When Janine lost her beloved daughter Shannan, she turned to a paintbrush for the first time in her life. Though she had never painted before, the canvas became a space where sorrow found color and silence found shape. What began as a personal journey through overwhelming grief grew into something larger—in 2024, Janine founded Healing Art Together, Inc., a nonprofit on Long Island committed to supporting those facing illness, trauma, grief, and adversity through creative expression.

Janine’s story isn’t unique. Across the United States and around the world, millions are discovering what she learned in her darkest moments: that art can be medicine for the heart, mind, and soul. Behind individual stories like hers lies a phenomenon quietly transforming mental health care—the explosive growth of trauma-informed art therapy.

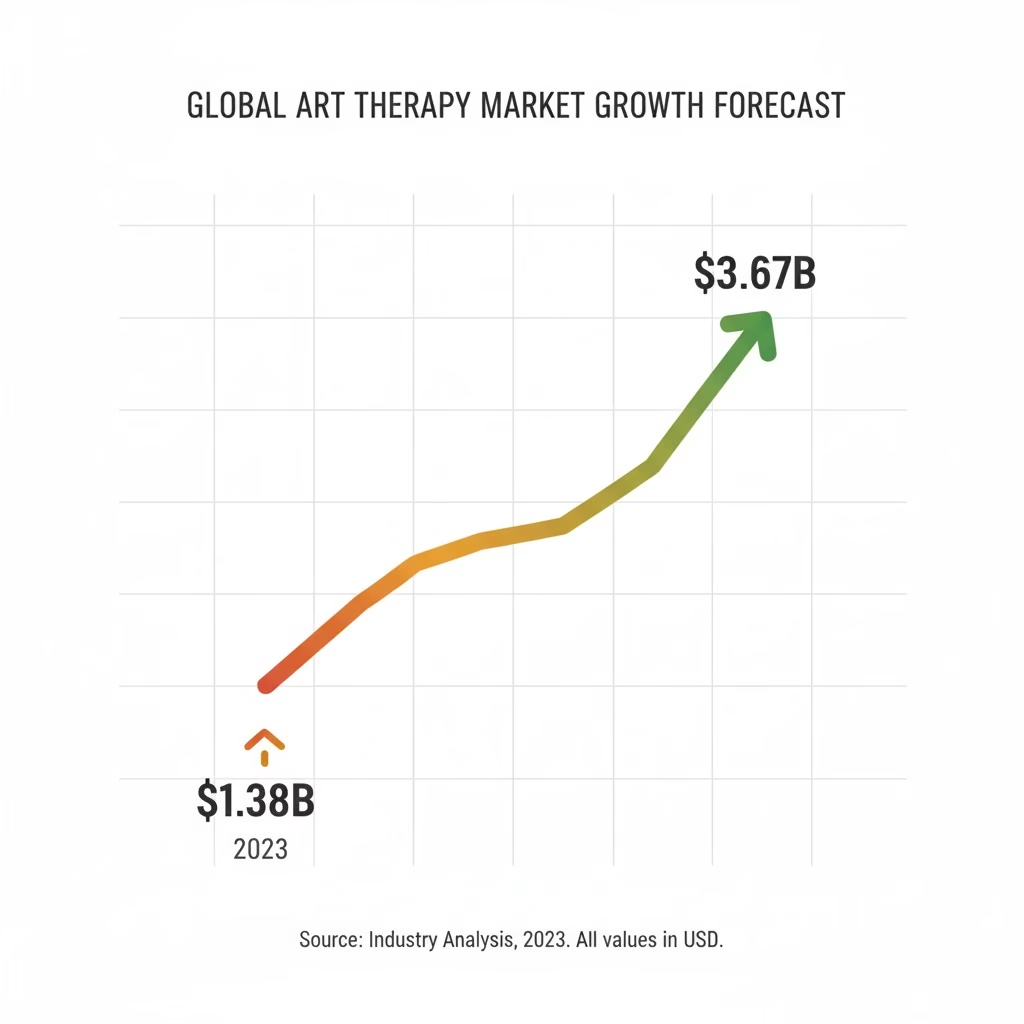

The numbers tell a striking story. The visual arts therapy market is projected to nearly triple from $1.38 billion in 2023 to $3.67 billion by 2030, representing annual growth of 15%. Art therapy services overall are expected to more than double from $2.5 billion to $5.8 billion by 2032. Job postings for art therapists are growing 22% faster than average occupations, with 26,660 new positions expected by 2029.

But these figures only hint at something deeper—a convergence of scientific validation, pandemic trauma, institutional acceptance, and cultural transformation that’s creating unprecedented demand for healing through creative expression. This isn’t just a market trend. It’s a fundamental shift in how we understand and treat trauma.

In this comprehensive analysis, we’ll explore the forces driving the trauma-informed art boom, examine the science validating these approaches, investigate who’s adopting them and why, and look ahead to what this movement means for the future of mental health care.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: Inside the Explosive Growth of Trauma-Informed Art

When market researchers project growth rates of 15% annually for any healthcare sector, it signals more than incremental change. The trauma-informed art therapy boom represents a seismic shift in treatment approaches, investment priorities, and consumer demand.

Table of Contents

Market Size & Staggering Growth Projections

The visual arts therapy market alone stood at $1.38 billion in 2023. By 2030, analysts project it will reach $3.67 billion—growth of 165% in just seven years. This 15% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) dramatically outpaces traditional pharmaceutical mental health treatments and reflects fundamental changes in how people seek healing.

Break down the numbers further, and the picture becomes even more compelling. Art therapy services broadly defined—including music therapy, dance/movement therapy, drama therapy, and other creative modalities—totaled $2.5 billion in 2023 and are projected to hit $5.8 billion by 2032, a 9.2% CAGR. Online art therapy platforms, virtually nonexistent a decade ago, grew from $2.86 billion in 2023 to a projected $8.72 billion by 2032, representing explosive 13.2% annual growth.

To put these figures in context, the overall psychotherapy market grows at roughly 5-6% annually. Trauma-informed art therapy’s growth rate is nearly triple that pace, suggesting a fundamental reordering of treatment preferences rather than simple market expansion.

What’s driving the dollars? Several converging factors: expanding insurance coverage, corporate wellness program adoption, school district implementation following pandemic trauma, and individual consumers increasingly willing to pay out-of-pocket for approaches that resonate with their values around holistic health.

The Practitioner Boom: Jobs Growing Faster Than Training Can Keep Up

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 22% job growth for art therapists between 2021 and 2031—more than three times the 7% average for all occupations. This translates to approximately 26,660 new positions by 2029, creating what industry insiders describe as a “perfect storm” of opportunity and challenge.

The challenge? Training programs can’t scale fast enough to meet demand. Art therapy requires a master’s degree, supervised clinical hours, and board certification—a multi-year pathway that creates an inevitable lag between job availability and qualified practitioners entering the field.

Currently, only about 5,000 board-certified art therapists (ATR-BC) practice in the United States, serving a population of 330 million. Compare this to the roughly 200,000 licensed clinical social workers or 100,000 psychologists, and the supply-demand imbalance becomes clear.

Universities are responding. The University of Cincinnati, for example, has seen enrollment in its pre-art therapy program surge, with students combining fine arts majors and psychology minors to prepare for graduate training. Antioch University, Lesley University, and other institutions are expanding their art therapy graduate programs, but building new faculty, clinical supervision capacity, and practicum sites takes time.

For those entering the field now, the prospects are exceptional. Entry-level art therapists earn $45,000-$55,000 annually, with experienced practitioners in hospital or private practice settings commanding $65,000-$85,000. In high-demand urban markets or specialized corporate wellness roles, salaries can exceed $100,000.

Geographic Hotspots: Where Trauma-Informed Art Is Thriving

North America dominates the global market, accounting for over 35% of revenue in 2025. This leadership stems from several factors: high mental health awareness, established healthcare infrastructure, favorable (though still incomplete) reimbursement policies, and cultural openness to alternative therapeutic approaches.

Within North America, specific regions show particularly strong growth. The Northeast corridor (Boston to Washington D.C.) hosts the highest concentration of practitioners and programs. California leads in corporate wellness adoption, with tech companies and entertainment industry organizations implementing creative therapy initiatives for employee mental health. Texas and Florida show rapid growth in school-based programs, responding to both pandemic impacts and natural disaster trauma.

Europe represents the second-largest market at roughly 25% of global revenue. The United Kingdom, Germany, and Nordic countries lead adoption, often integrating art therapy into national healthcare systems with government funding. The British Association of Art Therapists reports steady membership growth, and the NHS has expanded art therapy services particularly for healthcare worker burnout—a focus intensified by pandemic experiences.

But the real story is Asia Pacific, which shows the fastest regional growth at over 30% CAGR. China and India are recognizing therapeutic value in creative expression, with rising middle-class populations seeking alternatives to pharmaceutical-focused treatment. Cultural factors play a role here: many Asian traditions already incorporate creative practices for wellness, creating natural bridges to formalized art therapy approaches.

Japan has seen particular interest in art therapy for elderly populations facing dementia and social isolation. South Korea’s integration of art therapy into educational settings for student mental health represents another growth driver. The diverse cultural landscape means regional adaptations—traditional calligraphy in China, mandala creation in India—blend with evidence-based Western approaches to create culturally resonant hybrid models.

Latin America and the Middle East/Africa show more gradual but steady growth. Brazil and Mexico lead in Latin America, with art therapy increasingly incorporated into public health systems. In the Middle East, the UAE and progressive Gulf states are adopting creative therapies, while South Africa shows interest in community-based trauma healing programs addressing historical and ongoing violence.

Investment Follows Evidence: Major Funding Initiatives

When major foundations and government agencies invest millions in a field, it signals more than optimism—it demonstrates evidence-based confidence in measurable outcomes.

In January 2025, the Prebys Foundation launched a groundbreaking $5.2 million initiative called “Healing Through the Arts and Nature,” awarding grants to 59 nonprofits across San Diego County. These grants support programs serving youth, veterans, justice-impacted individuals, and historically underserved communities through activities ranging from playwriting and painting to farming and surfing—all designed to enhance well-being through creative engagement with arts and nature.

The initiative explicitly embraces “social prescription”—a concept gaining traction in healthcare where providers prescribe non-clinical services, including community arts activities, to prevent or treat health issues. This approach, common in the UK’s NHS, is now expanding in the United States as evidence mounts that arts engagement can be as impactful as medication for certain conditions.

The National Endowment for the Arts has expanded its arts-health funding portfolio significantly since 2020, supporting research, program development, and practitioner training. The January 2024 White House Summit on Arts and Culture—co-hosted with the NEA—marked the first-ever federal convening specifically addressing how arts contribute to health and well-being, signaling policy-level recognition of the field’s importance.

Corporate investment presents perhaps the most dramatic shift. Companies globally will spend over $60 billion on employee mental health and wellness programs by 2026, and art therapy is capturing a growing share. Organizations recognize that creative interventions address stress, boost innovation, improve team cohesion, and provide distinctive benefits that help attract and retain talent in competitive markets.

Insurance coverage expansion, while slower than advocates would like, continues incrementally. More Medicare Advantage plans now cover art therapy for specific conditions. Some state Medicaid programs have added coverage. Major private insurers are piloting reimbursement programs, particularly when art therapy is integrated with traditional psychotherapy for trauma treatment.

The investment landscape reflects a maturing field moving from alternative niche to evidence-based mainstream intervention.

The Trauma Pandemic: How COVID-19 Catalyzed the Healing Arts Movement

If a single inflection point explains why trauma-informed art is surging now rather than a decade ago, it’s the COVID-19 pandemic. While art therapy existed long before 2020, the pandemic created a perfect storm of mental health crisis, accessibility innovation, and collective trauma that permanently altered the field’s trajectory.

Mental Health in Freefall: The Crisis That Changed Everything

The pandemic’s mental health toll exceeded even pessimistic early predictions. By mid-2021, U.S. anxiety rates had tripled compared to 2019 levels. Depression rates quadrupled. Post-traumatic stress symptoms became common even among those who didn’t lose loved ones—the collective experience of sustained threat, disruption, and uncertainty created what mental health professionals termed a “trauma pandemic” layered over the biological one.

Children suffered particularly acute impacts. School closures lasted months or years depending on location, severing social connections during critical developmental windows. A 2022 study found that anxiety and depression measures among children showed significant increases, with inattention, hyperactivity, and behavioral problems spiking across samples.

For many children, schools had provided their only mental health support. When buildings closed, that safety net vanished. Parents struggled with suddenly becoming full-time caregivers, educators, and emotional supports while managing their own stress. The resulting family tension created a pressure cooker environment.

Healthcare workers faced what the American Art Therapy Association’s 2020 survey termed “an unfolding mental health crisis” among frontline professionals. Rates of moral distress, compassion fatigue, and burnout soared as medical staff confronted daily death tolls, impossible triage decisions, and fear of bringing infection home to families.

Domestic violence surged during lockdowns, with survivors and children trapped at home with abusers. Calls to crisis hotlines increased dramatically. Substance abuse rates climbed as people sought escape from unrelenting stress.

U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy identified loneliness as a particular pandemic legacy, warning that social isolation’s health impacts rival smoking or obesity. The Foundation for Art & Healing made addressing this “loneliness epidemic” central to its mission, launching initiatives specifically designed to foster connection through creative expression.

Into this crisis stepped art therapy—offering something talk therapy alone couldn’t always provide.

When Words Failed: Art as Pandemic Coping

Scroll through social media during 2020-2021 lockdowns and a pattern emerges: People shared sourdough loaves, home gardens, and artwork. These weren’t just boredom-driven hobbies—they were instinctive coping mechanisms.

Research supports what experience suggested. A 2024 study published in Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts found that individuals who gravitated toward artistic activities during COVID-19 reported significantly better mental health outcomes than those who didn’t engage creatively. Drawing, painting, music-making, and other creative acts correlated with reduced stress, better emotional regulation, and increased resilience.

Yale School of Medicine’s “Mindful: Mental Health Through Art” exhibit, launched in March 2024, showcased artwork created by medical students and professionals during the pandemic. One contributor wrote of her self-portrait created during peak COVID isolation: “Turning to the visual arts enabled me to better understand and support my mental health. This piece serves as a testament to the profound emotional benefits of creativity.”

The pandemic validated what art therapists had long known: creative expression accesses healing pathways beyond verbal processing. When people felt too overwhelmed for traditional talk therapy, when words couldn’t capture the surreal horror of daily life under pandemic conditions, when isolation made in-person therapy impossible—art provided an outlet.

Organizations responded rapidly. The Foundation for Art & Healing launched “Stuck at Home Together,” offering online creative expression opportunities. Universities developed quick-deploy online art therapy programs. Community organizations distributed art supply kits to families in quarantine.

The “Quarantine Family Toolkit” created by art therapist Kristin Ramsey, ATR-BC, LPC, provided parents with accessible activities to help children process COVID-related fears and disruption. It included art activity instructions, sample daily schedules for working/learning from home, and guidance on talking with children about the pandemic.

What might have remained niche offerings became mainstream necessities, introducing millions to trauma-informed creative practices for the first time.

Schools on the Frontlines: Trauma-Informed Arts Education Goes Mainstream

Before COVID, trauma-informed arts programming in schools existed primarily in communities recovering from acute disasters—wildfires, school shootings, hurricanes. The pandemic made every school a recovery site.

The Butte County Office of Education in Northern California pioneered a model that others would replicate nationwide. Following the catastrophic 2018 Camp Fire that killed 86 people and destroyed the town of Paradise, trauma-informed arts educators were deployed into schools to help students process fear, grief, and loss. Children used painting, music, drama, and movement to express emotions beyond their verbal capacity.

When COVID hit, Butte County’s existing infrastructure and expertise became invaluable. The program expanded and adapted for virtual delivery, and other districts took notice. What had been viewed as disaster-specific intervention became recognized as essential ongoing support.

Research validated the approach. A 2021 randomized controlled trial published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health studied online art therapy in elementary schools during COVID. Children who participated in emotion-based directed drawing and mandala creation showed measurable improvements in mental health markers compared to control groups.

Drumming circles emerged as particularly effective. Music therapist Naas, working with students in Butte County, explained: “Drumming is a powerful activity that creates community. What I notice about drumming with children is that students become excited, motivated, and fully engaged at the very start. They reach for the rhythms and begin exploring the drums right away.” The activity builds empathy through ensemble listening, self-expression balanced with taking turns, and physical release of emotional energy.

The Art of Education, a major professional development provider for art teachers, developed specific trauma-informed teaching resources. Their guidance emphasized that art rooms can be safe spaces for students to express themselves, particularly when that expression includes trauma responses. They stressed that while art teachers aren’t licensed therapists, creating art in classrooms allows students to explore and process feelings in supportive environments.

By 2024, trauma-informed arts education had moved from specialized intervention to standard practice in many districts. The shift reflects recognition that ongoing community stress—poverty, violence, family instability—creates chronic trauma requiring the same careful approaches developed for acute disaster response.

At a March 2024 summit organized by the White House Domestic Policy Council and National Endowment for the Arts, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said of music and arts: “I’ve prescribed a lot of medicines as a doctor over the years. There are few I’ve seen that have that kind of extraordinary, instantaneous effect.”

The Telehealth Revolution: Technology Removes Barriers

Perhaps the pandemic’s most enduring impact on art therapy is the permanent expansion of virtual delivery.

Before 2020, art therapy happened almost exclusively in person. Therapists and clients needed to share physical space, materials, and the artifacts created. The sensory experience—texture of clay, smell of paint, sound of tearing paper—seemed integral to the therapeutic process.

COVID forced rapid innovation. Art therapists transitioned to video platforms, adapted techniques for virtual delivery, and discovered something surprising: for many applications, virtual art therapy worked equally well.

Research bore this out. Studies comparing virtual to in-person art therapy for mood disorders, anxiety, and even some trauma applications found equivalent efficacy. The key was thoughtful adaptation—using materials clients could access at home, adjusting camera angles to share artwork, finding ways to maintain therapeutic relationship through screens.

Virtual delivery proved especially effective for individuals who’d previously faced access barriers. Rural residents who lived hours from the nearest certified art therapist could now access specialists anywhere in their state or country. People with mobility limitations found virtual sessions easier than traveling to clinics. Those with social anxiety or agoraphobia sometimes engaged more readily from the safety of home.

Online art therapy platforms proliferated. The market for these services grew 240% during the pandemic’s peak and has sustained much of that growth. Platforms now offer one-on-one sessions, group workshops, self-guided courses, and hybrid models combining synchronous therapist interaction with asynchronous creative assignments.

The technology expansion didn’t eliminate in-person practice—many therapists and clients still prefer face-to-face sessions, particularly for complex trauma or when building new therapeutic relationships. But hybrid models have become standard, with therapists offering both options and clients choosing based on preference and circumstances.

This democratization of access will likely prove the pandemic’s most lasting contribution to the field. Geographic and logistical barriers that once kept trauma-informed art therapy available only to privileged populations with time, mobility, and proximity to urban centers have substantially diminished.

The Science Behind the Surge: Why Trauma-Informed Art Works

Market growth and cultural acceptance mean little without scientific foundation. Fortunately for the field, neuroscience research over the past two decades has provided increasingly clear explanations for why art-based approaches prove particularly effective for trauma—answers that go far beyond the feel-good assumptions that long relegated creative therapies to “alternative” status.

Trauma Lives in the Body: The Neuroscience Basics

Understanding why art therapy works for trauma starts with understanding how trauma affects the brain and nervous system.

When someone experiences trauma—whether acute (a car accident, assault) or chronic (ongoing abuse, war exposure)—the experience doesn’t just create troubling memories. Trauma physically alters brain structure and function, particularly in three key regions.

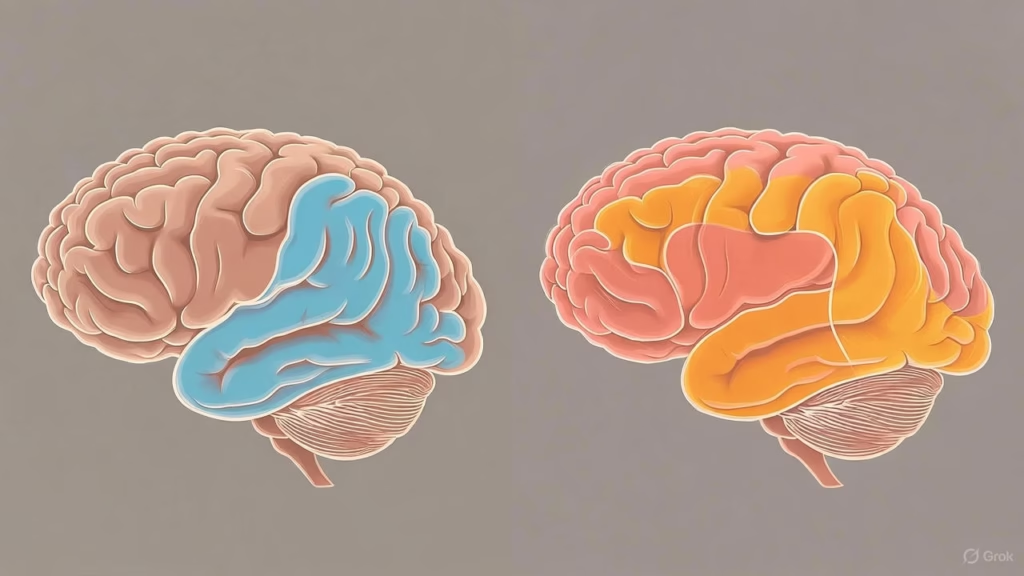

The amygdala, the brain’s threat-detection center, becomes hyperactive. It stays on high alert, triggering fight-flight-freeze responses to stimuli that merely resemble the original trauma. A combat veteran might dive for cover at a car backfire. A sexual assault survivor might freeze when someone unexpectedly touches their shoulder.

The hippocampus, responsible for contextualizing memories in time and space, often shows reduced volume in trauma survivors. This helps explain why traumatic memories feel timeless—happening in an eternal present rather than safely contained in the past. The person experiencing a flashback isn’t just remembering the event; their brain and body react as if it’s happening now.

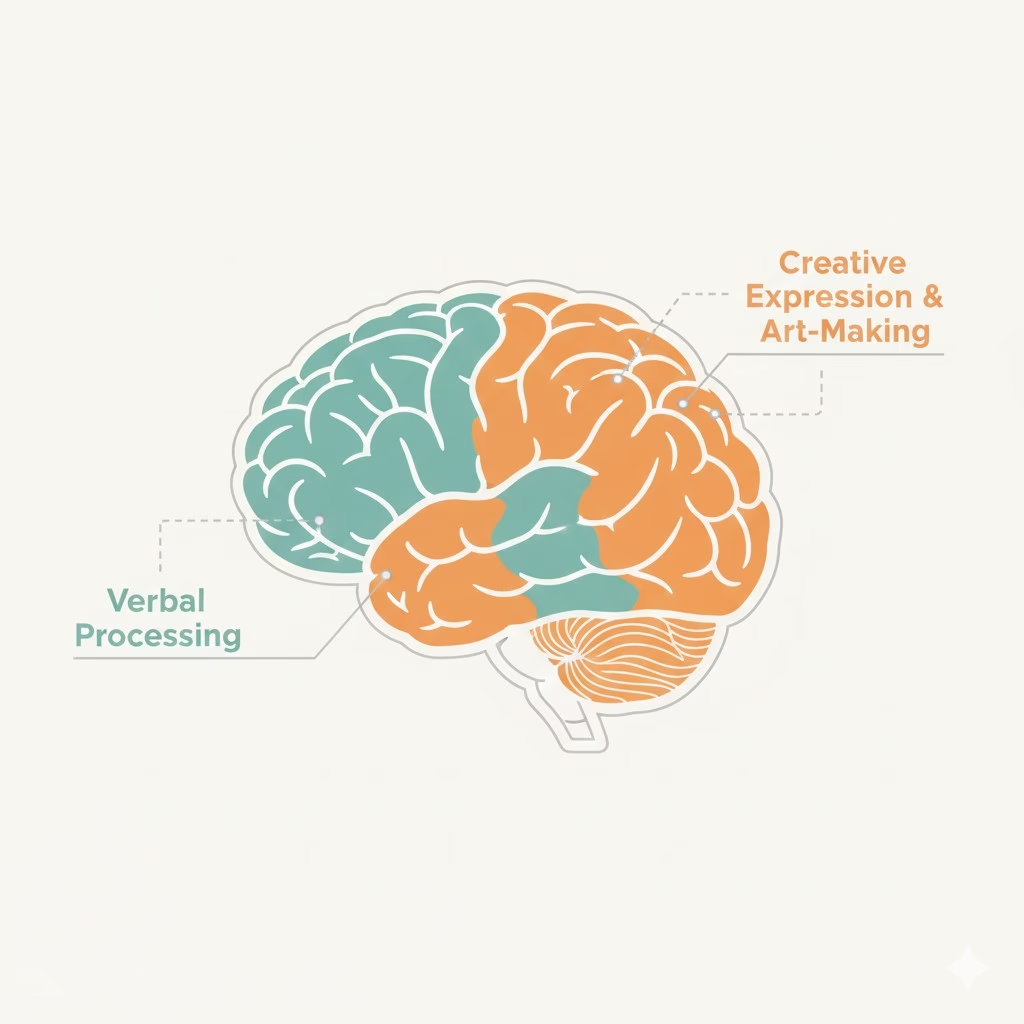

Perhaps most critically for understanding art therapy’s effectiveness, trauma affects the prefrontal cortex and particularly Broca’s area—brain regions associated with language production and verbal processing. Brain imaging studies show these areas literally “go offline” during trauma recall.

This neurological reality creates what trauma expert Dr. Bessel van der Kolk calls the “speechless terror” of trauma. Survivors often report that their traumatic experiences exist “beyond words”—not as a poetic metaphor but as literal neurological fact. The parts of the brain that translate experience into language don’t function normally when trauma is activated.

Traditional talk therapy—which relies entirely on verbal processing—thus faces an inherent limitation. It’s not that talk therapy doesn’t work for trauma (it often does, particularly cognitive-behavioral approaches), but it requires engaging brain systems that trauma has compromised.

Trauma also “lives in the body” through the nervous system. The polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, explains how trauma creates chronic dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system—the system governing automatic functions like heart rate, breathing, and digestion. Trauma survivors often exist in persistent states of hyperarousal (anxiety, panic, hypervigilance) or hypoarousal (shutdown, dissociation, numbing).

Body-based or “somatic” understanding of trauma recognizes that healing must address these physiological patterns, not just cognitive beliefs or verbal narratives.

Art Bypasses the Blockage: Alternative Neural Pathways

Art-making engages brain networks differently than language-based processing. This isn’t speculation—functional MRI (fMRI) studies clearly show distinct activation patterns when people create art versus when they talk or write about experiences.

Visual art creation activates the visual cortex, motor cortex (physical movements of drawing, painting, sculpting), and reward centers (pleasure from creative flow). Music engages auditory processing, motor coordination (playing instruments), and emotional processing centers. Dance and movement activate proprioceptive awareness (sense of body in space), motor planning, and emotional expression systems.

Critically, these pathways remain accessible even when language centers shut down during trauma activation. A person frozen in speechless terror can still paint. Someone whose verbal narrative feels inadequate can express through movement what words cannot capture.

This neurological reality explains observations art therapists have made for decades: clients often create artwork depicting trauma before they can verbalize what happened. Children especially—whose language development may not yet support complex emotional expression—can show through drawings what they cannot say.

But art therapy isn’t simply an end-run around blocked language centers. Research by Dr. Cathy Malchiodi and others shows that art-making supports neural coherence and self-integration—helping different brain regions communicate more effectively. Creating visual representations of trauma can help the hippocampus properly contextualize frightening memories in past rather than present tense. The sense of control and agency in the creative process can help regulate the overactive amygdala.

A 2024 meta-analysis published in Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy reviewed multiple studies on visual arts therapy for traumatic experiences. The researchers found significant positive effects across measures of PTSD symptoms, anxiety, depression, and general psychological well-being. Effect sizes suggested that art therapy approaches were comparable to or exceeded other trauma interventions for certain populations and trauma types.

The research particularly highlighted art therapy’s effectiveness for dissociation—a common trauma response where people feel disconnected from their bodies, emotions, or sense of identity. Because art-making is fundamentally embodied (physical movement creates visible artifact), it helps ground dissociative individuals back into their bodies and present moment awareness.

Measurable Outcomes: What the Research Shows

Beyond understanding mechanisms, practical outcomes matter. Does trauma-informed art therapy actually produce measurable improvements in symptoms and functioning?

The evidence increasingly says yes, though with important nuances about what works for whom.

A comprehensive review published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health examined art therapy’s effectiveness for children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis found consistent improvements across multiple measures: reduced anxiety, improved sleep quality, decreased depression scores, better emotional regulation, and enhanced psychological well-being.

One study within that review couldn’t identify post-intervention differences in anxiety, depression, or mindfulness between treatment and control groups, but found significant reduction in hyperactivity scores across the full sample—suggesting drawing-based interventions provided meaningful mental health improvement even when all measures didn’t reach statistical significance.

Research on art therapy for healthcare worker burnout showed particularly strong outcomes. A 2025 randomized controlled trial published in BMJ Public Health studied art therapy groups for National Health Service workers across four London hospitals. Healthcare professionals who participated in six weekly 90-minute sessions showed significant reductions in burnout scores and mental distress compared to waitlist controls. The intervention, adapted from programs designed for oncology and palliative care doctors, incorporated trauma-informed methods developed specifically for pandemic staff support.

For cancer patients, multiple studies demonstrate that art therapy reduces emotional distress, decreases need for pain medication, and can contribute to shorter hospital stays when integrated into comprehensive care. The psychological benefits—reduced anxiety about treatment, improved ability to express fears and hopes, sense of control through creative choice—translate into measurable physiological impacts.

Research on cortisol levels provides direct evidence of art therapy’s stress-reduction effects. Studies measuring stress hormone levels before and after art-making sessions consistently find significant decreases. This biological marker confirms what participants report subjectively: the creative process genuinely reduces physiological stress, not just psychological perception of stress.

For older adults with dementia, art therapy shows remarkable benefits. Programs in memory care facilities report 40% reductions in behavioral incidents—agitation, aggression, wandering—among residents who participate regularly in structured art activities. Cognitive stimulation, emotional expression, and social connection all contribute to these improvements.

A 2020 pilot study on trauma-informed art therapy for mothers and children in domestic violence shelters (conducted across sites in the United States and South Africa) found improvements in both maternal mental health and child behavioral outcomes. The program specifically addressed mother-child relationships damaged by exposure to intimate partner violence, using collaborative art-making to rebuild attachment bonds.

Veterans programs show particular promise. The Department of Veterans Affairs has expanded art therapy offerings substantially, with research documenting reduced PTSD symptoms, improved emotional regulation, and better social reintegration outcomes. The nonverbal nature of creative expression proves especially valuable for combat trauma that survivors describe as “unspeakable.”

Meta-analyses provide the strongest evidence by combining results across multiple studies. A 2018 review in Frontiers in Psychology found significant positive effects of art therapy on mental health across diverse populations and settings. Effect sizes were particularly robust for anxiety reduction and emotional expression.

Important caveats exist. Research quality varies—some studies use small samples or lack rigorous controls. Long-term outcomes need more investigation; most studies measure immediate or short-term (3-6 month) effects. Comparative effectiveness research (art therapy versus other trauma treatments) remains limited, making it difficult to say definitively when art-based approaches should be first-line treatment versus complementary intervention.

But the trajectory is clear: evidence supporting trauma-informed art therapy is growing in volume, rigor, and consistency. The field has moved well beyond anecdotal success stories to documented, measurable outcomes that meet standards for evidence-based practice.

Beyond PTSD: Trauma-Informed for Complex, Developmental, and Intergenerational Trauma

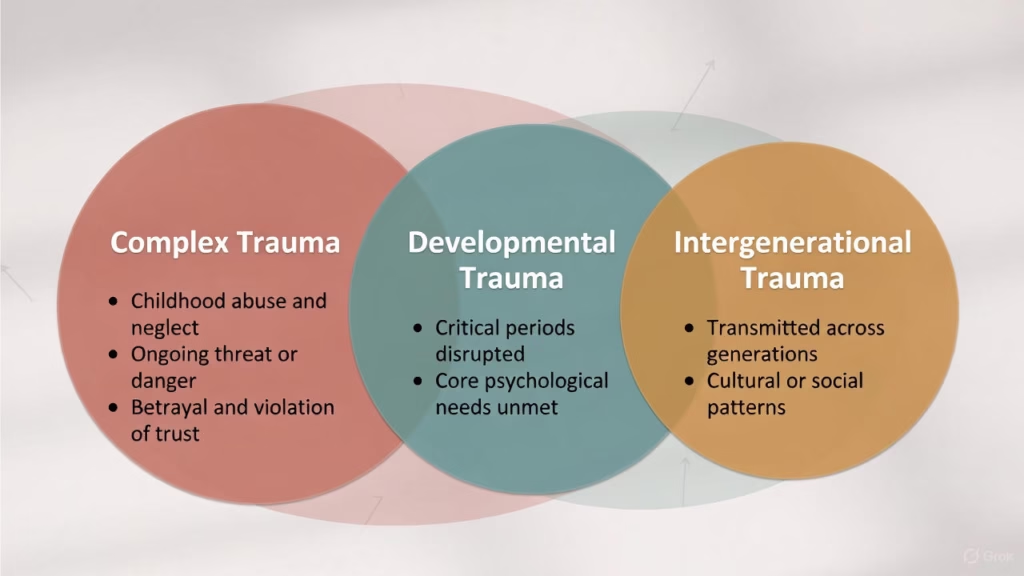

While much trauma research focuses on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—the diagnostic category following discrete traumatic events—trauma-informed approaches address a broader spectrum of traumatic stress.

Complex trauma refers to exposure to multiple or prolonged traumatic events, often interpersonal and beginning in childhood. This includes ongoing physical or sexual abuse, chronic neglect, domestic violence exposure, and community violence. Complex trauma affects personality development, emotional regulation, relationship patterns, and sense of self in ways that single-incident PTSD often doesn’t.

Developmental trauma occurs when children experience chronic threat or disruption during critical developmental periods. The trauma doesn’t just create frightening memories—it interferes with normal development of emotional regulation, attachment security, and neurological integration. Adults who experienced developmental trauma often struggle with shame, self-loathing, difficulty trusting others, and emotional dysregulation that seems disproportionate to current circumstances.

Intergenerational or historical trauma describes trauma effects transmitted across generations. Holocaust survivors’ descendants, for example, show higher rates of anxiety and stress-response dysregulation even without direct trauma exposure. Indigenous communities deal with historical trauma from genocide, forced assimilation, and ongoing oppression—trauma that affects community members generations removed from original events.

For these complex trauma presentations, trauma-informed art therapy offers particular advantages.

The emphasis on safety—creating environments where clients feel in control, respected, and not pressured—addresses the trust violations central to interpersonal trauma. The pacing flexibility allows work at speeds appropriate for each individual rather than protocol-driven timelines that may feel retraumatizing.

The nonverbal nature proves crucial for developmental trauma survivors who may have experienced trauma before acquiring language, making verbal processing literally impossible for those experiences. Art provides a medium to access and express preverbal trauma that talk therapy alone cannot reach.

For intergenerational trauma, creative expression offers ways to connect with cultural traditions (traditional art forms, music, storytelling) while processing historical pain. Art therapists working with Indigenous populations, for example, often integrate culturally specific creative practices that honor heritage while supporting healing.

A trauma-informed framework also emphasizes empowerment and collaboration—countering the powerlessness central to many trauma experiences. In sessions, clients choose materials, direct the creative process, and control what they share. This sense of agency becomes itself therapeutic, building capacities for self-determination that trauma undermined.

Dr. Cathy Malchiodi’s “Circle of Capacity” framework exemplifies this approach. Rather than focusing on trauma symptoms and deficits, it emphasizes expanding regulation and recuperative experiences through creative engagement. The framework reframes trauma recovery as a process of building capacity—for emotional regulation, social connection, meaning-making, and joy—rather than simply symptom reduction.

This broader, more nuanced understanding of trauma positions art therapy not just as alternative treatment for diagnosed PTSD, but as comprehensive approach for the many varieties of traumatic stress that affect human wellbeing.

What “Trauma-Informed” Actually Means: More Than Just Making Art

The term “trauma-informed” has become ubiquitous across healthcare, education, and social services—sometimes diluted into meaninglessness. In the context of art therapy, it has specific, substantive meaning that distinguishes therapeutic practice from recreational art-making or general art education.

The Core Principles: Safety, Trust, and Empowerment

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) established six core principles for trauma-informed approaches that have become foundational across the field:

Safety means creating physical and emotional environments where clients feel protected from re-traumatization. In art therapy, this includes careful attention to materials (some clients find sharp tools triggering), seating arrangements (trauma survivors often need ability to see exits and control who sits near them), and pacing (never pushing clients to address traumatic content before they’re ready).

Trustworthiness and Transparency involves clear communication about what will happen in sessions, consistent boundaries, and therapist reliability. Art therapists practicing trauma-informed approaches explain processes, honor stated boundaries, and avoid surprises that might activate trauma responses.

Peer Support recognizes that connection with others who’ve experienced similar struggles can be profoundly healing. Group art therapy capitalizes on this, creating communities of mutual support through shared creative expression.

Collaboration and Mutuality emphasizes that therapist and client work as partners rather than expert/patient hierarchy. In practice, this means clients have genuine choice about materials, topics, and pace. The therapist facilitates rather than directs.

Empowerment, Voice, and Choice counters the powerlessness central to trauma experiences. Trauma-informed art therapy offers clients control over their creative process as a way of rebuilding sense of agency in their lives.

Cultural, Historical, and Gender Considerations means recognizing how identity shapes trauma experiences and healing processes. This includes understanding historical trauma in marginalized communities, gender-based violence patterns, and cultural differences in emotional expression and help-seeking.

These aren’t abstract principles—they translate into concrete practices that differentiate trauma-informed art therapy from general therapeutic work or art education.

Neurosequential Approach: Stabilize, Process, Integrate

Trauma-informed art therapy typically follows a phased approach aligned with neuroscience understanding of how trauma healing occurs.

Phase 1: Stabilization focuses on establishing safety, building emotional regulation capacities, and developing resources before addressing traumatic content directly. Art activities in this phase emphasize grounding (connecting to present moment through sensory engagement with materials), containment (creating boundaries and sense of control), and positive experiences (accessing joy, playfulness, beauty).

Therapists might use structured activities like mandala coloring, which research shows reduces anxiety through rhythmic, predictable motor movements and contained creative space. Clay work provides powerful grounding through its tactile, heavy, earthiness. Creating “safe place” imagery helps establish internal resources clients can access when distressed.

This phase respects what neuroscience teaches about trauma recovery: the nervous system must stabilize before cognitive processing can occur. Pushing trauma survivors to “talk about it” before their systems can tolerate such activation often backfires, increasing symptoms.

Phase 2: Trauma Exploration involves safely processing traumatic memories and experiences—but with crucial caveats. Trauma-informed approaches use principles of pendulation (moving between distress and safety) and titration (working with trauma material in small, manageable doses).

Art provides a unique tool for creating psychological distance from overwhelming content. A client can depict traumatic experiences in the third person (“the scared child” rather than “I was scared”), use metaphor (storm imagery for emotional chaos), or work abstractly (colors and shapes representing feelings without narrative).

This distance allows engagement with traumatic material without full re-experiencing—accessing the content enough to process it, but with enough buffer to prevent re-traumatization. The art object itself becomes a container holding difficult experiences at safe remove.

Phase 3: Integration focuses on making meaning of experiences, integrating traumatic memories into coherent life narrative, and building future orientation. Art in this phase might include timelines showing past-present-future, collages representing identity that includes but isn’t defined by trauma, or creative expressions of hopes and dreams.

The goal is helping traumatic experiences become memories—events that happened in the past rather than perpetually recurring present-tense attacks.

This phased approach isn’t rigidly linear. Clients may cycle back to stabilization during particularly difficult periods, then return to processing work when ready. The sequence provides framework, not prescription.

Modalities Beyond Canvas: Music, Movement, Drama, and More

While “art therapy” often conjures images of painting and drawing, trauma-informed creative approaches encompass diverse modalities, each offering unique therapeutic properties.

Visual arts (painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, collage) remain most common. They provide tangible artifacts clients can keep, revisit, or destroy as part of processing. The variety of media—from gentle watercolors to aggressive charcoal marks to three-dimensional clay—allows matching materials to therapeutic needs and client preferences.

Music therapy uses listening, playing instruments, songwriting, and sometimes singing to access emotional processing, regulate nervous system arousal, and build social connection through ensemble playing. Music’s capacity to shift emotional states rapidly—what Surgeon General Murthy described as having “extraordinary, instantaneous effect”—makes it particularly valuable for regulation work.

Rhythm-based interventions like drumming have specific trauma applications. The predictable, repetitive nature helps regulate dysregulated nervous systems. The physical release through hitting drums provides outlet for energy mobilized by fight-flight responses. Group drumming creates sense of safety through synchronized experience.

Dance/movement therapy directly addresses trauma’s embodiment. Since trauma often leaves people feeling disconnected from their bodies or trapped in frozen defensive responses, mindful movement can help restore body awareness, release held tension, and reclaim physical agency.

Approaches range from gentle stretching and breathing exercises to expressive dance to formal movement sequences. The focus isn’t aesthetic performance but authentic embodied expression.

Drama therapy uses role-play, improvisation, storytelling, and enactment to explore experiences from different perspectives. Taking on roles allows experimentation with different responses to situations, practicing boundaries, and finding voice.

For trauma survivors whose sense of self fragmented through overwhelming experiences, drama therapy’s emphasis on trying on different identities can support reintegration. Narrative approaches help construct coherent stories from fragmented traumatic memories.

Expressive writing combines verbal processing with creative expression through poetry, journaling, story-writing, or letter composition (often letters never sent to people who caused harm). Writing provides structure that pure verbal processing may lack while allowing depth that visual arts sometimes can’t capture.

Integrated expressive arts combines modalities—perhaps starting with movement, creating visual art from what emerged, then writing about the artwork. This multi-modal approach mirrors the multi-sensory nature of traumatic experiences and healing.

Choosing modalities depends on client preferences, cultural background, trauma type, and therapeutic goals. Some survivors find visual arts too exposing, preferring music’s abstraction. Others find movement essential to releasing trauma held in bodies. Skilled trauma-informed therapists adapt to client needs rather than imposing favored modalities.

A Session Walkthrough: What Actually Happens

Understanding trauma-informed art therapy abstractly differs from knowing what actually occurs in sessions. While approaches vary by therapist, client needs, and settings, typical individual sessions follow recognizable patterns.

Check-in (5-10 minutes): Sessions begin with brief verbal connection. The therapist asks about the client’s current state—how they’re feeling physically and emotionally, what’s been happening since last session, what they hope to address today. This isn’t extensive talk therapy but oriented checking-in that helps assess client’s window of tolerance for deeper work.

For trauma survivors, this check-in establishes safety and predictability. Knowing sessions start with this familiar ritual reduces anxiety about walking into unknown situations.

Art-making (25-40 minutes): The client creates art with materials they’ve chosen (or the therapist thoughtfully selected based on goals). The therapist might offer prompts (“Create an image representing how you’re feeling today” or “Make something that shows your safe place”) or the client might work self-directed.

During creation, the therapist observes but typically doesn’t interpret. Unlike psychoanalytic approaches where therapists might analyze artwork symbols, trauma-informed practice respects that meanings emerge from the creator, not external expert interpretation.

The therapist might ask gentle questions (“What’s happening with those colors?” or “Tell me about this part”) that invite reflection without imposing meaning. But often, the therapist simply witnesses—providing safe, non-judgmental presence while the client expresses through art.

This middle phase is where the therapeutic work happens. For some clients, the creative process itself—the meditation-like focus, the physical engagement, the decision-making—provides benefit before any meaning-making occurs. For others, what they create reveals insights, memories, or emotions previously inaccessible.

Reflection/Processing (10-15 minutes): After creation, therapist and client discuss the experience. This might include:

- What the client notices about their artwork

- What feelings emerged during creation

- What the artwork reveals or represents

- Connections to experiences outside the art room

- What was helpful or difficult about the process

The therapist helps the client make meaning but doesn’t impose interpretations. Questions like “What surprises you about this?” or “What would you title this piece?” invite client ownership of meaning.

For trauma processing work, this phase might include identifying what resources the client accessed, what felt manageable versus overwhelming, and how to apply insights to daily life.

Closure (5 minutes): Sessions end with grounding and transition preparation. This might include brief centering exercise, discussion of what client will do with the artwork created (take it home, leave it in the therapist’s care, photograph it, destroy it—all valid choices), and orienting to what’s next.

Trauma-informed practice pays particular attention to closure. Clients shouldn’t leave sessions in activated, destabilized states. If difficult content emerged, the therapist helps client return to regulated state before leaving—perhaps through breathing exercises, positive imagery, or physical grounding techniques.

Group sessions follow similar patterns but add dynamics of shared creation, witnessing others’ processes, and communal reflection. Groups offer powerful normalization—the recognition that “I’m not the only one struggling”—and opportunities to give and receive support.

The artwork created isn’t the point, though clients often treasure pieces as tangible evidence of their journey. The therapeutic value lives in the process: the safe exploration, the nonverbal expression, the regulation practiced, the meanings made, the agency experienced.

This process-over-product orientation distinguishes trauma-informed art therapy from art education (where skill development and aesthetic outcomes matter) and recreational art-making (where enjoyment is the goal). It’s therapy that happens through art, not art instruction with therapeutic benefits.

From the Margins to the Mainstream: Institutional Validation Fuels the Boom

The shift from “alternative therapy” to “evidence-based intervention” doesn’t happen through grassroots enthusiasm alone. Institutional adoption—by government, healthcare systems, schools, and corporations—transforms fields. For trauma-informed art therapy, that transformation accelerated dramatically between 2020 and 2026.

The White House Gets It: January 2024 Watershed Moment

On January 30, 2024, the White House Domestic Policy Council and National Endowment for the Arts co-hosted “Healing, Bridging, Thriving: A Summit on Arts and Culture in our Communities”—the first federal convening of its kind specifically addressing how arts contribute to health, wellbeing, and community vitality.

The significance wasn’t just symbolic. When the White House convenes a summit, it signals policy priority and channels resources, attention, and legitimacy.

Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy delivered a keynote discussing arts’ role in addressing the loneliness epidemic his office had identified as a major public health threat. His statement about music having effects he’d “seen in few medicines” as a practicing physician provided powerful validation from nation’s top health authority.

Attendees included Congressional representatives, federal agency leaders, mental health professionals, artists, advocates, academics, and art therapy leaders. Discussions ranged across how arts and culture contribute to mental health, invigorate communities, fuel democratic participation, and foster equity.

For the American Art Therapy Association president who attended, the summit transformed thinking about the field’s potential. Writing afterward, she reflected on opportunity for art therapists to assert their role and leadership in the broader arts-health movement—moving from responding specifically to mental health diagnoses toward supporting physical health and community wellbeing at population scales.

The summit led to expanded NEA funding for arts-health initiatives, new federal agency collaborations, and elevated discourse about “social prescription”—the practice of healthcare providers prescribing arts participation, nature exposure, or community engagement as treatment interventions.

This policy-level recognition matters for several practical reasons: It influences insurance coverage decisions, shapes medical school and nursing curricula, directs research funding, and signals to healthcare administrators that arts-based interventions merit investment.

Healthcare Integration: Hospitals, Clinics, and Recovery Centers

Major healthcare institutions have moved trauma-informed art therapy from nice-to-have amenities to core service offerings.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital employs behavioral health specialists who practice art therapy. Sophi Burch, who works there while pursuing her master’s degree in art therapy, exemplifies the growing pipeline of professionals entering hospital-based practice. Her undergraduate pre-art therapy certificate from University of Cincinnati prepared her for graduate training—a educational pathway that didn’t exist at scale a decade ago.

The United Kingdom’s National Health Service conducted one of the most rigorous studies of art therapy for healthcare worker wellbeing, publishing results in 2025. Researchers recruited 155 healthcare professionals across four London hospitals experiencing burnout and mental distress. Participants were randomized to immediate six-week art therapy groups or waitlist control.

Results showed statistically significant improvements in burnout scores and mental distress for those receiving art therapy compared to controls. The intervention, adapted from programs for oncology and palliative care doctors, incorporated trauma-informed methods developed specifically for supporting staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare administrators took notice—burned out staff leave, make mistakes, and drive up operating costs. Interventions that measurably reduce burnout while also improving wellbeing warrant investment.

Oncology and palliative care units increasingly integrate art therapy into comprehensive cancer care. Research documenting reduced emotional distress, decreased pain medication needs, and sometimes shorter hospital stays provides cost-effectiveness rationale that resonates with administrators focused on outcomes and expenses.

Rehabilitation centers for substance abuse, traumatic brain injury, and physical trauma have adopted art therapy based on evidence it supports recovery across cognitive, emotional, and motor domains. The embodied nature of creative work helps rebuild motor skills after injury. The emotional processing supports addiction recovery. The executive function required for planning and executing creative projects aids cognitive rehabilitation.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) launched arts-health initiatives in collaboration with hospitals, bringing visual art encounters to patients unable to visit museums. These programs, evaluated through research partnerships, contribute to growing evidence base while expanding access.

The World Health Organization has promoted arts-health integration globally, recognizing creative engagement as legitimate health intervention rather than merely enrichment activity. This international validation from the world’s most authoritative health body accelerates adoption in healthcare systems worldwide.

Schools Leading the Charge: Trauma-Informed Arts Education

While healthcare embraces art therapy for treatment, educational institutions increasingly adopt it for prevention and early intervention.

Following the Camp Fire and other disasters, Butte County’s model of deploying trauma-informed arts educators into schools demonstrated measurable benefits: improved student behavior, better attendance, enhanced academic performance. When COVID created universal trauma across student populations, the model proved broadly applicable.

Trauma-informed arts education differs from traditional art classes in several ways. Teachers receive training in recognizing trauma responses and creating emotionally safe environments. Curriculum emphasizes process over product, emotional expression over aesthetic achievement. Activities are designed to support regulation, build resilience, and provide non-threatening emotional outlets.

The Art of Education University developed extensive resources helping art teachers understand trauma’s impacts and implement trauma-informed approaches. Their guidance emphasizes that while art teachers aren’t therapists, they can create classroom conditions that support traumatized students’ learning and wellbeing.

Social-emotional learning (SEL) curricula now commonly integrate arts-based activities. Rather than viewing art as separate subject, schools recognize creative engagement as vehicle for teaching emotional regulation, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making—the core SEL competencies.

Research supports integration. Studies show students participating in regular arts programs—even without explicit therapeutic focus—demonstrate better social skills, higher self-esteem, improved emotional regulation, and enhanced academic performance compared to peers without arts access. When programs incorporate trauma-informed principles, benefits amplify.

Colleges and universities address student mental health crisis partly through arts-based programming. The Foundation for Art & Healing’s “Colors & Connection” workshops rolled out nationally on campuses specifically targeting 18-24 year-olds—identified as the loneliest demographic. The CreativityHub offers digital collection of creative activities designed to inspire connection.

This educational adoption matters because it provides early intervention before problems escalate to clinical severity. It normalizes creative expression as healthy coping mechanism. And it introduces millions of young people to healing arts approaches they might access later when facing trauma.

Corporate Wellness: The Untapped $60B Opportunity

Perhaps the most unexpected driver of trauma-informed art boom: corporations recognizing employee mental health as business imperative.

Global corporate spending on employee mental health and wellness programs will exceed $60 billion in 2025. Companies increasingly understand that stressed, burned-out employees are less productive, more likely to leave, take more sick days, and make more mistakes. The business case for wellbeing investment is clear.

Art therapy represents distinctive offering in competitive talent markets. While many companies offer traditional employee assistance programs with talk therapy access, creative wellness initiatives stand out as innovative, engaging, and aligned with values around whole-person support.

Tech companies—facing particular scrutiny about workplace stress and burnout—have been early adopters. Programs might include on-site art therapy sessions, creativity workshops, music rooms where employees can destress, or partnerships with museums offering art-based stress reduction.

Financial services firms, recognizing that market volatility and high-pressure environments affect trader and analyst mental health, implement art-based stress management. The approach offers private way to process work stress without formal mental health diagnosis.

Healthcare organizations addressing their own staff wellbeing increasingly include art therapy. The irony that healers often neglect their own health makes staff support programs particularly crucial, and the NHS study’s strong outcomes provide evidence for return on investment.

The American Art Therapy Association noted this corporate opportunity as particularly promising for field growth. Specialized corporate programs focusing on creative problem-solving and innovation mindset—not explicitly “therapy”—can command premium pricing while demonstrating measurable productivity gains.

Business models vary. Some companies hire staff art therapists. Others contract with providers for regular on-site workshops. Some partner with local art therapy clinics to provide employees subsidized or free access. The common thread: recognition that creative wellness interventions provide value worth paying for.

This corporate adoption simultaneously drives practitioner demand, raises public awareness, reduces stigma (“if Google offers art therapy, it must be legitimate”), and creates new revenue streams supporting field growth.

Who’s Seeking Healing Through Art? Stories from the Movement

Behind market statistics and institutional adoption live human beings discovering that creativity can facilitate healing they couldn’t find elsewhere. Their stories illuminate both why trauma-informed art resonates so powerfully and whom it serves.

Children Finding Their Voice: School-Based Programs

In Butte County classrooms, elementary students who survived the Camp Fire create artwork processing loss most adults struggle to articulate. One child draws her house—whole on one side, burned on the other. Another sculpts clay into twisted shapes representing how her stomach feels when she thinks about the fire. A third paints bright colors, explaining that’s what hope looks like.

These children aren’t receiving art instruction. They’re receiving trauma-informed intervention that uses art as medium for processing overwhelming experiences.

Research on children and art therapy during COVID-19 documented similar patterns globally. A randomized controlled trial in elementary schools found that students participating in emotion-based directed drawing showed reduced hyperactivity and improved emotional regulation compared to controls.

For children, art therapy offers particular advantages. Developmental stage matters—young children often lack vocabulary for complex emotions but can readily express through images. Even older children and adolescents sometimes find visual expression less threatening than verbal disclosure, especially when discussing experiences involving shame or betrayal.

The playful nature of art-making creates psychological safety. It’s “just making art,” not “doing therapy”—a distinction that helps anxious or resistant children engage. Once engaged in creative process, therapeutic work happens organically.

School-based programs reach children who might never access clinic-based therapy due to cost, transportation, or family resistance to mental health services. The universal access—all students participate, not just identified “problem” kids—reduces stigma.

Teachers report that students who engage in trauma-informed arts programming show improved classroom behavior, better peer relationships, increased willingness to try challenging academic tasks, and higher attendance. The creative outlet helps regulate nervous systems, reducing behavioral escalations that previously led to suspensions or special education referrals.

Veterans Confronting the Unspeakable: PTSD and Moral Injury

Combat trauma presents unique challenges for treatment. Veterans often describe their experiences as existing “beyond words”—not metaphorically but literally. The horror witnessed and perpetrated in war zones defies verbal articulation.

For these veterans, art therapy provides alternative pathway. Through painting, sculpture, music, or writing, they can begin expressing what they cannot say.

VA healthcare systems have substantially expanded art therapy offerings, recognizing evidence of effectiveness for combat-related PTSD. Programs report reduced symptom severity, improved emotional regulation, decreased substance use, better sleep, and enhanced social functioning.

One approach involves creating “trauma timelines”—visual representations showing events leading to, during, and after deployment. Veterans might use different colors for different emotional tones, symbolic imagery for specific events, or abstract shapes when words and realistic images both fail.

The distance art provides proves crucial. A veteran can create an image depicting “the soldier” rather than speaking as “I.” This third-person perspective allows engagement with traumatic content without full re-experiencing that might trigger overwhelming flashback states.

Moral injury—the anguish from perpetrating, witnessing, or failing to prevent acts that violate one’s moral code—particularly resists verbal therapy. The shame, self-condemnation, and spiritual anguish veterans experience often feels unspeakable.

Art offers container for these unbearable feelings. A marine who carries guilt for deaths under his command might create sculpture representing the weight he carries. An army medic who couldn’t save wounded comrades might paint images of darkness and light wrestling. These creative expressions don’t erase moral injury but provide way to externalize and examine feelings previously too painful to approach.

Group art therapy for veterans creates communities of understanding. Veterans often report that only others who’ve served in combat can truly understand their experiences. Creative groups provide peer support while avoiding competitive verbal dynamics that sometimes emerge in talk therapy groups.

Music therapy, particularly drumming circles, has shown strong outcomes with veteran populations. The rhythmic, physical nature helps discharge mobilized fight-flight energy. The ensemble coordination builds trust and cooperation. The sound itself can be cathartic release.

Domestic Violence Survivors Reclaiming Power

A mother-child art therapy program in domestic violence shelters demonstrates trauma-informed approaches for complex interpersonal trauma.

Research published in Child Abuse & Neglect studied programs in the United States and South Africa serving mothers and children exposed to intimate partner violence. These families face multiple traumas: the violence itself, often additional child maltreatment, poverty, displacement from homes, and disrupted attachment relationships.

The program used collaborative art-making—mothers and children creating together—to address both individual trauma and damaged relationships. Activities included creating family portraits, decorating boxes representing “safe places,” making emotion masks, and building “family trees” incorporating losses and hopes.

Outcomes showed improvements in both maternal mental health and child behavioral functioning. Perhaps most significantly, mother-child relationships strengthened—crucial finding since maternal mental health and secure attachment are primary protective factors for children exposed to intimate partner violence.

For the mothers, art provided safe expression when talking felt dangerous (shelters may have other residents who shouldn’t hear details) or simply impossible (shame, language barriers for immigrant survivors, traumatic amnesia for parts of experiences).

Creating art with their children helped mothers practice attuned presence and playful interaction—capacities often diminished by trauma’s effects. The collaborative process provided structure for positive interaction when parents feel overwhelmed or emotionally disconnected.

For children, seeing their mothers engage creatively modeled healthy coping. Creating together built sense of safety through shared experience. The artwork itself became tangible evidence that things can be beautiful despite pain.

Programs serving domestic violence survivors often incorporate elements of empowerment and reclaiming agency. An expressive mask-making activity might involve creating one mask representing how the survivor felt during abuse (powerless, invisible, fragmented) and another representing current or desired self (strong, whole, visible). The physical creation of different identity representations supports psychological process of moving from victim to survivor to thriver.

Healthcare Workers Processing Collective Trauma

The NHS study of art therapy for healthcare worker burnout revealed professionals desperate for support but unable to access traditional therapy due to time constraints, stigma concerns, or simply mental exhaustion that made more talking feel unbearable.

Six weekly 90-minute art therapy groups provided what months of encouragement to “practice self-care” hadn’t: actual relief.

Participants created artwork processing grief from patient deaths, moral distress from impossible triage decisions, anger at inadequate resources and systemic failures, fear of infecting family members, and bone-deep exhaustion that made even joyful activities feel burdensome.

The group format proved particularly valuable. Doctors, nurses, and other staff shared similar experiences, reducing the isolation that often accompanies healthcare work. Creating together built community and normalized struggling—counter to professional culture that often demands invulnerability.

Some participants created angry, dark artwork—slashing brushes across canvas, using ominous colors, depicting chaos and death. The permission to express these socially unacceptable feelings (healthcare workers are supposed to be compassionate helpers, not angry or despairing) provided psychological relief.

Others created beauty—flowers, landscapes, peaceful scenes—not denying difficulty but insisting that beauty still exists. This both-and capacity—holding pain and hope simultaneously—reflects psychological flexibility crucial for wellbeing.

The structured time for creative engagement meant staff actually did something restorative rather than just knowing they should. The accountability of weekly sessions overcame inertia that left self-care as perpetually delayed intention.

Post-program interviews revealed participants valued the tangible nature of creative work. Unlike their daily labor where outcomes often felt uncertain or inadequate, art-making produced visible results. They could point to something they created, evidence of agency and accomplishment.

Older Adults: Dementia, Loneliness, and Late-Life Healing

Art therapy for older adults addresses multiple concerns: cognitive decline, social isolation, late-life trauma processing, and meaning-making in final life stages.

Programs in memory care facilities report 40% reductions in behavioral incidents among residents with dementia who participate in regular art therapy. The cognitive stimulation supports remaining capacities. The sensory engagement provides grounding in present moment. The social interaction reduces isolation. The sense of accomplishment enhances dignity.

For individuals experiencing dementia’s frightening disorientation, creating art can provide islands of clarity and competence. Even when verbal abilities decline substantially, artistic expression often remains accessible. Residents who can no longer hold coherent conversations might paint vivid images or respond meaningfully to music.

Art therapy also addresses the loneliness epidemic particularly acute among older adults. The Foundation for Art & Healing has made this a central focus, recognizing that social isolation’s health impacts rival major diseases.

Group art activities create structured social interaction that feels purposeful rather than forced. Participants connect through shared creative experience, developing friendships around common interest. For older adults who’ve lost spouses, retired from careers, or relocated from familiar communities, these connections combat debilitating isolation.

Some older adults use art therapy to process lifetime of unaddressed trauma. A woman who experienced sexual abuse in childhood but never disclosed might, in her 70s, finally find capacity to explore these experiences through painting. An elderly veteran might engage with combat memories he’s suppressed for 50 years.

The safety of late life—no longer worrying about career impacts or family judgments, facing mortality that puts everything in perspective—sometimes creates windows for healing work previously impossible.

Intergenerational programs connecting older adults with children or young adults through collaborative art projects provide mutual benefits. Elders share wisdom and experience. Young people offer energy and hope. The creative collaboration builds relationships across divides.

These diverse applications—children, veterans, domestic violence survivors, healthcare workers, older adults—illustrate trauma-informed art therapy’s remarkable versatility and the human hunger for healing approaches that honor the whole person.

The Democratization of Healing: Technology, Access, and the DIY Movement

While institutional adoption drives much of the trauma-informed art boom, parallel developments in technology and self-guided resources are expanding access beyond formal therapy contexts.

Online Platforms Break Geographic Barriers

Virtual art therapy, barely existent before 2020, has become standard delivery mode for many practitioners and preferred option for many clients.

Research on virtual versus in-person effectiveness initially surprised even art therapy advocates. Studies comparing modalities for anxiety, depression, and some trauma applications found equivalent outcomes. The key: thoughtful adaptation to virtual format, not simply pointing camera at in-person session.

Effective virtual art therapy considers specific technical factors. Camera placement matters—clients need to show their artwork clearly to therapists. Lighting affects visibility. Internet stability impacts connection quality. Material selection emphasizes supplies clients can easily access at home.

Some adaptations enhance rather than diminish therapeutic value. Screen-sharing allows therapists and clients to collaboratively view reference images or therapeutic resources. Recording (with permission) lets clients revisit sessions or observe their creative process in ways not possible in person. Digital art-making—using tablets and styluses—offers some clients preferred medium, particularly those with motor limitations making physical painting difficult.

The geographic democratization proves profound. A trauma survivor in rural Montana can access a specialized art therapist trained in sexual assault trauma recovery who practices in Boston. An immigrant in Minnesota can work with a therapist who speaks their language and understands their cultural background, even if no such practitioner exists locally.

For people with mobility disabilities, chronic pain, or conditions making travel difficult, virtual sessions eliminate transportation barriers. Those with social anxiety sometimes engage more readily from home’s safety. Parents can participate without childcare challenges.

Online platforms have proliferated. Some connect clients with individual therapists for private sessions. Others offer group workshops on specific topics (grief, trauma recovery, stress management). Some provide courses combining recorded instruction with asynchronous creative assignments and periodic live sessions with instructors.

AR/VR: The Immersive Therapy Frontier

Augmented reality and virtual reality technologies represent art therapy’s cutting edge, with early research suggesting exciting possibilities.

AR tools allow users to create three-dimensional art in virtual space using hand gestures or controllers. For people with motor impairments limiting physical art-making, AR provides accessible alternative. The immersive quality creates strong sense of presence and engagement.

VR can combine creative expression with exposure therapy. A client might use VR to create safe virtual environment, then gradually add elements representing traumatic situations—building tolerance through controlled, creative exposure.

Early studies show promise but VR art therapy remains emerging field. Technology costs limit accessibility. Not all clients tolerate VR (some experience motion sickness or find immersion overwhelming). Therapists need training in technology use alongside clinical skills.

Still, particularly for younger generations comfortable with digital environments, VR may offer engaging pathway into therapeutic work that feels natural rather than clinical.

Self-Guided Resources: Healing Without a Therapist?

The Foundation for Art & Healing’s CreativityHub exemplifies growing provision of self-guided creative wellness resources. This digital collection offers 12+ creative activities designed to inspire connection and support mental health.

During pandemic lockdowns, the Quarantine Family Toolkit provided parents with art activities, mindfulness practices, and guidance on talking with children about COVID-19—all accessible without professional facilitation.

YouTube hosts countless channels offering guided meditation combined with art-making, tutorials on using creativity for stress relief, and process-focused art activities explicitly framed as therapeutic.

Apps like Calm and Headspace have added creative components to meditation offerings. Adult coloring book phenomenon reflects widespread recognition that creative engagement reduces stress.

These self-guided approaches serve important functions. They provide low-cost access for people who can’t afford therapy. They reduce stigma by framing creative wellness as normal health practice rather than clinical intervention. They offer immediate access without waiting lists. They allow privacy for those uncomfortable with disclosure.

Important limitations exist, however. Self-guided resources work well for general stress management, mild-to-moderate anxiety, and building resilience. They don’t replace professional treatment for trauma, severe depression, PTSD, or other clinical conditions.

The risk: individuals with serious mental health needs might rely on DIY approaches when professional help is necessary. Self-help can delay appropriate treatment or leave people struggling with symptoms that effective therapy could significantly improve.

Best practice involves informed discernment. For everyday stress, creative self-care makes sense. For persistent distress, sleep problems, relationship difficulties, or trauma symptoms, professional assessment is warranted. Many people benefit from both—therapy for clinical issues, self-guided creativity for ongoing wellness.

The Equity Question: Who Still Can’t Access Healing Arts?

Despite technology and institutional expansion, access barriers persist—creating equity concerns the field increasingly recognizes must be addressed.

Cost remains primary barrier. Art therapy typically costs $100-$200 per session. For low-income individuals and families, this represents insurmountable expense. Insurance coverage remains inconsistent. While some plans cover art therapy, many don’t or require extensive documentation and prior authorization that create administrative burden.

The practitioner shortage disproportionately affects rural and low-income urban areas. Certified art therapists cluster in affluent suburbs and metropolitan centers. Rural residents may live hours from nearest practitioner. Low-income urban neighborhoods often lack services despite high need.

Virtual therapy helps but doesn’t fully solve geographic inequity—it requires technology and internet access that digital divide leaves many without. During pandemic, these gaps became brutally apparent when students couldn’t access online school and workers couldn’t shift to remote work.

Cultural barriers matter too. Current art therapy practice reflects primarily Western theoretical frameworks and cultural assumptions. Training programs are beginning to emphasize cultural humility and anti-oppressive practices, but the field has work to do in truly honoring diverse healing traditions and cultural expressions.

Some cultural communities view mental health treatment with suspicion, stemming from historical trauma (psychiatric abuse in prisons and institutions) or cultural values around privacy and family-centered rather than individual problem-solving. Art therapy’s Western framing may not resonate.

Language barriers exclude non-English speakers in many regions. While art’s nonverbal nature theoretically transcends language, therapeutic relationship still requires communication, and interpreter availability remains limited.

Disability access creates another equity dimension. While art therapy can be highly accessible for many disabilities, physical spaces aren’t always wheelchair accessible, materials may not accommodate visual or motor impairments, and not all practitioners have training in disability-specific adaptations.

The Prebys Foundation’s $5.2 million initiative specifically targets underserved communities, recognizing that market forces alone won’t ensure equitable access. Many programs offer sliding scale fees. Community mental health centers integrate art therapy into services for low-income populations. Schools provide universal access regardless of family income.