Imagine standing in a Renaissance anatomical theater on a cold December night in 1594. Tiered wooden benches rise steeply around you, packed with medical students, artists, and curious citizens. Below, illuminated by flickering candles, a physician makes the first incision into a cadaver—likely an executed criminal. Artists lean forward with sketch pads, racing against decomposition and fading light to capture what they see. The air is thick with the smell of decay, but also with anticipation. For the next three days, before the body becomes unusable, knowledge will flow from scalpel to sketch, from observation to understanding.

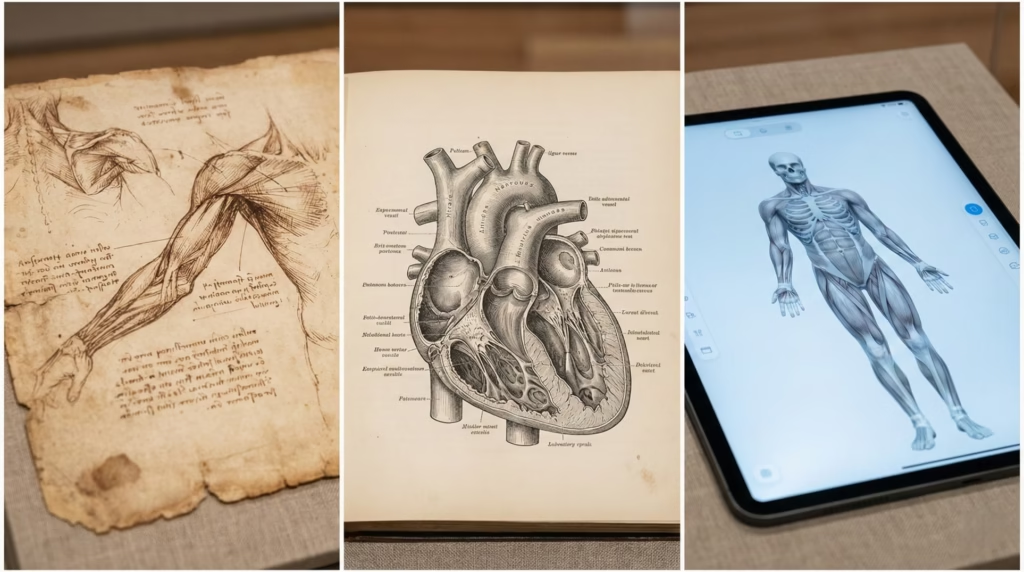

This scene captures a pivotal moment in human history—when seeing inside the human body moved from forbidden to fundamental, when artists and physicians united in their quest to understand our physical form. But this Renaissance revolution didn’t emerge from nowhere. The history of anatomical drawing spans over 2,500 years, from ancient Egyptian medical diagrams through medieval manuscripts to today’s 3D digital models. It’s a story of curiosity overcoming taboo, of art advancing science and science perfecting art, of technology transforming how we see ourselves.

In this guide, you’ll discover how anatomical drawing evolved from schematic symbols to photorealistic precision, who the pioneering artists and physicians were that risked their reputations (and sometimes their lives) to advance anatomical knowledge, why certain cultures embraced dissection while others forbade it, and how the techniques developed centuries ago still influence medical education and figure drawing today. Whether you’re an artist seeking to understand the tradition you’re working in, a medical student curious about your discipline’s visual heritage, or simply fascinated by how humans came to understand their own bodies, this comprehensive exploration traces the complete arc of anatomical drawing from ancient times to the digital age.

What Is Anatomical Drawing? Foundations and Definitions

Before diving into millennia of history, we need to establish exactly what we mean by “anatomical drawing”—a term that encompasses more than you might initially think.

Defining Anatomical Drawing

Anatomical drawing is the practice of creating visual representations of the human body’s internal and external structures based on systematic observation. Unlike imaginative figure drawing or stylized illustration, anatomical drawing aims for scientific accuracy—showing bones, muscles, organs, and systems as they actually exist.

The key characteristics that define anatomical drawing include:

- Observational foundation: Based on direct study of actual human bodies, not imagination or stylistic convention

- Structural emphasis: Focuses on how the body is built—skeletal framework, muscular attachments, organ relationships

- Educational purpose: Created primarily to teach, document, or advance understanding

- Technical precision: Employs specific techniques (cross-hatching, multiple views, composite illustrations) to show three-dimensional structures on two-dimensional surfaces

What makes anatomical drawing unique among visual arts is that it requires death to create knowledge for the living. Every significant advance in anatomical drawing throughout history depended on access to cadavers—human bodies available for dissection and study.

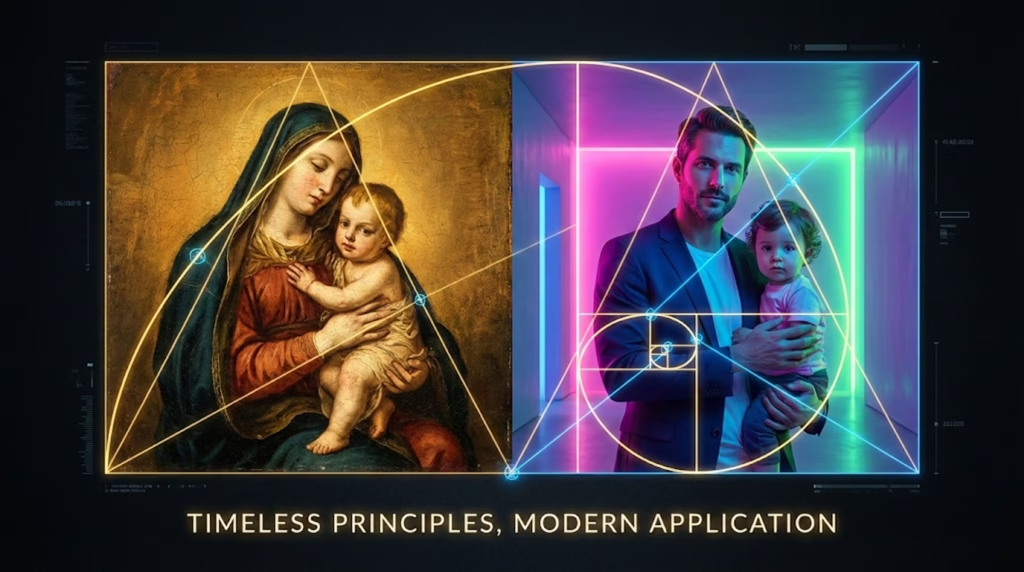

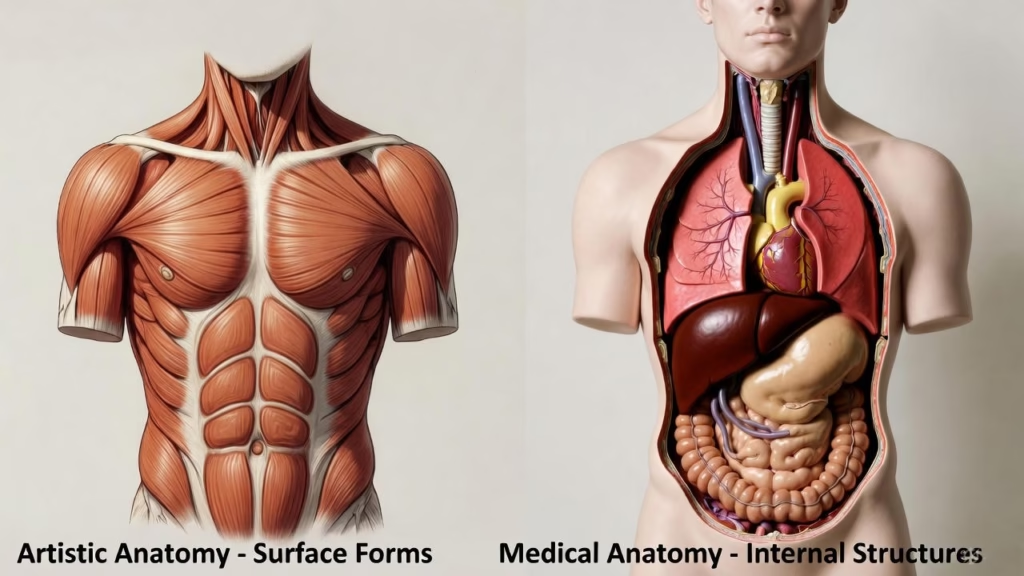

The Two Traditions: Medical and Artistic

Throughout history, anatomical drawing has developed along two parallel but interconnected paths: medical anatomy and artistic anatomy.

Medical anatomy focuses on internal structures invisible from the body’s surface. It shows the precise location of organs, the pathway of blood vessels, the connections between bones, and the layering of tissue. Medical anatomical illustration serves physicians, surgeons, and medical students who need to understand what lies beneath the skin for diagnosis, treatment, and surgical procedures. The priority here is functional accuracy—showing exactly where to find the liver, how the heart’s chambers connect, which nerves run through which passages.

Artistic anatomy concentrates on surface forms and how underlying structures create visible shapes. Artists need to understand how muscles bunch and stretch, how bones create landmarks on the skin’s surface, how the body’s proportions relate to each other. Artistic anatomical study helps painters and sculptors create convincing human figures—showing how the deltoid muscle creates the shoulder’s curve, how the scapula shows through a thin back, how the ribcage influences the torso’s shape.

The two traditions overlap significantly. Many of the most important figures in anatomical art history worked in both realms. Leonardo da Vinci dissected cadavers primarily to improve his painting but ended up making genuine medical discoveries. Frank Netter trained as a physician before becoming the 20th century’s most influential medical illustrator. The boundaries blur because both traditions share the same foundation: understanding how human bodies are actually constructed.

Why Anatomical Drawing Emerged

Human curiosity about what’s inside our bodies is ancient and universal. But three specific needs drove the development of anatomical drawing:

Medical necessity created the earliest anatomical study. Ancient physicians needed to understand internal structures to treat injuries, perform surgeries, and diagnose diseases. If you’re going to cut into a human body to remove a damaged organ or repair an injury, you’d better know what you’ll find inside and how the parts connect. Early medical texts included anatomical diagrams primarily as surgical references.

Artistic ambition fueled anatomical drawing’s Renaissance revolution. As artists pursued ever more realistic representation of the human form, surface observation alone proved insufficient. To paint a twisting torso convincingly, you need to understand how muscles layer over bones. To sculpt a raised arm accurately, you need to know which muscles are flexing and which are stretching. Renaissance artists like Leonardo and Michelangelo sought anatomical knowledge because their art demanded it.

Philosophical and religious motivations also played a role. Some cultures viewed understanding the body as understanding divine creation—a form of religious devotion. Others saw anatomical study as revealing nature’s mechanical principles. The Enlightenment’s scientific worldview made systematic anatomical documentation a matter of cataloging natural reality, part of humanity’s project to understand and classify the natural world.

But here’s what makes the history fascinating: while curiosity was constant, whether that curiosity could be satisfied depended entirely on cultural attitudes toward dissection. Throughout most of human history, cutting open dead bodies was taboo—religiously forbidden, socially unacceptable, or legally banned. The history of anatomical drawing is therefore also a history of changing attitudes toward death, the body, and the pursuit of knowledge.

Ancient Foundations: Early Anatomical Study (3000 BCE – 400 CE)

The history of anatomical drawing doesn’t begin with Renaissance masters sketching by candlelight. It starts thousands of years earlier, in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, where the first medical observers tried to document what they learned about the human body’s interior.

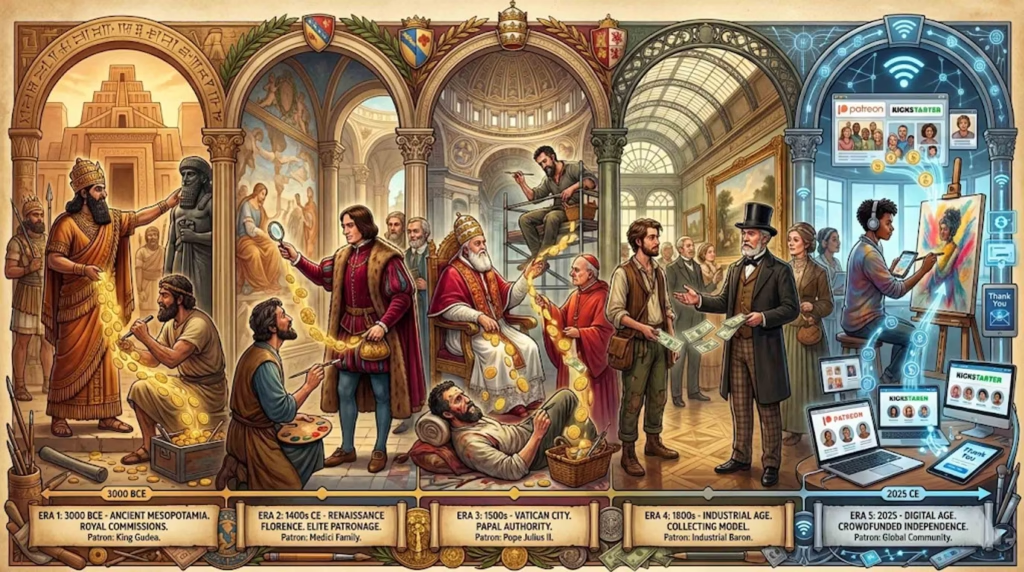

Egyptian Medical Knowledge (3000-1500 BCE)

Ancient Egypt provides our earliest evidence of medical anatomical knowledge. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, dating to around 1600 BCE but likely copied from much older texts, describes 48 surgical cases with remarkable anatomical detail. It identifies the brain, discusses skull fractures, and recognizes that the heart pumps blood through vessels.

The Ebers Papyrus, another key medical text, contains over 700 remedies and describes anatomical features relevant to treatment. Egyptian physicians clearly understood aspects of internal anatomy—they could identify organs, knew the heart was central to circulation, and recognized major blood vessels.

Yet Egyptian anatomical illustrations, when they appear at all, are surprisingly schematic and symbolic rather than realistic. Why? Despite their intimate familiarity with body interiors through mummification, Egyptians maintained a strict separation between embalming practice and medical knowledge. Mummification was a religious ritual performed by specialized priests, while medicine was a separate profession. The two didn’t share knowledge systematically.

Religious prohibitions prevented medical dissection for study purposes. The body needed to remain intact for the afterlife, so cutting it open purely to learn was unacceptable. Egyptian medical knowledge came primarily from treating wounds and from the inevitable anatomical exposure during mummification, not from systematic anatomical investigation.

What survived in Egyptian medical papyri are therefore schematic diagrams showing body regions and systems in symbolic form—more like maps than realistic drawings. These early attempts at anatomical illustration established a pattern we’ll see repeatedly: when dissection is prohibited or rare, anatomical drawings remain schematic and incomplete.

Greek Medical Pioneers (500-100 BCE)

Ancient Greece transformed anatomical study from occasional observation to systematic science. The shift began in the 5th century BCE with Hippocrates and the Hippocratic corpus—medical texts emphasizing direct observation over mythological explanation.

But the real breakthrough came in Alexandria around 300 BCE under the Ptolemaic rulers. Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos became the first physicians known to systematically dissect human cadavers for anatomical study. The Ptolemies, Greek rulers of Egypt, permitted what had been forbidden elsewhere: cutting open human bodies purely to understand them.

Herophilus made remarkable discoveries. He distinguished between arteries and veins, described the brain’s ventricles, identified the duodenum (which he named), and conducted comparative anatomy studies. Erasistratus studied the heart’s structure, distinguished between sensory and motor nerves, and theorized about blood circulation.

The tragedy is that none of their anatomical drawings survive. We know about their work only through later writers who described it. Why didn’t their illustrations endure? Several reasons: materials were perishable (drawings on papyrus or parchment deteriorate), the library of Alexandria (which likely housed their work) suffered multiple destructions, and most critically, the practice of human dissection didn’t continue after them.

By 150 BCE, human dissection had again become culturally unacceptable in the Hellenistic world. The window of systematic anatomical study closed, not to reopen for over 1,400 years.

Galen and Roman Anatomical Knowledge

Galen of Pergamon (129-216 CE) became the most influential anatomical authority for the next 1,400 years—despite never dissecting a human body.

Working in Rome, where human dissection was prohibited, Galen performed extensive dissections on animals: pigs, goats, dogs, and Barbary apes (which he considered close to human anatomy). He was a brilliant observer and made important discoveries about muscle function, the nervous system, and how blood moves through the body.

But Galen’s reliance on animal anatomy introduced significant errors when he extrapolated to humans. He described a five-lobed liver (accurate for pigs, not humans), claimed the lower jaw consisted of two bones (true in dogs, false in humans), and misunderstood several aspects of the heart’s structure and function.

These errors wouldn’t have mattered much if later generations had corrected them through renewed human dissection. But they didn’t. Instead, Galen’s texts became medical doctrine, his authority so complete that questioning him was considered nearly heretical. Medieval and early Renaissance physicians, when they occasionally performed dissections, used them to confirm Galen rather than to discover new knowledge.

Galen likely produced anatomical illustrations—he refers to them in his writings—but none survive. Later medieval copies of his works include diagrams, but these were created by manuscript copyists, not by Galen himself or based on his original drawings.

Why Ancient Anatomical Drawing Remained Limited

Despite pockets of brilliant anatomical investigation, systematic anatomical drawing couldn’t develop in the ancient world because:

Cultural and religious attitudes toward dead bodies restricted dissection to brief, exceptional periods. Most ancient cultures required bodies to remain whole for proper burial or religious purposes. The Alexandrian period’s permissiveness was a rare exception.

Lack of preservation technology meant cadavers decomposed within days. Without refrigeration or effective embalming, the window for anatomical study was narrow—a few days at most in cool weather, mere hours in heat. This prevented the repeated, careful observation necessary for detailed anatomical drawing.

Absence of printing technology meant any drawings created existed in single copies. Without a way to mass-produce and distribute anatomical illustrations, knowledge remained localized and vulnerable to loss.

Medical knowledge transmission occurred primarily through text, not images. Ancient physicians learned by reading authoritative texts (like Galen) and through apprenticeship observation, not by studying anatomical atlases. The visual tradition remained underdeveloped.

The ancient period established anatomical inquiry’s foundation—the questions to ask, the structures to identify, the systematic approach to observation. But truly comprehensive anatomical drawing would require different cultural attitudes, better preservation methods, and most critically, a technology for preserving and distributing images: the printing press.

Medieval Anatomy: Preservation and Innovation (400-1400 CE)

The thousand years following Rome’s fall are often dismissed as the “Dark Ages” for science and medicine. This label is misleading—particularly regarding the Islamic world, which made crucial advances while preserving ancient knowledge that might otherwise have been lost.

Islamic Golden Age Contributions (800-1400)

While European medicine stagnated, Islamic scholars made the medieval period’s most significant anatomical advances. The Islamic Golden Age (roughly 800-1400 CE) saw the translation of Greek medical texts into Arabic, extensive commentary on those texts, and important original discoveries.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037) wrote the Canon of Medicine, which became the standard medical textbook across the Islamic world and later in Europe. His work systematized anatomical knowledge, though like Galen, he relied more on ancient texts than on personal dissection.

More significantly, Ibn al-Nafis (1213-1288) made a revolutionary anatomical discovery through logical deduction rather than dissection. In his commentary on Avicenna’s anatomy, he described pulmonary circulation—blood flowing from the right heart chamber through the lungs to the left chamber—contradicting Galen’s theory that blood passed directly through the heart’s septum. This discovery, made in 1242, wouldn’t be rediscovered in Europe for another 300 years.

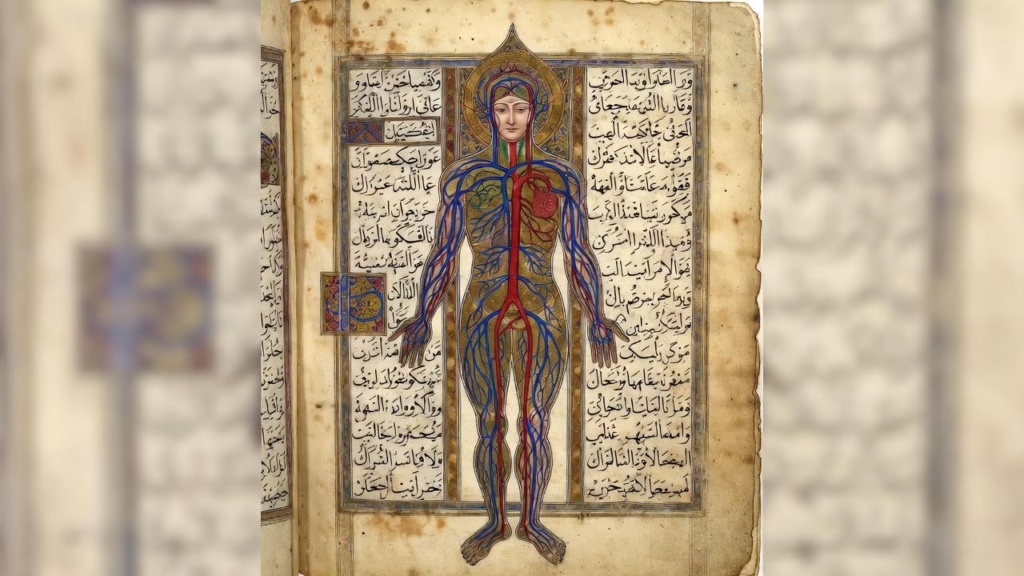

The most important anatomical illustrations of the medieval period came from Persian physician Mansur ibn Ilyas. His Tashrih-i badan-i insan (Anatomy of the Human Body), completed in 1396, contains the earliest surviving comprehensive illustrated anatomy. The manuscript includes full-color diagrams showing five body systems: skeletal, nervous, muscular, circulatory, and venous.

These illustrations are revolutionary not for realism—they remain schematic and stylized—but for systematic organization. Mansur presents the body as interconnected systems, each shown in a separate full-body diagram with clear labels. This systematic approach established a framework that Renaissance anatomists would later adopt and refine.

Islamic anatomical study faced fewer religious restrictions than contemporary European medicine. Islamic scholars could dissect animals freely, and while human dissection remained controversial, it occurred more frequently than in medieval Christian Europe. Some scholars argue that Islamic medicine’s greater openness to investigation contributed to its superior anatomical knowledge during this period.

European Medieval Anatomical Study

Medieval European anatomy was considerably more limited. The Catholic Church didn’t officially ban dissection—that’s a persistent myth—but strong cultural taboos and respect for bodily resurrection made dissection rare and controversial.

Medical education centered on reading Galen, Hippocrates, and increasingly (after Arabic texts were translated to Latin in the 12th-13th centuries), Ibn Sina. Physicians learned anatomy from books, not bodies.

When dissections occurred, they followed a rigid format. An elevated professor read from Galen’s text while a barber-surgeon performed the actual cutting, and a demonstrator pointed out structures with a stick. The purpose was to illustrate Galen’s teachings, not to discover new information. If what the demonstrator saw didn’t match Galen’s description, it was the body that was considered unusual, not Galen who was wrong.

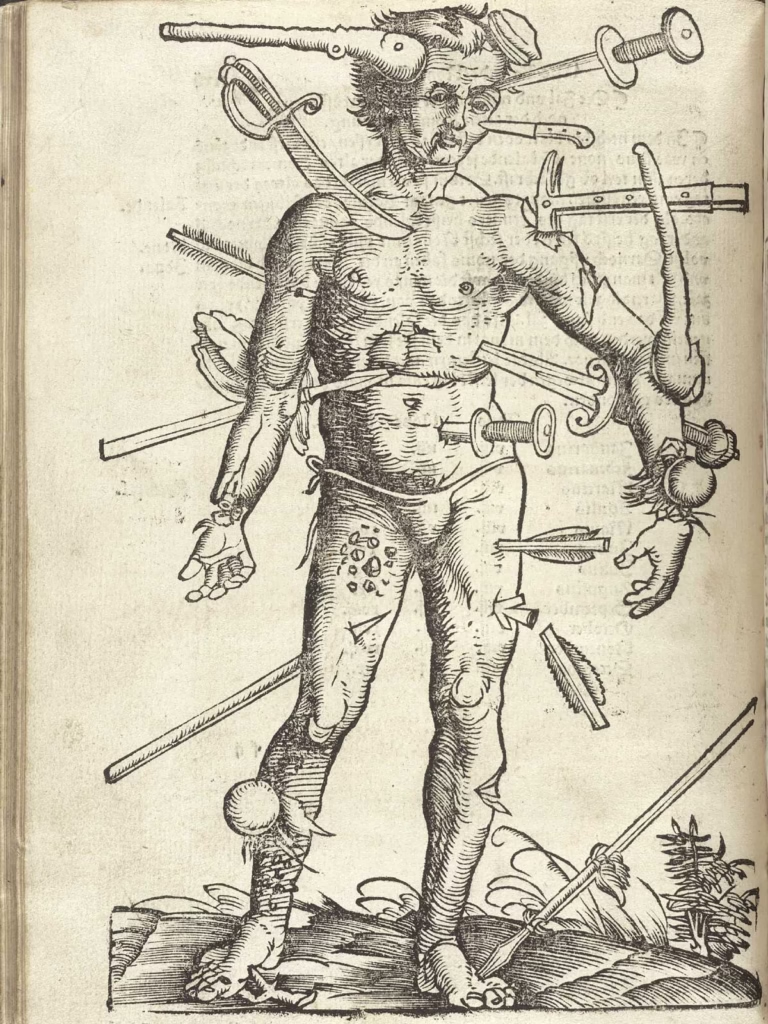

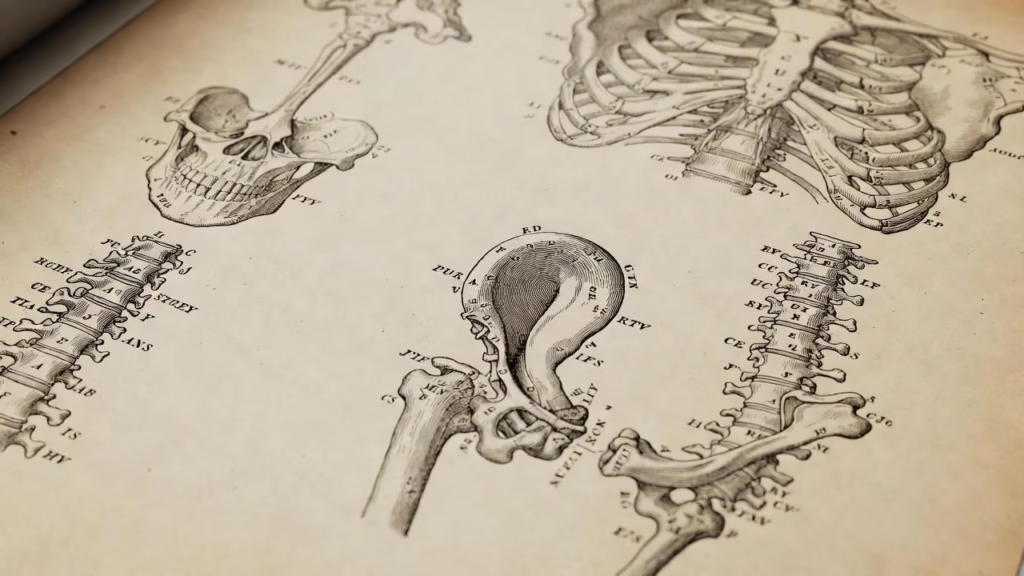

Medieval European anatomical illustrations reflect this text-based approach. Two types dominated:

Wound Man diagrams showed a human figure covered with various injuries—sword cuts, arrows, bites, breaks—with annotations about treatment. These were practical references for barber-surgeons treating traumatic injuries, essentially a visual index to wound management.

Zodiac Man (or “Homo Signorum”) diagrams connected body parts to astrological signs, reflecting medieval medical astrology’s belief that celestial influences affected health and that certain treatments should be timed according to planetary positions.

Both diagram types were schematic rather than realistic. The figures were symbolic representations, often barely resembling actual human proportions. The emphasis was on mapping information onto a human-shaped diagram, not on accurate anatomical illustration.

Mondino de Luzzi’s Anothomia (1316), the first true dissection manual written in Europe since ancient times, marked a significant advance. Mondino performed and described dissections systematically, establishing procedures that would be followed for centuries. Yet even Mondino worked primarily within Galenic tradition, interpreting what he saw through the lens of ancient authority.

Manuscript Illumination and Medical Texts

Medieval anatomical illustrations, when they existed, were hand-drawn in manuscript copies. Each time a medical text was copied—the only way to “publish” before printing—its illustrations were also hand-copied.

This process had inevitable consequences. Copyists, usually monks without medical training, didn’t understand what they were drawing. Mistakes crept in with each generation of copying. A structure might be drawn slightly wrong, then more wrong in the next copy, until it barely resembled the original.

Illustrations in medieval medical manuscripts are often strikingly beautiful, showing the extraordinary skill of manuscript illuminators. Rich colors, intricate borders, and elegant lettering make these texts works of art. But their anatomical accuracy is questionable. The same artistic conventions used in religious manuscripts—stylized figures, symbolic colors, flat perspectives—appeared in anatomical illustrations.

The limitations weren’t just technical but conceptual. Medieval illustrators didn’t distinguish sharply between literal and symbolic representation. A diagram showing the body’s “humors” (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile) might depict these as colored regions within a body outline—not because anyone believed you’d see four-colored zones if you cut a body open, but because the diagram’s purpose was to explain a theory, not to show actual anatomy.

This medieval period established a crucial pattern: anatomical illustration cannot advance without direct observational study. No amount of artistic skill or beautiful manuscript illumination could substitute for systematic dissection. The knowledge gap between Islamic and European medieval anatomy correlates directly with greater Islamic openness to anatomical investigation.

The Renaissance Revolution (1400-1600)

Everything changed in 15th-century Europe. The Renaissance brought a perfect storm of conditions that revolutionized anatomical drawing: renewed emphasis on direct observation over ancient authority, improved access to cadavers, artistic humanism’s drive for realistic representation, and crucially, the printing press’s ability to preserve and distribute images.

Why the Renaissance Changed Everything

Several interconnected factors made the Renaissance anatomical revolution possible:

Cultural attitudes shifted toward empirical observation. Renaissance humanism valued direct engagement with nature over pure reliance on ancient texts. “See for yourself” became a valid approach, even regarding topics—like what’s inside human bodies—that had been the exclusive domain of textual authority.

Artistic humanism created new motivation for anatomical study. Renaissance artists pursued unprecedented realism in painting and sculpture. Mastering human form required understanding its underlying structure. Artists became some of the period’s most motivated anatomical students.

Access to cadavers improved, particularly in Italy. Universities in Padua, Bologna, and other cities established regular public dissections. Bodies of executed criminals became available for anatomical study. While still limited, opportunities for dissection increased dramatically compared to medieval Europe.

The printing press (invented around 1450) transformed everything. For the first time, anatomical illustrations could be mass-produced with consistent quality. An accurate anatomical drawing in a printed book could reach thousands of readers in identical form. This made comprehensive anatomical illustration worthwhile—you weren’t creating a single manuscript that might get copied incorrectly, but producing woodcuts or engravings that would distribute knowledge widely.

These factors converged to make detailed, observation-based anatomical drawing not just possible but highly desirable. And into this fertile environment stepped some of history’s greatest anatomical artists.

Leonardo da Vinci: The Anatomist-Artist (1480s-1519)

Leonardo da Vinci dissected approximately 30 human cadavers between the 1480s and his death in 1519, creating over 240 anatomical drawings that rank among humanity’s greatest achievements in both art and science.

Leonardo came to anatomy as an artist seeking to perfect his painting. If you look at his notebooks chronologically, you see the shift from artistic surface anatomy (what creates visible form) to genuine scientific curiosity about how the body functions mechanically. By the 1500s, Leonardo was planning a comprehensive anatomical treatise—not primarily for artists, but as a fundamental work of science.

What made Leonardo’s anatomical drawings revolutionary?

His observational rigor went far beyond anything previous. He didn’t dissect a single body and consider his knowledge complete. He dissected repeatedly, comparing specimens, returning to verify observations, correcting his own earlier mistakes. His drawings show this iterative process—initial sketches, more detailed studies, annotations noting differences between bodies.

His technical innovations transformed anatomical illustration. Leonardo pioneered cross-hatching—using closely-spaced parallel lines crossed at angles to build up volume and shadow. His cross-hatching could be extraordinarily fine, with lines spaced as little as 0.5mm apart, creating subtle gradations that showed three-dimensional form on flat paper. He drew the same structure from multiple angles, giving 360-degree views. He created “exploded” views showing how parts relate spatially, separating layers to reveal deeper structures. He drew transparent views, showing bones through muscles or organs within the body cavity.

His discoveries were genuinely original. Leonardo accurately documented the heart’s structure, correcting Galenic errors about its chambers. He studied the eye’s optics with unprecedented sophistication. His drawings of the fetus in the womb, based on dissection of a pregnant woman who died, showed details not seen again for centuries. His studies of facial muscles helped him understand expression—useful for painting but also scientifically significant.

His comparative anatomy approach was centuries ahead of its time. Leonardo dissected animals alongside humans, comparing structures, seeking general principles. He drew analogies between human anatomy and mechanical systems—treating the arm as a lever system, for instance, anticipating biomechanics by 400 years.

Yet Leonardo’s anatomical work had a tragic limitation: he never published it. The notebooks remained private, passing after his death to his assistant Francesco Melzi, then to Melzi’s son, gradually dispersing. They weren’t systematically published until the early 20th century. So while Leonardo’s anatomical drawings are extraordinary, they had virtually no influence on anatomical science’s development. The anatomical revolution of the 1500s happened independently of Leonardo’s work.

Leonardo’s anatomical drawings survive at Windsor Castle’s Royal Library today—240 sheets of extraordinary observation, technical brilliance, and scientific insight that history forgot for 400 years.

Andreas Vesalius and the Revolution in Print (1543)

If Leonardo was anatomical drawing’s greatest practitioner whose work changed nothing because no one saw it, Andreas Vesalius was the revolutionary whose work changed everything because everyone could see it.

Vesalius (1514-1564) was a young Flemish physician teaching anatomy at the University of Padua when he produced De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) in 1543. At age 28, he published what immediately became the most important anatomical atlas ever created.

What made the Fabrica revolutionary wasn’t just its content—systematic, comprehensive coverage of human anatomy based on direct observation—but its production. Vesalius collaborated with artists, probably from Titian’s workshop in Venice, possibly including Jan Stephen van Calcar. Together they created over 200 large-format woodcut illustrations of unprecedented quality and detail.

The Fabrica‘s illustrations established principles still followed in anatomical illustration today:

Systematic progression from surface to depth. The famous muscle men sequence shows the same figure progressively dissected—first layer, second layer, deeper structures—allowing readers to understand how muscles layer over each other and over bones.

Multiple views of the same structure from different angles. Bones shown from front, back, side, allowing three-dimensional understanding from two-dimensional images.

Contextual settings making the illustrations aesthetically engaging while serving scientific purposes. The muscle men stand in landscape backgrounds, posed dramatically. This wasn’t mere decoration—the poses showed how muscles function in different positions.

Accurate proportions and relationships. Unlike schematic diagrams, these images showed true anatomical proportions, helping readers understand spatial relationships between structures.

Clear labeling keyed to detailed text. Letters marked structures, referenced in Vesalius’s descriptions, creating an integrated image-text system.

Vesalius explicitly challenged Galenic anatomy, pointing out over 200 errors in Galen’s work. He could do this because he had performed extensive human dissections—publicly, at Padua’s anatomy theater, where his demonstrations drew huge crowds.

The Fabrica was immediately controversial. Some physicians attacked Vesalius for contradicting Galen. But the evidence was there in the illustrations—anyone with access to a cadaver could verify that Vesalius was right and Galen wrong on numerous specific points. Within a generation, the Fabrica had largely displaced Galenic anatomy as the anatomical authority.

The printing press made this possible. The Fabrica‘s first edition (1543) was printed in Basel in hundreds of copies with identical illustrations. A second, revised edition followed in 1555. Copies spread across Europe. Pirates produced unauthorized editions. By 1600, Vesalius’s anatomical illustrations had become the foundation of anatomical knowledge across the Western world.

This was the true anatomical revolution: not just better observation (Leonardo had that), but observation captured in reproducible images, distributed widely, establishing a new visual standard for anatomical truth.

Anatomical Theaters and Public Spectacle

The physical spaces where Renaissance dissections occurred reveal much about anatomy’s cultural status.

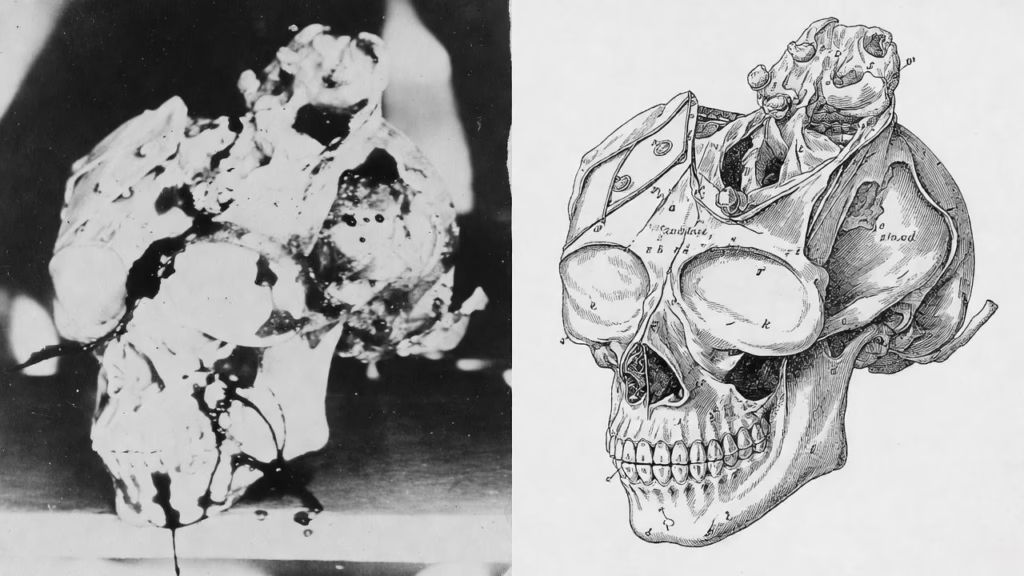

The first permanent anatomical theater was built at the University of Padua in 1594, followed quickly by Leiden (1597) and others across Europe. Their architecture was highly theatrical: steep circular tiers of wooden benches rising around a central dissection table, maximizing the number of observers who could see the demonstration while providing clear sightlines.

But “theater” is apt for another reason—these were public spectacles, not just medical education. Dissections were scheduled in winter when cold weather slowed decomposition and announced publicly weeks in advance. Medical students attended, yes, but so did artists, philosophers, wealthy citizens, even tourists. Admission might be charged. The atmosphere combined serious learning with entertainment.

Public dissections typically followed a specific sequence over three to four days:

Day 1: The abdominal cavity, which decomposed fastest, was opened first. The anatomist would identify and explain the stomach, liver, intestines, kidneys, and other organs visible in this region.

Day 2: The thorax was opened, showing the heart, lungs, and great vessels. This was often considered the most significant part, as the heart’s structure was central to medical theory.

Day 3: The head was opened, revealing the brain. This completed the “noble” organs.

Day 4: If the body remained usable, extremities and remaining structures were demonstrated.

Artists attended these public dissections in significant numbers. Academic art training increasingly emphasized anatomical knowledge, and the winter dissection season offered artists rare opportunities to observe internal structures. They would sketch quickly during the demonstration, then work from memory and notes later to create more finished anatomical drawings.

The anatomical theater’s architecture and ritual had important effects. First, it normalized human dissection. What had been controversial became routine—an expected part of a university city’s cultural calendar. Second, it created a market for anatomical knowledge. People who couldn’t attend dissections wanted anatomical books and prints. This economic incentive supported the development of anatomical illustration as a profession.

Other Key Renaissance Figures

While Leonardo and Vesalius dominate Renaissance anatomical history, other important figures advanced the field:

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) approached anatomy from a pure artist’s perspective with his Four Books on Human Proportion (published posthumously in 1528). Dürer’s work wasn’t about internal anatomy but about mathematical systems for depicting human form. He measured and systematized body proportions, showing not just an ideal but variations—different body types, ages, and builds. This mathematical approach influenced figure drawing instruction for centuries and established proportion study as fundamental to artistic anatomy.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) conducted dissections, though less systematically than Leonardo. His anatomical knowledge is evident in his sculptures and painting—the Sistine Chapel ceiling figures show sophisticated understanding of how muscles create form, how the skeleton determines posture. Michelangelo’s approach was pragmatic: he studied anatomy to make his art more convincing, then applied that knowledge immediately to his work.

Bartolomeo Eustachi (1514-1574) created anatomical plates between 1552-1564 that rivaled Vesalius’s work in quality. Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae showed exquisite detail, particularly of the nervous system, kidneys, and larynx. Through various mishaps, his plates weren’t published until 1714—over 150 years after creation—but when finally printed, they influenced 18th-century anatomy.

Fabricius ab Aquapendente (1533-1619), who studied under Vesalius’s successors at Padua, made important embryological studies and designed the Padua anatomical theater. His illustrated works on embryology and comparative anatomy extended anatomical illustration beyond adult human anatomy.

The Renaissance established observation-based anatomical drawing as both art and science. It created the basic techniques—systematic dissection, progressive revelation, multiple views, clear illustration—that would be refined but not fundamentally changed for the next 400 years.

The Baroque Period: Refinement and Systematization (1600-1750)

After the Renaissance breakthrough, the 17th and 18th centuries refined and systematized anatomical knowledge. Dissection became routine in medical education. Anatomical illustration became a recognized profession. And most significantly, anatomy was formalized as essential training for artists.

Academic Art Education and Anatomy

The French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture), founded in 1648, established the model that would dominate art education for the next 250 years. Anatomical study became required curriculum.

The Academy’s progression was systematic: students began drawing from prints and drawings (copying master works), advanced to drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures, then progressed to drawing from écorché (flayed) sculptures showing muscular anatomy, and finally were permitted to draw from live nude models.

This sequence ensured that by the time students drew living models, they understood the anatomical structures beneath the skin. The live model’s surface forms made sense because students already knew the muscles and bones creating those forms.

Anatomy lectures and demonstrations became standard features of European art academies. A physician or anatomist would lecture, often accompanied by dissection demonstrations. Students were expected to attend dissections and create anatomical studies as part of their training.

This formalization had profound effects. It established anatomical knowledge as fundamental to artistic competence—you couldn’t be considered a serious figure painter or sculptor without it. It created consistent teaching methods. And it normalized the idea that artists needed access to cadaver dissection, making that access more readily available.

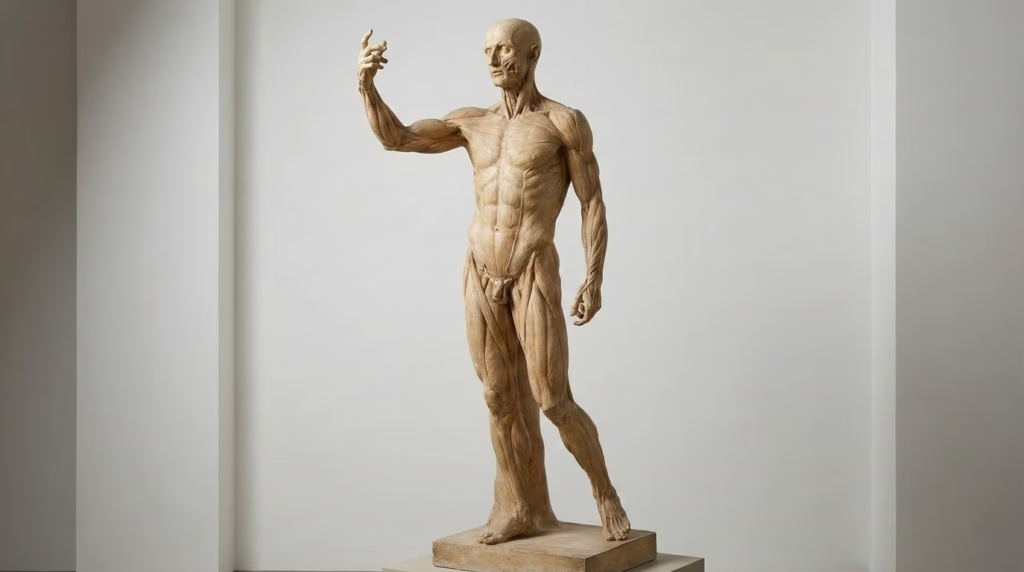

Écorché Sculptures and Drawing Aids

One of the period’s most important developments was the écorché sculpture—life-size figures showing the muscular system without skin, used as permanent anatomical references.

The most famous is Houdon’s Écorché (1767), created by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. This life-size standing figure shows every muscle with extraordinary accuracy and remains in use today for art instruction. The figure stands in a dramatic pose (one arm raised, body twisting), demonstrating how muscles function in action, not just in relaxed positions.

Écorché sculptures solved several problems. They provided permanent three-dimensional anatomical references, eliminating the need for constant cadaver access. They showed idealized, composite anatomy—not one specific body but a systematized representation of general muscular structure. They could be studied from any angle, in any lighting, for as long as needed.

Students would spend months drawing the écorché from different viewpoints, in different lighting conditions, until they had thoroughly internalized muscular anatomy. Only then would they progress to drawing living models, applying their anatomical knowledge to understanding how muscles create the surface forms they saw.

This pedagogical approach—écorché before live model—remained standard in classical art training into the 20th century and is still practiced in some contemporary ateliers.

Dutch Anatomical Innovation

The Dutch Republic, Europe’s most prosperous region in the 17th century, made important contributions to anatomical art.

Amsterdam’s public dissections became civic occasions. Rembrandt’s famous painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) captures this: a group portrait of the surgeons’ guild members gathered around a dissection. While primarily a commissioned portrait, it shows anatomy’s status—important enough to be the subject of a major painting hung in the guild hall.

Dutch prosperity supported anatomical innovation in another way: wealthy citizens would commission anatomical preparations as displays of scientific curiosity and civic pride. This created demand for skilled anatomical preparers and illustrators.

Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731) perfected anatomical preservation techniques, creating preparations that could last for years. His preserved specimens became famous across Europe, and visitors to Amsterdam would tour his collection. Ruysch developed secret methods for arterial injection that kept tissue color and texture natural-looking rather than degraded.

Govert Bidloo’s Anatomia humani corporis (1685) featured extraordinary copper engravings that surpassed earlier woodcuts in detail and subtlety. The sharper lines possible with copper engraving allowed finer detail—individual muscle fibers, small vessels, delicate tissues all rendered with new clarity.

Advances in Illustration Technology

The shift from woodcut to copper engraving represented a significant technological advance.

Woodcut (used by Vesalius) involved carving away wood, leaving raised lines that would take ink. The technique was durable—woodblocks could produce thousands of prints—but had limitations in fine detail. Very thin lines were fragile and might break.

Copper engraving involved incising lines into metal plates. The engraver could create much finer, more controlled lines. Subtle gradations through dense cross-hatching became possible. The result was illustrations with unprecedented detail and tonal range.

Etching, where acid etches lines into metal, offered even more flexibility. The etcher could work more fluidly, creating varied line quality—thick and thin, dense and sparse—in ways engraving’s mechanical process made difficult.

These technological improvements weren’t merely aesthetic. They enabled more accurate anatomical illustration. Finer lines meant smaller structures—tiny blood vessels, nerve branches, delicate organ textures—could be shown clearly. Better tonal range meant three-dimensional form could be rendered more convincingly.

Hand-tinting of prints added another dimension. While the printing was black and white, colorists would hand-paint individual prints, adding color to distinguish different structures—arteries red, veins blue, nerves yellow. A single engraved plate could thus produce both uncolored anatomical prints (cheaper) and hand-colored versions (more expensive but more informative).

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus: The Pursuit of Perfection

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770), a German anatomist working in Leiden, took anatomical illustration to new heights of accuracy with his Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani (Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles of the Human Body, 1747).

Albinus collaborated with engraver Jan Wandelaar to develop a revolutionary methodology. They used a camera obscura—an optical device projecting images—along with a precisely calibrated grid system to ensure accurate proportions. The specimen and the drawing were positioned in exact spatial relationships, with measurements taken and cross-referenced, eliminating the distortions that could creep in with freehand drawing.

The result was unprecedented accuracy. Albinus’s skeletal and muscular figures showed not just approximately correct proportions but precisely measured relationships. Every dimension could be verified against the original specimens.

The famous image of a skeleton with a rhinoceros in the background wasn’t mere decoration. Albinus used exotic animals as background elements partly for aesthetic interest, but also to demonstrate his technique’s versatility—if he could accurately render both human skeleton and rhinoceros from life, it proved his systematic approach.

Albinus’s work set a new standard for anatomical illustration. His pursuit of measured accuracy through mechanical aids anticipated later developments in anatomical photography and medical imaging. The idea that anatomical illustration should be not just skillful but precisely verifiable became increasingly important.

The Enlightenment and Medical Illustration (1750-1850)

The Enlightenment brought systematic classification to natural history, professionalization to medicine, and increasing specialization to anatomical illustration. Surgery gained respectability, creating demand for surgical atlases. Medical illustration emerged as a distinct profession, separate from both fine art and medical practice.

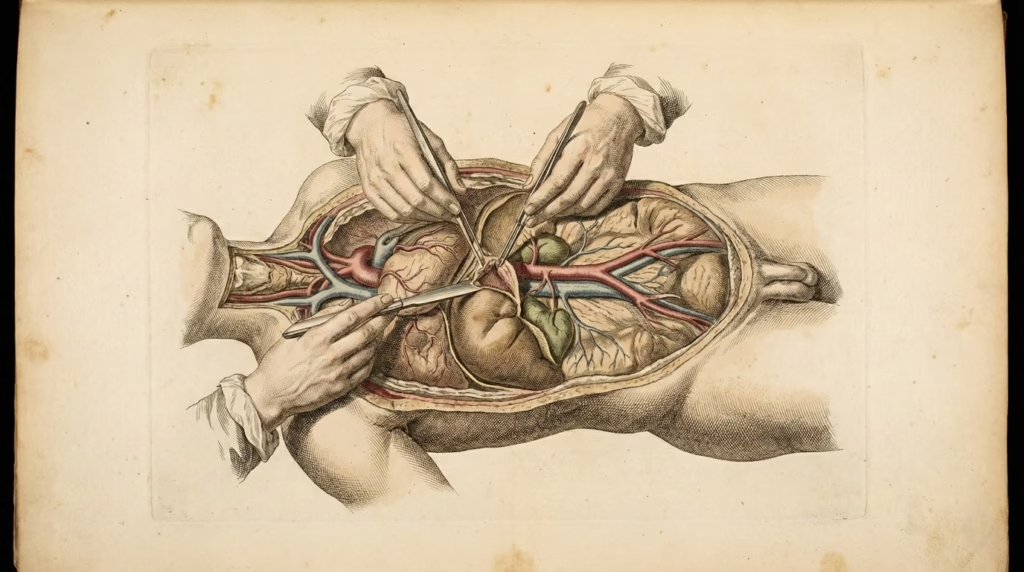

The Age of Surgical Atlases

As surgery evolved from barber-surgeons’ crude interventions to a respected medical specialty, surgeons needed detailed visual guides. Surgical atlases proliferated—step-by-step illustrated procedures showing exactly where to cut, what structures would be encountered, how to navigate anatomical complexities.

Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty created the first anatomical prints in full color using color mezzotint, a complex printing technique involving multiple plates. His Anatomie des parties de la génération (1745-1773) and other works used color not decoratively but informationally—different tissues in different colors, making complex relationships clearer. The technique was expensive and technically challenging, limiting its use, but it demonstrated color’s value in anatomical illustration.

William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) represented both scientific advance and social controversy. Hunter, a Scottish physician, documented pregnancy anatomy with unprecedented detail through Jan van Rymsdyk’s superb illustrations. The work showed 34 copper plates depicting pregnancy at different stages, the uterus and fetus in various positions, and anatomical details of female reproductive anatomy.

This was controversial. Depicting female reproductive anatomy was considered indelicate, if not obscene, in 18th-century society. That Hunter’s atlas depicted dead women’s opened bodies made it more troubling. But the scientific value was undeniable—obstetrics desperately needed better anatomical understanding to reduce maternal mortality. Hunter’s atlas became essential reference for obstetricians despite social discomfort.

Medical Illustration as Profession

During this period, medical illustration became a recognized specialty with its own training pathways and professional identity.

Medical illustrators weren’t physicians—they lacked medical training and didn’t practice medicine. They weren’t fine artists in the traditional sense—they weren’t painting allegories or portraits for wealthy patrons. They were specialists whose skills combined artistic technique, anatomical knowledge, and the ability to communicate visually with physicians and students.

Training typically occurred through apprenticeship. A young artist with aptitude would study under an established medical illustrator, learning both drawing techniques and anatomical knowledge. They’d attend dissections, study from specimens, practice rendering different tissues and structures, and learn how to translate three-dimensional anatomy into two-dimensional illustrations that clearly communicated medical information.

Skills required were specific: precise line work, subtle shading to show depth and texture, ability to work from specimens under time pressure (before decomposition), understanding of what medical audiences needed to see (not necessarily what looked artistically interesting), and collaboration skills to work effectively with physician-anatomists.

The economics supported specialization. Medical textbooks, surgical atlases, and individual anatomical prints created steady demand. Publishers needed reliable illustrators who could work quickly and accurately. This professionalization meant quality improved—specialists became very skilled at their specific craft—but also meant medical illustration diverged somewhat from fine art.

Anatomical Wax Modeling

An alternative to drawn anatomical illustration emerged: wax anatomical models.

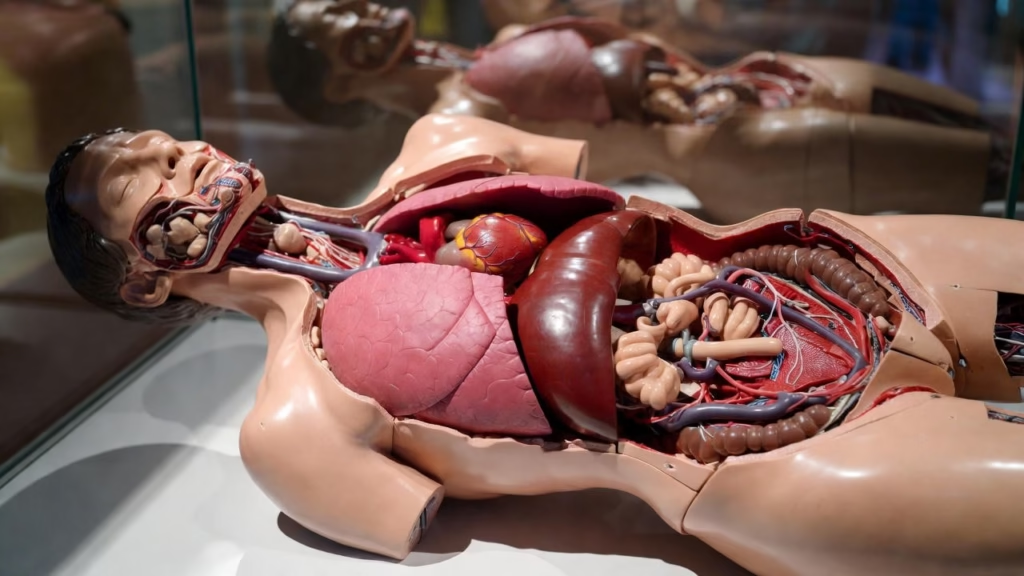

Clemente Susini (1754-1814) in Florence created extraordinary wax anatomies for the La Specola museum. These life-size figures showed internal anatomy with startling realism—accurate colors, textures approximating real tissue, layered construction allowing progressive revelation.

Wax modeling offered advantages over drawings: three-dimensionality (you could walk around them, seeing anatomy from any angle), long-term durability (a well-made wax model could last indefinitely), and tactile presence (the physical reality of a life-size anatomical figure made a powerful impression).

Anna Morandi Manzolini (1714-1774) deserves special mention as one of very few women in anatomical art history. She was a skilled wax modeler and anatomist in Bologna who created numerous anatomical wax preparations, taught anatomy, and even performed dissections—all remarkable for a woman in the 18th century. Her work demonstrated that anatomical science wasn’t inherently masculine; the field excluded women through social barriers, not natural inability.

The most famous wax anatomies are the “Anatomical Venuses”—reclining female figures that could be progressively disassembled, revealing layer after layer of internal anatomy. These figures combined scientific function with aesthetic appeal (or disturbing eroticism, depending on perspective). Styled as beautiful sleeping women but shown with opened torsos displaying organs, they occupied an uncomfortable space between scientific specimen and art object.

Wax anatomies served similar purposes to anatomical illustration—medical education, public demonstration of anatomical knowledge—but reached different audiences and served different needs. They were expensive and difficult to produce, limiting their number, but those that were created became treasured possessions of medical schools and museums.

Expansion Beyond Europe

Anatomical knowledge and illustration gradually spread globally, though remaining centered in Europe and North America.

Medical schools in Philadelphia and Boston, established in the late 18th century, adopted European anatomical education models, including anatomical illustration and dissection-based teaching. American physicians studied in Europe, then brought current anatomical knowledge and teaching methods home.

In Japan, the Kaitai Shinsho (New Book of Anatomy, 1774) translated a Dutch anatomical text into Japanese. This was significant because it introduced Western anatomical knowledge, based on human dissection, to a culture whose own anatomical understanding had been limited by restrictions on dissection. The translation sparked Japanese interest in Western medical knowledge (Rangaku, Dutch learning), gradually opening Japanese medicine to European anatomical science.

Chinese traditional medicine, with its own elaborate anatomical theories based on energy systems rather than structural anatomy, remained largely separate from Western anatomical tradition through this period. Acupuncture charts and medical illustrations in the Chinese tradition showed meridians and energy flows, not muscles and organs in the Western sense.

This cultural variation highlights an important point: anatomical drawing as we’ve been discussing it is a specifically Western tradition, emerging from Greek medicine, Islamic preservation, and European Renaissance observation. Other cultures had their own medical systems and visual representations of the body, different but not necessarily inferior, serving their medical paradigms.

The Modern Era: Gray’s Anatomy and Beyond (1850-1950)

The century from 1850 to 1950 saw anatomical illustration reach its classical peak with Gray’s Anatomy while simultaneously facing challenges from photography. It witnessed the professionalization of medical illustration as a distinct career, the introduction of color printing, and ultimately the coexistence of traditional illustration with new imaging technologies.

Henry Gray and Henry Vandyke Carter

When Gray’s Anatomy was first published in 1858 under the full title Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical, it immediately became the standard anatomical reference for English-speaking medical students. It remains in print today, now in its 42nd edition, still called Gray’s Anatomy though Gray himself died in 1861.

But there’s an injustice in that name. Henry Gray (1827-1861) was a surgeon who wrote the text, but Henry Vandyke Carter (1831-1897) created all 363 illustrations for the first edition. Carter was both a skilled anatomist and an accomplished artist. He performed the dissections, made the observations, and created the drawings. Yet his name rarely appears in discussions of the book.

Carter received £150 for his work—a flat fee, no royalties—while Gray negotiated ownership and royalty rights. After the first edition’s success, Gray controlled subsequent editions until his early death from smallpox. Carter, meanwhile, went to India as an army surgeon and had a distinguished but separate medical career.

What made Carter’s illustrations revolutionary was their clarity and functionality. Unlike earlier anatomical illustrations that often emphasized aesthetic qualities—dramatic poses, landscape backgrounds, artistic flourishes—Carter’s drawings were stripped-down and focused. Every line served an explanatory purpose. Labels were clear and numerous. Multiple views showed structures from different angles. Complex anatomies were shown in both overview and detailed close-ups.

The style was intentionally simplified compared to elaborate copper engravings of previous generations. Carter used clear outlines and minimal shading, making structures easy to identify. This made the illustrations better teaching tools, even if perhaps less impressive as artworks.

Gray’s Anatomy‘s success established this functional, clarity-focused approach as the standard for medical illustration. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, anatomical atlases followed Carter’s model: clear, well-labeled, pedagogically organized illustrations prioritizing educational value over artistic impression.

Photography’s Impact on Anatomical Illustration

The invention of photography in the 1840s raised an obvious question: if you can photograph anatomical specimens, why draw them?

Early anatomical photographs appeared in the 1850s-60s. They showed real specimens with camera-guaranteed accuracy. No risk of illustrator error or artistic interpretation. Photography seemed poised to replace anatomical drawing entirely.

It didn’t happen. Anatomical illustration remained essential because photography, despite its objectivity, had serious limitations for anatomical teaching:

Photographs show everything, including irrelevant details—blood, damaged tissue, individual variations, artifacts of decomposition. Illustrations can selectively emphasize relevant structures while minimizing distracting elements.

Photographs show one specimen, with all its individual quirks. Illustrations can show idealized, composite anatomy—representing general human anatomy, not one particular body’s variations.

Photographs lack three-dimensional clarity in complex areas. Two-dimensional photos of three-dimensional structures can be confusing. Skilled illustrators can use techniques—strategic cross-sectioning, transparent overlays, exploded views—to clarify spatial relationships.

Early photographs were black and white and often lacked contrast in areas where different tissues had similar tones. Hand-drawn illustrations could use color, shading, and artistic techniques to distinguish adjacent structures clearly.

The solution became hybrid: use photography as reference and verification while creating illustrations as the primary teaching tool. Anatomists would photograph specimens, then work with illustrators who would study both specimen and photographs to create final anatomical illustrations. This combined photography’s objectivity with illustration’s clarity.

By the early 20th century, anatomical illustration and anatomical photography had settled into complementary rather than competitive roles. Photographs documented specific cases, pathological conditions, surgical procedures—situations where “this exact specimen” was important. Illustrations explained general anatomy, normal structure, spatial relationships—situations where clarity and generalization served learning better than photographic specificity.

Chromolithography and Color Printing

Throughout the 19th century, most anatomical illustrations were black and white, sometimes hand-colored. Chromolithography—multi-stone color printing—changed this.

The technique, invented in the 1830s and refined through the century, used multiple lithographic stones (or later, metal plates), each printing one color. A sophisticated chromolithograph might use ten or more colors, each applied in precise registration, building up a full-color image.

For anatomical illustration, color was transformative. Different tissues could be distinguished at a glance: arteries red, veins blue, nerves yellow, different organ systems in different hues. Complex anatomies that were confusing in black and white became clear when color distinguished overlapping structures.

Johannes Sobotta’s anatomical atlases (first published 1904) exemplified chromolithographic anatomical illustration at its peak. Sobotta’s multi-volume atlases featured large-format color plates with extraordinary detail and subtle color gradations. These weren’t crude four-color printing but sophisticated chromolithographs using many colors to achieve both accuracy and aesthetic beauty.

The production was expensive and time-consuming. Each color required separate preparation and printing. Precise registration was essential—colors printed even slightly out of alignment would blur the image. But the results justified the effort. Sobotta’s atlases became standard references, prized for their color plates that made anatomy comprehensible in ways black-and-white illustrations never could.

By the 1920s-30s, color had become standard in high-quality anatomical atlases, though black-and-white illustrations continued in less expensive textbooks and teaching materials.

Art Deco and Modernist Anatomical Illustration

An unexpected development came from Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), a German physician who created anatomical illustrations using industrial and mechanical metaphors.

His most famous work, Das Leben des Menschen (The Life of Man, 1920s), depicted the body as a factory, with tiny workers operating machinery representing bodily functions. The heart became a pumping station, digestion an industrial processing plant, the nervous system a telephone switchboard.

This wasn’t just creative illustration—it reflected modernist aesthetics and the machine age’s influence. Kahn made anatomy accessible to general audiences by using familiar industrial imagery to explain unfamiliar biological processes. His style was graphically bold, using simplified forms and flat colors that reflected Art Deco and modernist design.

While Kahn’s approach wasn’t adopted for traditional medical education (students needed anatomical accuracy, not metaphorical interpretation), it influenced medical illustration for public health education and popular science. The realization that anatomical illustration could be stylized, metaphorical, and accessible—not just technically accurate—opened new possibilities for visual medical communication.

Academic Figure Drawing Continues

Despite modernism’s rise in fine art, academic figure drawing based on anatomical study continued throughout this period and beyond.

Artists like George Bridgman (1865-1943), Andrew Loomis (1892-1959), and Burne Hogarth (1911-1996) published anatomy-for-artists books that remained influential throughout the 20th century. These weren’t medical anatomy texts but artist-focused guides showing how anatomical structure creates surface form.

Art schools, even as they embraced modern and abstract movements, typically maintained life drawing classes where students learned figure drawing grounded in anatomical understanding. The classical curriculum—écorché study before live model—persisted in some traditional ateliers.

This created an interesting split: fine art increasingly valued abstraction and moved away from realistic figure representation, while illustration, concept art, and figurative sculpture maintained strong anatomical foundations. The commercial art world—advertising, publishing, film—needed artists who could draw convincing human figures, ensuring continued demand for anatomical training.

Contemporary Anatomical Practice (1950-Present)

The past 75 years brought revolutionary changes: digital technology transformed both medical visualization and artistic practice, yet traditional anatomical illustration proved remarkably resilient. Contemporary anatomical practice spans traditional hand-drawn illustration, digital painting, 3D modeling, and interactive visualization—all coexisting and serving different needs.

Frank Netter and 20th Century Medical Illustration

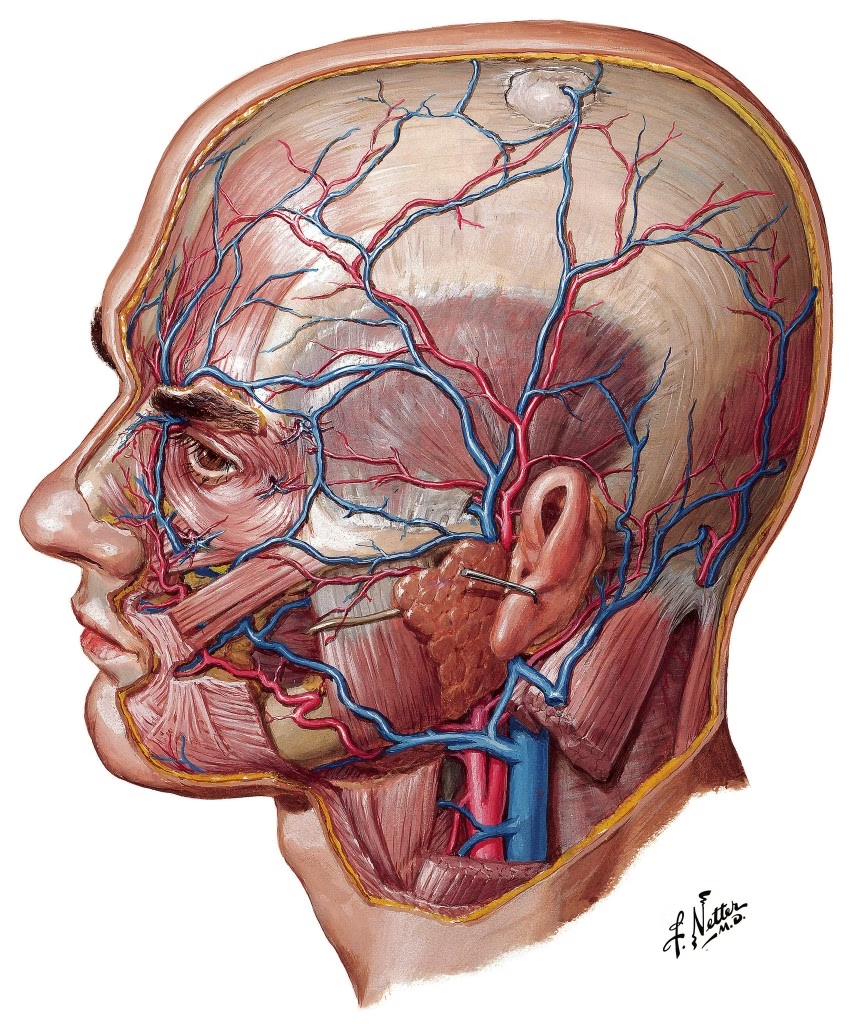

Frank H. Netter, MD (1906-1991) became the 20th century’s most influential medical illustrator, and his work remains the primary visual reference for medical students today.

Netter trained as a physician but supported himself through medical school by creating medical illustrations. After graduation, his illustration practice grew more successful than his medical practice. He eventually gave up seeing patients to focus entirely on medical illustration, though his medical training remained foundational to his work.

What distinguished Netter’s approach?

He thought like a physician while drawing like an artist. He understood not just what structures looked like but how they functioned, what clinical significance they had, what students and physicians needed to understand. This shaped his illustrative choices—what to emphasize, what viewpoint to show, how much detail to include.

His style was painterly and realistic but selectively so. Netter worked primarily in gouache (opaque watercolor), creating images with subtle color and texture that felt lifelike without being photographic. He could make anatomy beautiful while remaining accurate, encouraging students to engage with images rather than just reference them mechanically.

He emphasized spatial relationships and clinical relevance. Netter’s illustrations showed not just isolated structures but how they related to surrounding anatomy—essential for surgery and clinical procedures where you need to navigate from visible landmarks to deeper structures.

Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, first published as a complete collection in 1989, compiled decades of his work into a single comprehensive reference. It remains the best-selling anatomy atlas worldwide, used by medical students globally. Netter died in 1991, but his atlas continues in updated editions, with new illustrations by other artists working in his style.

The enduring success of Netter’s hand-painted illustrations in an era of CT scans, MRI, and 3D modeling demonstrates that traditional anatomical illustration continues to serve needs that technology hasn’t displaced.

Digital Revolution in Medical Visualization

Beginning in the 1970s and accelerating through the following decades, computer technology transformed medical imaging and visualization.

CT (computed tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) let physicians see inside living patients non-invasively. These weren’t static anatomical references but dynamic diagnostic tools showing individual patient anatomy in unprecedented detail.

3D reconstruction software could take CT or MRI scan data and build three-dimensional models of patient anatomy. Surgeons could plan complex procedures using patient-specific 3D models, rotating them, cutting virtual cross-sections, measuring distances and angles.

The Visible Human Project (1994) created complete 3D datasets of human anatomy. The National Library of Medicine obtained cadavers of a male and female donor, froze them, and took CT, MRI, and photographic cross-section images at tiny intervals through the entire body. The resulting datasets let software reconstruct any view of human anatomy.

Medical animation created visualizations impossible with static illustration—blood flowing through vessels, heart valves opening and closing, surgical procedures shown step-by-step from inside the body. These animations serve both education and patient communication.

Interactive anatomy software lets students explore anatomy on computers or tablets, clicking to identify structures, removing layers to reveal deeper anatomy, testing themselves with quizzes. The interactivity offers advantages over books: you can choose your own learning path, get immediate feedback, view the same anatomy from unlimited angles.

Yet despite these powerful technologies, traditional anatomical illustration persists in medical education. Why?

Clarity: A skilled illustrator can create images clearer than the visual noise of real tissue. Photographs and scans show everything; illustrations show what matters.

Idealization: Student anatomy needs to learn general human anatomy, not one individual’s variations. Illustrations can show composite, idealized anatomy.

Pedagogy: Illustrations can be designed specifically for teaching, with progressive complexity, strategic simplification, and emphasis on learning objectives. Technology shows reality; illustration explains concepts.

Accessibility: A textbook requires no technology, software, or connectivity. Illustrations work anywhere, anytime.

The contemporary reality is pluralistic: medical students use Netter’s atlas alongside 3D anatomy software, study cadavers and view CT scans, learn from both traditional illustrations and interactive digital resources. Each modality offers distinct advantages.

Contemporary Anatomical Artists

While medical illustration evolved digitally, fine art saw a neo-classical revival of interest in anatomical drawing.

Artists like Robert Liberace combine classical anatomical drawing skills with contemporary subject matter and aesthetics. Liberace teaches anatomical drawing workshops emphasizing direct observation, cast drawing, and écorché study—essentially the 18th-century French Academy curriculum updated for contemporary practice.

The American Society of Classical Realism and similar organizations promote figurative art based on thorough anatomical knowledge. These aren’t mere nostalgic returns to old methods but thoughtful engagements with anatomical tradition applied to contemporary artistic concerns.

Social media, particularly Instagram, created communities of artists sharing anatomical studies. Hashtags like #anatomyart, #figuredrawing, and #anatomystudy connect thousands of artists worldwide studying anatomy together, sharing drawings, critiquing each other’s work, and discussing techniques. This democratized access to anatomical community previously limited to formal art school attendance.

Contemporary anatomical artists work across media: traditional drawing and painting, digital art, sculpture, even tattooing (anatomical designs are popular tattoo subjects). The anatomical tradition proves adaptable to new contexts and audiences.

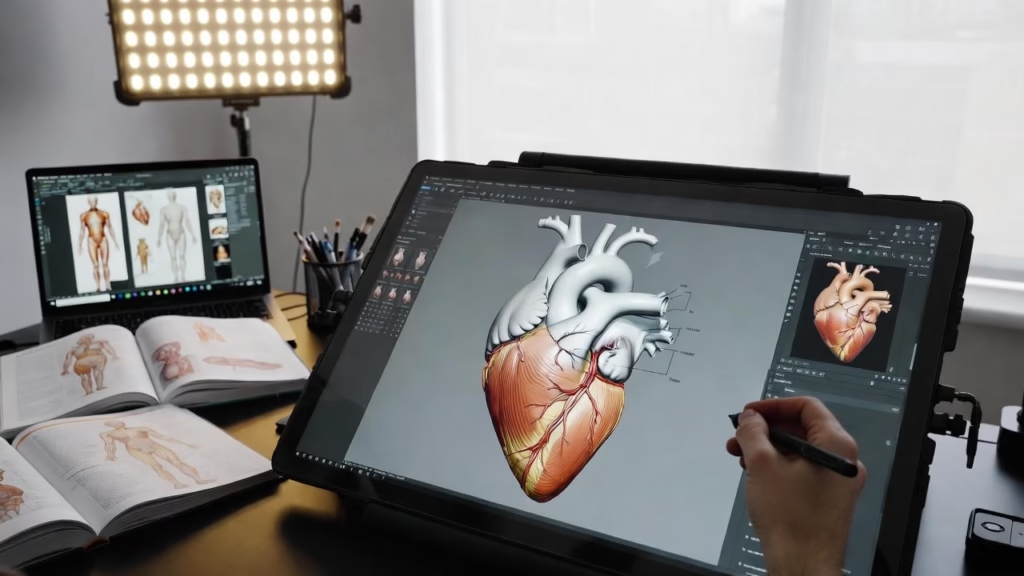

Digital Tools for Artists

Digital technology also transformed artistic anatomical study.

Drawing tablets (Wacom, iPad Pro, etc.) let artists create digital anatomical drawings with natural brush-like control. Software like Procreate, Photoshop, and Clip Studio Paint provides tools specifically useful for anatomical study—layers for separating muscle groups, ability to draw semi-transparent overlays showing deep structures, easy color coding.

3D reference software gives artists virtual anatomical models to study. Programs like Daz Studio offer poseable 3D figures. ZBrush lets digital sculptors study anatomy in three dimensions. These tools provide on-demand anatomical reference at any angle, in any lighting.

Online anatomy courses from Proko, New Masters Academy, and others make high-quality anatomical instruction available globally. Video demonstrations show drawing techniques. Interactive elements let students test their knowledge. Discussion forums connect students with instructors and peers.

360-degree anatomy viewers provide photographic reference of actual specimens or écorché sculptures from every angle. Artists can study how muscle forms change with viewpoint, how bones create surface landmarks, how anatomical structures appear in different positions.

These digital tools don’t replace traditional anatomical study—most contemporary anatomy courses still emphasize drawing from life and studying actual anatomy—but they supplement and enhance it. An artist might attend a figure drawing session with live model, then use 3D software to study specific anatomical questions that arose, then draw from écorché photos to understand the underlying muscular structure, then return to the live model with deeper understanding.

Medical Illustration as Modern Profession

Contemporary medical illustration requires both artistic skill and advanced education. Most medical illustrators hold master’s degrees from specialized programs like those at Johns Hopkins University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, or the University of Toronto.

The curriculum combines art (drawing, painting, digital illustration, 3D modeling, animation), science (anatomy, physiology, pathology, surgical procedures), and professional skills (client communication, project management, understanding medical context).

The Association of Medical Illustrators and Board of Certification of Medical Illustrators provide professional organization and certification, ensuring standards and advancing the field.

Career paths are diverse:

- Textbook and journal illustration: Traditional role creating images for medical publications

- Patient education: Developing materials explaining conditions and procedures to non-medical audiences

- Legal illustration: Creating exhibits for medical malpractice and personal injury cases

- Surgical illustration: Documenting procedures and creating surgical guides

- Veterinary illustration: Applying anatomical skills to animal anatomy

- 3D modeling and animation: Creating digital anatomical content for education and research

- Prosthetics and medical device development: Working with engineers to design and document medical devices

Despite predictions that photography and then digital imaging would eliminate the need for medical illustrators, the profession remains vital. The reason is simple: anatomical information needs to be communicated clearly, not just captured accurately, and that communication requires both artistic skill and deep anatomical understanding.

Techniques and Materials Through History

Understanding how anatomical drawings were physically created—the tools, materials, and practical challenges—helps us appreciate both the artistry and the difficulty of historical anatomical illustration.

Drawing Media Across Eras

Medieval-Renaissance (400-1600):

The earliest anatomical drawings used whatever writing materials were available. Medieval manuscripts used pen and ink on parchment (prepared animal skin). The ink was typically iron gall ink (made from oak galls, iron salts, and gum arabic), which dried brownish-black and was reasonably permanent.

Leonardo da Vinci preferred silverpoint—a silver wire drawn across paper specially prepared with a gritty ground (bone dust or powdered shells mixed with glue). Silverpoint created extremely fine lines, ideal for detailed work, but was unforgiving—you couldn’t erase marks, only build darker areas by adding more lines. The marks initially appeared gray but oxidized over time to warm brownish tones.

Red chalk (sanguine) and black chalk (pierre noire) became popular in the 1500s. These natural chalks allowed broader strokes than pen or silverpoint, useful for developing form and volume. Leonardo and other Renaissance artists used red chalk for anatomical studies, particularly for muscle and flesh tones. Black chalk worked well for structural elements.

Pen and ink remained standard for finished anatomical drawings. Artists would sketch in chalk or silverpoint, then create finished drawings in ink, using fine quills (from goose or swan feathers) or metal pens with carefully controlled nibs.

Baroque-Enlightenment (1600-1800):

Graphite pencil became available in the late 1500s but wasn’t widely used until the 1600s. Graphite offered advantages over chalk—cleaner, more controllable, erasable—though early graphite “pencils” were actually graphite chunks held in a holder, not the wood-encased form we know today.

Wash techniques combined pen and ink drawings with diluted ink or watercolor washes to add tone and volume. The illustrator would draw outlines and key details in pen, then build volume with graduated washes, creating three-dimensional effects.

Colored chalks (trois crayons technique) used red, black, and white chalk together. On toned paper (gray or tan), the artist would establish structure with black chalk, add flesh tones with red, and highlight with white. This created richly tonal anatomical studies.

For printed anatomical illustrations, the artist would draw on paper, then the drawing would be transferred to woodblocks (in the 1500s) or metal plates (in the 1600s-1700s) by specialized engravers. The original drawing and the final printed image were different objects, created by different people.

19th-20th Century (1800-2000):

Lithographic crayon allowed artists to draw directly on lithographic stones, creating prints without an intermediate engraving step. This directness preserved the artist’s original marks more faithfully.

Photography began serving as reference aid in the mid-1800s. Anatomists could photograph specimens, then illustrators would work from photographs (plus actual specimens when available), using photographic accuracy while applying illustrative clarity.

Colored pencil and gouache (opaque watercolor) became standard for finished anatomical illustrations in the 20th century. Frank Netter worked primarily in gouache, creating painterly illustrations with subtle color and sophisticated lighting.

Contemporary (2000-present):

Digital drawing tablets now allow artists to create anatomical illustrations entirely digitally. Programs like Photoshop, Procreate, and Clip Studio Paint provide brushes mimicking traditional media—pencil, pen, watercolor, oil paint—while adding digital advantages like layers, undo, easy color adjustment.

Many contemporary medical illustrators work in hybrid workflows: sketching traditionally, scanning sketches, completing illustrations digitally. Others work entirely digitally from start to finish. Still others create traditional artwork which is then scanned for publication.

Key Drawing Techniques

Cross-hatching involves creating parallel lines, then crossing them with lines at different angles, building up darkness and volume through line density. Leonardo perfected extremely fine cross-hatching, with lines less than a millimeter apart, creating subtle gradations that showed three-dimensional form.

The technique requires both technical control (keeping lines consistent and evenly spaced) and understanding of form (knowing where to build darkness, where to leave light, how line direction can suggest surface contours).

Stippling uses dots rather than lines to build tone. Denser dot placement creates darkness; sparse dots create light. Stippling can achieve very subtle gradations but is time-consuming, so it’s typically used for small areas requiring delicate rendering.

Wash and line combines crisp pen outlines with tonal washes. The pen establishes structure and edges; the wash builds volume and distinguishes planes. This technique dominated anatomical illustration in the 1700s-1800s, as it reproduced well in copper engraving.

Écorché technique refers not to a drawing method but to a systematic approach: progressively removing layers to reveal deeper structures. An écorché drawing might show multiple stages—skin, superficial muscles, deep muscles, bones—either as separate drawings or as a single drawing with portions at different stages of dissection.

Comparative views show the same structure from multiple angles—front, back, side, three-quarter views. This helps viewers construct a three-dimensional understanding from two-dimensional images.

Exploded view separates structures spatially, showing how they relate while making each individually visible. A hand might be shown with bones slightly separated from tendons, which are separated from muscles, all maintaining relative positions but pulled apart enough to see each clearly.

Color coding assigns specific colors to different systems: arteries red, veins blue, nerves yellow, lymphatics green. This convention, established in the 1700s, continues today because it immediately communicates structural identity.

Preservation and Dissection Challenges

Historical anatomists faced severe practical constraints that shaped what anatomical drawings could be created.

Without refrigeration, cadavers decomposed rapidly. In winter, a body might be usable for four days; in summer, less than 24 hours. This meant anatomists had to work fast and couldn’t always complete detailed studies of a single specimen.

The solution was to work systematically across multiple dissections. An anatomist might study the abdominal organs in one cadaver, the thorax in another, the head in a third. Finished anatomical drawings were often composites, synthesizing observations from multiple specimens.

Odor and health risks were significant. Decomposition produces terrible smells and potentially dangerous pathogens. Historical anatomists worked in poorly ventilated spaces (anatomical theaters had windows, but winter dissections were done with windows closed). Many anatomists developed health problems from repeated exposure to decomposing tissue.

Early preservation attempts had limited success. Injecting arteries with colored wax or tallow could maintain vascular structure temporarily. Salt, alcohol, and other preservatives slowed but didn’t stop decomposition. Dried preparations (skeletons, tendons) could be preserved indefinitely, but soft tissue couldn’t be maintained long.

Formaldehyde preservation, developed in the 1890s, finally provided effective long-term preservation. Specimens could be kept for months or years, allowing detailed, unhurried study. This single technological development transformed anatomical education and illustration.

Photography eventually provided a different solution: permanent records of anatomical preparations. A specimen could be photographed at its optimal state, then the photograph used as reference even after the specimen decomposed.

Collaborative Process: Artist and Anatomist

Most historical anatomical illustration involved collaboration between an anatomist (who performed dissection and understood the anatomy) and an artist (who created the drawings).

The anatomist would dissect and arrange the specimen for optimal viewing, identifying and explaining structures. The artist would observe, sketch, ask questions, and create the final illustrations. This division of labor was practical—few people had both deep anatomical knowledge and excellent artistic skill.

Communication challenges arose frequently. Anatomists used technical terminology; artists thought visually. An anatomist might say “show the insertion of the deltoid on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus,” which an artist needed to translate into visual decisions about viewpoint, lighting, how much of surrounding structures to show.

Artistic interpretation versus scientific accuracy created tension. Artists naturally wanted to create aesthetically pleasing images; anatomists wanted technically accurate documentation. The best anatomical illustrations balanced both—accurate enough for medical use, beautiful enough to engage viewers.

Famous partnerships produced landmark works:

- Vesalius + artists from Titian’s workshop (possibly Calcar) → De humani corporis fabrica

- Albinus + Jan Wandelaar → Tabulae sceleti et musculorum

- William Hunter + Jan van Rymsdyk → Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus

- Henry Gray + Henry Vandyke Carter → Gray’s Anatomy

Frank Netter was unique: he was both physician and artist, combining both roles in one person. This gave him advantages—he knew exactly what clinical perspectives mattered, what surgeons would encounter, what students needed to understand. His success partly validated the value of medical illustrators having substantial medical education, not just artistic skill.

Contemporary medical illustrators are more Netter-like: they receive significant scientific education alongside art training, enabling them to work more independently without constant anatomist supervision.

The Ethics of Historical Anatomical Study