In 1793, something revolutionary happened in Paris. For the first time in history, ordinary citizens walked through the halls of the Louvre—not as servants or supplicants, but as equals viewing art that once belonged exclusively to French royalty. This single moment symbolizes one of history’s most profound cultural transformations: the evolution of museums from private treasure hoards into public educational institutions accessible to all.

But how did this radical shift occur? What philosophical, political, and social forces transformed collecting from an aristocratic hobby into a democratic right?

This comprehensive guide traces the fascinating journey of museums from ancient collecting traditions through Renaissance cabinets of curiosities to Enlightenment public institutions and today’s debates over digital access, colonial legacy, and social justice. Drawing on museum studies scholarship, institutional archives, and contemporary research, we’ll explore not just what changed, but why—revealing the power dynamics, cultural forces, and revolutionary ideas that democratized access to humanity’s cultural heritage.

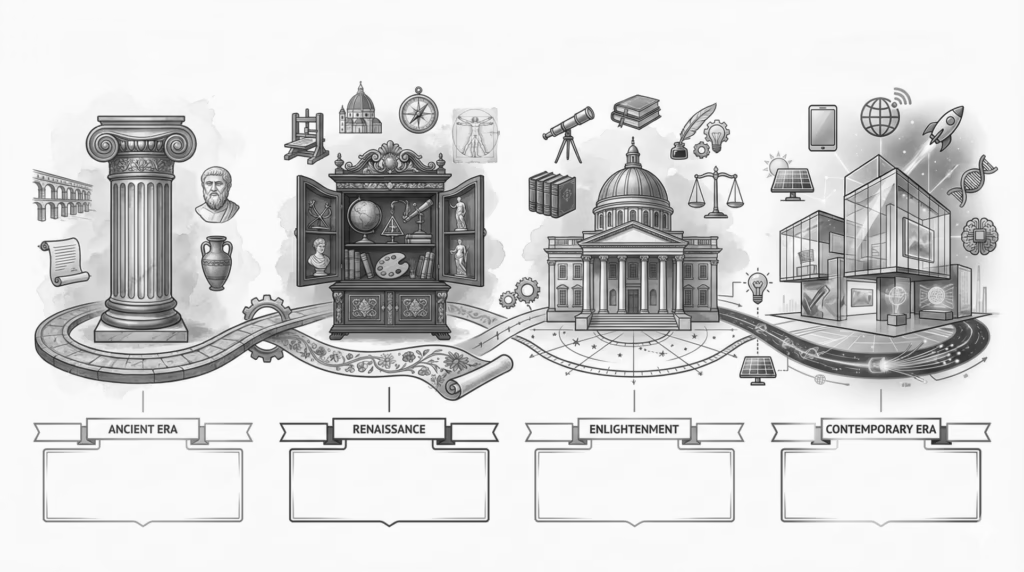

Understanding Museum Evolution: A Visual Timeline Overview

Before diving into the detailed history, let’s establish the big picture. Museum evolution wasn’t a smooth linear progression but rather a series of dramatic shifts driven by changing worldviews, political revolutions, and social movements.

The Three Revolutionary Shifts

The transformation from private collecting to public museums involved three fundamental changes:

Shift 1: Wonder → Reason (Renaissance to Enlightenment) During the Renaissance, collectors assembled cabinets of curiosities that mixed authentic specimens with fabricated marvels, organized by rarity and wonder rather than scientific classification. The Enlightenment replaced this approach with rational categorization, empirical study, and systematic knowledge. Collections shifted from entertaining elite guests to educating the public.

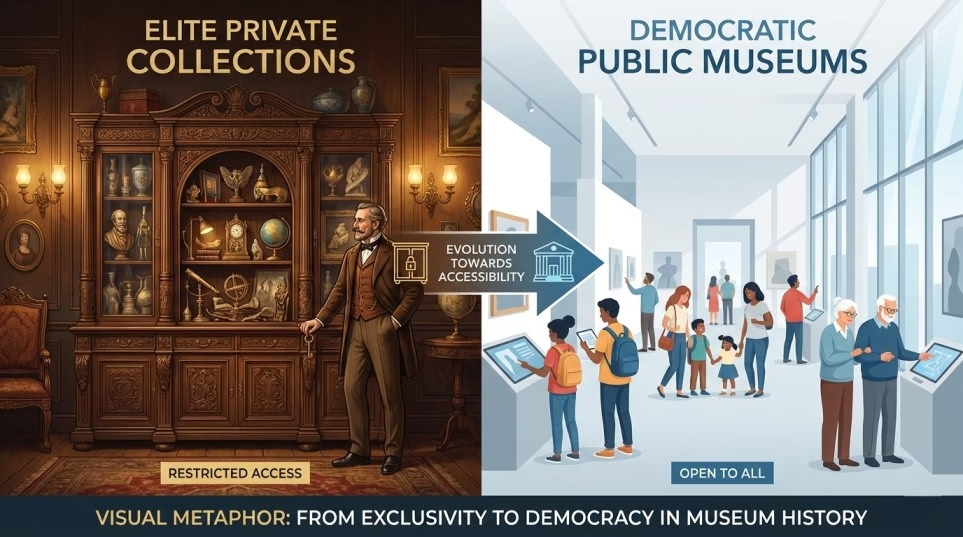

Shift 2: Private → Public (17th-18th Centuries) The most dramatic transformation occurred when private collections became public institutions. What began with the Ashmolean Museum in 1683—requiring written applications and entrance fees—culminated with the Louvre in 1793, declared free and open to all French citizens. This shift reflected Enlightenment belief that knowledge shouldn’t be monopolized by aristocrats but shared for the public good.

Shift 3: Elite → Democratic (19th-21st Centuries) Early “public” museums remained socially exclusive through entrance fees, restricted hours coinciding with working-class labor, and cultural gatekeeping. True democratization required centuries of gradual expansion: eliminating fees, extending hours, simplifying labels, creating educational programs, and ultimately confronting whose stories museums tell and who feels welcomed.

These shifts matter because they reveal museums aren’t neutral spaces but institutions shaped by—and shaping—ideas about knowledge, power, and who deserves access to culture.

Quick Reference Timeline: Major Milestones

Ancient Era (Prehistoric – 400s CE)

- Prehistoric cave art as communal display

- Greek mouseion (shrines to the Muses, scholarly study)

- Aristotle’s systematic collection (340s BCE)

- Library of Alexandria’s Mouseion (~280 BCE)

- Roman public sculpture displays and private Pinakothecae

Private Collecting Era (1400s – 1700s)

- Princess Ennigaldi’s labeled collection (530 BCE, Babylon)

- Renaissance revival of collecting (Medici, 1400s)

- Cabinets of curiosities spread across Europe (1500s-1700s)

- Famous wunderkammer: Ole Worm, Rudolf II, Athanasius Kircher

Birth of Public Museums (1683 – 1793)

- Ashmolean Museum opens (1683, Oxford)

- British Museum established (1753, London)

- Uffizi Gallery opens to public (1769, Florence)

- French Revolution creates Louvre as public museum (1793, Paris)

Museum Proliferation Era (1800s)

- Nationalist museum movements across Europe

- Colonial expansion fills collections

- Museum specialization (art, natural history, science)

- American museums founded by private philanthropy (1870s-1890s)

Professionalization & Democratization (1900s)

- Curatorial profession emerges

- Museum education departments created

- World wars threaten and transform collections

- Critical museum studies questions authority

- Repatriation movements begin (1990s)

Digital Transformation (2000s – Present)

- Online collections and virtual tours

- Social media engagement

- COVID-19 accelerates digital shift

- Decolonization and repatriation debates intensify

- Museums confront social justice role

Ancient Roots: Collecting Before Museums (Prehistory – 1400s CE)

Museums didn’t emerge from nowhere. Humans have always collected, displayed, and treasured objects. Understanding these ancient precedents reveals what’s timeless about museum impulses—and what’s revolutionary about modern public institutions.

Early Human Collecting Instincts

The caves of Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain contain some of humanity’s earliest “exhibitions”—prehistoric paintings created 15,000-30,000 years ago. These weren’t museums in any modern sense, but they demonstrate fundamental human urges: to create, display, and share visual culture within community spaces.

Cave art likely served multiple functions: religious ritual, storytelling, education, or simply aesthetic expression. What matters for museum history is that these were communal displays accessible to community members, creating shared visual experiences that reinforced group identity.

This contrasts sharply with later private collecting, where access was restricted and collections symbolized individual prestige rather than community bonds.

The Greek Mouseion and Library of Alexandria

The English word “museum” derives from the Greek mouseion (Μουσεῖον), meaning “seat of the Muses”—the nine goddesses who patronized arts and sciences in Greek mythology. Originally, mouseion referred to shrines dedicated to these deities, places for worship rather than study.

The philosopher Aristotle transformed this concept in the 340s BCE. Traveling to the island of Lesbos with his student Theophrastus, Aristotle collected and classified botanical specimens, establishing foundations for empirical methodology. This systematic collection—organized for research rather than worship or wonder—represents a crucial precedent for modern museums.

Aristotle’s philosophical school in Athens, the Lyceum, included a mouseion housing his collection of natural history specimens. For the first time, objects were assembled not for religious devotion or social prestige but for advancing knowledge through systematic study.

The most famous ancient mouseion was part of the Library of Alexandria, founded around 280 BCE by Ptolemy Soter. This institution combined a massive book collection with a community of scholars who conducted research, making it simultaneously a library, research institute, and early museum. Though primarily focused on texts, the Alexandrian Mouseion likely included specimens and artifacts used in scholarly work.

Roman Collecting and Display

Rome’s imperial expansion brought unprecedented influxes of art, particularly Greek sculptures looted from conquered territories. These artworks appeared everywhere in Rome—decorating public forums, temples, and civic buildings. Art historian Jerome Pollitt famously observed that “Rome became a museum of Greek art.”

This marked a significant shift: art displayed for purely decorative and aesthetic purposes, separated from its original religious or civic context. Romans appreciated Greek sculptures as beautiful objects worth displaying, not as sacred items or functional civic monuments. This “musealizing” impulse—taking objects out of original context and viewing them as art—foreshadows modern museum practice.

Wealthy Romans also created private Pinakothecae (picture galleries) within their homes. These rooms, filled with paintings or painted walls, were technically private but accessible to the owner’s social circle. Through a Pinakotheke, Romans displayed cultural sophistication and accumulated social prestige.

Importantly, these weren’t public in any democratic sense. Visitors needed social connections or aristocratic status to gain entry. The collection served the owner’s reputation, not public education.

Non-Western Collecting Traditions (Often Overlooked)

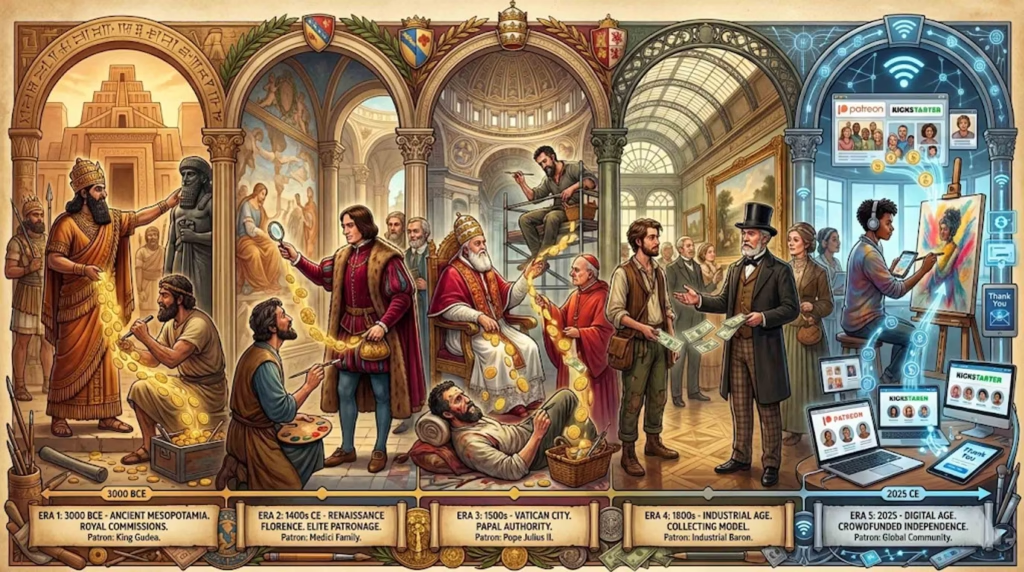

Museum history is typically told as a European story, but collecting and cultural preservation occurred globally.

Princess Ennigaldi’s Museum (Babylon, 530 BCE) may be the world’s oldest known museum. Discovered in 1925 by archaeologist Leonard Woolley in the ruins of King Nabonidus’s palace, this collection contained artifacts spanning 1,500 years of Mesopotamian history—ancient even to ancient Babylonians. Objects were systematically organized with labels noting their provenance, demonstrating sophisticated curatorial thinking.

Chinese Imperial Collections preserved jade, bronze vessels, calligraphy, and paintings for centuries. These collections served multiple purposes: demonstrating the emperor’s cultural refinement, preserving historical continuity, and legitimizing dynastic authority through connection to the past.

Islamic Scholarly Collections, particularly the House of Wisdom in Baghdad (9th century), assembled manuscripts, scientific instruments, and specimens. These institutions combined library functions with systematic knowledge collection, supporting translation projects and scientific advancement.

African Cultural Preservation included royal regalia protection, sacred object guardianship, and oral history maintenance. While different in form from European collecting, these practices served similar functions: preserving cultural heritage and transmitting knowledge across generations.

Recognizing these non-Western traditions is crucial because it challenges the narrative that museums are uniquely European inventions. Cultural preservation is universal; what’s distinctive about European museum development is how colonialism disrupted non-Western collecting practices while simultaneously filling European museums with artifacts from colonized territories.

The Cabinet of Curiosities Era: Private Wonder Rooms (1400s-1700s)

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, a distinctive collecting phenomenon emerged across Europe: the cabinet of curiosities, known in German as Wunderkammer (wonder room) or Kunstkammer (art room). These private collections represented the immediate predecessors to modern museums and reveal both continuities and profound differences.

What Was a Cabinet of Curiosities?

A cabinet of curiosities was simultaneously a physical space and a conceptual framework. Initially, “cabinet” meant an entire room dedicated to displaying collections. Later, the term also described elaborate pieces of furniture—often with multiple drawers, secret compartments, and ornate decoration—designed to store and dramatically reveal rare objects.

These collections served multiple purposes:

Demonstrating Renaissance Learning: During the Renaissance, the ideal of the “Renaissance man” meant pursuing knowledge across multiple disciplines. A well-stocked cabinet proved the owner’s intellectual breadth, showing familiarity with natural philosophy, classical antiquity, world geography, and artistic taste.

Accumulating Social Capital: Cabinets functioned as entertainment for elite social circles. Owners invited aristocrats, scholars, and dignitaries to view their collections, using rare objects as conversation pieces. The more unusual and impressive the collection, the greater the owner’s prestige.

Controlling the World in Miniature: Cabinets aspired to encyclopedic completeness, recreating the entire world within a single room. This “microcosm of the macrocosm” reflected Renaissance humanist belief in human ability to master and order knowledge.

Creating Wonder and Astonishment: Unlike modern museums emphasizing education, cabinets prioritized wonder—the emotional response to encountering the rare, strange, and marvelous. Objects were chosen to provoke amazement, not necessarily to advance understanding.

The Four Categories of Objects

Renaissance collectors organized cabinets around four categories, using Latin taxonomy:

Naturalia – Products of Nature Natural specimens including fossils, minerals, shells, coral, taxidermied animals, skeletons, and dried plants. Particularly prized were “monsters”—two-headed animals, deformed specimens, or unusual creatures. Stuffed crocodiles, suspended from ceilings, became cabinet status symbols.

Preservation was rudimentary. Collectors favored items that dried easily or could undergo primitive taxidermy. More delicate specimens were often lost, so collections skewed toward durable materials like shells and bones.

Artificialia – Human-Made Objects Artwork, ancient coins and medals, sculpture, scientific instruments, clocks, and automatons. This category demonstrated human creativity and technical skill. Renaissance artisans created objects specifically for cabinets, like elaborately carved ivory or engraved nautilus shells, deliberately blurring boundaries between natural beauty and human craft.

Exotica – Objects from Distant Lands The Age of Exploration (late 1400s-1600s) brought European collectors unprecedented access to objects from Africa, Asia, and the Americas. These “exotic” items—Indigenous textiles, weapons, ceremonial objects, and natural specimens from distant lands—represented the expanding known world.

Tragically, this category often included items acquired through colonial violence, setting a pattern that would intensify when cabinets evolved into museums.

Scientifica – Testaments to Human Mastery of Nature Scientific and technological objects including astrolabes, telescopes, microscopes, clocks, and automatons. These demonstrated humanity’s ability to measure, understand, and control natural forces—a key Renaissance and Enlightenment theme.

The organization principle wasn’t scientific classification but wonder. A two-headed calf might sit beside ancient Roman coins, with no connection except both being rare. This eclectic arrangement reflected pre-Enlightenment worldviews where mystical connections linked disparate objects.

Famous Cabinets and Their Creators

Ole Worm’s Cabinet (Copenhagen, 1600s) Danish physician and naturalist Ole Worm (Latinized as Olaus Wormius) created one of the most famous cabinets, illustrated in a widely circulated 1655 engraving. His collection mixed natural history specimens with ethnographic objects, emphasizing systematic study alongside wonder. Worm’s cabinet influenced both continued wunderkammer tradition and emerging scientific museums.

Rudolf II’s Kunstkammer (Prague, late 1500s-early 1600s) Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II assembled perhaps the most magnificent cabinet, containing thousands of objects: paintings, sculptures, scientific instruments, natural specimens, and mechanical marvels. His collection served explicitly political purposes—demonstrating imperial power, cultural sophistication, and divine favor. Court artists created works specifically for the Kunstkammer, turning it into both collection and creative workshop.

Medici Studiolo (Florence, 1570s) Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici’s studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio exemplified Italian cabinets. This small, richly decorated room with hidden compartments and drawers created theatrical revelation—each opened drawer revealed new wonders. The studiolo was simultaneously office, laboratory, hiding place, and cabinet of curiosities.

Athanasius Kircher’s Museum (Rome, 1650s-1680s) Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher’s collection in the Roman College became a significant attraction. Kircher pursued encyclopedic knowledge across disciplines—Egyptology, geology, magnetism, music theory—and his museum reflected this breadth. His approach balanced wonder with emerging scientific methodology, making his collection influential for later museum development.

Who Could See Cabinets?

This is a crucial question because it reveals the fundamental difference between cabinets and public museums: access.

Cabinets were emphatically not public. Viewing required:

Social Connection: Owners invited guests from their social circle—fellow aristocrats, scholars, merchants, visiting dignitaries. You needed to know someone who knew someone.

Cultural Capital: Even if invited, visitors needed education to appreciate and discuss the collection. Visiting a cabinet was a performance of erudition where guests demonstrated knowledge by identifying objects and understanding references.

Economic Resources: Only wealthy individuals could assemble significant collections. Trading networks, colonial connections, and purchasing power determined collection quality.

Time and Leisure: Both collecting and visiting required leisure time—a luxury of aristocratic and wealthy merchant classes, not peasants or laborers.

Some cabinets were “semi-public”—open to educated visitors who applied, perhaps paying a small fee. But “public” here meant “educated elite,” not anything approaching democratic access. The vast majority of people would never see a cabinet of curiosities.

The Worldview Behind Cabinets

Understanding Renaissance worldviews helps explain why cabinets were organized so differently from modern museums.

Hermetic Philosophy and the Great Chain of Being: Renaissance thinkers inherited medieval beliefs in hidden connections linking all creation. The “doctrine of signatures” held that herbs resembling body parts cured ailments of those parts. The “great chain of being” described hierarchical connections from God down through angels, humans, animals, plants, to minerals. Cabinets reflected these beliefs, with arrangements suggesting mystical correspondences between objects.

Theater of Memory: Renaissance memory techniques organized knowledge spatially. Collectors used physical arrangements to encode relationships and aid recall. The cabinet itself became a memory system where walking through triggered associations and retrieved information.

Wonder as Knowledge: Before Enlightenment empiricism, wonder was considered a valid path to understanding. Encountering the marvelous prompted contemplation of divine creation and nature’s mysteries. Cabinets deliberately created wonder-inducing juxtapositions.

Pre-Scientific Classification: Carolus Linnaeus’s systematic biological taxonomy (1735) postdated most cabinets. Earlier collectors lacked standardized classification schemes, organizing by personal logic, aesthetic appeal, or mystical association.

These worldviews shaped not just what collectors gathered but how they understood their collections’ meaning and purpose.

The Enlightenment Revolution: Birth of Public Museums (1650s-1790s)

The transformation from private cabinets to public museums represents one of the most profound shifts in cultural history. This wasn’t merely about opening doors—it reflected revolutionary changes in how Europeans understood knowledge, education, power, and citizenship.

Enlightenment Values and the Public Good

The Enlightenment (roughly 1650s-1800s) challenged traditional authority structures through several interconnected principles:

Reason Over Tradition: Enlightenment thinkers argued that knowledge should derive from observation and logic rather than inherited belief or religious authority. This empirical approach demanded systematic study of nature and human societies.

Individual Rights and Liberty: Philosophers like John Locke argued humans possessed natural rights including life, liberty, and property. These ideas challenged aristocratic privilege and absolute monarchy.

Education and Progress: Enlightenment ideology held that human society improved through education. Widespread access to knowledge would produce rational citizens capable of self-governance.

Public Good Over Private Privilege: Knowledge shouldn’t be monopolized by elites but shared for collective benefit. Public education, libraries, and museums could elevate entire societies.

Democratic Implications: Though most Enlightenment thinkers weren’t full democrats, their logic pointed toward broader political participation. If reason rather than birth determines wisdom, then governance shouldn’t be restricted to aristocrats.

These principles directly challenged cabinet of curiosities logic. If knowledge serves private prestige and entertainment, it violates the public good. If collections advance understanding, they should be accessible to scholars and citizens, not hidden in aristocratic homes.

Philosopher Francis Bacon explicitly criticized cabinets as “frivolous impostures for pleasure and strangeness,” contrasting them with systematic scientific collections that advanced human knowledge.

This philosophical shift created the intellectual foundation for public museums.

The Ashmolean Museum (1683): First Purpose-Built Public Museum

The Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University represents a crucial transition point. Though far from fully democratic, it established the public museum model.

Origin Story: Naturalist John Tradescant (1570-1638) assembled an extensive collection of artifacts and natural specimens through his travels and connections. After financial difficulties, Tradescant’s collection passed to Elias Ashmole, who added his own substantial holdings. In 1675, Ashmole donated the entire collection to Oxford University, which built a dedicated structure to house it.

Revolutionary Features:

Dedicated Building: Unlike cabinets squeezed into existing spaces, the Ashmolean occupied a building designed specifically for collections, with proper storage, display areas, and even a laboratory for scientific research.

Institutional Ownership: The collection belonged to Oxford University, not an individual. This meant institutional continuity, professional management, and educational mission.

Public Access: The Ashmolean accepted visitors—a revolutionary concept. However, access was heavily restricted: visitors paid an entrance fee, entered one at a time, and were guided through by a keeper. Working-class people were effectively excluded by fees and cultural expectations.

Rational Organization: Unlike eclectic cabinets, the Ashmolean organized collections systematically to support research and teaching. Natural history specimens were classified scientifically; archaeological artifacts grouped culturally and chronologically.

Educational Mission: Ashmole specified the collection should support practical research and education, explicitly linking collections with learning.

The Ashmolean’s significance lies not in perfect democratic access but in establishing the template: institutional ownership, public accessibility, rational organization, and educational purpose.

British Museum (1753): Universal Knowledge for the Nation

The British Museum took the public museum concept further, establishing it on a national scale.

Origin: Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), physician and naturalist, assembled an enormous collection—over 71,000 objects including natural specimens, books, manuscripts, medals, and antiquities. On his death, Sloane offered the collection to the British nation for £20,000 (far below market value). Parliament accepted, also acquiring two major library collections, and passed the British Museum Act in 1753.

Revolutionary Significance:

Parliamentary Creation: Unlike private donations, the British Museum was established by government act, making it explicitly public and national from inception.

Free Access: The museum charged no admission—radical for the era. However, “free” didn’t mean open. Initial access required written applications submitted weeks in advance, with small groups admitted at specific times under keeper supervision. The process mimicked court protocols, excluding working-class people despite no monetary barrier.

Enlightenment Mission: The museum’s founding charter emphasized making collections available for “learned and curious persons,” embodying Enlightenment ideals about public knowledge advancing society.

Universal Scope: Rather than specialized focus, the British Museum aspired to encyclopedic coverage—natural history, antiquities, manuscripts from around the world. This “universal museum” concept would become influential but also controversial.

Evolution and Expansion: Throughout the 1800s, the British Museum’s collections exploded through imperial expansion. Major acquisitions included:

- The Rosetta Stone (1802), key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, acquired after Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign

- The Parthenon Sculptures (1816), removed from Athens by Lord Elgin—still controversial today

- Assyrian sculptures (1840s onward) from Mesopotamian excavations

- Benin Bronzes (1897), looted during British military expedition

This growth pattern reveals how closely museums tied to colonialism—a legacy still haunting institutions today.

Other Early Public Museums

The British Museum wasn’t alone. Across 18th-century Europe, private collections transformed into public institutions:

Capitoline Museums (Rome, opened to public 1734) The Capitoline actually began in 1471 when Pope Sixtus IV donated ancient sculptures to “the people of Rome.” However, full public access only came in 1734. This demonstrates the long gap between nominal public ownership and actual accessibility.

Uffizi Gallery (Florence, public access 1769) The Medici family’s spectacular art collection, accumulated over centuries, was bequeathed to Tuscany in 1743 “for the people of Tuscany and all nations.” Public access formalized in 1769 under Grand Duke Peter Leopold, though initially restricted to educated visitors.

Museum Fridericianum (Kassel, 1779) This German museum represents “enlightened absolutism”—monarchs embracing Enlightenment ideas while maintaining autocratic power. Landgrave Frederick II created a public museum demonstrating progressive values while reinforcing princely prestige.

Common Patterns:

These early public museums shared characteristics:

- Transformation of existing aristocratic/royal collections

- Architecture emphasizing grandeur and cultural authority

- Restricted access despite “public” designation (application processes, entrance fees, limited hours)

- Educational rhetoric (“improving the public”) mixed with elite cultural gatekeeping

- Collections reflecting imperial power and colonial acquisition

The French Revolution and the Louvre (1793)

Perhaps the single most important moment in museum history occurred on August 10, 1793, when the French Revolutionary government opened the Louvre as the Musée Français.

Background: The Louvre had been a royal palace since the 16th century. Under Louis XIV, parts became an art gallery displaying royal collections. When Louis XIV moved to Versailles, proposals emerged to convert the Louvre into a public museum—but they remained unrealized until revolution made them possible.

Revolutionary Transformation:

Political Symbolism: Opening the Louvre wasn’t just cultural policy—it was revolutionary theater. Making royal treasures public property symbolized the people’s triumph over monarchy. What had belonged to kings now belonged to citizens.

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité Embodied:

- Liberté (Liberty): Free admission removed economic barriers

- Égalité (Equality): All citizens equal before art, regardless of birth

- Fraternité (Brotherhood): Shared national heritage binding citizens together

Truly Public and Free: Unlike the British Museum’s restrictive access, the Louvre opened widely and without charge. Ordinary Parisians walked halls previously reserved for royalty—a powerful experience of revolutionary democracy.

National Patrimony: The National Committee declared the museum “property of the people of France; a monument to the glory of the French nation and its history.” Museums became explicitly national institutions representing collective identity and pride.

Educational Mission: Revolutionary ideology saw the Louvre as educational, “civilizing” citizens by exposing them to great art. This paternalistic view—that proper art improves people morally—would influence museums for two centuries.

International Impact: The Louvre model inspired nationalist museum movements across Europe. Every self-respecting nation needed an impressive public museum to demonstrate cultural sophistication and historical legitimacy.

However, the Louvre also expanded through Napoleonic conquest, acquiring masterpieces from Italy, Belgium, and elsewhere—some returned after Napoleon’s defeat, some retained. This revealed how museums served not just education but imperial power projection.

What Actually Changed in the Enlightenment Shift?

Comparing cabinets of curiosities with Enlightenment public museums reveals profound transformations:

Purpose

- Cabinets: Private prestige, elite entertainment, wonder

- Public Museums: Education, national pride, systematic knowledge

Access

- Cabinets: Invitation-only, social circle of owner

- Public Museums: Theoretically open (though class barriers remained)

Funding

- Cabinets: Personal wealth of collector

- Public Museums: State funding or institutional endowments

Organization

- Cabinets: Eclectic, emphasizing rarity and wonder

- Public Museums: Rational classification by scientific/historical principles

Authority

- Cabinets: Owner’s personal taste and knowledge

- Public Museums: Curatorial expertise, scholarly standards

Collections

- Cabinets: Naturalia, artificialia, exotica, scientifica mixed freely

- Public Museums: Specialized by discipline (art, natural history, archaeology)

Worldview

- Cabinets: Pre-scientific, mystical connections, wonder-based

- Public Museums: Enlightenment rationality, empirical classification, educational

This comparison shows why the Enlightenment transformation was genuinely revolutionary—it wasn’t just about who could enter but about fundamentally reimagining collections’ purpose and meaning.

Museums and Nationalism: The 19th Century Explosion (1800-1900)

The 1800s witnessed unprecedented museum proliferation across Europe and America. Museums became essential nation-building tools, civilizing missions, and repositories for imperial spoils—setting patterns that continue shaping institutions today.

Why Museums Mattered for Nation-States

After the Napoleonic Wars, Europe’s political map was redrawn. Emerging nations needed symbols of identity, historical legitimacy, and cultural sophistication. Museums answered all three needs.

National Identity Formation: Museums created shared heritage. By displaying “our” art, “our” history, “our” antiquities, museums fostered collective identity transcending local or regional attachments. French, German, Italian, Spanish national museums helped forge citizens from diverse populations.

Historical Legitimacy: New nations needed to prove they deserved sovereignty. Museums demonstrated historical continuity: “We possess these ancient artifacts; therefore, we are an ancient, legitimate nation.” This explains why nations competed to acquire archaeological treasures—each piece strengthened claims to historical importance.

Cultural Sophistication: In European power hierarchies, cultural achievement mattered alongside military and economic might. Impressive museums signaled a nation belonged among “civilized” powers. This competitive dynamic drove museum proliferation—every capital needed collections rivaling London, Paris, or Berlin.

Unifying Diverse Populations: Museums promoted national unity by emphasizing shared heritage over local differences. Regional distinctions were downplayed while “national” characteristics were highlighted.

Major nationalist museums included:

- Prado (Madrid, opened 1819): Spanish royal collection nationalized

- Altes Museum (Berlin, 1830): Prussian cultural ambition

- Hermitage (St. Petersburg, public opening 1852): Russian imperial grandeur

- National Gallery (London, 1838): British cultural leadership

- National Museum (Copenhagen, 1849): Danish national awakening

Museums as Civilizing Missions

Victorian-era Europeans believed exposure to “great art” morally improved viewers. Museums thus became tools for civilizing the masses—particularly the expanding industrial working class.

Moral Improvement Through Art: Prevailing ideology held that contemplating beautiful or morally uplifting art refined character. Museums could transform rough laborers into cultivated citizens through aesthetic education.

Alternative to “Low” Entertainment: Museum advocates positioned institutions as wholesome alternatives to pubs, music halls, and other working-class entertainments deemed corrupting. As anthropologist Franz Boas stated in 1907, museum visits “counteract the influence of a saloon and of the race-track.”

Architectural Reinforcement: Museum buildings themselves communicated these messages. Neoclassical architecture—Greek and Roman-inspired temples—created reverent atmospheres. Grand stairs, imposing columns, and solemn interiors signaled this was sacred space for cultural elevation, not casual entertainment.

Social Control: Museums weren’t just about enlightenment—they also shaped behavior. Architectural design controlled visitor movement; rules mandated quiet contemplation; dress codes excluded the poorest. Thomas Greenwood’s 1888 proclamation that museums were “as indispensable for municipalities as drainage, the police and lunatic asylums” reveals how museums were understood as social management tools.

Limited Actual Access: Despite rhetoric about improving the masses, practical barriers excluded working-class people: museums opened during work hours, required proper attire, and maintained intimidating formality. “Public” museums often served middle and upper classes.

Colonial Expansion and Museum Collections

The 19th century saw European imperial expansion reach its peak. Museums filled with artifacts from colonized territories, creating collections that remain controversial today.

How Collections Grew:

Archaeological Excavations: European archaeologists excavated sites throughout colonized regions—Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Turkey, China. Finds were shipped to European museums, ostensibly for preservation and study but effectively removing cultural property from origin countries.

“Gifts” from Colonial Administrators: Objects acquired by colonial officials—through purchase, confiscation, or unclear circumstances—entered museum collections. The line between legitimate acquisition and coercion was often blurry.

Military Looting: Some acquisitions were straightforward theft. The 1897 British punitive expedition against Benin City (in modern Nigeria) resulted in the looting of thousands of bronze sculptures and ivory pieces, now distributed across Western museums. This wasn’t archaeology—it was plunder.

Problematic Displays:

Ethnographic Museums: European museums created “ethnographic” displays showing cultures from colonized territories. These exhibits often:

- Portrayed non-European cultures as “primitive” or “savage”

- Arranged displays showing evolutionary progression from “barbarism” to “civilization” (with European culture as the endpoint)

- Displayed sacred objects or human remains without consent

- Reinforced racist hierarchies justifying colonial domination

“Universal Museum” Ideology: Major museums like the British Museum, Louvre, and Berlin Museum claimed to preserve “universal heritage” for all humanity. This supposedly benevolent framing obscured that these “universal” collections were built through colonial violence and cultural property theft.

Specific Controversial Acquisitions:

Rosetta Stone (British Museum, acquired 1802): Taken from French forces in Egypt, itself extracted from Egypt without Egyptian input

Parthenon Marbles/Elgin Marbles (British Museum, acquired 1816): Removed from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin while Greece was under Ottoman rule—Greece has requested return for decades

Benin Bronzes (distributed across Western museums, looted 1897): Thousands of bronze sculptures stolen during British military attack—Germany began returning these in 2022, but British Museum retains large collection

Bust of Nefertiti (Berlin Museums, acquired 1913): Egyptian queen’s bust, acquired under questionable circumstances, Egypt requests return

These colonial origins remain museums’ most painful legacy, fueling current repatriation debates.

Museum Specialization and Typology

As museums proliferated, they specialized into distinct categories:

Art Museums: Focused on aesthetic appreciation, separating artwork from historical/religious context. Emphasized universal beauty and artistic genius. Examples: National Gallery (London), Uffizi (Florence), Alte Pinakothek (Munich).

Natural History Museums: Displayed specimens organized by Darwinian evolutionary principles. Created elaborate dioramas showing animals in “natural” habitats. Combined education with entertainment. Examples: Natural History Museum (London), American Museum of Natural History (New York).

Science and Technology Museums: Celebrated industrial progress and scientific discovery. Featured working models, interactive demonstrations, technological innovations. Examples: Science Museum (London), Deutsches Museum (Munich).

History Museums: Presented national narratives through artifacts, documents, and historical recreations. Emphasized patriotic stories and foundational myths. Examples: Germanisches Nationalmuseum (Nuremberg), Musée de l’Histoire de France (Versailles).

Archaeological Museums: Displayed ancient civilizations’ material culture. Often focused on Classical (Greek/Roman) or Near Eastern (Egyptian, Mesopotamian) antiquities. Examples: Pergamon Museum (Berlin), Egyptian Museum (Cairo).

This specialization reflected professionalization—museums required expertise in specific fields rather than generalist knowledge. It also reflected 19th-century disciplinary formation: art history, archaeology, anthropology, natural history became distinct academic fields, and museums followed suit.

The American Museum Movement: A Different Model (1870s-1920s)

While European museums emerged from royal collections transitioning to public ownership, American museums developed differently—reflecting American democratic ideals, capitalist philanthropy, and distinctive cultural anxieties.

American Exceptionalism in Museums

The United States lacked the aristocratic and royal collections that seeded European museums. American museums had to be built from scratch, leading to a distinctive model:

Private Philanthropy, Not State Funding: Major American museums were founded by wealthy industrialists, not government. This reflected American ideology favoring private initiative over state action, but also concentrated cultural power in wealthy hands.

Civic Group Foundations: Museums typically originated with civic organizations—wealthy citizens forming associations to establish cultural institutions. Boards of trustees (drawn from social and economic elite) governed museums, maintaining control over mission and acquisitions.

Democratic Rhetoric Mixed with Elite Reality: American museums proclaimed democratic missions—”art for the people,” “education for all”—while being funded and controlled by industrial magnates. This tension between egalitarian rhetoric and plutocratic reality characterized American museums.

Practical Orientation: American museums emphasized utility and education over aesthetic contemplation. Influenced by pragmatic philosophy and progressive education, American museums developed extensive programming, labels, and outreach—more accessible than European temples to high culture.

Major American Museums Founded (1870s-1890s)

The Gilded Age (1870s-1900) saw extraordinary wealth concentration among industrialists—Rockefeller (oil), Carnegie (steel), Morgan (finance), Frick (steel and coal). These “robber barons” funded cultural institutions to establish legitimacy, social prestige, and civic responsibility.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1870): Founded by New York’s cultural elite, the Met aspired to rival European museums. Lacking inherited collections, it purchased extensively on the art market. From inception, the Met declared its purpose was “encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts, and the application of arts to manufacture and practical life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and to that end, of furnishing popular instruction.”

This democratic mission coexisted with governance by wealthy trustees whose tastes shaped acquisitions. The Met became America’s preeminent art museum, with encyclopedic collections spanning global cultures and historical periods.

Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, 1870): Boston’s Brahmin class—old money families descended from colonial merchants—founded the MFA to assert cultural leadership. The museum emphasized education, offering lectures, publications, and study programs. It also pursued non-Western art earlier than many American museums, building strong Japanese and Chinese collections.

Philadelphia Museum of Art (1876): Emerging from Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition, this museum embodied American industrial optimism. The exhibition showcased American manufacturing and technological progress; the museum was created to preserve that legacy and provide design education for manufacturers.

Art Institute of Chicago (1879): Chicago’s nouveau riche industrial elite founded the Art Institute to prove Midwestern cultural sophistication. The museum combined art exhibition with practical education—operating an art school training designers and craftspeople. This integration of fine art and applied arts reflected American pragmatism.

Detroit Institute of Arts (1885): An industrial city’s cultural aspirations, the DIA aimed to provide working-class access to art. Its mission explicitly emphasized serving diverse audiences, not just elite patrons. This populist orientation distinguished it from East Coast institutions.

American Museums vs. European Models

Several key differences emerged:

Governance Structure:

- American: Private boards, non-profit corporations

- European: Government ministries, national/municipal authorities

Funding Sources:

- American: Endowments, donations, fundraising, admissions (historically)

- European: Government budgets, stable state funding

Collection Building:

- American: Purchased from art market, donations from collectors

- European: Inherited royal collections, archaeological finds from colonial territories

Mission Emphasis:

- American: Democratic education, practical application, accessibility

- European: National grandeur, cultural preservation, aesthetic contemplation

Accessibility:

- American: Often charged admission (until late 20th century shifts)

- European: More commonly free (though restricted access persisted)

Architecture:

- American: Mix of monumental and accessible styles

- European: Predominantly neoclassical temples

Implications: The American model’s reliance on private funding created vulnerability to donor influence but also flexibility. Museums could pursue innovative programming without government bureaucracy but needed constant fundraising. This model spread globally in the late 20th century as government arts funding declined.

The American approach also democratized taste-making—collecting decisions reflected wealthy patrons’ preferences rather than royal courts or government ministries. Whether this represented genuine democratization or merely different elite control remains debated.

20th Century: Professionalization, Democratization, and Critique (1900-2000)

The 1900s transformed museums from 19th-century nationalist monuments into professionalized educational institutions—while also subjecting them to unprecedented critical scrutiny about whose stories they tell and who they serve.

Museums as Professional Institutions

Curatorial Profession Emerges: The early 20th century saw curatorship become a recognized profession requiring specialized education. University programs in art history, archaeology, and museum studies trained professionals. Curators needed academic credentials—PhDs became common—rather than simply being wealthy collectors or generalists.

This professionalization brought systematic approaches to acquisition, documentation, conservation, and interpretation. It also created professional hierarchies and sometimes distanced museums from communities they served.

Conservation Science: Museums developed scientific conservation methods. Climate control, chemical analysis, restoration techniques, and preventive care became standard. This ensured long-term preservation but also increased operational costs.

Education Departments: Dedicated museum education staff created programming for schools and public audiences. Guided tours, lectures, hands-on workshops, and published materials made collections more accessible. Education became recognized as core museum function, not afterthought.

Museum Associations and Standards: Professional organizations like the American Alliance of Museums (AAM, founded 1906) and International Council of Museums (ICOM, founded 1946) established ethical standards, best practices, and professional development. ICOM’s museum definition evolved from 1946 (“collections open to public of artistic, technical, scientific, historical, and archaeological material”) to 2022 (institutions “in service of society” that “foster diversity, operate ethically with participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing”), reflecting changing understanding of museums’ role.

Democratization Beyond Physical Access

Early “public” museums remained socially exclusive despite free admission. True democratization required addressing multiple barriers:

Economic Accessibility: Free admission movements removed monetary barriers, though many museums retained entrance fees through the mid-20th century. The shift toward free or pay-what-you-wish admission reflected belief that culture should be accessible regardless of economic status.

Temporal Accessibility: Extended evening and weekend hours accommodated working people who couldn’t visit during weekday daytime. This simple change dramatically expanded who could actually access museums.

Interpretive Accessibility: Museums developed clear explanatory labels, audio guides, and educational materials. Rather than assuming visitors possessed art historical or scientific knowledge, museums began explaining context and significance.

Cultural Accessibility: Beyond physical access, museums worked to create welcoming atmospheres. This meant confronting intimidating formality, class-based gatekeeping, and cultural assumptions about who “belongs” in museums.

Children’s Museums: Dedicated spaces for young learners emerged, recognizing children learn differently than adults. Interactive exhibits, hands-on activities, and playful environments made museums child-friendly.

Outreach Programs: Museums brought programming to communities that couldn’t easily visit—lending exhibitions, mobile museums, school partnerships, community programs.

Museums and War

World Wars profoundly affected museums:

World War I: Museums became propaganda tools, mounting exhibitions supporting war efforts. Collections faced danger from bombing (though WWI destruction was limited compared to WWII). The war also disrupted international cooperation and triggered nationalism that affected museum missions.

World War II: The Nazi regime looted art systematically from Jewish collectors and occupied territories. Museums evacuated collections to countryside hiding places for protection. After the war, restitution efforts attempted to return stolen art—a process continuing today with Holocaust-looted art claims.

WWII also transformed museum content—Holocaust museums emerged as new institution type, using collections to bear witness and educate about genocide.

Cold War: Museums became sites of ideological competition. The U.S. and Soviet Union used cultural diplomacy—touring exhibitions, artistic exchange programs—to demonstrate cultural superiority. Museums received government support not just for education but for propaganda.

This reveals museums aren’t neutral but caught in political conflicts, serving national interests even while claiming universal values.

Critical Museum Studies and Decolonization

Beginning in the 1960s-70s, scholars began questioning museum authority and challenging dominant narratives:

New Museology Movement: Critics argued museums shouldn’t be authoritative temples dictating truth but forums for dialogue. The “new museology” emphasized:

- Community participation in curation and interpretation

- Multiple perspectives rather than single authoritative narrative

- Social relevance and activism rather than detached preservation

- Questioning power dynamics embedded in collecting and display

Postcolonial Critique: Scholars from formerly colonized regions challenged Western museums’ colonial foundations:

- Whose objects are displayed? (Often stolen from colonized peoples)

- Whose stories are told? (Often colonizer perspectives, not Indigenous voices)

- Who benefits? (Western audiences consuming “exotic” cultures)

- What’s missing? (Stories of colonial violence, Indigenous agency)

Feminist Critique: Feminist scholars revealed museums’ gender biases:

- Art museums overwhelmingly featured male artists

- Women artists undervalued in acquisitions and exhibitions

- Female subjects objectified in artwork presentation

- Museum leadership and curatorial staff predominantly male

Repatriation Movements Begin: Indigenous communities and source nations began demanding return of cultural objects and human remains. The U.S. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990) required federally funded institutions to return Native American remains and sacred objects to tribes. This established legal framework for repatriation, inspiring similar movements globally.

Blockbuster Culture and Architectural Spectacle

Late 20th-century museums embraced blockbuster exhibitions and spectacular architecture:

Blockbuster Exhibitions: The 1970s King Tutankhamun exhibition drew unprecedented crowds and revenue. Museums learned that major temporary exhibitions attracted masses and generated income. This created economic pressure to pursue popular shows, sometimes at expense of collection research and permanent exhibition quality.

Starchitect Buildings: Museums commissioned famous architects to design landmark buildings. Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao (1997) exemplified this trend—the building itself became the attraction, drawing tourism and regenerating a declining industrial city. This “Bilbao Effect” inspired cities worldwide to commission spectacular museum architecture.

Critics worried architecture overshadowed art, and tourism overwhelmed educational mission. Proponents argued dramatic architecture attracted audiences who might otherwise never visit museums.

21st Century Museums: Digital, Diverse, and Debating Their Role (2000-Present)

Current museum transformations directly affect how we experience museums today. Digital technology, decolonization movements, and social justice activism are reshaping institutions in real-time.

The Digital Revolution

Online Collections: Museums are digitizing collections for online access. Google Arts & Culture partners with institutions worldwide, providing high-resolution images and virtual tours. Museum databases make research collections searchable. This democratizes access—anyone with internet can view works once requiring international travel.

Virtual Tours and Experiences: COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021) forced museums to close physically, accelerating digital experimentation. Institutions offered virtual tours, online programs, live-streamed events, and digital-only exhibitions. When physical locations reopened, many maintained hybrid programming.

Statistics reveal impact: during 2020 lockdowns, the Louvre’s website received 10.5 million visits (vs. 9.6 million physical visitors in 2019). While some engagement was temporary, digital access permanently expanded.

Social Media Engagement: Museums use Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and Facebook for education and community building. Social media enables direct dialogue, behind-the-scenes content, and viral reach. This creates opportunities (engaging younger audiences, informal learning) and challenges (pressure to create “Instagram-worthy” exhibitions, simplifying complex topics).

Digital-First Museums: Some new museums exist primarily or entirely online, without physical buildings. This radically reduces costs and enables global access but loses the physical object encounter that defines traditional museums.

Opportunities and Limitations:

Opportunities:

- Global accessibility transcending geography

- Preservation through digital backup

- New storytelling methods (interactive, multimedia)

- Searchable research collections

- Education at scale

Limitations:

- Digital divide excludes those without technology/internet

- Screen fatigue and diminishing attention

- Loss of physical encounter with objects (scale, materiality, aura)

- Technical obsolescence (formats become unreadable)

- Lack of tactile, spatial, social museum experience

The question isn’t whether digital replaces physical but how museums balance both, using digital to enhance rather than replace embodied experience.

Decolonization and Repatriation Debates

Museum colonial legacy has become central issue, with high-profile repatriation cases generating international attention.

Major Recent Cases:

Benin Bronzes: Germany announced in 2021 it would return Benin Bronzes looted by British forces in 1897. Transfers began in 2022, with thousands of objects returning to Nigeria. This represents significant decolonization progress.

However, British Museum still holds large Benin collection and resists return, citing legal restrictions and “universal museum” mission.

Machu Picchu Artifacts: Yale University held artifacts removed from Machu Picchu by explorer Hiram Bingham in 1911. After lengthy negotiations, Yale returned the materials to Peru (2011), but debates continue about whether complete restitution occurred.

Egyptian Mummies and Artifacts: Egypt requests return of major pieces, including the Rosetta Stone and Nefertiti bust. Museums resist, arguing objects are better preserved and accessible in European institutions—arguments Egypt rejects as paternalistic colonialism.

Arguments FOR Repatriation:

Cultural Property Rights: Objects were stolen during colonialism and belong to origin communities. Legal ownership doesn’t erase moral obligation.

Self-Determination: Communities should control their own cultural heritage, deciding how it’s preserved and displayed.

Healing Colonial Wounds: Returning objects acknowledges historical injustice and supports reconciliation.

Local Context: Objects have deeper meaning in origin communities where they’re understood culturally, not just aesthetically.

Capacity Building: Source countries develop strong museums; arguments about “better preservation” in the West are outdated and racist.

Arguments AGAINST (Universal Museum Concept):

Global Heritage: Major museums serve humanity by making diverse cultures’ achievements accessible to global audiences.

Research Access: Encyclopedic museums enable comparative study across cultures, advancing scholarship.

Preservation: Some source countries lack resources for proper conservation (though this argument increasingly rejected as patronizing).

Legal Ownership: Museums acquired objects legally under period laws; retroactive claims are inappropriate.

Arbitrary Timelines: If returning colonial-era acquisitions, why not all cross-cultural transfers throughout history?

Compromises and Alternatives:

Shared Stewardship: Origin communities and museums jointly govern objects, making decisions collaboratively.

Rotating Exhibitions: Objects spend time in both origin location and international museums.

Digital Repatriation: High-quality digital replicas and documentation shared with source communities when physical return isn’t feasible.

Cultural Exchange: Museums build reciprocal relationships, not extractive collecting.

These debates will shape museums for decades, forcing institutions to confront how colonial violence built their collections.

Museums and Social Justice

Black Lives Matter protests (2020) prompted museums to examine their own racism and exclusion.

Addressing Historical Racism:

Museums acknowledged complicity in racist systems:

- Collections underrepresented artists of color

- Interpretive materials ignored racial violence

- Staffing lacked diversity, especially in leadership

- Audiences skewed wealthy and white

Responses included:

- Diversifying acquisitions and exhibitions

- Rewriting labels to acknowledge slavery, segregation, colonialism

- Diversifying staff through targeted hiring

- Community advisory boards including marginalized voices

- Free admission and programming in underserved neighborhoods

Decolonizing Gallery Labels:

Museums began rewriting interpretive materials:

- Acknowledging objects acquired through colonial violence

- Including Indigenous perspectives on cultural items

- Noting contested ownership and repatriation requests

- Explaining historical context of racism, imperialism, exploitation

This represents significant shift from neutral-sounding labels that erased power dynamics and violence.

Museums as Activist Spaces:

Debate emerged: Should museums take political positions or remain neutral?

Activist position argues:

- Neutrality is impossible—museums always reflect values

- Claiming neutrality supports status quo

- Museums should actively work for social justice

- Public institutions have obligations to marginalized communities

Neutrality position argues:

- Museums preserve and educate, not advocate

- Political activism divides audiences

- Funders and governments may punish politically active museums

- Museums lose credibility if seen as partisan

This tension continues unresolved, varying by institution.

Accessibility and Inclusion Initiatives

Beyond physical access, museums work toward genuine inclusivity:

Physical Accessibility:

- Wheelchair access, ramps, elevators (now legally required)

- Accessible bathrooms and facilities

- Assisted listening devices

- Large-print and Braille labels

Sensory Accessibility:

- Touch tours for blind/low-vision visitors

- Sensory-friendly programs for neurodivergent visitors

- Quiet hours with reduced stimulation

- Sensory maps indicating potentially overwhelming spaces

Economic Accessibility:

- Free admission days

- Pay-what-you-wish policies

- Reduced-price memberships for low-income families

- Free school partnerships

Intellectual Accessibility:

- Plain language labels avoiding jargon

- Multilingual materials

- Multiple interpretation levels (basic, intermediate, advanced)

- Family-friendly programming

Cultural Accessibility:

- Diversifying collections and exhibitions

- Hiring diverse staff

- Community curation and programming

- Addressing whose stories are told and how

These initiatives recognize “public” means actively welcoming everyone, not just opening doors and hoping people enter.

Contemporary Challenges and Debates

Museums face complex challenges:

Funding Crises: Government arts funding declined in many countries. Museums rely increasingly on private donors, corporate sponsorship, and earned income. This creates vulnerability—wealthy donors influence programming, corporate sponsors seek favorable publicity, commercial pressure shapes exhibitions.

Ethical Donor Questions: Should museums accept money from problematic sources? Recent debates involved:

- Sackler family (opioid crisis) → Many institutions removed Sackler name

- Fossil fuel companies → Climate activists object

- Tech billionaires → Questions about labor practices, monopoly power

- Authoritarian regimes → Concerns about “reputation laundering”

Climate Change: Museums face contradiction: climate-controlled storage requires enormous energy, but museums should address climate crisis. Some museums installing solar power, reducing energy use, and mounting climate-focused exhibitions.

Misinformation Era: As public trust in institutions declines, museums position themselves as reliable information sources. But some audiences reject institutional authority, creating challenges for science museums especially.

Measuring Success: Should museums measure success by attendance, revenue, social media engagement? Or by educational impact, community relationships, social change? Metrics shape priorities, and overemphasis on numbers can undermine mission.

Future Role: Museums face identity questions: Entertainment destinations? Educational institutions? Community centers? Social services providers? Activist organizations? Different stakeholders envision different futures.

Case Studies: Institutions That Embody Transformation

Examining specific museums in depth reveals how abstract historical forces played out concretely.

The Louvre: From Royal Palace to Revolutionary Symbol to Global Icon

Before (pre-1793): The Louvre was a fortified palace built in 1190, rebuilt as a Renaissance residence in the 1500s. French kings accumulated art collections, particularly Louis XIV who amassed paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts. These remained royal property, accessible only to court.

Transition (1793): Revolutionary government nationalized royal property, declaring the Louvre would become Musée Français. On August 10, 1793, the museum opened to public for free—revolutionary in both senses. The act symbolized the people’s victory, with former royal treasures now belonging to all citizens.

The National Convention declared: “The French Republic, by assembling these masterpieces in this magnificent palace, makes evident its power and its wealth; no longer is France subjugated.”

Evolution: Napoleon dramatically expanded collections through military conquest, looting masterpieces from Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Egypt. After Napoleon’s defeat, some works returned to origin countries, but much remained.

The Louvre became model for national museums worldwide. Throughout the 19th-20th centuries, collections grew through purchases, donations, and archaeological expeditions.

Current Status: The Louvre is the world’s most visited museum (9.6 million visitors in 2019, pre-pandemic). Major expansions included I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid (1989) and satellite Louvre-Lens (2012). The controversial Louvre Abu Dhabi (2017) franchise raised questions about commercializing national museums.

What It Reveals: The Louvre’s evolution shows museums as political tools—revolutionary symbol, imperial showcase, tourist destination, commercial brand. The journey from “property of the French people” to global franchise reveals tensions between national patrimony and international engagement, public mission and commercial imperatives.

British Museum: Cabinet of Curiosities to Universal Museum

Before: Hans Sloane’s private collection—71,000+ natural specimens, books, manuscripts, antiquities—assembled through his career as physician and naturalist. Typical cabinet of curiosities mixing disciplines.

Transition (1753): Sloane bequeathed collection to nation for £20,000. Parliament accepted, passing British Museum Act establishing institution by government action rather than private initiative.

Evolution: The 19th century transformed the British Museum through colonial expansion:

- Egyptian antiquities from Napoleonic Wars and archaeological expeditions

- Parthenon Sculptures removed by Lord Elgin

- Assyrian materials from Mesopotamian excavations

- Asian art from trade and colonial administration

- Benin Bronzes looted in 1897 military action

By 1900, the British Museum epitomized the “universal museum”—encyclopedic collections spanning human history and global cultures.

Current Position: The British Museum vigorously defends “universal museum” concept against repatriation demands. Former director Neil MacGregor promoted the museum as serving “worldwide civic purpose,” arguing collections should remain in London for global audiences.

Critics counter that this maintains colonial patterns, prioritizing Western access over origin communities’ rights to their cultural property.

What It Reveals: The British Museum embodies museum colonial legacy. Its transformation from Sloane’s eclectic cabinet to global encyclopedia occurred through imperial expansion. Today’s repatriation debates force reckoning with that history.

The “universal museum” concept—presented as benevolent internationalism—can be read alternatively as justifying continued possession of colonially-acquired objects.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: American Democratic Ideal Through Private Wealth

Before: Unlike European museums evolving from royal collections, the Met was created from nothing by civic association. New York cultural leaders decided the city needed a major art museum and organized to create one.

Creation (1870): Founding statement declared purpose was making art accessible for education and “application of arts to manufacture and practical life”—characteristically American emphasis on utility.

Wealthy patrons funded acquisitions, purchasing from European art market rather than inheriting collections. This meant building collections rapidly through strategic buying.

Evolution: Major donors shaped collections through gifts and bequests:

- J.P. Morgan: decorative arts, medieval objects

- Benjamin Altman: paintings and sculpture

- Robert Lehman: paintings, drawings, decorative arts

The Met became America’s premier art museum with encyclopedic scope rivaling European institutions—achieved in 150 years versus centuries.

Current Challenges: The Met exemplifies American museum model’s contradictions: democratic rhetoric (“art for everyone”) alongside plutocratic reality (wealthy trustees shaping mission). Recent controversies included:

- Pay-what-you-wish admission debates (some saw required suggested donation as discriminatory)

- Donor influence over exhibitions

- Deaccessioning policies (selling works to fund operations vs. acquisitions)

- Repatriation demands for objects with problematic provenance

What It Reveals: The Met demonstrates American exceptionalism in museums—private philanthropy creating public institutions. This model enabled rapid collection building and programming innovation but also concentrated cultural power in wealthy hands.

The ongoing tension between public access mission and donor dependence shapes American museums broadly.

Why Museum Evolution Matters Today

Understanding museum history isn’t just antiquarian interest—it illuminates current debates and visitor experiences.

The “Public” Question Remains Unresolved

Museums are legally public, but who actually visits?

Studies consistently show museum audiences skew:

- Higher income (middle and upper class overrepresented)

- Higher education (college-educated dominate)

- White (people of color underrepresented, varies by city)

- Older (youth, especially teens, scarce except school groups)

Physical access doesn’t guarantee cultural access. Many people feel museums “aren’t for them”—seeing institutions as elite spaces where they don’t belong.

Current efforts to address this include:

- Free admission to remove economic barriers

- Culturally relevant programming

- Diverse staff reflecting communities served

- Accessible marketing and outreach

- Creating welcoming environments

But structural barriers persist. Museum hours favor those with flexible schedules. Locations often require car ownership. Cultural content assumes background knowledge. These aren’t accidents but legacies of museums designed for elite audiences.

Power and Authority in Museums

Museums wield significant power through decisions about:

What’s Valuable: Acquisition decisions determine what’s preserved for future generations. Art market prices follow museum validation. Cultures and artists museums ignore remain undervalued.

Whose Stories Get Told: Exhibition choices determine which histories become public narratives. Marginalized communities’ stories often remain untold, making their experiences invisible.

Who Interprets Objects: Curators traditionally possessed interpretive authority—their explanations became “truth.” Community curation and multiple perspectives challenge this, but museums still largely control narratives.

Who Benefits: Museums employ staff, educate audiences, support scholarship, boost tourism. But who receives these benefits? Communities from which collections originated often excluded.

Museums are reconsidering authority through:

- Community advisory boards

- Co-curation with Indigenous communities and source cultures

- Multiple interpretive voices (not single authoritative label)

- Acknowledging contested perspectives and ongoing debates

Colonial Legacy and Global Justice

18th-19th century imperial expansion built major museum collections. This remains deeply problematic:

Acquisition Circumstances: Many objects were stolen during colonial conquest, acquired through unequal power dynamics, or removed without meaningful consent. Legal ownership doesn’t erase moral questions.

Whose Heritage: Museums hold cultural property from communities worldwide, often possessing more Indigenous artifacts than Indigenous communities themselves possess. This represents ongoing colonialism—controlling others’ cultural heritage.

Interpretive Authority: Western museums long interpreted non-Western objects through colonial lenses, emphasizing “exoticism” or “primitivism” rather than presenting Indigenous perspectives.

Ethical Obligations: What do museums owe communities from which collections originated? Return? Compensation? Collaboration? Acknowledgment? No consensus exists.

Repatriation and decolonization will define museums for decades. Some institutions embrace this as moral imperative; others resist, fearing collection dissolution and mission compromise.

Digital Transformation’s Double Edge

Digital access democratizes in some ways while creating new inequalities:

Opportunities:

- Anyone with internet can view collections globally

- Preservation through digital backup protects against loss

- Searchable databases enable unprecedented research

- Virtual exhibitions serve remote audiences

- Education reaches beyond physical visitors

Risks:

- Digital divide: those without technology/internet excluded

- Physical experience loss: scale, materiality, atmosphere irreplaceable

- Screen fatigue: another online experience amid saturation

- Technical challenges: obsolescence, maintenance costs

- Superficial engagement: clicking through images differs from contemplative museum visit

The question isn’t digital vs. physical but how museums thoughtfully integrate both, using digital tools to enhance rather than replace embodied museum experience.

The Future of Museums: Predictions and Possibilities

Where are museums heading? Based on current trends and historical trajectory, we can identify likely developments, optimistic possibilities, and pessimistic concerns.

Likely Developments (5-10 Years)

Hybrid Physical-Digital Experiences Become Standard: Museums will integrate digital technology throughout physical spaces—AR overlays providing additional information, personalized audio guides adapting to interests, interactive displays connecting physical objects with digital content. Virtual visits will remain available, serving those unable to attend physically.

Increased Repatriation and Collaborative Curation: Pressure will intensify for returning colonial-era acquisitions. More museums will adopt collaborative models—working with origin communities on interpretation, management, and ownership rather than unilateral museum control. Expect major institutions to return high-profile objects, though complete repatriation unlikely.

Museums as Community Centers: Beyond exhibitions, museums will expand services—hosting community meetings, offering social services, providing mental health resources, serving as civic forums. This reflects recognition that museums’ value extends beyond collections to community building.

Sustainability Focus: Climate change concerns will push museums toward environmental responsibility—renewable energy, reduced climate control where feasible, sustainable operations. Museums will also mount more exhibitions addressing climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and environmental justice.

AI and AR Integration: Artificial intelligence will personalize visitor experiences—recommending objects based on interests, answering questions, generating customized tours. Augmented reality will visualize lost contexts—showing sculptures in original temple settings, reconstructing damaged artifacts, animating historical scenes.

Optimistic Possibilities

Museums Leading Social Justice Efforts: Museums could become leaders in truth-telling about historical injustice, supporting marginalized communities, and advocating for equity. Using collections to illuminate systemic racism, colonialism, and inequality, museums could help society reckon with difficult pasts.

Global Collaboration Replacing Competition: Rather than competing to hoard objects, museums could collaborate globally—sharing collections through long-term loans, jointly curating exhibitions, supporting museum development in Global South. Encyclopedic museums could evolve from possession to partnership.

True Democratization: Museums could achieve genuine inclusion—representing all communities, making all feel welcome, dismantling barriers that exclude. Free admission, accessible programming, diverse leadership, and community control would transform museums into genuinely public institutions.

Preservation of At-Risk Heritage: Museums could focus on preserving cultural heritage threatened by climate change, conflict, and development. Digital documentation, strategic acquisition from at-risk sites, and support for in-situ preservation could protect what might otherwise be lost.

Pessimistic Concerns

Funding Crises Force Closures or Corporate Control: Declining government support could force museum closures, especially smaller institutions. Surviving museums might become increasingly corporatized—sponsored exhibitions, naming-rights sales, commercial programming prioritizing revenue over mission.

Digital Replaces Physical: If museums over-invest in digital at physical expense, they risk losing core identity. Why maintain expensive buildings and collections if digital equivalents serve more people? This logic could lead to collection sales and building closures—devastating for irreplaceable objects.

Museums as Entertainment Venues: Blockbuster mentality could dominate, with museums competing for audiences through spectacular temporary shows, celebrity collaborations, and “Instagram moments” rather than serious engagement with collections and ideas.

Continued Exclusion Despite Rhetoric: Museums might embrace inclusion language without substantive change—diversity statements replacing actual diversification, land acknowledgments without repatriation, access programs without addressing structural barriers.

Unanswered Questions

Can Museums Be Both Popular and Serious? Can museums attract mass audiences while maintaining educational depth? Or must they choose between accessibility and rigor?

How to Balance Preservation with Access? Every visit, every touch risks damage. Climate control consumes energy. How do museums balance preservation for future generations with current access?

What’s Museums’ Role in Divided Societies? Can museums build common ground in polarized times? Or do attempts at inclusivity alienate some while insufficiently satisfying others?

Will Museums Remain Relevant? In an age of infinite digital content, why do physical museums matter? What do they offer that can’t be replicated online?

These questions lack clear answers, but addressing them thoughtfully will determine museums’ future relevance and impact.

Common Questions About Museum Evolution

What is the origin of museums?