechanisms, wealth flowing from banking and commerce rather than just land ownership.

Yet religious symbolism didn’t vanish—it coexisted with secular meanings. The same pomegranate could reference both Persephone (classical myth) and resurrection (Christian symbol) depending on context and viewer. This symbolic multiplicity enriched objects’ potential meanings while demanding more sophisticated interpretation from audiences.

Technical Breakthroughs Enable Genre

The development of oil painting technique by Jan van Eyck and other Netherlandish artists revolutionized what was possible in depicting objects. Unlike tempera or fresco, oil paint dried slowly, allowing extended working time. Artists could blend colors seamlessly, build up transparent layers (glazing), and achieve luminous effects impossible with faster-drying media.

This technical revolution particularly benefited still life. Capturing the bloom on a grape’s surface, the transparency of glass, the complex reflections on polished silver, the subtle color variations in fabric folds—all required the control and blending capacity oil painting offered. Artists could work from direct observation, adjusting their paintings over days or weeks as they studied how light transformed objects.

The slow drying also enabled unprecedented precision. A painter could render individual hairs on a peach’s skin, water droplets on flower petals, or the crystalline structure of salt. This hyperrealism became still life’s calling card—proof of virtuoso skill that couldn’t be dismissed even by critics favoring “higher” subjects.

Northern European artists particularly excelled at these techniques. Flemish and Dutch painters developed methods for depicting specific material textures so convincingly that viewers could identify objects by surface quality alone. Velvet looked different from satin, silver different from pewter, Delft pottery different from Chinese porcelain. This material specificity allowed paintings to function as precise records of valuable objects while demonstrating technical mastery.

Tables as Sites of Learning and Culture

As still life emerged as independent genre, tables began appearing as its natural stage. The shift reflected changing domestic architecture and social practices. Medieval great halls with communal trestle tables gave way to Renaissance chambers with permanent furniture including tables designated for specific activities—dining, writing, studying, displaying collections.

The scholar’s desk became a popular still life setting. Paintings depicted tables laden with books, writing implements, scientific instruments, and study lamps—the tools of humanist intellectual life. These arrangements proclaimed the owner’s participation in the Republic of Letters, their serious engagement with learning, their status as educated rather than merely wealthy.

Similarly, tables displaying collections of natural specimens (shells, minerals, fossils) or artificial curiosities (carved ivories, medals, rare coins) reflected the cabinets of curiosity craze. Wealthy collectors assembled these “wonder rooms” to demonstrate their knowledge of the world’s diversity and their access to rare objects. Still life paintings of such collections functioned as both inventory records and status displays.

The table itself carried symbolic weight. In an era when most people still ate from boards laid across trestles, a permanent table represented stability, civilization, and refinement. The objects arranged on that table—whether books, scientific instruments, or valuable specimens—communicated the owner’s identity and values.

Renaissance still life thus established the table as more than furniture. It became a stage for performing identity through objects, a boundary between public presentation and private use, a surface where material culture could be curated to communicate meaning. This conceptual framework set the stage for the genre’s explosive development in the following century, when Dutch artists would transform tables into philosophical battlegrounds where wealth and morality confronted each other directly.

The Dutch Golden Age: When Wealth Met Morality on the Table (1600-1700)

The 17th century witnessed still life painting’s most sophisticated and prolific development in the Dutch Republic. Here, in the world’s first modern capitalist society, artists navigated profound tensions between Protestant spiritual values and unprecedented material prosperity. The table became the ultimate stage for this moral drama.

The Perfect Storm – Why Holland Dominated

Multiple forces converged in the Dutch Republic to create ideal conditions for still life’s flourishing. Understanding these contexts illuminates why Dutch artists developed the genre so extensively and why their works carried such complex symbolic freight.

Economic miracle: The Dutch Republic emerged from its independence war with Spain (1568-1648) as Europe’s dominant commercial power. The Dutch East India Company controlled spice trade routes to Asia. Dutch ships carried goods worldwide. Amsterdam became the continent’s financial center. This unprecedented wealth flowed not primarily to aristocrats but to an urban merchant middle class.

Protestant Reformation values: Dutch Calvinism emphasized hard work, modest living, and suspicion of Catholic “idolatry” in religious art. Images of saints and biblical narratives became problematic. Churches stripped decoration, leaving whitewashed walls. This created demand for secular subjects—portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, and still lifes—suitable for private homes rather than churches.

The profound paradox: Dutch merchants became wealthy through God-given opportunities in trade and commerce. Calvinism taught that prosperity might signal divine favor—the Protestant work ethic blessed success. Yet that same theology warned against worldly attachment, material pride, and forgetting that earthly life was temporary. How could you celebrate God’s blessings (wealth) while maintaining spiritual humility (detachment)?

Urban middle-class buyers: Unlike aristocratic patronage systems elsewhere in Europe, Dutch art markets served thousands of prosperous merchants, bankers, shop owners, and skilled craftspeople. Art historian John Michael Montias estimates that between 1580 and 1800, approximately 5,000 Dutch artists produced 9-10 million paintings. This massive output required broad demand. Still lifes were perfect—affordable, decorative, requiring no classical education to appreciate, suitable for homes of modest size.

Technical excellence: Dutch artists achieved unparalleled skill in rendering materials and light. The combination of oil painting mastery, direct observation, and intense artistic competition produced works of breathtaking realism. A painted glass goblet looked wet. Silver gleamed. Fruit appeared edible. This technical virtuosity made still lifes desirable as demonstrations of Dutch cultural achievement.

These converging forces—wealth, theology, commerce, and skill—created a society uniquely positioned to make still life central to its visual culture. Dutch painters didn’t just paint objects well; they used objects to work through their culture’s deepest anxieties and contradictions.

Types of Dutch Still Life – A Taxonomy

Dutch still life divided into several distinct categories, each with characteristic subjects, compositions, and implied messages. Understanding these types helps decode any Dutch painting you encounter.

Ontbijtjes (Breakfast Pieces): The most modest category depicted simple morning meals. A typical ontbijtje might show a table with bread, cheese, herring, butter, a knife, and beer or wine in simple glass. These pieces emphasized restraint and Protestant moderation. The foods were local, the vessels modest, the message clear: appreciate simple sustenance rather than luxurious excess.

Pieter Claesz specialized in ontbijtjes, creating compositions in muted browns and golds that emphasized humble foods’ textures and forms. His paintings showed meals interrupted—a half-eaten roll, knife resting at angle, glass partially emptied. This suggested both the transience of consumption (the food will be gone) and the mortality of the eater (who may not finish their meal).

Banketjes (Banquet Pieces): A step up in elaboration, banketjes depicted more substantial meals with multiple courses and finer serving pieces. These might include oysters (expensive delicacies), imported lemons, better quality wine, and silver rather than pewter vessels. The paintings walked a fine line—showing prosperity without descending into ostentatious display.

Willem Claeszoon Heda mastered this category, creating carefully balanced compositions featuring expensive but not extravagant items. His paintings often showed banquets after the diners departed, with disorder suggesting completed celebration—overturned glasses, peeled fruit, rumpled tablecloths. This “aftermath” quality added melancholy notes; the pleasure has passed, the guests have left, time moved forward.

Pronkstilleven (Ostentatious Still Life): Here restraint disappeared. Pronkstilleven translated roughly to “ostentatious still life” or “sumptuous still life,” and these paintings reveled in luxury.

Typical elements included:

- Nautilus shells mounted in elaborate silver holders

- Chinese porcelain imported at great expense

- Tropical fruits (pineapples, oranges) from colonies

- Ornate Venetian glassware

- Persian carpets

- Precious metal vessels and elaborate serving pieces

- Exotic parrots or other colonial specimens

Jan Davidsz. de Heem created some of the most elaborate pronkstilleven, composing vast horizontal canvases where objects sprawled across tables in controlled abundance. Willem Kalf favored darker backgrounds with dramatic lighting, making precious objects emerge from shadows like treasures revealed.

The pronkstilleven posed the sharpest challenge to Protestant humility. These paintings unabashedly displayed wealth, demonstrating the patron’s access to global trade networks, refined taste, and substantial resources. Yet even here, symbolic warnings often appeared—a watch reminder of passing time, subtle decay on fruit, carefully placed mortality symbols moderating the celebration.

Vanitas: The explicitly moralizing category, vanitas paintings delivered clear warnings about earthly life’s transience and material pleasures’ futility. The term came from the Biblical Book of Ecclesiastes: “Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas”—”Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.”

Vanitas compositions combined luxury objects with explicit mortality symbols:

- Skulls (ultimate memento mori)

- Extinguished or smoking candles

- Hourglasses or pocket watches

- Soap bubbles (fragility, brevity)

- Wilting or dead flowers

- Rotting fruit

- Overturned or empty vessels

- Broken instruments

David Bailly, Harmen Steenwyck, and Pieter Claesz created powerful vanitas works. The university town of Leiden became particularly associated with this genre, perhaps because theological faculties and educated viewers particularly appreciated explicit moral messaging.

The vanitas formula seemed straightforward: display wealth, then undercut it with death reminders, forcing viewers to contemplate mortality. But the very act of painting luxury goods so beautifully somewhat undermined the message. Viewers could simultaneously enjoy visual pleasure in rendered textures and acknowledge the moral point—the paintings thus participated in the very worldly attachment they warned against.

The Table as Moral Theater – Reading Dutch Paintings

Dutch still life painters used compositional techniques to communicate meaning beyond just object symbolism. Learning to read these visual cues unlocks deeper interpretation.

Light symbolism: Dramatic side-lighting (chiaroscuro, influenced by Caravaggio) created strong contrasts between illumination and shadow. Light often suggested divine presence or spiritual awareness, while shadows represented worldly concerns or moral darkness. Objects emerging from darkness into light underwent symbolic transformation—revealed, examined, spiritually illuminated.

Disorder as message: Carefully orchestrated disarray communicated meaning. An overturned wine glass suggested pleasure consumed and finished. A peeled lemon with its rind dangling showed hidden bitterness beneath sweet appearance—a metaphor for life’s disappointments or false promises. A half-eaten roll indicated interrupted sustenance, perhaps by death’s arrival. This “disorder” was actually precisely controlled to suggest narrative and moral lessons.

Reflections and hidden images: Dutch painters brilliantly exploited reflective surfaces to add layers of meaning. Silver vessels often reflected windows, the painter at work, or even tiny scenes from outside the painting’s primary composition. Glass balls contained entire rooms in distorted miniature, sometimes with the artist visible. These reflections suggested multiple perspectives, the unreliability of appearances, or the painter’s acknowledgment of their role in creating illusion.

Pieter Claesz’s “Vanitas Still Life with Violin and Glass Ball” (circa 1628) exemplifies this technique. The glass ball reflects a window and the artist himself at his easel, inserting meta-commentary about artistic creation into the moral message about mortality. The inclusion suggests: “I, the artist, transcend time through my work even as I acknowledge death’s inevitability.”

Temporal markers: Dutch painters obsessed over time’s passage. Smoking candles just extinguished suggested life’s recent ending—death could have occurred moments ago. Watches showed specific times, inviting viewers to contemplate hours ticking away. Hourglasses represented measurable time running out. Flowers in various states—some blooming, others wilting, petals fallen—depicted beauty’s decay in real time.

This temporal consciousness created dramatic tension. The painting itself was timeless, potentially lasting centuries. Yet it depicted objects explicitly marked by time’s destructive passage. The medium itself (permanent oil painting) contradicted the message (nothing lasts). This paradox generated much of Dutch still life’s power.

Decision framework for viewers:

When encountering Dutch still life, ask:

- What’s the light doing? Bright/celebratory or dark/somber? Where does it come from? What does it illuminate versus leave in shadow?

- How much disorder appears? Tidy arrangements suggest control and order. Disarray suggests narrative—something happened, someone left, time passed.

- What’s the wealth level? Simple foods and vessels = modest Protestant values. Exotic expensive objects = wealth display. Both present = tension.

- What mortality symbols appear? More skulls/decay/time markers = stronger moral warning. Absence suggests pure celebration or aesthetic focus.

- Is there specific decay? Wilting flowers, rotting fruit, or empty vessels add memento mori weight even without skulls.

Most sophisticated Dutch still lifes combined multiple messages simultaneously, allowing viewers to appreciate technical skill, enjoy visual beauty, contemplate mortality, and acknowledge wealth—all at once. This multiplicity made them perfect for Dutch merchant culture: you could display your success while professing your piety, all in a single purchase.

Master Artists and Their Approaches

The Dutch Golden Age produced remarkable still life specialists, each developing distinctive styles and approaches while working within established conventions.

Pieter Claesz (1597-1660): Claesz mastered the art of the monochromatic still life, creating compositions in muted browns, golds, and grays that emphasized form and texture over color. His breakfast pieces and vanitas works featured careful diagonal compositions that drew the eye across the table surface while maintaining perfect balance.

His technical brilliance appeared in how he rendered reflections. Silver tazzas (standing dishes) in his paintings reflected windows with such precision you could count their panes. Glass roemers (wine glasses) captured distorted room interiors. This virtuosity demonstrated both technical mastery and symbolic awareness—reflections showed reality’s complexity, the world’s appearance versus truth, the unreliability of surface judgments.

Willem Claeszoon Heda (1595-1680): Heda specialized in “banquet aftermath” scenes—tables after the feast, with evidence of consumption but diners departed. His compositions often featured expensive silver, fine crystal, and imported foods, but arranged with restraint suggesting measured enjoyment rather than excess.

Heda excelled at rendering transparency and reflection. His glass goblets appeared wet, their sides catching and bending light convincingly. Halved lemons showed juice glistening. Silver platters reflected neighboring objects with optical accuracy. This technical precision made his paintings function almost as scientific studies of how light behaves while simultaneously delivering moral messages about moderation.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684): De Heem created the most elaborate and abundant still life compositions of the Dutch Golden Age. Working primarily in Antwerp (technically Flemish, but deeply influenced by Dutch traditions), he developed wide horizontal formats to accommodate sprawling arrangements of fruits, flowers, expensive vessels, and luxury objects.

His paintings combined Dutch technical precision with Flemish love of abundance and color. A single de Heem composition might include thirty different fruits, multiple flower varieties, ornate silver, Chinese porcelain, and live insects exploring the arrangement. Despite this complexity, his compositions maintained harmony through careful color orchestration and balanced distribution of visual weight.

Willem Kalf (1619-1693): Kalf revolutionized the pronkstilleven by pairing it with dramatic dark backgrounds. His paintings typically featured small groupings of extraordinarily precious objects—nautilus shell cups, Chinese porcelain bowls, ornate golden vessels, exotic fruits—emerging from near-total darkness in pools of warm light.

This chiaroscuro approach created theatrical drama. Objects glowed against black backgrounds like treasures revealed in candlelight. The darkness suggested mystery, the unknown, perhaps even moral shadow surrounding material wealth. Yet the beauty of the illuminated objects was undeniable—Kalf made wealth visually seductive even while the dark backgrounds hinted at vanitas themes.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750): The most commercially successful Dutch still life painter of her era, Ruysch specialized in flower paintings that combined scientific accuracy with artistic beauty. Her father was a botanist and anatomy professor, giving her access to rare specimens and training in close observation.

Ruysch’s compositions featured asymmetrical arrangements—flowers cascading diagonally across dark backgrounds, creating dynamic movement rather than static balance. She frequently painted flowers from different seasons in single bouquets (roses with tulips with fall asters), creating impossible arrangements that showcased breadth of knowledge rather than single-moment accuracy.

Her flowers showed various life stages: tight buds, full blooms, wilting specimens, fallen petals. Insects explored her compositions—butterflies, beetles, ants—adding both scientific interest and memento mori symbolism (decay, transformation). Ruysch’s paintings commanded prices higher than Rembrandt’s during her lifetime, demonstrating that technical mastery could overcome gender barriers in art markets.

Clara Peeters (c.1589-1657): Peeters pioneered a revolutionary technique: painting tiny self-portraits reflected in polished surfaces within her still lifes. In her works featuring elaborate table settings, careful examination of silver knife handles, glass goblets, or metal vessels reveals miniature images of a woman painter at her easel.

This insertion transformed the paintings from pure object study to meta-commentary on artistic creation and female authorship. By literally painting herself into her works, Peeters claimed artistic authority in an era when women painters faced dismissal as mere copyists or amateurs. The technique said: “I made this. I observed this. I possess the skill to render this—and myself rendering it.”

Decoding Dutch Symbols – Comprehensive Guide

Dutch still life developed an elaborate symbolic vocabulary. Understanding these symbols unlocks layers of meaning in paintings.

Food Items:

Bread – Most commonly the body of Christ (Eucharist), connecting daily sustenance to spiritual nourishment. In secular contexts, honest food representing modest living.

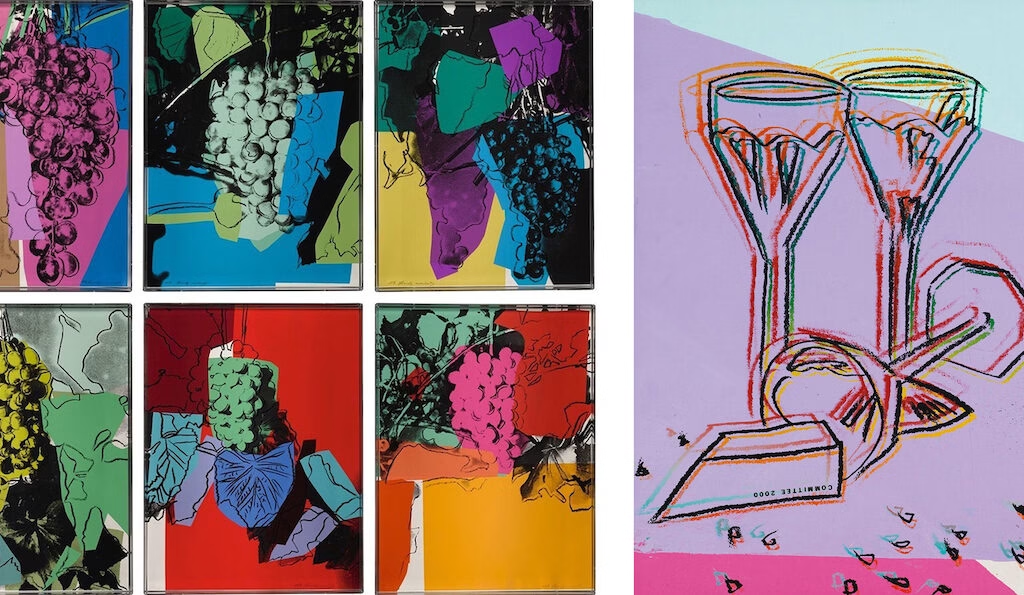

Grapes – Dual symbolism: Christian wine/blood of Christ; also Bacchus and worldly pleasure, specifically drunkenness and sensual excess.

Pomegranates – Many seeds representing many souls; Christian resurrection. Also Persephone myth; exotic import demonstrating trade wealth.

Lemons (especially peeled) – Bright exterior hiding sour interior; life’s disappointments, false promises, bitterness beneath attractive surface.

Cherries/Strawberries – Fruits of paradise, sweetness of heaven, souls of the blessed in Christian iconography.

Oysters – Sexual connotation (aphrodisiac), also emptiness (shell without life), luxury food demonstrating coastal economy.

Fish – Christian symbol (ichthys), also Dutch maritime economy, abundance from the sea.

Cheese – Dutch production pride, local prosperity, humble food supporting moral restraint message.

Objects of Wealth:

Silver and gold vessels – Material success, refined taste, participation in global trade. When paired with mortality symbols: transient worldly achievement.

Chinese porcelain – Exotic luxury demonstrating Dutch East India Company trade reach, refined taste for Far Eastern aesthetics, substantial wealth required for acquisition.

Persian carpets – Colonial wealth, appreciation for Islamic artistic traditions, status symbol requiring significant resources.

Venetian glass – Refined taste for Italian luxury goods, fragility (easily broken = life’s fragility), transparency allowing optical effects.

Nautilus shells – Rare collectibles showing natural wonder, spiral form suggesting life’s journey, mounted in silver to demonstrate wealth.

Tulips – During tulip mania (1636-37), extraordinary wealth and speculation bubble; after crash, reminder of economic folly and inflated values.

Mortality Symbols (Memento Mori):

Skulls – Ultimate reminder: “you will die.” Often placed at eye level forcing confrontation with mortality.

Hourglasses – Time literally running out, measurable countdown to death, sand falling representing life slipping away.

Pocket watches – Life measured in moments, time’s relentless passage, modern version of hourglass for wealthy patron.

Extinguished candles – Life snuffed out, light/soul departed, recent death (still smoking = just happened).

Smoking oil lamps – Same as candles but even more dramatic—wisp of smoke suggesting soul’s recent departure.

Wilting flowers – Beauty fades, youth doesn’t last, life’s stages from bloom to decay visible.

Rotting fruit – Decay inevitable, external beauty hiding internal corruption, time’s destructive power.

Empty/overturned glasses – Pleasure consumed and gone, life poured out, celebration finished.

Knowledge & Culture:

Books – Learning, wisdom, humanist education. In vanitas context: vanity of earthly knowledge compared to divine truth.

Musical instruments – Cultural refinement, arts appreciation, courtly sophistication. Broken strings: time’s threads broken, beautiful sound silenced.

Violins specifically – Sensuality (body-like curves), beauty that fades, pleasure that ends.

Globes (terrestrial/celestial) – Worldly knowledge, exploration, science, understanding creation.

Scientific instruments – Enlightenment pursuits, reason, studying God’s creation, intellectual achievement.

Nature Elements:

Butterflies – Resurrection and transformation (caterpillar to butterfly = spiritual rebirth), soul taking flight, beauty.

Flies/insects – Decay, corruption, death’s approach, breakdown of organic matter.

Dragonflies – Worldly concerns preying on spiritual awareness, predatory nature, illusion.

Snails – Virgin Mary (believed to reproduce asexually); also sloth, slow steady decay.

Peacocks – Immortality (flesh supposedly incorruptible), also vanity (displaying beauty).

Parrots – Exotic colonial possessions, tropical wealth, colorful decoration, Dutch global reach.

Specific Flowers:

Roses – Love (red), martyrdom (blood), Virgin Mary, also transience (petals fall quickly).

Lilies – Purity, resurrection, Virgin Mary’s virginity, Easter celebration.

Tulips – Wealth, bubble economy, Dutch pride in cultivation, beauty’s cost.

Sunflowers – Devotion, turning toward God/light, faithfulness, constancy.

Poppies – Sleep, death, oblivion, forgetfulness, peace.

Daisies – Innocence, simplicity, childhood, purity.

The sophistication of Dutch symbolism lay in how objects’ meanings shifted with context. A grape in a simple breakfast piece reinforced Eucharistic associations. The same grape in a pronkstilleven alongside other luxuries suggested excess. In a vanitas with a skull, it warned against sensual pleasure. Artists expected educated viewers to read these contextual variations.

Economic Forces Behind the Images

Dutch still life cannot be fully understood without examining the economic structures that generated both the wealth depicted and the anxiety about that wealth.

Dutch East India Company and Global Trade: Founded in 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) became history’s first multinational corporation and one of the most profitable enterprises ever. It controlled trade routes to the East Indies (modern Indonesia), monopolizing spice trade—pepper, nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon—that Europeans valued as highly as precious metals.

The VOC’s ships returned laden with Asian goods: Chinese porcelain, Japanese lacquerware, Indian textiles, tropical spices, exotic shells, rare woods. These objects flooded into Dutch homes and subsequently into Dutch still life paintings. When you see Chinese porcelain in a 1650 painting, you’re looking at VOC commerce. The nautilus shell? Brought from Indonesian waters. The oranges? Mediterranean trade via Dutch shipping. Persian carpets? Overland trade routes passing through Dutch hands.

This global commerce generated enormous wealth for merchants, investors, ship owners, and associated trades. Amsterdam became Europe’s financial capital. The stock exchange (world’s first) traded VOC shares. Letters of credit and modern banking practices developed. Wealth accumulated not in aristocratic estates but urban merchant households—exactly the market buying still life paintings.

Tulip Mania (1636-1637): Perhaps history’s first documented economic bubble, tulip mania gripped the Dutch Republic when tulip bulb prices reached absurd levels. Rare varieties sold for amounts exceeding annual skilled worker wages. People mortgaged homes to speculate in tulip futures. The market collapsed in February 1637, ruining many investors.

This episode profoundly affected still life painting. Tulips appeared frequently in Dutch flower pieces, but after the crash they carried additional weight—warnings about inflated value, speculation’s dangers, the difference between real worth and market price. A tulip in a vanitas composition warned: “This beautiful thing cost someone their fortune. Don’t mistake market price for actual value.”

Colonial Exploitation: The dark foundation of Dutch prosperity lay in colonial exploitation. VOC operations in the East Indies involved violent subjugation of local populations, forced labor, monopoly enforcement through brutal means, and ecological destruction. The Atlantic trade brought enslaved Africans to Dutch colonies in the Americas. Sugar plantations in Brazil and Guyana, worked by enslaved laborers, supplied Dutch markets.

Still life paintings rarely depicted this exploitation directly. Instead, it appeared as beautiful finished products: sugar, tropical fruits, exotic birds, luxury goods. The paintings celebrated results while obscuring processes. Modern art historians, particularly Julie Berger Hochstrasser in “Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age” (2007), have examined how these apparently innocent object paintings actually document colonial violence through what they show (luxury) and hide (extraction).

Some paintings included African servants among the luxury goods—people literally displayed as possessions alongside Chinese porcelain and silver. These images reveal the dehumanizing logic equating people from colonies with exotic commodities. The servant’s presence signaled wealth while advertising the patron’s global connections—someone who owned (or hired) African attendants participated in colonial systems.

What’s NOT Shown: Dutch still life paintings celebrated merchant wealth while carefully avoiding its sources. You never see:

- VOC ships seizing territory

- Enslaved laborers harvesting sugar

- Craftspeople producing luxury goods in exploitative conditions

- Environmental destruction from spice monopolies

- Violence maintaining trade monopolies

The paintings performed ideological work, naturalizing wealth by presenting finished products divorced from production contexts. A pineapple appeared as pure luxury object, erasing the enslaved Caribbean labor that grew it, the brutal Atlantic crossing that transported it, the colonial system that enabled it. The table became a stage for displaying spoils while hiding conquest.

The Patron’s Dilemma: Understanding these economics illuminates why Dutch patrons commissioned such symbolically complex paintings. They faced genuine moral quandaries:

“I’ve become wealthy through God-given opportunities in trade. Calvinism says prosperity might signal divine favor. But that same theology warns against pride and worldly attachment. My wealth comes partly from colonial enterprises I know are brutal, though profitable. How do I celebrate success, display taste, demonstrate piety, and acknowledge moral complexity—all simultaneously?”

The solution: commission a painting showing luxury goods (celebrating wealth) + mortality symbols (professing humility) + technical brilliance (demonstrating cultural refinement) + religious symbolism (maintaining piety). The resulting still life let patrons have it both ways—display and disavowal, pride and humility, celebration and warning.

This wasn’t hypocrisy so much as genuine moral wrestling. Dutch merchants really did struggle with these contradictions. Still life paintings became visual spaces for working through tensions their society couldn’t fully resolve. The table—laden with colonial goods, marked by mortality symbols, painted with devotional care—became the stage for this moral drama.

Variations Across Europe: Regional Approaches to the Table (1600-1750)

While the Netherlands dominated still life production, other European regions developed distinct traditions reflecting their own religious, economic, and cultural contexts.

Spanish Bodegón – Austere Spiritual Intensity

Spanish still life, known as bodegón (tavern/storeroom), developed along dramatically different lines from Dutch abundance. Where Dutch paintings often displayed dozens of objects in complex arrangements, Spanish bodegones featured stark simplicity—a few items in severe geometric compositions.

Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560-1627) pioneered this austere approach before entering a monastery in 1603. His paintings typically showed a few vegetables or fruits arranged in dark architectural niches—the sharp contrast between illuminated objects and deep black backgrounds creating almost supernatural intensity. A cabbage, quince, and carrots might be the entire composition, each rendered with meticulous attention but positioned with mathematical precision.

These paintings reflected Spanish Counter-Reformation Catholicism’s emphasis on spiritual poverty, asceticism, and finding divine presence in humble things. Unlike Dutch paintings celebrating merchant prosperity, Spanish bodegones honored simple foods and the honest workers associated with them. There was dignity in a painted cabbage—God’s creation worthy of contemplation.

Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) brought still life into hybrid genres. His “Old Woman Cooking Eggs” (1618) combined still life’s precise object rendering—eggs, pottery, glass, garlic, melon—with genre painting’s human subjects. The old woman and boy shared the composition with painstakingly painted kitchen implements and food, blurring boundaries between still life and portraiture.

Spanish bodegones carried spiritual intensity lacking in much Dutch work. The sparse compositions invited meditation rather than moral warning. A single onion, illuminated against darkness, became a subject for contemplation—God’s presence in creation’s simplest forms. This aligned with mystical traditions in Spanish Catholicism (St. Teresa of Ávila, St. John of the Cross) that found divine encounters in humble everyday experiences.

Italian Natura Morta – Between Church and Grandeur

Italian still life, called natura morta (dead nature), occupied awkward positions in a culture privileging human figures and grand narratives. Academic hierarchies were particularly rigid in Italy, birthplace of Renaissance humanism and High Renaissance figure painting. Still life seemed almost offensive to critics who valued Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling and Raphael’s Madonnas.

Yet successful Italian still life traditions emerged, particularly in Rome, Naples, and Milan. Caravaggio’s “Basket of Fruit” (circa 1595-1600) remains one of the most famous examples—a simple wicker basket filled with grapes, apples, figs, and leaves, painted with unflinching realism at exact eye level. Some fruits showed decay—worm holes, brown spots—refusing to idealize nature.

Cardinal Federico Borromeo owned this painting, appreciating it for both aesthetic and potentially religious reasons. The precise realism demonstrated God’s glory manifest in creation. The inclusion of decay acknowledged nature’s cycles. The painting rewarded extended contemplation—a spiritual exercise in patient observation.

Italian still life often featured women painters, who faced even stricter restrictions on figure study than their Northern European counterparts. Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670) created exquisite botanical still lifes in tempera on vellum, combining scientific accuracy with artistic refinement. Working for the Medici court, she documented rare specimens while creating beautiful autonomous artworks. Fede Galizia (1578-1630) produced early independent fruit still lifes that influenced later developments.

Italian natura morta generally avoided the elaborate symbolic systems of Dutch vanitas. Instead, these paintings emphasized aesthetic appreciation, scientific observation, and technical mastery. They celebrated natural beauty without necessarily layering moral warnings. This reflected Catholic comfort with material beauty as reflecting divine glory—less anxiety about worldly pleasure leading to spiritual danger.

French Refinement – Rococo Luxury Without Apology

Eighteenth-century French still life developed under aristocratic patronage quite unlike Dutch merchant markets. Where Dutch paintings navigated tension between wealth and morality, French still lifes celebrating luxury without apology.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) became the era’s preeminent still life painter, creating intimate domestic scenes featuring kitchen objects, simple foods, and everyday items. His paintings possessed extraordinary technical refinement—surfaces built through patient layering of paint, colors modulated with subtle sophistication, compositions perfectly balanced.

Chardin’s work focused on modest subjects but without moralizing. A copper pot, a few onions, a piece of bread became subjects for aesthetic contemplation. The paintings asked viewers to appreciate form, color, texture, light—pure visual qualities rather than symbolic meanings. This reflected Enlightenment interest in sensory experience and empirical observation.

Alexandre-François Desportes (1661-1743) served French royalty, creating lavish still lifes documenting their collections. His “Still Life with Silver” (c. 1715-23) depicted an array of luxury objects—ornate silver vessels, fine glassware, exotic fruits, expensive textiles—owned by the painting’s commissioner. These works functioned as inventory records and status displays, celebrating French taste and aristocratic refinement.

Unlike Dutch vanitas, French aristocratic still lifes rarely included mortality symbols. Why remind wealthy patrons of death? Instead, paintings celebrated present pleasures, documented collections, and demonstrated sophisticated taste. The French Academy’s aesthetic theories emphasized beauty, harmony, and pleasure—still life should delight the eye rather than burden it with moral lessons.

This difference reflected deeper cultural divides. Protestant Netherlands developed capitalist economics with accompanying anxieties about material success versus spiritual salvation. Catholic France maintained aristocratic hierarchies where luxury signaled proper social order. A duke’s lavish table demonstrated appropriate magnificence for his station—no spiritual crisis required.

Flemish Abundance – Market Scenes and Excess

Flanders (roughly modern Belgium) remained Catholic and Spanish-controlled during much of the period when the Dutch Republic fought for independence. This political and religious difference shaped Flemish still life toward more sensual celebration of material abundance.

Frans Snyders (1579-1657) and Adriaen van Utrecht (1599-1652) created enormous market and game scenes—tables groaning under impossible quantities of food, dead game birds by the dozen, fruits piled in lush profusion, live animals investigating the displays. These paintings overwhelmed viewers with sheer abundance, celebrating plenty rather than warning against it.

Flemish artists influenced the development of Dutch pronkstilleven. The elaborate compositions, colorful palettes, and celebration of luxury goods that appear in Dutch ostentatious still lifes drew from Flemish models. But Flemish paintings generally lacked the mortality symbols and moral undertones Dutch painters added. A Flemish hunting still life showed trophy birds beautifully rendered—impressive hunt, skilled painter, abundant game. No skulls needed.

This reflected Catholic acceptance of material display as appropriate for its context. Church interiors featured gold, precious stones, elaborate altarpieces—visual splendor glorifying God. Aristocratic tables laden with food demonstrated proper hospitality and station. The sensory world wasn’t necessarily spiritually dangerous; it could reveal God’s generous creation.

The regional variations demonstrate that still life never had a single meaning. Economic systems, religious beliefs, political structures, and cultural values all shaped what appeared on painted tables and what those appearances communicated. A grape in Madrid meant something different than in Amsterdam than in Paris—same object, different worlds.

Women and Still Life: Opportunity Within Constraint (1600-1900)

Still life painting became one of the few genres where women artists could achieve professional success and recognition during periods when they faced systematic exclusion from artistic training and most subject matter.

Why Women Were Relegated to Still Life

Academic art training centered on drawing from life, particularly nude models. These life drawing sessions formed the foundation of history painting—the most prestigious genre depicting mythological, historical, or biblical scenes with heroic nude or semi-nude figures. Women were strictly barred from these classes on grounds of impropriety.

This exclusion created a cascading barrier. Without life drawing experience, women couldn’t convincingly paint human figures. Without figure painting ability, they couldn’t produce history paintings, religious works, or even most portraits and genre scenes. The academic hierarchy that placed still life at the bottom actually opened space for women precisely because it didn’t require the training denied them.

Still life subjects could be arranged at home—flowers from gardens, fruits from markets, household objects already available. Women could work in domestic spaces without violating propriety. No travel required, no improper environments, no nude models, no scandalous subject matter. These very restrictions made still life “appropriate” for women artists while closing higher-status genres.

The association deepened through cultural assumptions linking women with domestic spheres, flowers, beauty, and decoration. Still life seemed naturally feminine—arranging flowers, setting tables, caring for household objects. This gendering both enabled women’s participation and diminished still life’s status. If women painted it, academic authorities reasoned, how important could it be?

Yet women artists transformed this constraint into opportunity, using still life as a vehicle for achieving technical mastery, commercial success, and artistic recognition that transcended gender barriers.

Women Who Excelled Despite Constraints

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) achieved the most remarkable commercial success. During her lifetime, her flower paintings commanded higher prices than works by Rembrandt. She maintained professional practice for over six decades while raising ten children, balancing family responsibilities with artistic ambition.

Ruysch’s father, Frederik Ruysch, was Amsterdam’s leading botanist and anatomy professor. This gave Rachel access to rare botanical specimens, scientific knowledge, and training in precise observation. She combined botanical accuracy with artistic composition, creating flower arrangements impossible in nature—species from different seasons blooming simultaneously in asymmetrical cascades.

Her paintings rewarded extended examination. Tiny insects explored petals. Water droplets caught light. Individual stamens visible in detailed blooms. Various life stages appeared—tight buds, full flowers, wilting specimens, fallen petals—creating temporal narratives about growth and decay. The scientific accuracy never compromised aesthetic beauty; knowledge and art perfectly integrated.

Ruysch achieved international fame, patronage from European rulers, and election to painter’s guilds normally closed to women. Her success demonstrated that technical excellence could overcome gender prejudice in art markets, if not in academic hierarchies.

Clara Peeters (c.1589-1657) pioneered innovative self-representation within still life. Her elaborate table settings and banquet pieces featured one revolutionary element: tiny reflected self-portraits in polished surfaces. Examining Peeters’ silver knife handles, glass goblets, or metal vessels reveals miniature images of a woman at her easel.

This technique asserted authorship in an era when women artists faced dismissal as mere copyists lacking creative genius. By literally painting herself into her compositions, Peeters declared: “I made this. I possess the technical skill to render these objects—and myself rendering them. I am the creative mind behind this work.” The self-portraits functioned as signatures and claims to artistic authority.

Peeters worked professionally in Antwerp, producing banquet pieces, breakfast still lifes, and fish paintings. Her career demonstrates that despite restrictions, women could establish themselves as professional artists serving commercial markets.

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) blurred boundaries between art and science. Her detailed watercolors documented butterfly and moth metamorphosis—the first person to properly record insect life cycles. She traveled to Suriname to study tropical species, creating scientific illustrations of extraordinary beauty and accuracy.

While often classified as scientific illustration rather than fine art, Merian’s work shared still life’s concerns with precise observation, careful rendering of natural specimens, and artistic composition. She published books combining her illustrations with observations, contributing to both entomology and botanical art. Her work demonstrated how supposedly “lesser” genres like still life and scientific illustration could advance knowledge while producing beautiful autonomous artworks.

Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670) worked for Italy’s powerful Medici family, creating exquisite tempera miniatures of fruits, vegetables, and botanical specimens on vellum. Her paintings combined scientific precision with artistic refinement, documenting rare species while producing works of remarkable beauty. The Medici appreciated both aspects—knowledge and aesthetics integrated.

Garzoni never married, dedicating herself entirely to artistic career. She achieved financial independence through her work and left her estate to the Academy of St. Luke in Rome. Her professional success demonstrated that women could build sustainable careers through still life even in Italy’s rigid artistic hierarchies.

Maria van Oosterwijck (1630-1693) specialized in elaborate floral still lifes often incorporating vanitas elements. Her compositions combined technical brilliance with explicit moral messaging—flowers in various life stages paired with skulls, hourglasses, and other mortality symbols. She achieved international reputation, selling works to Louis XIV of France and other European royalty.

Gender Dynamics and Domestic Symbolism

The association between women and still life created complex dynamics. On one hand, it enabled professional careers otherwise impossible. Women could claim expertise in a genre that didn’t require prohibited training, work in domestic spaces without impropriety, and sell works in commercial markets.

On the other hand, this association reinforced gender stereotypes linking women with decoration, domesticity, and inferior artistic subjects. Academic authorities used women’s concentration in still life as evidence that they lacked capacity for more elevated subjects. The genre’s low status and women’s concentration there mutually reinforced each other.

The domestic symbolism cut both ways. Tables, flowers, household objects connected to spaces women managed, suggesting natural affinity. But this “natural” association actually reflected systematic exclusion from other training. Women didn’t inherently prefer still life; they excelled in the genre available to them.

Some women artists internalized and embraced these associations, presenting themselves as particularly suited to still life’s delicate subjects. Others chafed against restrictions, using still life as a platform to demonstrate skills that could transfer to any genre if barriers were removed.

Breaking Barriers Through Mastery

Despite constraints, women still life painters achieved recognition that transcended gender. Ruysch’s prices exceeded male contemporaries’. Peeters and van Oosterwijck sold internationally. Garzoni worked for powerful patrons. This success came through undeniable technical mastery—paintings so skillfully executed that quality overcame prejudice.

The irony was profound. Academic hierarchies dismissed still life as inferior precisely because it didn’t require human figure training—the very restriction preventing women from academic entry. Yet women’s concentration in still life pushed the genre to technical heights that challenged its inferior status. If “lesser” artists producing “lesser” subjects created works commanding premium prices and international fame, perhaps the hierarchy needed reassessment.

This didn’t fundamentally challenge gender barriers. Women remained barred from life drawing, academies, and figure-based genres until late 19th-century reforms. But it demonstrated that within available opportunities, women could achieve excellence comparable to or exceeding male artists. The tragedy was the waste of talent—how many potential history painters or portraitists never developed because access was denied?

The story of women in still life reveals both the genre’s liberating potential and its constraining dimensions. It offered women artists rare professional opportunities while simultaneously marking their exclusion from “higher” subjects. Understanding this dynamic enriches our appreciation of their achievements—success despite systematic barriers, excellence within imposed constraints, recognition earned through undeniable mastery.

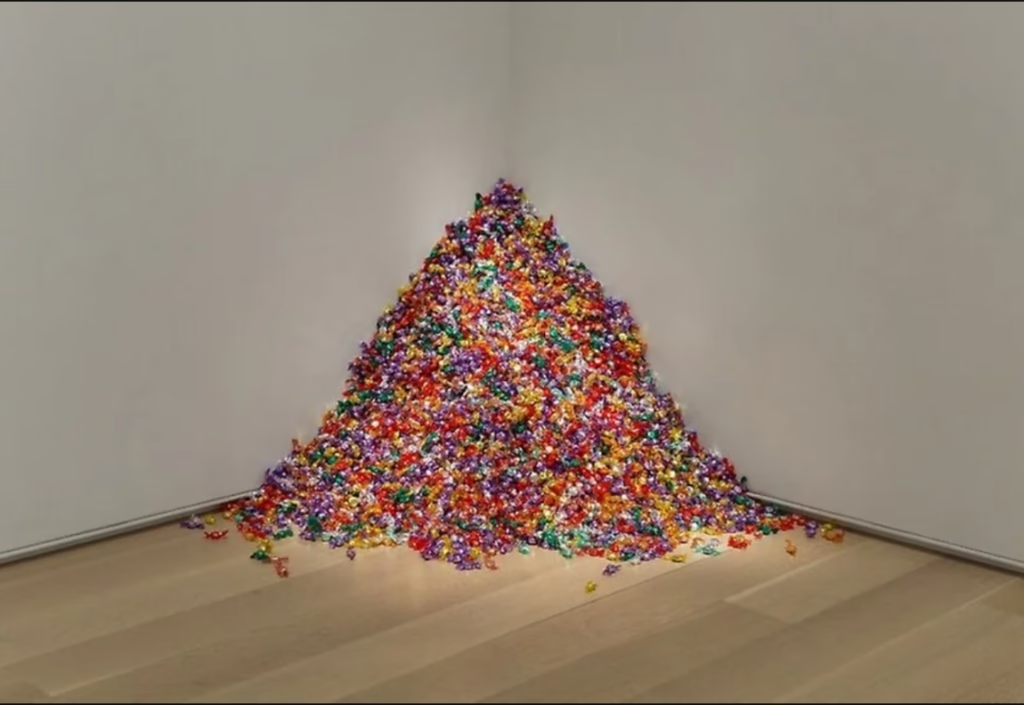

The Modern Turn: Subverting Tradition (1800-1950)

As academic hierarchies crumbled under pressure from modernist movements, artists began using still life not to communicate moral messages but to explore formal problems, experiment with technique, and challenge assumptions about representation itself.

Romantic and Realist Approaches

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) brought still life into modern painting through works that rejected academic polish in favor of direct observation and bold brushwork. His still lifes—darker and more brooding than Dutch precedents—celebrated “humble” subjects without apologizing for them. A dead rabbit, asparagus spears, or oysters became worthy subjects not despite but because of their ordinariness.

Manet famously declared that “still life is the touchstone of painting”—a provocative reversal of academic hierarchy. For Manet, mastering still life demonstrated an artist’s core abilities with color, form, composition, and observation. No narrative crutches, no grand

themes to hide behind—just the painter’s skill confronting objects directly.

Post-Impressionist Innovations

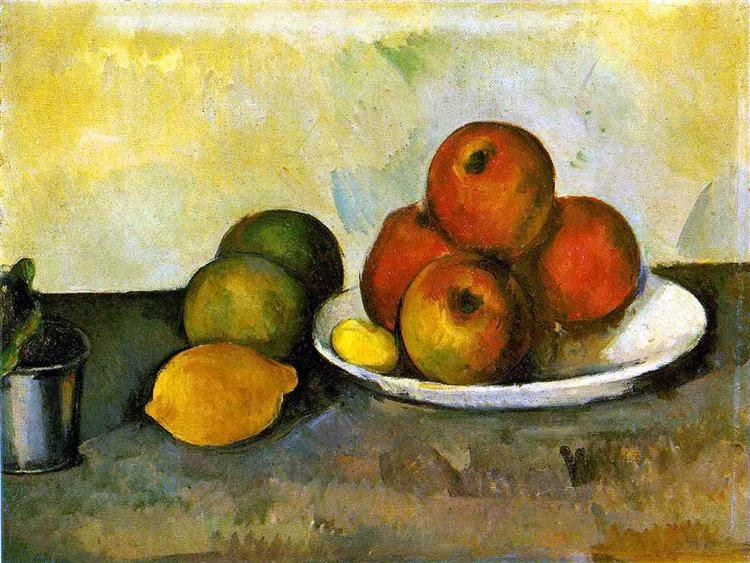

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) revolutionized still life by treating it as a laboratory for formal experimentation. His paintings deconstructed objects into geometric forms—”treating nature by cylinder, sphere, and cone,” as he advised younger artists. Multiple perspectives appeared simultaneously. Tables tilted at impossible angles. Spatial relationships refused conventional logic.

Cézanne’s still lifes showed objects not as we know them but as we see them—fractured across multiple glances, understood through accumulated observations rather than single frozen moments. His “Still Life with Skull” (1890-93) revisited vanitas traditions but with radical formal innovations. The skull coexisted with bright fruits and patterned cloth, creating visual tensions between death symbolism and vibrant color exploration.

This approach profoundly influenced Cubism. Cézanne demonstrated that representing objects didn’t require conventional perspective or single viewpoints. His work suggested painting could investigate how we see and understand objects rather than simply depicting them illusionistically.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) brought emotional intensity to still life through color and brushwork. His “Sunflowers” series (1888) transformed flowers into vehicles for expressing devotion, love, and spiritual yearning. The paintings vibrated with energy—thick impasto, saturated yellows, flowers almost writhing on canvas.

Van Gogh’s “Still Life with Bible” (1885) created deeply personal symbolism. Painted shortly before his father’s death, it showed an extinguished candle, his father’s Bible (opened to Isaiah), and a modern secular novel. The image meditated on mortality, father-son relationships, and tensions between religious tradition and modern secularism. Unlike Dutch symbolic systems legible to broad audiences, this symbolism was intensely personal—van Gogh’s private meditation made public.

Cubist Revolution – Deconstructing the Table

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque shattered still life’s representational conventions through Cubism. Their paintings fractured objects into geometric planes shown from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. A guitar appeared from front, side, and interior perspectives all at once. Tables tilted up toward picture planes. Spatial depth collapsed into flat patterns.